Country-specific materials- a Brazilian case study

Virginia Garcia, Ricardo Sili, Carla Chaves, Cultura Inglesa, Brazil

Menu

Main aims

Curriculum development

Market research

The approach

The syllabus

Why country-specific materials?

References

The project described in this article was originally set up by the Cultura Inglesa Rio de Janeiro - Brasília in 2001 with a view to creating a collection of country-specific materials which would meet the needs, wants and expectations of the Brazilian learner. In the article, we discuss the different elements of the project with a view to establishing the values, principles and beliefs we based the development of the teaching materials on, as well as the aims to be achieved.

Main aims

At its origin, the Cultura Inglesa Rio de Janeiro-Brasília materials development project had two main aims:

1. To respond to the particular needs of the Brazilian learner by taking advantage of the fact that the institution the materials were developed for had close to 100% monolingual and monocultural students in class.

2. To provide the teacher, teaching in a Brazilian context, with a set of materials she would not have to keep adapting or changing in an attempt to make the teaching-learning process more adequate to the learner's needs and reality.

Curriculum development

Following a reconstructionist approach to curriculum development (Clark, 1987:14), the project had as a starting point an initial research of learners 'wants and expectations', i.e., a bottom-up process for collecting data to be used as the input for curriculum development.

Before going any further, it is worth digressing a little to make a distinction between the terms 'wants and expectations' and the term 'needs' as they are used in this paper. By 'wants and expectations', we are referring to those aspects which are perceived as desirable in a service or in a product, i.e., the attributes which would influence the customer's decision to buy a service or a product.

On the one hand, 'wants and expectations' are interpreted as needs which are felt by the customer in an objective way and that can be expressed by them easily. On the other, by 'needs', we mean the final result of a judicious interpretation of experts of the 'wants and expectations' mentioned above; in Clark's (1987:36) terms, 'things done in the best interests of the pupils'.

Since the development of the curriculum was originally conducted with a view to meeting the needs of the Brazilian learner, or of learners living in a Brazilian environment, the fact that the members of the team directly involved in the project were Brazilians themselves can only be considered as an important asset. For one thing, the curriculum developers shared the same cultural background with the target user of the material. For another, being native-speakers of Brazilian Portuguese, they themselves had been through the process of learning English as a foreign language. Therefore, they found themselves in a favourable position to anticipate difficulties and could offer learners alternatives to overcome them. Needless to say, the project developers were in a position to make suggestions of alternative ways in which the learning process could be optimised.

All in all, the aspects above were used as the basis upon which the curriculum was founded and they supported the team in the setting of criteria for the definition of the approach and the design of the syllabus.

Market research

A process of researching the market preceded the kick-off of the project. In short, the result of the research indicated that Brazilian learners are motivated to learn English in order to:

1. express themselves orally, i.e. to speak the language;

2. understand what they hear comfortably;

3. operate in social situations, as a priority.

When asked to name what they considered more important to learn to achieve their goal, subjects indicated the importance of a good range of vocabulary as the most important element in the process of learning English. The second most important aspect concerned pronunciation. When analysing the results it is clear that subjects aim at a level of comfortable intelligibility in Kenworthy's terms (1989: 3). To our surprise, the need to learn grammar came as third. Above all, learners in Brazil expect the process of learning English to take place "quickly".

When interpreted, the 'wants and expectations' detected by the research established pedagogical needs which influenced directly the curriculum development as mentioned above. For example, the development of speaking and listening skills would have to be prioritised over reading and writing. The importance of the teaching of lexis and pronunciation was par with that of grammar. In other words, the curriculum was based on 'goals relevant to the communicative needs of the learner' (Trim, 1978).

The approach

One of the first decisions made was to follow a principled approach, i.e., the curriculum developers were not to favour a single approach or method but instead would borrow ideas in a principled way from a range of teaching methods and approaches. Therefore a process of critical analysis of existing approaches and methods was necessary in order to establish a framework for action. The results of this process indicated key principles which had their roots mainly in the Communicative Approach to Language Teaching and in the Lexical Approach. It is true that a few techniques were borrowed from the Audio-lingual Method.

The main key principles can be summarized as follows:

Language is a means of communication. The majority of activities proposed in the material aim at promoting interaction and are designed 'to focus on completing tasks that are mediated through language or involve negotiation of information and information sharing' (Richards & Rogers,1986:76). The value of facilitating learner interaction is stressed throughout the materials and it is one of our main aims. The concern with providing learners with 'probable rather than possible English' (Lewis, 1997:15) permeates the material from the very beginning although some 'EFLese' could not be totally avoided in very early stages.

Learning does not take place in a linear way. A systematic process of recycling underlies the material with a view to guaranteeing the constant recurrence of certain language items and features. As Tomlinson (1998:15) writes 'Research into the acquisition of language shows that it is gradual rather than instantaneous process…Acquisition results from the gradual and dynamic process of internal generalisation rather than from instant adjustments to the learners internal grammar.' A whirlpool approach was established for the materials with a view to helping learners to internalise the target language at a dynamic and lively pace. Among other things this approach avoids tedious unnecessary repetition that may increase the learners' level of anxiety and shake his/her self-confidence which could eventually affect his rate and pace of learning (Dulay, Burt and Krashen, 1982).

The four skills need to be developed. The development of oral and listening skills was prioritised as a direct response to our learner's wants and expectations. However, reading and writing skills are needs which can be clearly related to the learner's professional requirements. We believe that as part of the process of language learning to provide the learner with materials which are important and relevant to his/her needs, wants and expectations helps whoever is producing the materials to achieve a perception of relevance and utility in the materials. It suffices to say that the four skills are dealt with within the material in different proportions (Refer to Syllabus Rationale section below).

Learning is a cognitive process. Materials development should maximise learning potential by encouraging the intellectual involvement of learners in activities which stimulate both right and left sides of the brain (Tomlinson, 1995:20). Activities and tasks proposed in the materials aim at making use of learners' previous experience and their brains.

The sound use of L1 is a powerful teaching/learning tool. As speakers of Brazilian Portuguese, the team of authors is aware of the language system features of learner's L1 which gives them the possibility to make L1 an ally to enhance learning. Therefore activities involving L1 and L2 comparison and translation are to be found in the material (Lewis, 1997). The use of L1 as a means of instruction happens especially at earlier stages with a view to offering learners affective support and enhancing their self-confidence.

Vocabulary is the major tool to carry meaning. Since we are in a privileged situation of creating materials to be used with groups of monolingual students, i.e., Brazilian Portuguese speakers, the materials expose learners to a significant quantity of vocabulary which include (true and false) cognates and deal with meaningful chunks most of the time (Lewis,1997).

Learners need to have motivation and develop a sense of achievement from the very beginning.In order to nurture strong and consistent motivation and a positive feeling towards the process of learning, learners need before anything else to be exposed to roughly-tuned input, in Krashen's terms i+1 (1985) . According to Krashen, each learner will only learn from the new input what s/he is ready to learn. The material can aid the teacher to achieve readiness by creating situations which require 'the use of variational features' (Tomlinson, 1995).

Similarly, the materials should cater for a comfortable and relaxed atmosphere which would make learners feel at ease and confident, ready to learn within an anxiety-free environment. Materials which contain activities which are useful to the learner, relevant to their needs and within their capability may ensure motivation and foster a sense of achievement.

Last but not least, consistent but not exaggerated practice is provided in the materials vis-à-vis the development of a sense of achievement on the learners' part. Activities ranging from more controlled to less controlled meaningful practice can be found in the materials.

The syllabus was designed so as to respond more accurately to the Brazilian learner's profile in terms of their perceived needs, specific linguistic difficulties and strengths, general knowledge and cultural background.

The syllabus rationale was the result of a careful consideration of internal elements, like the learners' wants and needs, and institutional values and beliefs, as well as of external elements, such as international examinations' syllabi and specifications.

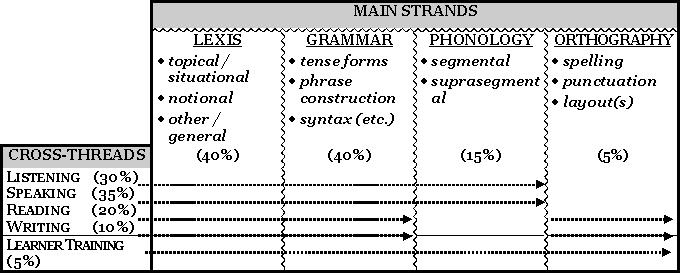

In the table below, the percentages indicated are general in the sense that they reflect an overall balance across the syllabus as a whole. Also, the strands and weightings may vary as learners progress. The development of the four skills and a learner training programme function as cross-threads permeating the main strands. i.e., language aspects were dealt with at the same time as skills were developed. Good integration of strands and cross-threads, plus well-written materials and activities, should produce the 'discourse strand'.

The syllabus

Choices in designing the syllabus

The choice of contents for the specific syllabuses - i.e., list of lexical items, grammar topics and phonological elements - was also directly influenced by the Brazilian learner's profile, as well as the choice of topics used in the material.

->LEXIS

The list of vocabulary items put together was selected so as to reflect the needs, interests, and reality of the prospective learners. Also, the fact that Brazilian Portuguese and English share a lot of true cognates allowed the list of lexical items to include words that are usually considered advanced for this level, but which would present no difficulty for the Brazilian learner. A positive consequence of the inclusion of such words is the unique opportunity it gives the learners to build up their lexical repertoire more quickly, which was very much in tune with their expectations.

->PHONOLOGY

The list of phonological aspects to be dealt with in the material contains only those segmental and suprasegmental elements that are especially difficult for the Brazilian learner to master, and that might affect their comfortable intelligibility (Kenworthy, 1989: 3). For example, Brazilian learners tend to confuse the phonemes /r/ and /h/ in initial positions, so special emphasis is given to the contrast between them. By the same token, there is no focus at all on the production or contrast between the phonemes /b/ and /v/, as they do not represent a problem for Brazilian Portuguese speakers.

->GRAMMAR

Different emphasis was put on some grammatical areas rather than on others, based on the level of difficulty they might present to the target learner. The criteria used to decide that was the degree of similarity or difference between English and Brazilian Portuguese as to the form, concept and use of each particular item.

For example, Brazilian Portuguese has verb tenses which are basically the same as the present and past continuous in English, sharing with them both form and concept (though the use of the present continuous with future reference is more restricted in Brazilian Portuguese). So these two English verb tenses could be dealt with more lightly and faster than usually done in international course books, as Brazilian learners can grasp their concept and form much more easily than, for instance, speakers of German or French.

On the other hand, it is usually quite hard for Brazilian learners to use 'there be' correctly, because Brazilian Portuguese expresses this concept in a totally different way from English. Therefore a differentiated approach was used when presenting and practising it, so as to provide the learner with activities that were appropriate to the specific sort of difficulty they usually face.

->TOPICS

The common cultural background shared by the prospective users of the materials - learners and teachers - allowed the team of authors to count on a wide range of topics on which to base texts for presentation of language and skills development that might be impossible in materials designed for a multicultural market. Humour, for example, was one of the elements used constantly in the development of the materials.

Why country-specific materials?

The reason we set out to develop country-specific, intercultural materials was the strong belief we shared that by responding to the specific needs, wants and expectations of the (Brazilian) learner, we would facilitate the process of learning, and hopefully make it more effective.

In 2003, we published our first set of materials, a series for adult learners called Interlink. Since then two other series have been released, Flash and Action. Many others are in the pipeline. In 2002, Learning Factory, a Brazilian publishing house whose main goal is to develop country-specific intercultural teaching materials, was established. For three years in a row, we have been conducting surveys with teachers and learners who are using Learning Factory materials to find out their level of satisfaction. The positive results we have been obtaining come to show that the development of country-specific materials, i.e., materials developed for monolingual and monocultural learners, enable users to:

-> activate background knowledge of their world helping them to build intercultural and cross-linguistic bridges with the target language and cultures;

-> learn within a comfortable and anxiety-free atmosphere supporting them to achieve their goal, i.e., to learn English.

Country-specific materials can foster motivation in learners since they mirror their linguistic and cultural needs, yet at the same time they establish a fruitful and productive connection between cultures and languages. We hope that that will help learners strike a happy medium between internal and external learning climate and promote effective learning.

References

Clark, J. L. 1987. Curriculum Renewal in Foreign Language Learning. Oxford: OUP.

Dulay, H., M. Burt and S. Krashen. 1982. Language Two. New York: OUP.

Kenworthy, J. 1989. Teaching English Pronunciation. Harlow: Longman.

Krashen, S.. 1985. The Input Hypothesis. London: Longman.

Lewis, M. 1997. Implementing the Lexical Approach. Hove: Language Teaching Publications.

Richards, J. & Rodgers, T. 1986. Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge: CUP.

Trim, J. L. M. 1978. Some Possible Lines of Development of an Overall Structure for a European Unit-Credit Scheme for Foreign Language Learning by Adults . Strassbourg: Council of Europe.

Tomlinson, B. (edited), 1995. Materials Development in Language Teaching. Cambridge: CUP.

|