Editorial

The music is available from http://onegreenleaf.podomatic.com/

The credits for the recording are:

Music and Lyrics: Renata Suzuki

Vocals: Renata, Masa and Cherish

Percussion: Greg Chako and Masa

Arranged and recorded by Michael Fogarty 14.02.2007at Infiniti Studios

The music is free as in a creative commons arrangement.

T is for Tiger: Eco-consciousness Raising and Patterns of Violence

Renata Suzuki, Japan

Renata is an Economics ESP teacher at Sophia University, Tokyo. Current interests are environmental and peace education, learner autonomy and CALL, particularly using blogs for professional development. She has published a book of free EFL ecosongs for kids at www.onegreenleaf.net, among others. The presented ideas come from Columbia Peace Education Certificate Learning Unit Outline (TC Tokyo Peace Education Certificate Fall 2007). E-mail: renate@zaa.att.ne.jp

Menu

Personal note and background

Social Purpose

Rationale: Finke ( 2001)

Procedure

References

I graduated from the Columbia Peace Education Certificate Program this

January, and this is my final learning unit. I aimed at teaching

English with young children, and including the free song I wrote and

recorded in February 2007. I would like to share it with other teachers.

This learning unit will help children to question their “natural entitlement” to exploit animals for their body parts, raising consciousness of the unrecognized violence we perpetrate against members of our planet. This conscientization makes the invisible, the given, visible: that within the gendered structure of our society, we feel we can use and abuse animals without thought, to meet any human needs or desires, however frivolous. It rephrases the relation between humans and animals as a planetary family, establishing bonds of sympathy and interdependence with mother tiger, brother rhino and baby whale. It invites children to notice or imagine alternative ways to meet various human needs that do not harm animals. It further offers children a model of speaking out as a means of protection for the vulnerable, lifting their concerns from patriarchal silence and anonymity into the consciousness of the inclusive planetary group.

Reardon (1997) has described the parameters of a culture of peace in human and social terms: ‘A culture of peace…would be based upon the diversities of different cultures and appreciation of ‘the other’, meaning complete refusal of dominance, exploitation and discrimination in all human relations and social structures” (p.25). While Reardon’s words could hardly ring more true, I would broaden her definition beyond human relations and social structures to include the concept of eco-culture, or how we can exist as one among many animals sharing a biosphere. Indeed, Reardon herself has defined human security based on four basic pillars: a sustainable environment, food, clothes and shelter, human dignity based on human rights and protection from avoidable harm. Human security is therefore indivisible from environmental security. According to Article 16 of the Declaration of Human Rights from a Gender Perspective:

All women and men have the right to a sustainable environment and level of development adequate for their well-being and dignity. All women and men have the right to access technologies sensitive to biological diversity, essential ecological processes and life conservation systems in industry, agriculture, fishing and pasturing.” (p.4)

Reardon calls for a fundamental shift in societal priorities toward complexity of thinking and a nuanced long-term approach, working from the perspective of the vulnerable, thinking in universal and global terms, and a sense of human solidarity and responsibility for all. These beliefs are all concomitant with a sustainable holistic eco-model of peaceful planetary existence. In terms of the shift in thinking this implies, Bowers (1993) quoting Leopold is exemplary: “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise” (1970, p.262).

According to Finke (2001), since ecological violence is also based in a patriarchal worldview, we must indeed explore the problematique of gender and violence in order to heal with our planet:

“It is our individual and social prejudices, our economic and economical (or simply habitual) ideologies, in short: it is our cultural ecosystems which produce our unified and uniform landscapes and destroy the wealth of our natural ecosystems. What has become questionable is precisely our cultural identity…This means that in our political and extra-political action for the reform of our scientific, economic and other behaviour against nature we need experts on man/woman and his/her inner landscapes, besides the experts on the outer landscapes, on technologies, on plants or animals.” (p.89)

If issues of ecological sustainability are interwoven with issues of patriarchy, gender and violence, then together with our children, we must begin to develop new ways of celebrating the voices and diversity on our planet and move away from a destructive and limiting androcentric worldview and language. In the words of Berman (2001), “…it is necessary to creatively employ new metaphors and idioms to represent Nature and our relationship with the natural world. There is also a great need to create a positive semantic space for marginalized peoples, other beings and natural systems.” (p. 267). This learning unit offers songs and activities to begin exploring a new way of thinking about the animals (including ourselves) on our planet.

To an increasing extent, politics will have to deal with those [environmental] problems. But as is evident today, the classical strategies of a non-sustainable politics of economical power fall short of the necessities of fundamental reforms of our habits and life-styles…As far as nature conservation is concerned, I think it is a mistake to believe that technical experts and natural scientists, especially experts of the diverse biological sciences, are the appropriate or the only experts in this field…in order to protect or even restore the stability and richness of our natural ecosystems, one has to analyse, to influence and change our cultural ecosystems which are responsible for their damage. That is to say, the problems of the environment are problems of the consciousness of our self and its role, rather than problems of nature itself. (p.89)

Young children grow up unaware of the underlying prejudice and ideologies of elders. This learning unit will help young children to see the hidden exploitation of animals, to hear their silenced voices in our planetary society and confront the misery an androcentric world creates. In a peace education tradition, giving voice to the vulnerable (in this case animals) is suggested as a way to overcome violence. The unit facilitates celebrating planetary diversity, exploring from an eco-perspective and transcending an exploitative patriarchal view of animals. It hopes to facilitate peaceful planetary awareness, suggesting we can transcend a gendered society by ‘doing eco-human’. It thus seeks to preempt exploitation and ‘othering’ of humans, animals and ecosystems born of misunderstanding, ignorance and fear.

Children working with this unit will begin to understand ecological problems are related to every human being, and that the gendered problematique of our violent relationship with nature is not only relevant to all of us, but one which we can personally and actively transform: “…Our experiences of the natural world are socially and culturally constructed. Our language plays a significant role in constructing these experiences, our reality and therefore our actions. As such, the way we conceive of Nature and portray Nature through our language has serious implications for our relationship with the natural world and with each other. (my italics)…”(Berman, 2001:p.267)

“Regardless of the origins, it is clear that within patriarchal culture male hierarchy is maintained through cultural dichotomies which legitimate the logic of domination…. Both women and Nature become objects for man's use…(A)as prostitutes we become sex-objects and in the natural world animals are meat, experimental objects or prisoners in a freak show, while plants, trees and minerals become dollars. This objectification stems from the internalization of hierarchy and dualistic assumptions prevalent in Western society. Many ecofeminists argue then, that the creation of hierarchy and the process dualism provides an intellectual basis for the domination of women and Nature.” (Berman, 2001:pp. 260-261)

Women in particular have long borne the brunt of “moral exclusion” (Opotow, 2000) in our society, and so has nature. Both spheres are subject to the same basic problematique. Opotow states that “Moral exclusion…views those excluded as outside the community in which norms apply, and therefore as expendable, undeserving and eligible targets of exploitation, aggression and violence.” (p.417). Many researchers have noted the way violent actions are white-washed linguistically and morally, with strategies Berman refers to as “absent referent” (2001, p. 264). Kahn (2001) refers to a strategy of ‘masking the unpleasant or unethical’:

‘test animals which are ‘housed’, ‘dosed’ and ‘processed’-rather like an innocuous manufacturing process…coyote ‘control’ has replaced the more distasteful (and accurate) coyote killing; mammals are now clamped by their legs for capture or death in ‘Soft-Catches’, padded steel traps; and ‘nuisance animals’ (i.e. those whose behavior has been found offensive to humans overtaking their habitat) are ‘relocated’ or ‘translocated’ rather than banished from their territories and social groups-usually after being darted, drugged, caged and hauled by their bellies from a helicopter. (p.243)

Exploring voices in this learning unit, students grow in an awareness and freedom of expression which moves toward being inclusive of all sentient beings.

Audience: groups of EFL K-3 learners

Educational Goal: The instructor will offer songs and learning exercises that will provide participants with approaches to conceptualizing power (lessness), re-affirming the need to minimize violence and giving voice to the vulnerable with a sense of appreciation and unity. The lesson aims to prepare students to manifest their own ecological human dignity and to respect and defend that of other planetary beings.

Learning Objectives: Students will:

- recognize the importance of protecting animals and sharing them with a safe and secure planetary environment

- understand that animals are the victims of cruel treatment and abuse and are taken advantage of in our present system or way of life.

- Realize that we are all sentient beings with rights to life and to grow in diversity on the planet

- Know that speaking out and giving voice to concerns is a way to initiate change in people’s lifestyles and habits while still meeting human needs

Knowledge: English vocabulary concerning animals and their characteristics. Knowledge of how we use and kill animals for their body parts, and how some are in danger of extinction. Knowledge of how it feels to be vulnerable.

Skills: Linguistic skills: how to spell words and alphabet awareness, personal and plural pronouns for individuals and groups (I, we), development of vocabulary: animal nouns and adjectives; discourse patterns of ordering and requesting (Do/ Don’t/ Please). Socio-cultural skills: Ability to empathize with weaker parties and give voice to their feelings. Interpersonal skills: Ability to work in large and small groups in peer learning situations. Meta-cognitive skills: Reflecting on learning and silent Meditation.

Values: A sense of shared planet, empathy and relation with all living beings and the joy of ecological diversity. Giving voice to hidden problems and developing peaceful, non-oppressive ways of living.

Time required to complete the unit: Flexible, depending on time available and student interest (see each section for approximate times)

Core Concepts: One eco-family, Animal Rights, Speaking out, Diversity, Unity

Materials:

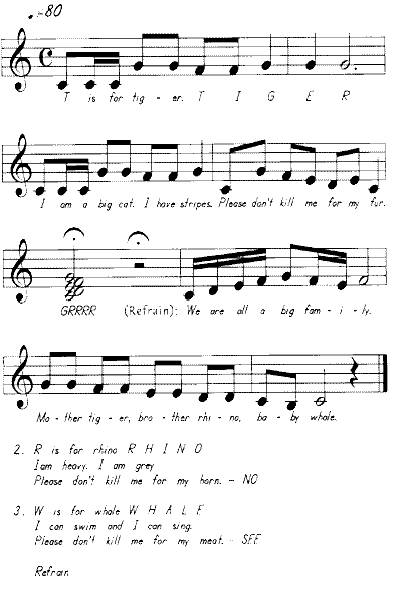

A: Song: Renata Suzuki (1996) One Green Leaf: 10 Earth Songs for Kids

http://homepage.mac.com/deibuyagi/renata/pages/tiger.html

T is for Tiger

B: Drawings/Realia to pass round for an animal quiz (or use the photos below)

|

What's it made of? |

|

Passing round various items for the kids to touch and feel and guess: what's it made of? Animals help us make many beautiful things in our lives, can you guess which one helps us make these beautiful knits? |

|

This is a close up of a Japanese woven Nishijin obi, the sash used to wrap round kimonos. It almost looks like embroidery, very luxurious...and all the beautiful colors. What's it made of? Guess the animal. |

|

Above a sneak peek to help you guess. |

|

Traditional Instruments like the Japanese koto, use ivory to prop up the silk strings and tune the instrument, and in the finger mounted picks...plastic can be used, but the sound is slightly different, according to experts. Now you can guess the animal who makes the music possible, can't you? The Japanese guitar (shamisen) is vibrating animal hide (cat or dog) stretched over a frame, and the large hand held pick (bachi) is also often made of solid ivory, as the following site will tell you www.inv.co.jp/~shammy/indexE.html |

|

Inden

is a traditional Japanese leather industry made for the samurai armour...the lacquerwork is stencilled onto the leather...and what's it made of? |

|

Handbag, belt, shoes, fashion items we take so much for granted...what are they made of? |

|

now then, what lovely fur is this? |

|

|

C: Teacher Processing and Facilitating Questions:

Which animals are still alive to stroke and cuddle? What do the animals say? How can we respect them and still have pretty bags and coats and scarves? The answers to the quiz are: woollen sweaters: sheep/ alive kimono threads: silk worms/ dead...ivory is elephant teeth, very often elephants are poached and killed for their tusks, the Inden shoes and wallets are made of deer skin/ dead and the handbag is cow leather, also dead...my cat is called Peasuke, and he is handsome and alive, miaouw...stroke and cuddle :)

All photographs originals by Renata Suzuki http://onegreenleafecosongs.blogspot.com/2005/10/t-is-for-tigerminiquiz.html

D: Waterpistol, Music Player and T is for Tiger music

Methods: Singing and Dancing, Quiz, Personal Sharing, Brainstorming in dyads, Meditation

Teaching Procedures and Learning Sequence:

- Greetings: Teacher welcomes students. Tell students we are going to work with a song and play the song once or twice, and continuously as BGM throughout the lesson.

- Animal Quiz: Guess the animal: Teacher puts up pictures (see Materials B) or hands out objects one by one and students guess the animal it is made of. If students have difficulty, give three alternative animal hints to choose from with picture prompts (10 mins)

- Reflective Question/ Discussion: Gather children round to discuss what all the animals have in common (they are dead). See materials C. (5 mins)

- Musical Statues: Ask children how it feels to be killed. With a water pistol, play T is for TIGER and when the music stops students must freeze or be shot. Take turns to be it and shoot. Students can avoid their “fate” if they put hands up and shout “Please don’t shoot me”. (10 mins)

- Reflective Question/ Discussion: In turn and using mother tongue, children share their feelings about being threatened and threatening others. This sharing is very important to help students explore feelings and the teacher should be very sensitive to support possible stress and discomfort with the experience. Ask if animals have a voice to ask not to be shot, and how we can give a voice to animals. Ask if we have alternative ways of meeting needs for sweaters and scarves, shoes and food that do not harm animals.(10-15 mins)

- Giving voice to the Animals: Ask students to pair up with a partner. Give students pictures of endangered or exploited animals. Pairs should spend time thinking of the answer to the

question:

- What do you like about being a tiger?

- What do you like about being a rhino?

- What do you like about being a whale?

- What do you like about being a shark?

- What do you like about being a deer?

Teacher as facilitator circles, helping students who may also work with a mother tongue, to expand language: I like being big/free/ yellow etc. I like eating fish/ I like running/ I like catching food/ I like sleeping/ I like lazing in the sun etc. etc.

Then each pair stands up and presents their picture and report. After each presentation the teacher models “I’m happy to be me. Please don’t shoot me”. (Adapted from Goodman & Schapiro, 1997, pp. 113-14) Collect the student phrases and language to add in the song.

- Everyone sings T is for Tiger, each verse adding language from the student presentations. This song has a kind of Indian tom-tom beat, so you can have the kids thump sticks on the floor and click stones together in a tum-ta-ta tum-ta-ta rhythm to give it an ethnic feel. If you want to produce the song for a small culture event have each child be an animal and stand up between verses to speak a message to humans.

- Alternative to 6: Spelling bee with alphabet cards: children choose an animal and have a race to lay out cards and make the word, or racing to the board to write them. Otherwise teacher can put whale-rhino-tiger-horn-meat-fur-mother-brother-baby-family in an abc square for the kids to find and circle, or make a crossword or invite students to make a crossword online:

www.awesomeclipartforkids.com/crossword/crosswordpuzzlemaker.html

- Candle Light Meditation: Children sit silently in a circle breathing deeply, looking at a candle in the centre as teacher leads a simple guided meditation to finish the learning with an inner sense of peace: Reach out and cup the candle light in your hands. Feel the candle glow in your hands, and slowly bring your hands to your forehead, to share the light in your head. Next touch your eyes, so that they will see the light in all things, your ears, so that you hear good, warm words, and your mouth, so that you speak with kind warm loving. Now bring the light to your heart, and feel it flow down from there to your tummy, and bum, and all the way down your legs and knees to your toes. Feel the warm candle glow in your feet and toes…all of you is orange and warm and glowing with light and peace. Now spread out your glow, so we are all a network of orange warm light together, peace in the room. Now we’re radiating peace out to the planet and all the animals on the planet, the whole world filled with warm light. Remember, I am in the light, the light is in me, I am the light. (5 mins)

Adapted from Burrows (1991)

Berman, T. (2001). The Rape of Mother Nature? Women in the Language of Environmental Discourse. In A. Fill, & P. Muhlhausler (Eds.), The ecolinguistics reader: Language, ecology and the environment (pp. 258-69). London and New York: Continuum

Bowers, C.A. (1993). Critical essays on education, modernity, and the recovery of the ecological imperative. New York, Teachers College Press.

Burrows, L. (1991). Light Meditation. In Sathya Sai Education in Human Values Lesson Plans Group 1 Part 2 (p.17). Sathya Sai Foundation of Thailand.

Finke, P. (2001). Identity and manifoldness: New perspectives in science, language and politics. In A. Fill, & P. Muhlhausler (Eds.), The ecolinguistics reader: Language, ecology and the environment (pp. 84-90). London & New York: Continuum.

Goodman, D. & Schapiro, S. (1997). Sexism curriculum design. In M. Adams, L.A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (pp. 110-40). London & New York, Routledge.

Kahn, M. (2001). The passive voice of science: Language abuse in the wildlife profession. In A. Fill, & P. Muhlhausler (Eds.), The ecolinguistics reader: Language, ecology and the environment (pp. 241-44). London & New York: Continuum.

Jenkins, T., & Reardon, B. A. (2007). Gender and peace: Towards an gender inclusive, holistic perspective. In C.P. Webel, & J. Galtung (Eds.), Handbook of Peace and Conflict Studies (pp. ). New York: Routledge.

Leopold, A. (1970). A Sand County almanac. San Francisco, CA: Ballantine.

Opotow, S. (2000). Aggression and violence. In M. Deutsch, & P.T. Coleman (Eds.), The handbook of conflict resolution: Theory and practice (pp.403-427). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Reardon, B. Toward human security: A gender approach to demilitarization.

Reardon, B. (1997). Diagnosing intolerance and describing tolerance. In Tolerance: Threshold of Peace, Unit 1. UNESCO, Paris.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the What’s New in Language Teaching course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching through Art and Music course at Pilgrims website.

|