Coping with Sociopragmatic Failure: Suggested Activities

Sezgi Sarac-Suzer, Turkey

Dr. Sezgi Sarac-Suzer earned her PhD degree in teaching English as a foreign language at Hacettepe University, Turkey. She holds a BA and MA in the same area of focus. She has worked as an English teacher in Turkey, taught Turkish as a foreign language in the United States and worked as a Research Assistant at Hacettepe University, Turkey. Now, she works as a lecturer at the ELT department of Baskent University in Ankara, Turkey. Her research interests are teacher knowledge, syllabus design, pragmatics and material development.

E-mail:sezgi.yalin@emu.edu.tr

Menu

Introduction and Background

Problem

Aim and Method

Suggested Activities

Activity 1: Scale of Politeness

Activity 2: Who are the Speakers?

Activity 3: A Poem of Euphemism

Conclusion

References

Learning English in a non-English speaking community is a much more challenging endeavor than in an English speaking environment. As a foreign language learner, you devote a lot of time to learn the foreign language in the classroom setting. You master grammar and vocabulary with the implementation and guidance provided by your class teacher. Each and every lesson, you answer comprehension questions, fill in the blanks, match the words in columns, find and correct the mistakes. But when it is time to interact with foreigners whose language has been your area of focus for so long, you feel stuck!

The related literature (Takahashi and Beebe, 1993, Blum-Kulka and House, 1989, Leech, 1983; Thomas, 1983) emphasizes that linguistic and lexical knowledge is not enough to be competent in using a foreign language. Both pragmatic and sociopragmatic considerations come into play and constitute the important features of using a language effectively and of achieving mutual intelligibility. In language use, the pragmatic failures can be caused by inappropriate use of linguistic forms and they can be considered relatively easier to overcome via language instruction methodologies.

On the other hand, the latter, sociopragmatics, refers to “the social conditions placed on language in use” (Thomas, 1983, p. 99). Harlow (1990, p. 328) provides a distinctive feature of sociopragmatics, which is the interdependent relation between linguistic forms and sociocultural contexts. It is the knowledge on how to vary the language output in speech acts according to different situations and/or social considerations. ‘Saying sorry’, as an example of speech act, has different variations, such as, ‘I am so sorry,’ ‘I apologize,’ ‘I beg your pardon,’ ‘excuse me.’ These expressions constitute the pragmatic aspect of language use, and the awareness of -when to use what- is the sociopragmatic aspect. The sociopragmatic competence is the speaker’s adjustment of speech strategies according to social variables and the context (Harlow, 1990; Fraser, 1990). The main areas of failure are specifically as speech act realizations and also vocabulary selection depending on sociocultural concerns.

Low level of sociopragmatic competence causes failure in intelligibility. Besides, the speaker fails to perform the action and/or utterances required by the speech-act situation, such as apologizing, making an offer, saying thanks. Unfortunately, it is not possible to identify and single out only one source as the cause of sociopragmatic failure. The most probable reasons might be limited knowledge on the relevant social and cultural values and not to know how to vary speech strategies in cross-cultural communication (Harlow, 1990; Kasper, 1997; Thomas, 1983). Sociocultural factors such as differences between the first and the target language cultures can mislead the learners in language productions and interpretations. The deficiency in the knowledge of the target culture norms contributes to failure.

In terms of sociopragmatic failure, the effect of mother tongue might be interpreted differently. One might argue that first language (L1) interferes and becomes the source of problem; however, as proposed by Newmark (1966) there is the other side of the coin. When non-native speaker does not know how to express herself in the foreign language (FL), she refers to her mother tongue and compensates the unknown in FL with a similar expression in L1. The mother tongue is not the reason of the failure but it works as a source of reference when needed. All languages have sociolinguistically related regulations but the problem is that they do not overlap all the time, some of them do vary. These differences form the basis of sociolinguistic failure. These failures are witnessed especially in the speech act realizations and vocabulary choice by foreign language users. Teachers then must be acquainted with sociopragmatic qualities of language use and adapt language teaching goals accordingly.

In this study, I aimed to suggest activities to raise foreign language learners’ awareness on sociopragmatic language use. In the design of activities, my point of reference was the data gathered from my students learning English as a foreign language. I had interviews with the students who had contact with native speakers abroad or in Turkey, and they shared what type of difficulties they faced in daily life speaking. In their narrations, both pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic difficulties were highlighted. After this small scale data collection procedure on failure in speech act realizations and vocabulary choice, I decided to develop in-class activities on teaching sociopragmatic language use. I applied the suggested activities in the course ‘Contextual Grammar I’ for the first year students studying at Hacettepe University, department of English Language Teaching. This application was an opportunity to evaluate the design of activities and to do necessary changes to turn them into more effective ones to be used in class.

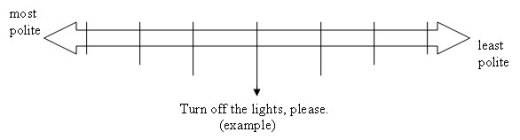

The teacher draws a scale of politeness on the white board. On one side of the continuum, the degree of ‘most polite’ is indicated; on the other side the ‘least polite’ is located and one sentence is given on the scale to set an example. The scale might be as follows:

Later, the participants are given some strips of sentences and asked to find the most appropriate point to place these sentences on the scale. While working on this activity, learners discuss the speaker’s intention, and try to decide on the sociopragmatic value of the language use. The sentences provided in the activity are as follows:

Move your chairs towards the wall.

Would you mind if I opened the window?

Sorry. Could you tell me the way to Brighton Street, please?

Would it be all right if I took this chair, please?

Turn off the lights, please.

Hey Andy, lend me 10 dollars, will you?

Would you mind if I took this chair, please?

Take this table into the house.

I am sorry to bother you but could you possibly help me please?

Mary! Hurry up and get the phone.

The sentences are context-free. As the second stage of the activity, the teacher asks learners to speculate about the context by identifying who might be the speakers, their age, social status and also the setting in which the expressions are used. This in-class discussion elaborates the variables playing an important role in the selection of expressions and elements which determine the degree of politeness. The material for this activity might be as follows:

As a follow up activity, the teacher asks the participants to identify the linguistic features which determine the level of politeness. Especially the comparison of the least and most polite expressions and their related intention-determining parts of speech provide a practical linguistic analysis for the students. The identification of difference making language usages is a short-cut to understand how to turn a command to a request by using lexical and linguistic means. The teacher’s role for these activities is facilitator; also s/he acts as a guide and source person.

Learners are presented an adapted dialogue from the play Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller (cited in Barnet, et.al, 1993, pp.1042, 1073). However, learners are not provided with any data related with the characters, theme or setting of the play. They just see the characters’ names preceding the speech lines, which provide data on the interlocutors’ gender. Right after reading the first extract, they start to speculate on the speakers’ age, social status, and their possible degree of relationship. They do an in-depth analysis of speakers’ intentions while reading between the lines. While doing these, they firstly get familiar with everyday expressions in the language and also get used to the deviant nature of slang. Later, the teacher provides the information on characters so that learners can compare their predictions with the content of the play. The selected section from the play and suggested material to be used for the activity are as follows:

A.

Willy: Wonderful coffee. Meal in itself.

Linda: Can I make you some eggs?

Willy: No. Take a breath.

Linda: You look so rested, dear.

Willy: I slept like a dead one. First time in months. Imagine, sleeping till ten on a Tuesday morning.

….

Linda: Willy, dear I got a new kind of American-type cheese today. It’s whipped.

Willy: Why do you get American when I like Swiss?

Linda: I just thought you’ like a change…

Willy: I don’t want a change! I want Swiss cheese. Why am I always being contradicted?

Linda: I thought it would be a surprise.

Willy: Why don’t you open a window in here, for God’s sake?

Linda: They’re all open, dear.

|

Age |

Social Status |

Character |

Setting (place and time) |

Their degree of relationship |

| Linda |

|

|

|

|

|

| Willy |

|

|

|

As the second stage of the activity, learners are asked to rewrite the dialogue. But this time, they are supposed to create a shift in the speakers’ intentions such as changing the ‘rude’ language of a character to a polite one or making the ‘polite’ character sound more ‘rude’ and/or ‘indifferent’. Later, learners share their dialogues and discuss what kinds of language use make the difference. While sharing the new dialogue, depending on the learners’ attitude, the teacher might ask them to role play their new dialogue.

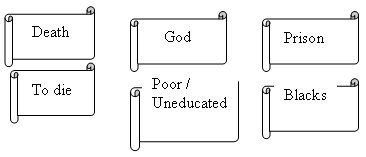

This time learners focus on euphemism which is an aspect of sociopragmatics in terms of vocabulary selection. Poetry is a great source of language presentation and practice on connotative meaning. The teacher firstly groups the students and gives a list of vocabulary on different slips of paper. She or he asks the students try to figure out how to express the words in an indirect or less offensive way and they organize the given vocabulary in a different table with their own suggestions of euphemisms. The selected vocabulary and provided table are as follows:

| Words: |

Indirect / Less Offensive Equivalences: |

| Death |

|

| God |

|

| Prison |

|

| To die |

|

| Poor / Uneducated |

|

| Blacks |

|

Later, the teacher gives the poem below and asks the students to match the words with the expressions used in the poem. Learners read and discuss the poem in groups while trying to find out the euphemisms used instead of the words given in the list. The poem is:

|

Answers |

| People of color, |

(Blacks) |

| People of all faiths, |

|

| Are invited to be a part of |

|

|

|

| Correction facilities. |

(Prisons) |

| Who will the first comers be? |

|

| The ill-advised, |

(Poor/Uneducated) |

| Those whose protector |

(God) |

| Has long been passed away, |

(Die) |

| Those whose end is near, |

(Death) |

| In society. |

|

| Arıkan, A. (2006) |

As a follow up activity, teacher gives another set of words and euphemisms and asks learners to create a poem by bringing together as many euphemisms as possible. Learners work in groups again and try to combine euphemisms in a content of a poem. As one group’s poem will be different from another, in the post stage, learners share their productions with the whole class. The suggested list of vocabulary and euphemism is:

- senior citizen – old person

- low-enforcement officer – policeman

- undertaker – a person or firm whose job is to dispose of the bodies of people who have died

- visually impaired – blind person

- substance abuser – a drug addict

- to downsize – to reduce the size and wages bill of a company by sacking employees

(Shoebottom, 2001)

The central concern of the suggested activities is that in the realization of communicative acts, non-native speakers of English have difficulties, and sociopragmatic concerns play an important role in this. Recent studies highlight the importance and necessity of using effective in-class applications in this area (Yu, 2006; Eslami-Rasekh, 2005; Crandall and Basturkmen, 2004; Bardovi-Harlig and Griffin, 2005). Meaning and form need to be practiced together in relation with the culture of target language. These activities on sociopragmatics aim to join these two ends by enabling awareness and more intelligible language productions by students. Further research and in-class application samples on sociopragmatics are needed to improve learners’ communicative skills and sociopragmatic competence. A collection of activities organized around different speech-acts might provide practitioners with a data base of various applications and a source of inspiration to create their own personal materials.

Arıkan, A. (2006). Personal poems. Unpublished manuscript.

Bardovi-Harlig, K. and Griffin, R. (2005). L2 pragmatic awareness: Evidence from the ESL classroom. System. Vol:33. 401-415.

Barnet, S., Berman, M., Burto, W. (Eds.) (1993). An introduction to literature: Fiction, poetry, drama. New York: HarperCollings College Publishers.

Blum-Kulka, S. ve House, J. (1989). Cross-cultural and situational variation in requestive behavior in five languages. In S. Blum-Kulka, J. House, & G. Kasper (Eds.), Cross-Cultural Pragmatics (pp.123-154) Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Crandall, E. and Basturkmen, H. (2004). Evaluating pragmatics-focused materials. ELT Journal. Vol: 58/1. 38-49.

Eslami-Rasekh, Z. (2005). Raising the pragmatic awareness of language learners. ELT Journal. Vol: 59/3, 199-208.

Fraser, B. (1990). Perspectives of politeness. Journal of Pragmatics, 14, 219-236.

Harlow, L. L. (1990). Do they mean what they say? Sociopragmatic competence and second language learners. The Modern Language Journal, 74, 328-351.

Kasper, G. (1997). Can pragmatic competence be taught? Second language teaching & curriculum center. University of Hawaii. Alıntı: 17.03.2004.

www.hawaii.edu/Net Works/

Leech, G. (1983). Principles of pragmatics. London: Longman.

Newmark, L. (1966). How not to interfere with language learning. Language Learning: The Individual and the Process. International Journal of American Linguistics. 40: 77-83.

Shoebottom, P. (2001). Euphemisms: A guide to learn English . Retrieved September 12 2006 from

esl.fis.edu/parents/easy/euphem.htm

Takahashi, S., & Beebe, L. M. (1993). Cross-linguistic influence in the speech act of correction. In G. Kasper & S. Blum-Kulka (Eds.), Interlanguage pragmatics (sf. 138-157). New York: Oxford University Press.

Thomas, J. (1983). Cross-cultural pragmatics failure. Applied Linguistics, 4, 91-112.

Yu, M. (2006). On the teaching and learning of L2 sociolinguistic competence in classroom settings. Asian EFL Journal. 8 (2).

www.asian-efl-journal.com/June_06_mcy.php

Please check the British Life, Language and Culture course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English for Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|