Lessons on Song and Culture

Alma Daniela Otero S. and T. Nevin Siders V., Mexico

Daniela Otero holds a Master’s in Higher Education from the Universidad Intercontinental and is a teacher at the Foreign Language Centre in Mexico’s National University of Education Sciences (UPN). She is a member of the team that designed and is pioneering the UPN’s online postgraduate course (especialización) in teaching English (EEAILE). Daniela also volunteers for the Mexico City chapter of MEXTESOL. e-mail: danielaotero@yahoo.com.mx

Nevin Siders is department chair in the B.A. in Adult Education at the UPN. He holds an M.A. in Applied Linguistics from Mexico’s National University (UNAM) where his dissertation was on prosody, and a B.A. in Education from The Ohio State University, U.S.A. He also collaborates in the EEAILE. e-mail: tnevin@upn.mx

Menu

Introduction

Rationale and the learning cycle

Learning cycle

First sample for children

Second sample for children

An example for adults

Conclusion

References

This article offers a rationale for using song in classroom tasks to learn a foreign language. Authentic songs can be a springboard toward dealing with the contemporary and cultural issues established in Mexico’s public school curriculum. These tasks are designed to inspire creativity via self-expression while learning the conventions of English.

The learning cycle aims for student attention to be on new lexis and cultural aspects while carrying the tasks out, such that integration into previously-learned language is a largely unconscious process up until the focus stage at the end, per Willis (1998). For instance, intonation and rhythm are crucial for listeners to comprehend English, because the native-speaker rhythm slurs together whole syllables where almost all unstressed vowels collapse into the schwa, and we show in the examples how students focus on this toward the end of the lesson.

The first issue to address ourselves with is what culture is and how to deal with it in the classroom. Student background, preferences, beliefs and learning styles are important issues to be taken into account when planning cultural awareness within a language lesson.

Culture, language and syntax are central to songs, so songs straightforwardly lend themselves to pedagogical use. Many songs reflect aspects central to the culture in which they reside, while their popularity reflects that culture and its values and priorities in its conscious and unconscious manifestations. Conscious manifestations instantiate the symbols and images authors select for their lyrics, while unconscious manifestations reflect the syntax and order in which these metaphors and allegories are presented. These conscious and unconscious manifestations can lead toward language awareness of cultural issues by studying, practicing and discussing songs learned for specific purposes.

This is the rationale behind Mexico’s Secretary of Public Education’s (SEP) for including culture in language learning, realized through the principle of inspiring student creativity within social practices of the language (SEP, 2011: 12). Likewise, the learning of language conventions and competencies forms an integral part of the process where that product is made. Stated in more precise pedagogical terms: in consonance with the principles underlying the mandatory curriculum, it is during the process of constructing their own products that students learn about the conventions of writing, pronunciation, rhythm and intonation, rhetoric and syntax of English because they compare their works-in-progress against authentic materials, most often with the very same song or story used to open the learning cycle. (Otero and García, 2012)

One of us in a recent dissertation (Siders 2011) has emphasized that, “without intention there is no communication, and without communicative intent language itself does not exist”, which is a critical component to learning a language because the most authentic of all learning materials are those students themselves create in the speech act of expressing their own ideas and feelings. The authors of this article recognize that songs are an ideal vehicle for communicating emotions, feelings, intentions and expressions of moods. (Otero and Siders, 2012)

Rhythm and intonation also play central role tithe learning of the English language in particular, because how they operate in this language differs from how they operate in most of the world’s languages. Linguists characterize English as stress-timed, unlike almost all others which are syllabo-timed. Our students speak Spanish which, like most languages, has clear diction because its rhythm is rather quick — averaging 110 beats per minute — thus almost each and every syllable falls on a beat. English, however, has a relatively slow rhythm — about 70 beats per minute — so that several syllables or even several whole words gather together into a single beat. The consequence is that a native speaker’s rhythm slurs many syllables together, resulting in virtually all of the unstressed vowels collapsing into the schwa. (Siders ibid)

Therefore these syllables uttered between the beats suffer a reduction that linguists call elision: they are spoken so softly that a listener cannot actually hear them. Although this phenomenon is entirely unconscious, native speakers do notice it on certain occasions — known as the famous “contractions”. So it is a shame that coursebooks rarely deal with intonation and rhythm, despite how crucial they are to listeners in comprehending the spoken language. (Siders 2007)

But even more important than these linguistic issues of form is the fact that intonation is the main way in which speakers take their stance in relation to the listener and to the greater world. This is to say that the tone one uses can bring listeners “up close and intimate” or push them away from a feeling of impersonal coldness or even hostility. This “taking a stance” is what linguistics calls pragmatics, and we believe that pragmatics should not be left for advanced studies of a language, but rather need to incorporated into the very earliest of lessons, precisely because communication is what is privileged and, as we said above, “without intention there is no communication”. If one’s speech is accurate and fluent yet lacking any tone, that flat tone will in and of itself alienate anyone and everyone.

All of this explains why students must use their products as vehicles for expressing their own thoughts, feelings, values, beliefs and aspirations when learning a language. Consequently, a caution is in order: the result of such an approach is that each and every product will be unpredictable because each product is a new, unique artefact which must be valued and judged as an authentic text.

The first thing to take into consideration when preparing our classes is the national curriculum’s learning cycle, which specifies six steps or stages.

Warm-up

Recycling

Lead-in

High challenge or Presentation

Low challenge or Practice

Oral and written assessment

The Warm-up gently gets the students into English by taking attendance and carrying out other duties in the target language. This is followed by the Recycling stage which activates previous knowledge and schemata appropriate to the lesson topic. This is where the teacher’s role comes to the fore, because only careful planning helps beginners and intermediates to access the appropriate language and skills among all the things they already know about the world and about the languages of Spanish and English. Activating previous knowledge and schemata translates into getting actively involved: there are few moments in the cycle of passive reception for students, and those are certainly not in these first two steps.

The third of the six steps is the Lead-in, where making a first approximation of the topic or theme of the lesson, or refreshing the topic or theme from the previous lesson. This is where new language is brought in — always contextualized. Next comes the High Challenge, also known as Presentation, where students actively conquer the new material.

The High Challenge is followed by the Low Challenge stage, or Practice, where students gain confidence in and begin to take mastery over the new material. Assessment is the final step, the one where students demonstrate mastery of the new material via a product, while also taking notice of what language has yet to be learnt.

Now that we have reviewed the SEP’s learning cycle, it is time to turn to the three lesson plans that exemplify for various ages our songs-as-culture approach. The first two examples are for preschool and elementary students, so they follow the approach and learning sequence of our country’s compulsory curriculum. The two songs for children are the central part of content-based classes where students get involved in their feelings and values through tasks, because the songs serve as a springboard to dealing with the contemporary and cultural issues indicated in the public school curriculum where topics were chosen to inspire creativity in a product through which they can express themselves. The third is for young adults and has a freer format.

The first sample lesson, designed for kindergarten, uses The Wheels on the Bus.

The Recycling step activates previous knowledge by displaying pictures of a typical city bus and asking the students to recall having taken a bus ride and to name the people involved and some of the parts of a bus. The Lead-in step links builds the previous lessons by using graphics to name still more parts, with attention on those that will be in the lyrics.

The High Challenge or Presentation brings in the tune, displayed on an intonation chart.

The first graphic represents the musical notes in first line of the song, which is sung in chorus. While the other two images include the lyrics, these are only intended for pre-reading exposure; the teacher does not draw attention to the words, but rather to miming the actions of the bus parts that are mentioned in the verses. (See SEP, 2011: 18)

In the Low Challenge or Practice the class actually sings the song in chorus with a cute YouTube video like the one at www.youtube.com/watch?v=wQGSQLcXMRA. Before the second or third repetition, the teacher pauses to draw attention to one sound several of the words —on, the, bus, all, long — have in common, the schwa /ə/.

Because this is kindergarten, the Oral Assessment focuses only on oral language so requests that small groups make a new chant, with the teacher’s aid, that uses the same melody but with lyrics on other city scenes, which they present to the rest of the class.

The second song is You’re Beautiful by James Blunt, in a class for upper elementary children, that is, 10 to 12 years of age.

Recycling step: The students were shown flashcards with different pictures that had been taught before. They had to say aloud the lexis and action verbs from that previous knowledge.

Lead-in: In groups, students have to write a little story using pictures shown in graphics that allude to things mentioned in the lyrics: an eagle, an eye, a crowd, and so on.

High Challenge or Presentation: Each of the groups receives a different set of instructions to work through this hands-on practice stage on the song You’re Beautiful. One group works with a scrambled word activity, another group has an error correction task, another works out an exercise to find the adverbs, nouns and other parts of speech. For this hand-on practice stage they have 15 to 20 minutes to work and then share with the whole class.

Low Challenge or Practice: Students were motivated to write their own songs using previous and new vocabulary which they must chose to fit into the same rhythm and intonation. The teacher points out how important it is to be creative so as to link the words and action verbs when writing a story!

Oral and Written Assessment: Once they had made their own poem or song using the lexis from Blunt’s original song, they are asked questions such as these that aim to motivate self-evaluation.

- Did the song we wrote have a realistic rhythm and intonation?

- Did the song we wrote have most of the images?

- Did the song we wrote include metaphors (i.e. vocabulary) from the original song?

The third example uses Penny Lane in a course for young adults.

When preparing this beginner’s course, the teacher had made a concordance of Beatles songs that exemplified the theme, lexis or grammar of each of the course’s units. The principal activities throughout were personalization tasks such as changing the lyrics or bringing them to life via theatre. The sample we present for this article is one of this latter kind.

The UPN’s Foreign Language Centre aims for the students to learn English or French for academic purposes, or better said for academia, since all of the institution’s degree programs are in the field of education. A believer in the extreme version of content-based language learning, the teacher leaves this aside and faces up to the challenge of assuring the appropriateness of the syllabus to the curricula of education where the students are teachers and researchers in the UPN’s learning culture that upholds and promotes social cognition and the process of living small group work becomes critical.

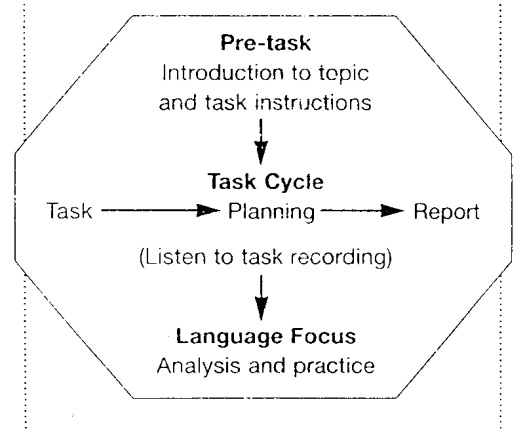

One of the most widely-accepted learning sequences designed to propitiate such a collective thought process is Willis’s task cycle, applied here to small groups. The Task-based cycle has just three steps, with the straightforward names Pre-task, Task Cycle and Language Focus.

image from Willis (1998)

The Pre-task step consists of what is otherwise known as the introduction or warm-up, where the learners access and activate their previous knowledge of the topic, often by brainstorming. The Pre-task stage is designed to accomplish at least three objectives: to motivate, to activate previous knowledge on the topic, and to set out instructions for accomplishing the task proper. It may also serve as a moment to introduce language necessary to success.

The Task Cycle step itself has three “phases” within it, (plus an optional one for listening), which collectively offer the learners a variety of contexts for exposure to the language. The first is the Task phase, where the students have opportunities for spontaneous use of the language employing whatever resources they have (including their mother tongue) to research and to prepare their presentation. They work in small groups so their attention is on the content and its message, rather than on any mistakes that may arise, which is to say that accuracy has little importance at this moment. In the Planning phase the teacher can give input and advice, including help with language, to help the students organise and prepare for the following Report phase. Thus accuracy begins to take precedence, which is why the teacher’s monitoring and advising becomes critical to success. Then in the Report segment the students make their presentations to the larger audience (the class, the school, online, etc.). The Report phase combines fluency with accuracy because, in their roles as presenters, students want both to get the message across and to do so with as few errors as possible. After all presentations have been given, there is an optional phase to listen to how fluent speakers achieve a similar task.

What is unique about this particular model is that the listening segment comes next, after the students have made their presentations. This is because the purpose of the listening exercise is to learn how native speakers resolve the issue or present their findings. The psychological principle for this placement after the students’ is that the learners must first externalize their own views and opinions before actually relax enough to have enough patience to pay attention to what others have to say about the issue at hand — not only concerning exposure to the content but also to the manner of their presentation (which is to say, both meaning and form). In this case, all of these issues are resolved by listening to the song itself.

In the final Language Focus stage, learners have the opportunity to notice the new aspects of the target language, that is, focus on form and ask specific questions about the language being learned. This stage is usually held in a whole-class forum.

Considering that this is a course for beginners, we take into account that the A1 level of the Common European Framework specifies knowledge of how to express one’s immediate environments and personal preferences in daily activities, so this lesson aims to foster learning about colours and their significances to Anglo cultures. Like the other Beatles songs chosen for the course, Penny Lane captures culture, a positive outlook, and also expresses intentionality via the phrases about what the characters habitually do.

To make this cycle operational, there is a single Pre-task stage for all the groups in the first two classes of the semester. In the first session, the teacher divides this class of about 25 students into groups of three or four, so there was one group for each unit. Each unit has its thematic Beatles song already chosen for it and the groups are asked to “take responsibility for the song” so that they have to “find a creative way to get the whole class involved” and “bring a bit of culture of the Beatles or of the sixties”. The idea is that affect, and thus motivation, would be derivative of creativity with the contents and with their classmates, ending up as an original piece of work.

The Pre-task stage continues on into other sessions where the teacher models the cycle by leading the class though Hello Goodbye for the first unit on introductions where they dance in parallel lines and gesture at each other to the lyrics “hello”, “goodbye”, “I don’t know”, etc. (Paloma Varela invented this vigorous jig and the mime to accompany it, 2009.)

When each group carries their session out, they de facto go through the three stages of the Task Cycle: Set the Task, Planning, and Report. They did extensive planning to make sure their own presentation is at least as theatrical as the previous ones. In the case of professions and Penny Lane, they make paper identifications for each profession. The barbers have scissors, the fire-fighters cardboard hoses with cellophane water spouting out, and so on.

First the little group leads the whole class through the lyrics, then they break up into trios and challenge each to raise and shake their identifiers when their profession is mentioned in the song — and of course to sing those lines at the tops of their lungs! Finally, for the analysis and report they ask each trio to indicate a unique point from their lines, be it spelling, grammar or culture.

Then for the equivalent of the Language Focus stage, the trio that presents the song makes a brief summary of what they have seen, along with a fair bit of culture of the period. Although they have played the song several times by now, everyone wants to do it yet again before time is over!

You can see a video of how it came out at these two links, (about 20 minutes total).

EFL Penny Lane 1

EFL Penny Lane 2

Because these classes were at the UPN, the teacher tagged on a second Focus stage which, rather than focusing on the English language, delved into the pedagogy underlying the teaching technique and motivation. If you understand Spanish you can watch this second Focus stage in the last minute of the second segment.

This article presented a handful of tasks in accordance with the principles for using authentic songs while simultaneously developing academic skills. Thus when students complete a project, the final written or oral expression is something they can be proud enough of to display because they have learned specific competencies appropriate to social practices of the language. (SEP, 2011: 11)

We would also like to point up that most authentic songs can be adapted to classroom use because they show the language which is negotiated world wide, therefore students get to know cultures, manners, slang, phrases, ideology, as well as fashion. Nowadays we as teachers are aware of preparing our students so that they exploit not only their language competences, but also life competences such as the intercultural competency.

We feel strongly that the more students interact with authentic materials, the better they will acquire the competence of learning-to-learn, because they learn to select, comprehend, analyse and summarize information so as to construct new knowledge in their learning-for-life process. A language teacher can also guide the students through the learning cycle by teaching the language components meaningfully and usefully, insofar as teachers are not going to conduct the students to answer nonsense gap-fill exercises, but rather to provide input in the successful high challenge step so that students will perform well in the low challenge and meet the criteria for their products in the assessment stage.

Blunt, James. (2005) You’re Beautiful. WMG. www.youtube.com/watch?v=oofSnsGkops (accessed August 2012)

Coordinación del Programa de Inglés en Escuelas de Preescolar y Primarias en el Distrito Federal. (2010) The Importance of Effective Planning. Mexico City: Secretary of Public Education.

García Salazar, Alma Delia and Otero Sosa, Alma Daniela. (2012) Great Ideas for Kids from 10 to 12 Years Old: Songs Inspire Delight in Words and Enrapture in Culture. Mexico City: MEXTESOL Saturday Workshop.

Otero Sosa, Alma Daniela and Siders Vogt, Terrence Nevin. (2012) Leading the Way to Excellence in Song and Intonation. Puerto Vallarta: workshop at MEXTESOL International Convention.

Secretary of Public Education. (2011) Programa Nacional de Inglés en Educación Básica: Segunda Lengua: Inglés. Mexico City: Secretary of Public Education.

Secretary of Public Education. (2010) The Importance of Planning a Lesson. Mexico City: Secretary of Public Education.

Siders V., T. Nevin. (2011) Una intervención educativa por televisión de la prosodia del inglés como lengua extranjera. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Siders V., T. Nevin. (2007) Stressed Out: Intonation for Beginners in TV Tutoring Sessions. in Humanistic Language Teaching, Year 9, Issue 6. old.hltmag.co.uk/nov07/mart03.htm

Varela, Paloma. 2009. personal interviews. Mexico City: Bridges.

Willis, Jane. (1998) Task-based learning. in English Teaching Professional, October 1998. p. 3.

The Wheels on the Bus. www.youtube.com/watch?v=wQGSQLcXMRA (accessed March 2013).

Please check the Methodology and Language for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching English Through Multiple Intelligences course at Pilgrims website.

|