Towards Imaginative Understanding: The Use of Film in Language Teaching

Michael Tooke, Italy

Michael Tooke is a teacher at the University of Udine in Italy. He has written on English for Academic Purposes and the teaching of History in schools and his main current interests are the ideas of Rudolf Steiner and their application to education.

E-mail: 1michael.tooke9@gmail.com

Menu

Introduction

Background

Examples

Conclusion

References

It is frequently said that the West is in a state of crisis: The economy has become impersonal and unstable; crime seems to be on the rise and we are suffering from an increasing sense of nervousness. It seems that we cannot continue as before, but need to find new ways to go forward. This article argues that what is most needed is a change in mentality, a move away from a so-called scientific view of the world to one of imagination that does not deny the value of science but takes it up to a higher level. Films can be an excellent means of developing such a move.

To understand what this means it is necessary to have a clear idea of the human being as such. For the purposes of the article, the human being is considered to be a complete whole containing three distinct parts, the three faculties of thinking, feeling and willing. Thinking can be said to reside mainly in the head, feeling in the rhythmic system of the chest and willing in our limbs and metabolism. These three parts interact within us and need to be kept in balance if they are to work in harmony together. The heart is the centre of the balance and thus acts as a go between or harmoniser for thinking and willing.

Modern life, however, tends to privilege the head over the heart in that thinking is considered scientific, while feeling is seen as untrustworthy and non-scientific. Science is founded on evidence, feeling is not.

This has a long history in Western culture and is arguably its central idea: the ego, or the thinker, has to stand back from what he observes to attain an objective understanding of it. He must do way with any preconceptions or a priori knowledge, gained for example via intuition, inspiration or imagination, as these are considered ill founded. They are mere idols or fantasies in the mind. The scientist needs to start by observing the world from without and then build up an idea of it step by step, in the faith that truth, constructed in a piecemeal way, will be revealed in the end.

The so-called scientific method of hypothesis, observation, analysis and further hypothesis is based on this idea. Even though it can be argued that on the ground science proceeds also via intuition and imagination, the process is basically a technical one. The more technical it is the more highly it is valued. We come to see the world in technical terms and thus regard it as a machine. This is totally transparent as it is what it appears to be and is neither more nor less than this. Each part has its particular function and can be separated from the others and then put back again. Such a view of the world is clear and makes us feel that life is safe and predictable.

The logical conclusion to this, however, is arguably the post modern condition. Science tends to calmly collect information in one direction until suddenly, or not so suddenly, a radical change occurs in the theory and another direction is taken. A certain sense of disconnectedness and fragmentation enters. It is felt that there are no truths, but only opinions – as Woody Allen declares in his film, “Whatever Works”, what works, goes. Truth is only in the mind.

Such a system of knowledge, therefore, with its basic ontological move, prizes analysis over imagination and separates thinking from feeling. It is naturally also the essence of present academic thinking. Of the many “isms” in academic theory, it may be enough to take one example.

Orientalism, whose main proponent is probably Edward Said, looks at culture in terms of power. Any depiction of the East by the West is seen as a bid for supremacy over it, Western writers forming their discourses out of their desire to dominate other cultures. The central image is that of a battleground. Culture is conceived as a war in which everyone tries to win against an opponent and discourses become tactics in a war game.

The effect of this, however, is arguably devastating. It reduces culture to a calculation – a game that seeks certain ends – and thus mechanises our relationships with others in such a way that we are in danger of becoming calculating egos, involved in competing with everyone else in a war of all against all. There is no truth, but merely opinion that seeks to make itself heard. In effect we have entered the post modern condition.

However, it is possible to raise ourselves out of such a condition and go beyond the merely mechanical view. Science has taught us rigorous observation, precise analysis and the rational exploration of nature. To go beyond means to take these qualities with us in an attempt to revitalise knowledge and change science into a living conception of the world. The basic move of modern science whereby the ego separates itself from the world is changed so that the ego and the world merge again – we do not detach ourselves and observe the world from outside, but enter the world in such a way that it becomes an experience for us. We use creativity, rather than destruction, to link parts together and thereby move from a purely intellectual to an imaginative way of thinking. In this way we restructure our thinking, feeling and willing so that the heart takes back its place at the centre and we are able to recapture the big questions about who were are, why we are here, where we are and where we should be going.

Imagination can be defined in innumerable ways. For simplicity’s sake we can refer to the romantic view and specifically to Wordsworth in his poem, The Daffodils.

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils

Here imagination is referred to as recollection in tranquillity. The starting point is an experience, something lived through by the author, not a fact, a statistic or an idea. This is then revisited by the mind: the heart thereby brings life to the head, while the head guides the heart. Such a procedure may analyse the experience and thus break it down into separate pieces but with a view to recombining them creatively. This is no fantastic recombination, but a reconstitution of the experience itself.

A film is an ideal way to develop such imagination as it tells a story which the viewer “experiences”, proposing a reality within which he can immerse himself – like Wordsworth in the field of daffodils. In creating such an experience the viewer in a sense participates in it. It thus provides a context in which to develop a lesson. Having provided the experience, the lesson then takes the viewer back over it to explore, examine and analyse in order to guide his understanding. We are no longer dealing with sound bites or fragments, but a self contained and yet infinitely revealing story, which does not seek to elicit opinions, but calls for an exploration of the truth of the experience. This process thereby removes us from the mechanistic cause and effect process to a living understanding of reality.

A film needs to be chosen with this in mind, but once a film has been chosen, particular scenes have to be selected for work in the classroom. It is possible to focus on one scene only. This, rather than the film, then becomes the centre of attention. On the other hand it is possible to select a number of scenes so as to explore the whole film more closely. In the latter case, it may be better to take a maximum of three as any more can become cumbersome and unwieldy. These three scenes will form a thread throughout the story, perhaps reflecting the main plot, concentrating on certain of the characters or highlighting a subplot of the film. Again these need to be chosen carefully. However, it is not necessary to see all of them. We could use only one as a listening exercise and cover the others via another activity such as a reading.

The following example is a film by the director David Lean: A Passage to India. Adela has come out to British India to marry Ronny, a district judge. She is accompanied by his mother, Mrs. Moore. She wants to “see” India, so the head teacher at the local school, Dr. Fielding, arranges for her and Mrs. Moore to meet a friend of his, Dr. Aziz and a teacher at the school, Godbole. At the tea party Dr. Aziz invites them to the Marabar Caves. He organises a grand picnic, but in one of the caves, Adela, dizzy, overheated, confused by their airlessness breaks down and runs madly away. Dr. Aziz is accused of attempted rape and the two communities, Indian and British polarise. At the trial Adela recognises she has made a mistake, which she admits and consequently causes a riot. She leaves India, where she had gone with such high hopes, despised by both British and Indians.

The first scene is a tea at the school house where Aziz invites the English ladies to the Marabar caves. On the first listening students have to identify where the characters plan to go, on the second to identify who said what to whom. This is followed by an exploration of the characters and their relationships to each other, and a language exercise that requires an understanding of why particular characters use particular language. This leads to an imaginative exercise where the students are asked to imagine how a belief in reincarnation would change their lives (figure one).

Watch the video and answer these questions:

Where do they want to go? What is the place they decide to visit like?

Watch a second time. Who says what to whom?

| 1. By skilful arrangement of our emperors, the same water comes and fills this tank. |

|

| 2. The sun will soon be driving us all into the shade. |

|

| 3. I’m afraid we may have given some offence. |

|

| 4. They even put off going to Delhi to entertain us. |

|

| 5. I do so hate mysteries. |

|

| 6. I rather like mysteries, but I do dislike muddles. |

|

| 7. There’ll be no muddle when you come to visit me at my house. |

|

| 8. Let me invite you all to a picnic at the Marabar caves. |

|

| 9. Immensely holy, no doubt. |

|

| 10. They are all the same, empty and dark. |

|

| 11. Don’t you come, Adela, I know you hate institutions. |

|

| 12. When I first saw Mrs. Moore it was in the moonlight. I thought she was a ghost. |

|

| 13. A very old soul. |

|

| 14. I have contrived a dance based on this philosophy |

|

Discuss these questions in small groups:

- How would you characterise each person? Which characters would you say are talkative, cold, emotional, naïve, wise, disinterested, proud, detached, impetuous?

- How are the characters different from each other?

- What is the difference between these phrases:

| The sun will soon be driving us into the shade |

The sun is going to drive us into the shade |

| I’m afraid we may have given some offense |

We probably gave some offense |

| I do so hate mysteries |

I hate mysteries |

| I rather like mysteries, but I do dislike muddles |

I like mysteries, but not muddles |

Why do the characters in the scene use the phrases in the first column?

- How would your views of others, your past, your future, the meaning of life change if you believed in reincarnation?

|

Figure one: Worksheet (Scene One)

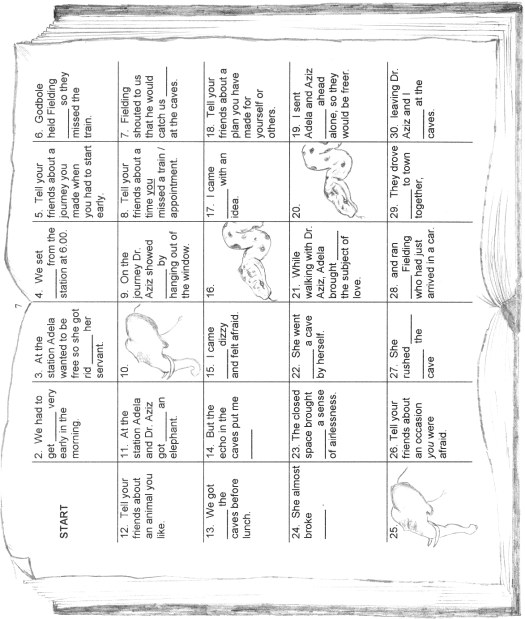

The second scene covers the Marabar caves. We imagine that Mrs. Moore kept a diary of the event (figure two). In groups of three, students move round the diary trying to complete the phrasal verbs, with one student providing the answers from an answer sheet; at the same time they are learning what happened at the picnic. Several squares also ask them to talk about themselves (e.g. talk about a journey where you had to start early) so they can integrate the Marabar experience with their own.

The final scene is a second listening exercise in which some of the immediate results of the picnic are seen and further language work is done on modals (figure four). Such words point to the attitudes and underlying beliefs of the characters and the director himself. In the dialogue will is often used. Whereas students often say will is a weak form of future as opposed to going to, here it is clear that this is not the case. On the contrary will expresses force. We might say it basically expresses the will of the world, of God. It is the power behind the universe that lives in our will. Its basic meaning as prediction indicates that it is beyond our control. It refers to something that is bound to happen. This essential meaning colours the other uses of will. Here the “I won’t be quiet” is very forceful. A promise or refusal is a direct expression of our will. There is something solemn in it.

Going to as prediction, on the other hand, has to do with logic not destiny. I can see that something is likely to happen. I have the evidence in front of my eyes. Therefore I can deduce that such and such will happen. The car is driving too fast. It is going to crash. Here the force of going to is in the rational calculation of events. This makes the meaning closer to going to as intention which again is a calculated idea in the speaker’s mind.

The use of would is not hypothetical but refers to the general tendency of the character (it is not a thing he would do). His temper is like that. As a result what he does, what he wills, will be of this nature.

Finally, Has got to as opposed to must seems to suggest that a higher authority is involved The affair must come before the judges because it has been decreed by the gods, not just because the speaker says so.

Figure two: worksheet (Scene two)

Thus, the exploration of these modals, especially when compared to Godbole’s language from the first scene (the sun will soon be driving us into the shade) emphasises the sense of the will of God, the fatality behind the affair, highlighting the preoccupation of the director David Lean with questions of freedom and human destiny.

| Adela |

C: She's been complaining about an echo in her head.

M: What about the echo?

C: She can't get rid of it.

M: I don't suppose she ever will.

C: Back in a moment.

R: Mother, that was unkind.

M: Unkind? Unkind? What about poor Dr Aziz and those terrible police?

R: Mother, quiet, please.

M: I won't be quiet. Aziz is certainly innocent.

R You don't know that.

M: l know about people's characters. lt's not the sort of thing he would do.

R: Whatever you think, the case has got to come before a magistrate now.

The machinery has started.

M: Yes. She has started the machinery. It will work to its end.

|

Figure three: worksheet (Scene three)

As a final exercise the students can be asked to predict the end of the film, reviewing the modals above. They look at the sentences in figure six and decide if they agree or not and why. They can then ask a student who has seen the film, or the teacher, to answer the questions and talk about the end of the film.

| The trial |

What do you think the trial will decide? Do you agree or disagree with these points?

- In no way will the English give in.

- The Scottish lawyer will be kind to Adela.

- Adela may well describe the rape in every detail

- Aziz will definitely be sentenced to prison.

- Fielding might help Adela to recover.

- Fielding will help Aziz in prison.

|

Figure four: worksheet (final questions)

Here knowledge is constructed on the basis of first entering an experience, that offered by the film. This is then recollected and examined in depth (analysed scientifically) and finally directed in an imaginative exploration of its various meanings. The learner works inside the story rather than as a mere spectator. In so doing the knowledge gained becomes an integral part of us – the world is fitted together rather than reduced to fragments. A general meaning is created and connections made between the parts – with the people and circumstances of the film. Thus, the purely scientific approach which has taught us to analyse “objectively” is taken one step further: the self and the world re-find each other. In this way, the world is re-created and revitalised rather than deconstructed and destroyed.

Allen, W. (2010) Whatever Works

Gray, J. (2010) The Construction of English Cultures, Consumption and Promotion in the ELT Global Coursebook London: Palgrave Macmillan, p.26

Lean, D. (1984) A Passage to India

Leech, G. (1981) Meaning and the English Verb London: Longman, p.73

Said, E. (1985) Orientalism Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, p.3

Steiner, R. (1981) L’Educazione, Problema Sociale. I retroscena spirituali, storici e sociali della pedagogia applicata nelle scuole steineriana. Milano: Editrice Antroposfica, p.59

Steiner, R. (1987) Gli Engima della Filsofia Roma: Tilopa p. 71-72

Steiner, R. (1992) Come si puo’ superare l’angoscia animica del presente Oriago: edizione Arcobaleno , p. 29

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|