Psychology and ELT: Changing Attitudes. A Beginner’s Guide to Persuading Yourself!

Nick Michelioudakis, Greece

Nick Micheiloudakis (MSc, Dip RSA) is a teacher / trainer based in Greece. His interests include comedies, student motivation, as well as Social and Evolutionary Psychology.

E-mail: nickmi@ath.forthnet.gr www.michelioudakis.org

Menu

From action to belief

Chinese indoctrination

Applications in the field of ELT

Away from ELT

References

E. Tory Higgins wanted to investigate how actions might affect our perceptions of reality. To this end, he gave a group of subjects a description of a fictional person – let us call him ‘George’. Half the subjects were then asked to summarise this information for someone who liked George, while the others had to do the same thing for someone who hated him. Naturally, the former focused on George’s positive qualities in their summary, while the latter were far more negative about him. Here comes the interesting part however: some time after that, both groups were asked to write down what they recalled from the original description. Amazingly, the first group recalled George as being a much nicer guy than the latter! As Levine points out (2006) ‘you adjust your presentation to please the listener and, in so doing, convince yourself in the process!’ Brilliant!

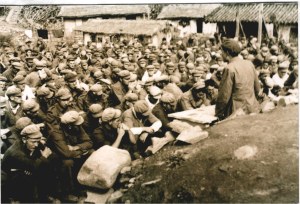

The example above points to very important principle of how persuasion works – only Big Pharma were not the first ones to stumble upon it! As Cialdini writes (Cialdini 2001) when American POWs returned from Korea following the armistice in 1953 the US military were shocked to find that many of them had come to embrace many of the key beliefs of the Communists to a far greater degree than anyone could have expected! Had they been brainwashed? Far from it.

So how did the Chinese do it? Showing a profound understanding of human psychology, they would start by asking US servicemen if they thought the US was perfect. Well, nobody and nothing is perfect, right? Then they would ask them to say if they could think of 2-3 things which were wrong about the US – perhaps wealth distribution was unequal? In the same way, they would ask them to mention 1-2 things that were positive about Communism – perhaps the fact that there was no unemployment… Next they would ask the American POW to say why he thought this was so – and also perhaps to write these things down and sign them. Well, what is wrong about writing down your views? After all they are what you believe, right?

With the offer of paltry rewards, they would then ask those US soldiers to talk to others about these things – nothing that they did not believe in! And then perhaps they could answer some questions… By now, you can see where all this was going… Before long, these US prisoners had moved from being ordinary servicemen loyal to their country and its values to fierce critics of what they saw as the negative side of capitalism – and nobody had coerced them in any way! How had this happened?

As Ariely (2012) points out, psychology research shows that we tend to believe what we say – ‘even when the original reason why we said it is no longer relevant’! In this case the Chinese had made use of this basic principle and used it in conjunction with a number of others (this is where you should take out your notepad! :) )

Graduated commitment: Experience has shown that it is easier to start small and gradually move up – it is easier to justify these small steps to oneself.

Putting things in writing: Perhaps writing focuses one’s attention – perhaps the fact that we see something there in black and white somehow ‘fixes’ certain ideas as firm beliefs (Levine 2006)

The importance of one’s signature: This activates the ‘Cognitive Dissonance’ mechanism – somehow we have bound ourselves to what we have signed (Ariely 2012). Backtracking would have serious repercussions on our self-esteem.

Constructing reasons: The brain does this automatically (Tavris & Aronson 2008) but encouraging this process tends to allow ideas to ‘grow roots’ – regardless of how valid the reasons may be.

Going public: Time and again, research has shown that once we go public we have irrevocably committed ourselves to an idea / cause (Goldstein, Martin & Cialdini 2007)

If the Chinese could do it then surely so can we, right? Indeed, we should not have to indoctrinate anyone, because ideally students (ss) should come to us wanting to learn! Alas, this is not always the case. And even if it were, motivation is not a ‘Yes/No’ answer to a question – instead, it can best be seen (like so many other things in life) as a continuum! That means that regardless of the level of our ss’ motivation we can still give it a boost! Here are some ideas:

Mini talks / essays on the importance of English: If ss can come up with reasons themselves, they are more likely to believe them and hence become more motivated. But what matters is the process of expressing these reasons – preferably in public, before their peers. Naturally, the same technique can be used to foster any kind of desirable behaviour (e.g. being punctual). We simply ask them to argue in favour of it.

Sharing tips: Getting ss to swap ideas about the most effective ways of studying is beneficial in many ways: a) it may give ss ideas which they might not have thought of b) the message is more persuasive as it comes from their peers (Brizendine 2010) and c) the more someone expounds on the benefits of a particular technique, the more likely they are to use it themselves!

Peer teaching: Peer teaching operates in a similar way. The adoption of a particular role, even in make-believe situations, often leads to the adoption of certain values and ways of behaviour. * Once again, ss stand to learn from what they will try to teach, but more importantly they are likely to become more mature and responsible learners as a result of taking on the role of the teacher (Dornyei 2001).

Getting students to help: I have found that asking ss to help with things like tidying up the classroom, cleaning the desks or decorating the walls works wonders! The direct request creates a bond between ss and T, the process of creating a suitable learning ‘context’ drives the point home that the learning process itself is important and, crucially, because of the effort they expend, ss come to see the place and, by association, the lesson in a more positive light.

Playing devil’s advocate: Debating with the ss (e.g. about the importance of H/W) is another way to get them to see things from your vantage point. You can set it up as a fun role-playing activity: you, the T, is going to be the ‘unruly teenager’ and the class can be the T or the teenager’s parents. As is the case with the first activity the topic can vary depending on what it is you want to focus on. Of course you don’t want to play your role too well as a) your ss may get stumped for lack of arguments and b) you may end up persuading yourself! :)

But do such things happen in real life? You bet they do! Here is a good case in point (taken from Ariely 2012). Imagine Jane, a sales rep from one of the Big Pharma companies who approaches a doctor (say John) to tell him about a new drug. She will then ask John to give a mini talk to other doctors or medical students or even other reps about how the drug works and the ways it might help the patient. The doctor after all is the expert! Now here is the interesting detail: the rep does not care about the effect of the talk on the audience; the primary target of the talk is….the doctor himself!! Never mind that he gets paid; the fact that he talks about the drug’s advantages means that later he is far more likely to prescribe it himself!!

* The negative side of this principle was grimly illustrated by Zimbardo’s notorious prison experiment (Aronson 1999)

Ariely, D. “The (Honest) Truth about Dishonesty” HarperCollins 2012

Aronson, E. “The Social Animal” Worth – Freeman, 1999

Brizendine, L. “The Male Brain” Bantam Books 2010

Cialdini, R. “Influence – Science and Practice”, Allyn & Bacon 2001

Dornyei, Z. “Motivational Strategies in the Language Classroom” Cambridge 2001

Goldstein, N., Martin, S. & Cialdini, R. “Yes! 50 secrets from the science of persuasion” Profile Books 2007

Levine, R. “The Power of Persuasion” Oneworld 2006

Tavris, C. & Aronson, E. “Mistakes were Made (But not by Me)” Pinter and Martin 2008

Please check the Building Positive Group Dynamics course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Dealing with Difficult Learners course at Pilgrims website.

|