Stories: The Most Natural Carriers of Communication and Learning

Nick Owen, UK

Nick Owen is Director of Nick Owen Associates Ltd., a learning and development organisation that specialises in developing leaders, communicators, and influencers to operate in today’s challenging contexts. His clients range across FTSE 100 companies, educational institutions, health services, as well as some of the poorest and least privileged communities in Africa and South East Asia. He has worked extensively with the British Council and has been an Associate Trainer with Pilgrims and NILE [Norwich Institute of Language Education]. His philosophy is that learning and development should be sustainable, useful, multi-layered, and fun. E-mail: nick@nickowen.net

Menu

Introduction

Background and overview

A book by book analysis

Busy-ness

Float like a butterfly; sting like a bee

Management wisdom

References

Links

The land is dry and a man digs a well to find water for his gardens. After working for several hours in the spot recommended by the water diviner he finds nothing and gives up in frustration. He has dug about four metres.

As he sits on the great mound of soil, a traveller passes by. The traveller laughs at him for digging there, and indicates a much more likely location. So the man starts a new well, but after digging for five or so metres, he has still found no sign of water.

Feeling tired and rather disappointed, he finally accepts some different advice from his old neighbour who assures him that he’ll find water in yet another place. After he’s given up on that one too, his wife comes out of the house and says, “Where are your brains, man? This is no way to sink a well. Stay in one spot and go deeper and deeper there!”

The next day, having slept deeply and recovered his strength, the man returns to the first hole and spends all his time and concentration in that one place, and finds abundant water deep below the surface.”

I have loved stories since I was a child when my mother used to tell them to me at bedtime. Now, many years later, I have lost none of my passion and enthusiasm for listening to a well-told story, or reading one from a book.

What’s the attraction? Stories are the common currency of communication. If we think about it, all our conversations – even the ones we have with ourselves – are in essence stories. We meet a neighbour in the street, we chat to colleagues around the coffee machine, we discuss a student at a staff meeting: what we share are stories. This happened, and that happened. She did this; he did that, and so on.

Stories are how we make sense of our experience, how we code our reality, and how we learn that there are other perspectives than the ones we currently hold. Through stories we discover different ways of making sense of this rich, complex and amazing world we inhabit, and different ways of approaching and understanding what we perceive as ‘reality.’ Stories are a key medium through which each one of us transmits information and through which we learn and develop.

Engaging, relevant, well-told stories are universally appealing. The human brain is engineered to pay attention to a good story and there are many reasons for this. They have a structure, an internal logic, and a set of relationships. They are experiential, multi-sensory, and appeal to multiple intelligences. They address the left brain’s hunger for order, analysis and structure, and the right brain’s thirst for imagination, emotion, creativity, and the unexpected. They are contextual: no matter how fabulous that context may be each story has its own contextual integrity. Above all, they are memorable, replicable, and engage with the listener’s curiosity and world-view.

And yet, no-one owns a story. Whatever the teller of a story thinks her story is about, the receiver may have other ideas. Take the story above. It is on the surface a very simple story, but it has a wide range of possible interpretations as the individual complexity of the listener’s world invites a diverse range of metaphorical possibilities. Here are some:

- Follow your outcomes through to the end;

- Don’t give up too easily;

- Don’t get distracted;

- Don’t get dejected if things don’t work out at first;

- Don’t dissipate your energy on too many projects;

- Advice is cheap and often unreliable;

- Some people know what they’re talking about; find out who they are;

- Practical people make good partners;

- Pay attention to quality feedback;

- Trust your own judgement and stick to your guns;

- Take responsibility for your own actions;

- Meditation isn’t about losing yourself; it’s about focusing on and attending to one thing at a time in great depth;

- The richest jewels lie in the deepest seams;

- Wisdom is attained through struggle with yourself and the world you inhabit

On the surface the story appears to be about one man’s need to water his garden. But imagine the impact it might have on a group of thirteen year olds who are getting impatient because they cannot quickly master learning something that takes time and patience -like a complicated riff on the guitar or the structure and various functions of the present perfect tense. The story offers a gentle and indirect suggestion that some things in life require time and application.

The fact is that stories are the most natural form of communication in language and they have multiple uses and applications not least in the classroom.

I have enjoyed working with and telling stories so much in my life that I have now written three books about stories and metaphors. In fact, the story of the man and the well is the story with which I begin my very latest book, The Salmon of Knowledge: Stories for Work, Life, the Dark Shadow, and OneSelf.

The first book, The Magic of Metaphor: Stories for Teachers, Trainers, and Thinkers, was published in 2001. It came about because many teachers with whom I was running teacher training and development seminars kept asking where I got my stories from. I would use a wide variety of stories to illustrate the points I wanted to communicate: stories that would introduce a grammar structure, a function, or particular vocabulary set in a clear context; stories that would suggest a variety of ways of looking at a particular issue; stories that would illustrate the benefit of a certain mindset or attitude; stories that would explore cultural differences and values; stories about my personal experiences of life, teaching and learning, of great successes and heroic failures.

‘Stories,’ I would tell these groups, ‘are all around you: within you, heard from friends, in the newspapers, in books and movies, on TV. Go out and find stories of your own.’ But still they persisted until I thought ‘Why not? Why not write down my stories as a book? Write a book for teachers and communicators!’ And that’s exactly what I did.

More Magic of Metaphor: Stories for Leaders, Influencers and Motivators [2004] was written because I wanted to explore through stories, and bring to wider attention, two deeply powerful models of the world that I believe have a great deal to offer in terms of better understanding human development, learning, and sustainability. They also offer important insights into motivation, education, and new paradigms of leadership. A key element of these models is the recognition that learners, whether young or adult, at different stages in their development require very different methodologies to learn effectively. In these models there is no room for a one-size-fits-all approach.

The Salmon of Knowledge: Stories for Work, Life, The Dark Shadow, and Oneself [2009] invites the questions: what is a mature human being? How can we aspire to becoming such a thing ourselves? And how can we inspire others to do the same? The background context for writing this book is the current madness infecting much of the world in which large sections of the human race appear to have lost all sense of what really matters in life. It is not only the current and universal chaos in the financial markets caused by greed and short term thinking, but also education’s obsession with facts and testing, and the undiscriminating desire of so many to seek comfort and self-worth only in material acquisitions and mind-numbing distractions. That dark shadow – our ability to lose ourselves in greed and self-deception – lies within all of us. This is a somewhat darker book than the previous ones, yet still celebratory of the inner goodness and greatness that also resides within each of us.

Through stories, some based on my own life and experience, and others drawn from a four thousand year tradition of secular and spiritual wisdom stories, this book explores the importance of re-connecting to what it is that makes us truly human. The stories affirm that each of us, as well as having a rational self that knows which one washing powder to choose from the many ranged along the supermarket shelves, has a deeply spiritual aspect too. An aspect which offers – when we connect to it – a far more satisfying and deeply transforming experience of connection and integration to ourselves, others, our work, and our planet than anything the rational mind can conceive of.

And to do this we also have to develop a deeper understanding of our psychological self, and stories are a great way to get to know ourselves and others better. There are over 140 stories in this book, short and long and from all corners of the globe, that invite us to look more closely at self and others and ask ourselves some illuminating and challenging questions.

I was delighted when Mario Rinvolucri and Hania Kryszewska asked me to write an auto review of my books. But I was a little confused too never before having written such a thing. It certainly wouldn’t be appropriate to evaluate my books but I can offer a description of what you will find inside each one. I also feel comfortable about referring readers to www.amazon.co.uk where you can click on Books and then click on Nick Owen where you will find an array of independent reviews on the books. And maybe it’s also useful to mention that the first two books have been translated into several other languages including Chinese, Russian, Italian, Spanish, Swedish, Romanian, and Estonian. The Magic of Metaphor has done particularly well in this respect.

Generally speaking the most important element in all the books are the stories themselves and the books are a very useful resource for anyone who is serious about using stories in their work and life, or even just reading them for pleasure or edification. In all there are nearly three hundred stories covering just about every theme imaginable in the books, and their provenance is from just about everywhere on the face of the planet. The stories are the stars and speak for themselves; the packaging around them gives them shape and direction and points the reader towards certain key notions and perspectives that I have thought useful and important at the time. Above all I wrote the books to explore my own ideas, my thinking, my own unformed intuitions and to bring them closer to the surface of my awareness.

Inside The Magic of Metaphor you will find an Introduction, the stories divided into six key themes, and a final chapter on applications. The Introduction offers an overview of the book, and short sections on the many uses of stories, the power of stories, meaning and interpretation, and some essential tips and suggestions on the art of telling stories with success.

The stories are organised into the following themes: Pacing and Leading which explores the importance of relationships and inter-relationships; Value Added which looks at the difference values make in our lives; Structures and Patterns which investigates the human propensity for using strategies, some of which work for us and some of which don’t. Response-ability invites us to become the stars in our own movie and take personal responsibility for everything we do. Choice Changes suggests that we inhabit a reality where the quality of the choices we make affects the quality of our life and of those around us. The last theme, Transitions, moves the reader beyond the book and into what is to come.

The last section, Some Ways to Use the Metaphors and Stories in the Book, offers the reader a range of effective ways to use the stories in a variety of contexts from classroom teaching to business presentations. It takes a number of the stories from the book and gives a step by step account of how they can be framed, used, adapted, and exploited to maximum benefit for storyteller and listeners. The Magic of Metaphor has been a best selling title for eight years now, and appears on various college and university booklists as required reading.

More Magic of Metaphor contains about the same number of stories as the previous book [roughly 80] but its aims and intentions are rather different. This is a book that uses story to explore the notion of leadership in its very best sense and across all possible applications from parenting, to teaching, to business, to statesmanship. We are all leaders at various times in our lives and in a wide variety of different contexts. Above all, the person we most need to lead is none other than ourselves. Indeed, how can we even begin to think about leading others until we have some clear notion about who we are, and how we run our own life?

The first book was structured around an on-going dialogue between a Magician and her Apprentice. This device allows for an easygoing flow of questions and answers around the Why? What? How to? and Where can I use these ideas? of stories and storytelling. In the second book, the Apprentice has graduated to a Journeyman Magician and is given a task by the Master to “seek out and explore key attributes of leadership. What inspires people to change, learn and transform, and –moreover – how can you influence and motivate them to want to do so?”

Travelling through time and space the young Magician does just that, collecting and commenting on stories of leadership as he goes, aided and abetted by a wise travelling companion. The wise companion introduces him to two powerful models of development that enable the young man to interpret the stories with much greater depth and understanding and to realise how different stories resonate differently with people at different stages in their development.

The first of these models is known as Spiral Dynamics [SD] and sits in the discipline of development psychology. It recognises that children [as Piaget demonstrated] and adults both have the potential to continually develop complexity in their thinking and valuing as they mature. This has enormous implications in all aspects of society. In education, it has many applications but of particular importance is the realisation that different students at different stages of their development need access to markedly different methodologies in order to learn well. They also need different teaching styles as they evolve, and different strategies to get them motivated. The book explores this in some detail both through the stories and in a special appendix at the end.

The stages are coded by colour and to give you a flavour of the model, the different learning/teaching styles can be rendered simply in the following ways:

Students centred at PURPLE need an elder, a father or a mother figure to guide their learning and development. Think primary school. At RED, they require a tough boss who will police the boundaries, challenge their exuberance, and offer tough love. At BLUE, they look to find a properly qualified teacher, an authority figure who supports them in their quest for structure, rigour, and a clear future vision. At ORANGE, students seek a street-wise teacher, one who knows how to apply knowledge in real world scenarios and works with cutting-edge ideas and modern technology. At GREEN, students look to find a facilitator to guide them and to consensually share power and decision making with them. Finally at YELLOW, the teacher acts more as a consultant, supporting learners centred here to become increasingly more autonomous in their life and study.

This is just a snapshot but it becomes possible to recognise how helpful this framework can be, and why – for example – certain methodologies do not work in certain contexts. Humanistic methodology, for example, is part of the GREEN stage. It will be effective only when the students are mature enough in their development to accept it and recognise its value. If they live in a tough inner city estate, where gangs roam the streets and life is edgy, it’s a dog-eat-dog world. Chances are, these students will respond much better to a methodology which paces their RED world view and step by step leads them towards a BLUE orientation.

The second model, based on the work of American philosopher Ken Wilber, requires us to consider the complex nature of the world we inhabit and the importance of approaching everything we do, from education to business, from ecology to politics, in a systemic and sustainable way.

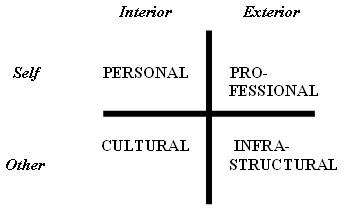

There are four territories of experience that we need to consider if our work and contribution is to be effective and sustainable. The four areas are: personal consciousness and awareness; behavioural and skills development; cultural awareness [in the very broadest of senses]; and how we fit in with the infrastructural contexts in which we operate.

The model, known as ‘A Theory of Everything’, looks like this:

The left hand quadrants are to do with our interior world of consciousness and values, awareness, shared codes and shared ‘languages.’ These quadrants are largely intangible and non-measurable. The right hand quadrants are to do with the exterior reality we inhabit. They are tangible and measurable.

The top quadrants are to do with ourself; the lower quadrants to do with other people and things, and our relationship to them. Infrastructural, by the way, refers to the material and structural elements in our environment such as architecture, hierarchies of power, sophistication of communication systems, availability of textbooks and equipment, et cetera.

Because the left hand quadrants are hard to measure, they have tended to be dismissed or ignored in our rational western world. This is true both in business and education. And yet it is the left hand quadrants that make us more human, that add real quality to our lives, and allow us as individuals and communities to develop and transform. Yet it is not either/or but both/and. We need to operate in all the quadrants in an integral way.

It is often said in business that managers tend to operate out of the task-based right hand quadrants [doing things right], whereas the best leaders tend to operate more out of the left hand relational quadrants [doing the right thing]. In teaching, in my experience the best teachers are the ones who not only know their stuff and how to get the best out of the system [right hand] but more than anything else know how to build great relationships with their students and colleagues and inspire and enthuse all those around them [left hand].

An organisation is only as good as the vision and commitment of the people who work in it. A school is only as good as the quality that its staff and students collectively and individually bring to it. A key question all leaders and teachers must ask themselves is: how can I create a culture in my team or class of students that enables each one to make a contribution and thrive in whatever ways are currently right for them. As the saying goes, ‘An excellent farmer doesn’t grow crops. He or she creates the conditions and environment in which the crops can grow by themselves.’

Through stories and an on-going dialogue about the stories, their meaning, and relevance to life and work I have endeavoured to make these two extraordinarily valuable models available to as wide an audience as possible. In the challenging times we are living through, and where even more challenging times are likely to come, these models may be part of the toolkit we need to help us create a more sustainable world in which we can live with greater integrity and awareness. And even if you don’t want that, you can just enjoy the stories.

Thus the latest book, The Salmon of Knowledge, is very much in the same tradition: how do we cope, and develop ourselves and others, in an increasingly difficult and uncertain world.

On my business card I describe myself as ‘Catalyst.’ And that feels right because, like grit in an oyster, my function is to create conditions so that others can make the changes they desire. But the times we live in seem to call for something more. Asked recently by the innovative leadership team of a global organisation how I would describe myself the word that surfaced was ‘healer.’ Healer in the original sense of the word, as in the .Old English hælen: to make whole, to reconnect.

It is this need for reconnection, for a much deeper systemic awareness in a fragmented world that has shaped my writing of The Salmon of Knowledge.. How can we develop deeper and more satisfying relationships with our work, our world, with others, and most of all with ourselves? How can we go beyond the current limited understanding of ‘wealth’ as the ownership of material possessions to a deeper recognition that true wealth embraces so much more than this? After all, the word comes from the Old English wela meaning well-being.

Two strands of human thought and experience point to possible ways of achieving deeper connection, awareness, and wealth. The first is cutting edge science with its notions of indivisibility and inter-connectedness found in quantum mechanics, relativity, complexity and systems theory. The second is the body of stories and analogies handed down from the great secular and spiritual wisdom traditions. There is far more overlap between these two strands than one might imagine.

Einstein pointed to this last century when he wrote: The rational mind is a faithful servant, the intuitive mind a divine gift; the paradox of modern life is that we have begun to worship the servant and defile the divine. The ancient Irish legend of the Salmon of Knowledge, written in the third century AD makes exactly the same point: the mature human being is connected to both his rational marketplace self and his intuitive spiritual self.

There are well over 140 stories in this collection, from ancient to contemporary, from all points of the compass, organised by theme, and which suggest ways to see ourselves and our organisations less as discrete items in a faceless, mechanistic universe and rather more as unique dynamic forces operating inter-dependently within an immense and utterly fascinating wholeness.

The stories invite us to wake up, stop taking ourselves so damn seriously, look at the world from perspectives other than our own, and recognise that only by changing ourselves can we reconnect with what is truly important in life. The stories offer ways to do just that for, to slightly paraphrase the words of the great Zen Master, Dogen Zenji, if you want to know the Truth first you must study yourself.

Here are three stories from the new book:

A successful businessman asked a monk: “What do you do to make a living?”

“Nothing,” the monk replied.

“Isn’t that laziness?”

“Not at all. Laziness is the art of finding countless ways to distract yourself. Usually, being ‘busy’ is a strategy people use to avoid asking themselves the really difficult and necessary questions that most need to be asked. Most often, laziness is the vice of people who are too busy.”

The root of the word business, incidentally, comes from the Old English bisignis, meaning anxiety.

The Buddha was wearing his transparent cloak of non-striving mind. He seemed to float across the ground, moving with the grace and elegance of a panther.

People noticed. “Who are you?” asked a group of by-standers.

“Wrong question,” he replied. “The question you want is: What are you?”

“Oh! I see,” said one of the group. “In that case, what are you?”

“Awake!”

Peter Drucker, sometimes called ‘The Father of Modern Management’, was once invited to speak at a celebrated business school at a prestigious university in the USA. The topic was ‘The Secrets of Great Managers.’

He stood in front of 3000 leaders, managers, and MBA students and said, “People are not mind readers. There are just two secrets to great management: if you want something ask; if you need something say.”

He turned on his heel and walked towards the exit. But before he could reach the edge of the stage, a voice called out. “Is that it?” He paused. “No. There is one more thing.”

The audience waited.

“Be brief.”

Then he left.

Beck D. & Cowan C., Spiral Dynamics: Mastering Leadership, Values, and Change. Oxford and Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1996

Owen N., Applications of Spiral Dynamics in the Classroom [article]. Self published, 2004

Wilber K., A Theory of Everything. Dublin: Gateway, 2001

nick@nickowen.net

www.nickowen.net

www.crownhouse.co.uk

The Magic of Metaphor, Crownhouse Publishing, Carmarthen 2001, ISBN 978-189983670-3

More Magic of Metaphor, Crownhouse Publishing, Carmarthen 2004, ISBN 978-190442441-3

The Salmon of Knowledge, Crownhouse Publishing, Carmarthen 2009, ISBN 978-184590127-1

Please check the Train the Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the The Literature course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Coaching Skills for Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|