Acknowledgement

I am indebted to Professor Jolanta Szpyra-Kozłowska for all her help and constructive advice in the completion of this paper.

Intonation in Teaching Pronunciation: In Search of a New Perspective

Dariusz Bukowski, Poland

Dariusz Bukowski is an EFL teacher and teacher trainer at Grafton College of Management Sciences in Dublin, Ireland. He has written and presented several papers on teaching pronunciation. His main interests in TEFL are teaching the skill of speaking and pronunciation in a student-centered environment.

E-mail: darbuk@tlen.pl

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Intonation – to teach or not to teach?

Approaches to teaching intonation

Intonation in ELT course books – a critical view

Conclusion

References

The paper argues that intonation, owing to its linguistic functions, can, to some extent, be responsible for the students’ level of success in communication. It contains an analysis of selected ELT materials and demonstrates a visible bias towards teaching mainly the grammatical and attitudinal functions of intonation. It claims that the lack of communicative, discourse oriented activities seems to clash with the contemporary communicative tendencies in foreign language teaching, which calls for a change in intonation teaching syllabuses by introducing and gradually increasing the amount of discourse intonation practice.

Like a pendulum of a clock, the goals of pronunciation teaching swung in the past from the Audiolingual Method extreme, which advocated explicit training in segmental phonetics towards accuracy based communication, (Richards and Rodgers 1990) to the early Communicative Approach extreme, which rejected the discrete-point approach as ineffective and proposed a more holistic, discourse-based view of language teaching whose successful outcome relied mainly on the instruction in suprasegmental features, including rhythm, stress and intonation. (Brumfit and Johnson 1979, Widdowson 1978). In other words, in their search for more effective pronunciation teaching and learning methods, linguists and language teaching specialists took a wide leap from the so-called bottom-up (i.e. from segments to suprasegments) to the top-down ( i.e. from suprasegments to segments) perspective.

Neither of those perspectives, however, turned out adequate and sufficient in teaching pronunciation for communication because, as Celce-Murcia ( 2004:10) claim, “both the inability to distinguish sounds that carry a high functional load ( list/least ) and an inability to distinguish suprasegmental features ( such as intonation and stress differences in yes/no and alternative questions) can have a negative on the oral communication – and the listening comprehension abilities – of nonnative speakers of English.” This has led to a revision of teaching goals and resulted in a more balanced or weak Communicative Language Teaching Approach, (Scrivener 2005). which is neither bottom-up or top-down, and it assumes that language is communication and the primary goal of teaching pronunciation is intelligibility that can be attained by attending to both segmental and suprasegmental aspects of phonetics.

The author of the present paper claims that despite the above mentioned importance and necessity to teach suprasegmental features, one of them, namely intonation, is given lower status and priority in pronunciation instruction in comparison with stress and rhythm, which may, therefore, affect negatively the learner’s ability to communicate successfully in English. It is thus my intention to examine the place intonation occupies in the balanced approach instruction, and see to what extent the currently employed methods and techniques of teaching intonation help to develop the speakers’ ability to communicate in English, both fluently and intelligibly.

To attain the above aims, I will first consider differing opinions which either justify or reject the need to teach intonation. Next, the functions of intonation will be analysed from the so-called pre-communicative or traditional and communicative perspectives. I will then examine which of those approaches prevail in contemporary ELT course book syllabuses.

Intonation is usually defined as “speech melody that consists of different tones” (Dalton & Seidlhofer 1994:44). In fact, however, intonation must not be understood as a melody in the musical sense, where a singer holds a given pitch for a time before moving to the next one. In the linguistic sense, “the pitch variation extends over single phonemes, sequences of phonemes and whole utterances.” (Underhill 2005:76). ‘As observed by Kelly (2003:86), “It is an aspect of language we are very sensitive to, but mostly at an unconscious level.”

The teaching of intonation is a controversial and problematic issue. The opinions whether it should or should not be taught differ greatly, which in turn leads to a confusion about the place of intonation in pronunciation syllabuses. Depending on a pronunciation teaching specialist, intonation is either considered vital and significant for intelligibility, or regarded as completely unimportant. There are those for whom it is both significant and insignificant at the same time.

Dalton and Seidlhofer (1994: 75), for example, stress the significance of intonation by saying: “(…) intonation is a crucial element of verbal interaction, and most authors of teachers’ handbooks and teaching materials agree on this.” Parallel to this, they note a severe disproportion in the amount of attention and practice given to the teaching of various aspects of phonetics, intonation included, where the latter “is usually given short shrift, or left out altogether”.

By contrast, Jenkins (2000), the author of the pronunciation model for English as an International Language, known as the Lingua Franca Core, in her attempt to decide which features of English pronunciation are indispensable for intelligibility in communication between non-native speakers of English, regards intonation as non-significant and maintains that it could be excluded from English pronunciation courses.

To make matters even more complicated, Kenworthy ( 1987: 19) argues that, “(…)it is important for intelligibility, because it is used to express intentions. A speaker can show that he or she is asking for information, or asking for confirmation, seeking agreement, or simply making a remark that is indisputable or ‘common knowledge’, through the intonation of the voice.(…). Only those who take an extremely narrow view of intelligibility can disregard the importance of intonation” . Nonetheless, when discussing the main causes that affect intelligibility and result in subsequent miscommunication, Kenworthy distinguishes between those aspects of pronunciation which are “vital for intelligibility, and as such are to be given a high priority in phonetic training, and those whose effect on intelligibility is of low value and as such can be given a low and/or optional priority.” In her opinion, intonation belongs to the low value category and can be left out, because, as she explains, (p.123),“(…) it is difficult to give priorities for intonation unless one is able to predict what kinds of conversational encounters the learners will be involved in.”

On top of the above, the teaching of intonation appears to be quite problematic and is done unwillingly, possibly due to such claims as the one by Underhill (2005: 75), who maintains that, (…) The teaching of intonation seems to have been characterized by an even greater uncertainty and lack of confidence than the other areas of practical phonology. We do not have a practical, workable, trustworthy system through which we can make intonation comprehensible to ourselves or to our learners. This may be due to the nature of intonation itself, that it is somehow less perceptible and less tangible than other areas of language.

To conclude, on the one hand, a language teacher is either discouraged from undertaking the effort to teach intonation, or she/he is told that this aspect of prosody can be neglected altogether as it does not affect intelligibility. On the other hand, intonation is admittedly considered an important part of prosody and as such it should constitute an element of language teaching syllabuses.

Descriptions of intonation differ in the way they account for its meaning, which can be linked to grammar, attitude or discourse, (Underhill 2005). Those linguists and pronunciation teaching specialists who believe in the importance of teaching intonation look at this phonetic issue from two perspectives. One is the pre-communicative or the traditional approach, while the other is the communicative, discourse-based approach. Following Collins and Mees (2003) intonation has four important linguistic functions:

- focusing function,

- grammatical function,

- attitudinal function,

- discourse function.

The traditional approach isolates only the first three functions, namely, focusing, grammatical and attitudinal. From this perspective, intonation tends to be taught in a de-contextualised form, mainly on the sentence level. Even though the attitudinal function did appear in a context of dialogues, they were artificially created , chiefly to illustrate the usage of a given attitudinal tone, and as such they lacked the features of real-life discourse.

Let us take a closer look at the componential elements of the traditional approach in order to assess their value in communication.

(1) The focusing function allows the speaker to manipulate the location of the nucleus in a sentence, which otherwise normally falls on the last element in the tone unit, and highlight a piece of information one considers important, for example:

Tom admired his new car. – not John

Tom admired his new car. – not hated it

Tom admired his new car. – not someone else’s

Tom admired his new car. – not the old one

Tom admired his new car. – neutral

In such cases, the sentence stress and the higher intonation pitch overlap.

When a speaker employs the focusing function, he or she gives prominence, or highlights a selected word in an tone unit. In such cases the semantic focus is marked by prosodic prominence to signal the known/ unknown or the old/ new dichotomy, as in:

A: ‘I’ve lost my WALLET’

B: ‘A LEATHER wallet?’

A: ‘Yes, a leather wallet with a TEN –POUND NOTE in it.’

where the NEW /UNKNOWN information is given additional stress or prominence, while the OLD/KNOWN information is left unstressed. The prominent element is uttered with a higher pitch while the lower pitch is reserved for non-focused elements. Additionally, the prominence pitch is uttered with a greater loudness of the voice.

Other instances of giving prominence are emphatic stress and contrastive stress as in I’ve ALWAYS liked beer. or It’s not BLACK, it’s BLUE. It seems that teaching the focusing function of intonation, and its known/unknown aspect is an important preliminary step to instruction in the discourse function, to be discussed later in this paper.

(2) The grammatical function of intonation draws attention to the grammatical/ syntactic relations within a sentence. It marks the boundaries of syntactic structures such as phrases or clauses, helps to prevent disambiguation, differentiates between statements, questions and question-tags. For instance, there is a relationship between the completion of the intonation contour and the corresponding completion of a grammatical phrase, which is indicated by the falling pitch. Also, the difference is signaled in the sentence structure between defining/non-defining clauses, where intonation marks the presence of the comma, with the falling pitch, as in: Tom likes poetry which is sentimental and Tom likes poetry, which is sentimental, or Tom gave me some cake which was sweet and Tom gave me some cake, which was sweet, (examples mine) can be misinterpreted if the comma is not signaled by the intonation. When written, a sentence such as ‘Tristram left directions for Isolde to follow. ’ remains ambiguous unless it is uttered with the correct intonation that will help make the meaning clear, whether Tristram wanted Isolde to follow HIM or the DIRECTIONS (Fromkin 1998:276). To disambiguate such sentences, it is enough to know which element of the sentence to stress or make more prominent, bearing in mind that the stress shift must trigger the high fall intonation contour. Thus, one can say: ‘Tristram left the directions for ISOLDE to follow.’ or ‘Tristram left the directions for Isolde to FOLLOW.’

Teaching the grammatical function of intonation is often problematic, however, since the situation is not so clear and systematic as far as affirmatives, negatives and questions are concerned. The general rule says that statements, commands and wh-questions in English have a falling intonation contour at the end, while the yes/no questions have a rising tone. The following table (Collins & Mees 2003: 129) demonstrates that certain types of English utterances have a generally recognized and accepted intonation pattern, with either falling or rising pitch. In some cases, however, it is possible to apply other pitch contours instead of the so called ‘default’ pattern, and thus it is difficult to formulate clear rules as to guide learners in their choice of intonation. Cases where a general principle is immediately followed by an exception to it will obviously be confusing to students.

| utterance type |

default pattern |

other patterns / other meaning |

| STATEMENTS

| fall |

(1) rise – to add non-finality or questioning

(2) rise-fall – to add non-finality with an implication of an additional but unspoken message

|

| COMMANDS |

fall |

rise – to turn command into request |

| WH-QUESTIONS |

fall |

rise – to add warmth and interest |

| YES / NO QUESTIONS |

rise |

fall – to turn questions into exclamations |

Table 1. Intonation contours for yes/no and wh-questions. The default and other patterns.

Despite a certain amount of difficulty involved in teaching the grammatical function of intonation, it clearly plays an important role in communication. The examples quoted above demonstrate that the erroneous employment of intonation contours in speech production can cause the interlocutor to be misled either in the recognition of the sentence type or in the interpretation of meaning of ambiguous sentences.

(3) In its attitudinal function, intonation is an indicator of a speaker’s attitude as it helps them to express their approach, emotion, or stance towards other speakers or a given situation. Thus, by changing the pitch of the voice, and producing different tones, a speaker may sound friendly, angry, soothing, encouraging; he or she may want to express reservation, interest or enthusiasm.

Teaching attitudinal intonation has received a lot of criticism as elusive and difficult to present in a way “that offers learners a set of rules from which they can make meaningful choices affecting their own production. (…) attitudes are difficult to recognize in ourselves, they are difficult to label objectively.” (Underhill 2005). Moreover, attitudes described as ‘impressed either favourably or unfavourably’, ‘lighter, more casual’, ‘concerned, reproachful, hurt’, ‘flat, even hostile’ or ‘brisk, business-like’ (Underhill 2005) present shades of meaning that can be difficult to grasp. Another area of difficulty lies in the fact that even though the meanings of tones are not directly grammatical, in many instances the grammatical and attitudinal intonation patterns overlap. Following Cruttenden (1994:243) ‘some attitudes are inherently more associated with questions; in particular, high rise, which often has a meaning of surprise, frequently marks an echo question.’ Moreover, one and the same tone can be used to express a variety of meanings, for example, a falling pitch can indicate that the speaker is either ‘matter-of-factly’, ‘disinterested’, ‘bored’ or ‘relieved’

( Kelly 2000).

On the other hand, it would be unreasonable to claim that learners should not be taught how to express their emotions or attitudes, such as joy, anger, happiness, boredom, disappointment, etc, by means of intonation. It seems that some use of the attitudinal function of intonation should be made in classroom practice, as suggested by Kelly (2000): “However teachers can do some useful work with relating intonation to attitude in the classroom in the same way as we did with grammar and intonation.” He suggests that the attitudinal or emotive intonation practice should be done on lexical phrases such as How do you do, How are you, See you later, See you soon, At last, Look on the bright side, Don’t get me wrong, or As for me, which are used in colloquial everyday language and constitute a major feature of English.

To sum up briefly, the pre-communicative approach to the teaching of intonation does not seem enough considering the fact that communication between people is not limited to the sentence level exclusively. The sentences which are uttered by interlocutors usually constitute a part of a larger whole, called discourse. That is why intonation should be analysed and practiced at the level of exchanges of utterances in conversations.

Let us now consider an alternative, discourse-based approach to intonation, known as the Discourse Intonation model, developed by Brazil. It became influential in English Language Teaching (ELT) in the mid 1980s and 1990s, both for teacher training (language awareness) and classroom practice (pronunciation). The analysis of discourse, understood as “any meaningful stretch of language” (Kelly 2000) takes into account the interactive and interpersonal nature of communication in which two interlocutors follow conventions of ‘turn-taking’ and other ways of maintaining a conversation such as clarification, shifting, avoidance and interruption. (Brown 1994) By analyzing intonation at the level of discourse it is possible to see how it conveys ideas and information, how it enables the interlocutors to signal what knowledge is shared and what is new/unknown between them. In the discourse approach intonation patterns are no longer limited to single sentences, single instances of grammar or attitude, but go beyond the sentence level so it is possible to observe what choices speakers make in real life exchanges of utterances, and how intonation functions in authentic contexts. It is thus possible to see how the speakers organize information and how pieces of information relate to each other in conversations.

Brazil’s discourse intonation is a system / a structure in which utterances are made up of tone units which, in turn, comprise one or two prominent syllables. The last prominent syllable is always tonic. If there are two, the first one is called onset.

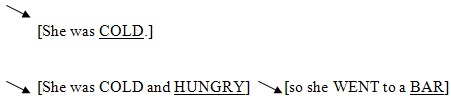

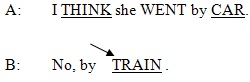

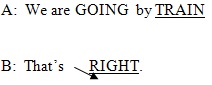

In the above examples, the tone units are enclosed in between brackets [ ]. Prominent syllables are indicated by the use of the upper-case letters The tonic syllable is underlined. It is important for a learner to identify the prominent syllable(s) in a tone unit. If there is only one prominent syllable, as in the first example, it is always tonic. If there are two, as in the other example, the pitch movement starts on the first (onset) and undergoes a significant change on the last (tonic). This change of pitch is perceived as a tone. The are five tones that speakers employ, namely fall, rise, fall-rise, rise-fall and level. In the above examples the falling tone is indicated by an arrow. The tone can be realized at a certain level, known as key, which is either high, mid or low, depending on what the speaker signals in his utterance in relation to what has been said. “The choice of key for any tone unit depends on the assumption one makes about the listener’s present view of things. High key attributes certain expectations to the listener and contradicts them. High key has contrastive implications: ‘not X ( as one might expect) but Y’ (Brazil 1994).

The use of low key, on the other hand attributes expectations and confirms them: “which you would naturally expect after Y”. (Brazil 1994:21)

The mid key can be said to attribute no expectation of this kind. (Brazil 1995:21). It is used to just add something to what has been said.

The key, whether high, mid or low, is relative to the speaker’s voice qualities and typical speaking habits. (Kelly 2000). In other words, the use of key is speaker-specific, what is a mid key to one speaker, can be a low or high key to another one.

Owing to the fact that discourse intonation deals with the moment to moment real life exchanges, much significance is placed on the amount of shared knowledge that exists between speakers during their exchanges. (Kelly 2000) This knowledge refers to how much speakers together know about a particular topic, how much meaning has already been established between them through negotiation, clarification, etc. Consequently, this knowledge will determine what type of tone they will adopt in order to convey meaning. “The basic tonal distinction in Brazil’s system is between fall and fall-rise.” (Cruttenden 1986) Thus, speakers can either use the proclaiming tone for the new/unknown information, additional to what is already shared, most frequently signaled by the falling tone, as in:

There is a cup of TEA in the picture. – used with the proclaiming tone, for NEW/UNKNOWN.

or the referring tone, most frequently signaled by the falling-rising tone for the information that already exists between them or is assumed as shared, as in:

The TEA is on the table. – used with the referring tone for the SHARED bit of information.

Additionally, there is the oblique tone, with the falling pitch, used when the language is being quoted, including rhymes, poems, multiplication tables, recipes, etc, so what the speaker communicates is just what is on the page, without attaching any meaning to it. Due to the fact that it has no direct communicative value (Underhill 2005), it will be disregarded in this paper.

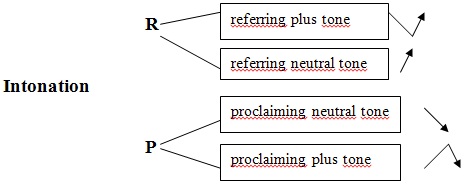

The proclaiming and referring, apart from their meaning discussed above, can be given an additional emotional value which is signaled by the change of the tone. Thus, the referring plus tone is conveyed by the rising tone while the proclaiming plus tone is marked by the rising- falling tone.

The following diagram (Underhill 2005) summarizes the choices that speakers can make in utterances, depending on the situation:

The advantages of teaching the discourse function of intonation over the grammatical and attitudinal ones are numerous. First of all, it is a reflection of language as used for communication between real speakers and in a real context, which is concomitant with the contemporary language teaching tendencies. As argued by Kelly (2003) “The analysis of intonation in spoken discourse gives a relatively straightforward way of describing and narrowing down a whole range of intonation possibilities. By concentrating on tonic syllables, and by showing an initial choice between referring and proclaiming tones, we divide those possibilities into two groups that can be analysed further.” In this way pronunciation teaching is systematic and governed by a set of rules that are clear and learnable. Unlike in the case of the attitudinal function, based on the 24 tunes which a learner is expected to memorize, usually with the help or artificial dialogues, then correctly interpret such indicators of attitude as ’mild pleasure’ or business-like’ or express attitudes, which may be alien to him or her, or cause embarrassment, (Kelly 2000) the discourse intonation is based on the speaker’s assessment of the state and extent of the shared knowledge between him and the listener and gives the speaker a simple binary choice of either referring – to what is common, or proclaiming – to what is new .

As has been demonstrated in the preceding section, a significant shift of focus in the approach to intonation has taken place. It is interesting to examine whether it is reflected in contemporary teaching materials. Towards this purpose, the following section of this paper will deal with the analysis of how much attention is devoted to the teaching of intonation in contemporary English classrooms, what is the scope of intonation practice, and finally which aspects of intonation tend to be most frequently taught. The results of research conducted by Szpyra-Kozłowska et.al.(2003) on a comprehensive sample of 20 Communicative Approach course books to determine which aspects of English phonetics are included in ELT syllabuses, show that intonation is, in fact, taught with attention given to its following aspects :

| Aspect of intonation |

number of course books |

- intonation in emotional statements

|

16 |

- intonation in emotional questions

|

13 |

- intonation in questions tags

|

12 |

- intonation in wh-questions

|

12 |

- intonation in neutral statements

|

12 |

- intonation in yes/no questions

|

11 |

- intonation in enumeration

|

33 |

- intonation in commands and exclamations

|

3 |

The conclusion which emerges from the analysis of the above list is that intonation tends to be approached by course book writers rather selectively. There is a visible bias towards practising primarily the grammatical and occasionally the attitudinal functions, with a stronger emphasis put on the grammatical role. Moreover, even though the syllabuses in the 20 course books reflect the teaching principles of the Communicative Approach, the intonation practice activities seem to lack the communicative purpose, due to the fact that intonational patterns are taught in a de-contextualized form, mainly on the sentence-level.

Among the ELT materials, the course book which is considered to be particularly useful in teaching pronunciation is New Headway Pronunciation Course, which is part of the New Headway English Course and can be used with the regular course book or separately. It is advertised as the phonetic instruction whose “aim is to help students to express themselves both clearly and confidently, by training them in the key areas of pronunciation, in particular the production of individual sounds, word and sentence stress and intonation”. (NHPC, 1999)

The close examination of the contents of the NHPC reveals that the ‘key areas’, with respect to intonation, are as follows:

Elementary level (NHPC 2002)

- intonation in questions, UP and DOWN tones ( single words)

- sounding polite – single words, short dialogues

- wh-questions – a single sentence level

- polite requests – a single sentence level

- sounding enthusiastic – question-answer utterances, enthusiasm limited to a single word ‘OK’

Pre-intermediate (NHPC 2001)

- sentence stress – sentence level

- difference between polite and impolite offers – short dialogues

- ‘OR’ questions – friendly or unfriendly intonation – short dialogues

- sentence stress for showing interest and surprise – two-sentence utterances

- corrective stress – focusing function on the sentence level

Intermediate (NHPC 2000)

- wh-questions – sentence level

- intonation in single words – a word level

- showing interest through short questions – two sentence utterances

- polite requests with ‘could’ and ‘would’ – two sentence utterances

- showing degrees of enthusiasm – two sentence utterances

- question tags with falling intonation – sentence level

- intonation with ‘really’ and ‘absolutely’ – two sentence utterances

- correcting politely – short dialogues, bearing elements of discourse such as “Well, actually…”

- rising and falling intonation in question tags – a sentence level

- showing disbelief with reported speech – sentence stress in two-sentence utterances

Upper-intermediate (NHPC 1999)

- hellos and goodbyes – singe phrase utterances

- exclamations – one sentence level

- rising and falling intonation in questions – single sentences

- wh-questions with rising intonation – short artificial dialogues

- special / contrastive stress – short dialogues

- sentence phrasing – defining and non-defining clauses – a sentence level

- exaggeration and understatement – sentence and dialogue level

- polite intonation in wh-questions – single sentence requests

- sentence stress –emphatic forms in short dialogues

The conclusion one may draw from the analysis of the above syllabus in terms of the focus and the nature of the exercises is very similar to the findings in Szpyra-Kozłowska et.al’s (2003) research. The following table demonstrates the proportional distribution of intonation practice activities in relation to the functions of intonation:

| Total number of activities |

Grammatical / Focusing function |

Attitudinal Function |

Discourse Function |

| 29 |

14 + 2 = 56% |

12 = 41% |

1= 3% |

Table 2. Proportional distribution of intonation teaching activities as related to

intonation function.

The amount of grammatically oriented intonation practice is overwhelming. Strikingly, the grammatical and the attitudinal functions dominate throughout the 4-level course. Very little attention is devoted to teaching the focusing and discourse functions.

It should be clarified that I am not trying to undermine the value of the grammatical and attitudinal functions of intonation, as they are of great significance for the clarity and precision of the intended message. Also, they may cause problems to learners because the rules for using intonation in statements, yes/no and wh-questions are not always very clear and systematic, and, as such, they need a lot of practicing. Still, in the majority of cases the grammatical and attitudinal intonation training is either done on a sentence or a short dialogue level, which does not seem enough. In a communicative course book, that naturally is supposed to advocate the principles of the balanced approach, one might expect at least some elements of the discourse function training at the intermediate and particularly at the upper-intermediate levels as the students’ linguistic and communicative competences are advanced enough to allow for such activities.

Teaching intonation should, in my opinion, consist of two stages, the first one, which is largely perceptive and imitative (based on the accurate reproduction of intonation patterns) and a subsequent perceptive / productive stage with a tendency towards the so-called immediate creativity, with focus on the discourse-based practice. Thus, in the early stages of language instruction the intonation training should be proportionally more imitative / reproductive, whereas in the latter stages of language teaching the activities should have a more productive, discourse-type character. Clearly, the focusing, grammatical and emotive functions lend themselves very well to be taught at the sentence level, and could thus constitute a major part of an intonation training syllabus at the early stages of pronunciation instruction. Gradually, with the development of students’ conversational skills, the syllabus should be expanded and elements of the discourse approach should be included in the intonation teaching process.

In this paper it has been argued that intonation, owing to its linguistic functions, can, to some extent, be responsible for the students’ level of success in communication. That is why, despite differing opinions that concern the justifiability of intonation teaching, this element of prosody should not be overlooked in foreign language instruction. The analysis of selected ELT course books has shown a visible bias towards teaching mainly the grammatical and attitudinal functions of intonation, with disregard for the discourse function. The lack of communicative, discourse oriented activities seems to clash with the contemporary communicative tendencies in foreign language teaching, which calls for a change in intonation teaching syllabuses by introducing and gradually increasing the amount of discourse intonation practice.

Bowler, B / Cunningham, S (1999) New Headway Pronunciation Course. Upper-Intermediate Level, Oxford: OUP

Bowler, B / Parminter, S (2001) New Headway Pronunciation Course. Pre-Intermediate Level, Oxford: OUP

Brazil, D (1994) Pronunciation for Advanced Learners of English, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, A (1992) Approaches to Pronunciation Teaching, London and Basingstoke: Macmillan Publishers Limited.

Brown, H.D (1994) Principles of Language Learning and Teaching, San Francisco State University.

Brumfit, C. / Johnson, K (eds.) (1979) “The Communicative approach to language teaching”, (w:) M. Celce-Murcia, D. Brinton, J. Goodwin, Teaching Pronunciation: A reference for Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (s. 10) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2004

Celce-Murcia, M / Brinton, D / Goodwin, J (2004) Teaching Pronunciation: A reference for Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Collins, B / Mees, I. M (2003) Practical Phonetics and Phonology, A resource book for students. London and New York: Routledge.

Cruttenden, A (1986) Intonation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crutenden, A (1994) Gimson’s Pronunciation of English, Arnold International Students’ Edition

Cunningham, S / Bowler, B (2000) New Headway Pronunciation Course. Intermediate Level, Oxford: OUP

Cunningham, S / Moor, P (2002) New Headway Pronunciation Course. Elementary Level, Oxford: OUP

Dalton, C / Seidlhofer, B (1994) Pronunciation, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Fromkin, V / Rodman, R (1998) An Introduction to Language, Harcourt Brace College Publishers.

Jenkins, J (2000) The Phonology of English as an International Language, Oxford: OUP.

Kelly, G (2000) How to Teach Pronunciation, Harlow: Pearson Education Limited

Kenworthy, J (1987) Teaching English Pronunciation, London and New York: Longman

Richards, C / Rodgers, T (1990) Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. A description and analysis, Cambridge: CUP

Scrivener, J (2005) Learning Teaching. Oxford: Macmillan Publishers Limited. s.39

Szpyra-Kozłowska, J / Nowacka, M / Bąk, L / Chaber, I / Święciński, R / (2003) „Priorytety w nauczaniu fonetyki języka angielskiego”, (in:) Sobkowiak, W. & E. Waniek-Klimczak (ed.) (2003) Dydaktyka fonetyki języka obcego III. Konferencja w Soczewce, 5-7.5.2003, (=Zeszyty Naukowe Państwowej Wyższej Szkoły Zawodowej w Płocku), Płock: Wydawnictwo PWSZ.

Underhill, A (2005) Sound Foundations. Learning and teaching pronunciation, Oxford: Macmillan Publishers Limited

Widdowson, H. (1978) "Teaching language as communication", (in:) M. Celce-Murcia, D. Brinton, J. Goodwin, Teaching Pronunciation: A reference for Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (s. 10) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2004

Please check the Pronunciation course at Pilgrims website.

|