Tolerance of Ambiguity and Its Implications For Reading

Ruben Cardenas Cabello, Peru

Rubén Cárdenas Cabello is an English teacher at USIL University in Lima, Peru. He is interested in developing tasks, approaches and activities to teach English as a foreign language. He has created a lot of materials and has run seminars in Peru. His current interests are how to teach grammar using pictures, and how to face ambiguity in classes while developing reading tasks.

E-mail: rubenteacherstalk@hotmail.com

Menu

Introduction

What is tolerance of ambiguity? Some quotes

Where does tolerance of ambiguity come from?

Tolerance of ambiguity in reading

Levels of tolerance of ambiguity

Levels of tolerance of ambiguity

Applications

Comments

Implications

Conclusions

Suggestions

References

Time has shown us that there are a lot of things that take place in our students’ minds when they are learning a new language, and what is more, they have to deal with the four skills: reading, writing, speaking and listening. For instance, we could see in a group of students of any level how some students easily grasp any explanation or application of a point but it happens too, that there are some students who could not grasp what the explanation was or what the use of a specific point was. However, these students are desperately trying to learn a new language; they always find lots of inexplicable things that interfere with their acquisition and therefore we see how they lose interest and endfailing exams and simply dropping out of courses. The main intention of this paper is to check how our EFL students deal with ambiguity, if they tolerate it or not, when they develop reading tasks in order to provide ideas and reflect on our teaching methods and strategies when having reading sessions in EFL classes.

Eherman says “Language learning for real communicative is an extremely demanding whole-person engagement. It requires the learner to cope with information gaps, unexpected language and situations, new cultural norms, and substantial uncertainty. It is highly interpersonal, which is in itself fraught with ambiguities and unpredictabilities. Language is composed of symbols, which are abstract and often hard to pin down. Concepts and expressions in any two languages do not relate one-to-one” (Ehrman, 1996). Given these complexities, it makes sense that tolerance of ambiguity is crucial to success in language learning aimed at a real communicative use. Students who lack tolerance of ambiguity tend to have a great deal of trouble in language learning, both formal and informal.

The learner makes discriminations, sets priority among competing concepts, and develops hierarchies in terms of level of abstraction. These activities usually entail integration of new information with the existing schema to change the latter and make something new,that did not exist before. “Jane Arnold with MadeleineEherman”

“The focus on affective variables in language learning is reflected in attempts to reduce anxiety and inhibitions and to enhance factors such as motivation and self-esteem. These factors are mostly dealt with in humanistic type of education.”De Andres(2002)

“Humanistic education is related to a concern for personal development, self-acceptance, and acceptance by others, in other words making students be more human. Humanistic education takes into consideration that learning is affected by how students feel about themselves. It is concerned with educating the whole person - the intellectual and the emotional dimensions.” Moskovitz (1978)

Owen and Sweeney (2000) note that Norton (1975) found evidence that psychologists have suggested eight distinct definitional categories for ambiguity which he includes in his definition of intolerance of ambiguity as “a tendency to perceive or interpret information marked by vague, incomplete, fragmented, multiple, probable, unstructured, uncertain, inconsistent, contrary, contradictory, or unclear meanings as actual or potential sources of psychological discomfort or threat” (Ely, 1995, p. 88). In general, “ambiguous situations may be marked by novelty, complexity, insolubility, and lack of structure” (Kazamia, 1999, p. 69).

The degree to which a person is cognitively willing to tolerate ideas and propositions that are against the persons own belief system or structure of knowledge marks the person’stolerance of ambiguity. A person who is tolerant of ambiguity may enjoy creative possibilities without being cognitively or affectively disturbed by ambiguity and uncertainty; so such a person can deal with uncertainty fairly comfortably, while a person who has a low tolerance may become anxious and frustrated when encountering a task with new, unknown elements that seem ambiguous or difficult (Hadley, 2003). According to Larsen-Freeman and Long (1991), people with low tolerance of ambiguity may experience frustration and diminished performance, may appeal to authority, for example to request a definition for every word of a passage, they may also prefer to categorize phenomena and tend to jump to conclusions. Budner (1962, cited in Johnson, 2001) states that ambiguous situations are sources of threat for those who are intolerant of ambiguity. In learning a second language, there are many occasions when apparently contradictory information is encountered such as words, structures and rules, even the culture.

Much has been written about this skill, mostly stating it is a passive skill. However, life and classroom experience has proved the opposite. We can say now, that it is a very active skill, since it makes the reader think and activate a lot of mechanisms in order to process information. Rebecca Oxford says that “ For the adult ESL learner, reading is a key to success in higher education. Without reading opportunities for understanding the

United States and achieving educational objectives are lost”. She also remarks that “reading competence does need grammatical competence, sociolinguistics competence, strategic competence and discourse competence.”

David Nunan says “Unlike speaking, reading is not something that every individual learns to do. An enormous amount of time, money, and effort is spent teaching reading in elementary and secondary schools around the world. In fact, it is probably true to say that more time is spent teaching reading than any other skill.” Taken from (Second Language Teaching & Learning, David Nunan1999, Page 249.)

Patricia Carrel and Joan C. Eisterhold mention that Goodman has described reading as a “psycholinguistic guessing game” (1967) in which the reader reconstructs, as best as he can, a message which has been encoded by a writer as a graphic display” (1971). Jeremy Harmer says that understanding a piece of discourse involves much more than just knowing the language. In order to make sense of any text we need to have pre-existent knowledge of the world (coo 1986:69). Such knowledge is often referred to as schema (plural schema). Each of us carries in our heads mental representations of typical situations that we come across. When we are stimulated by particular words, discourse patterns, or contexts, such schematic knowledge is activated and we are able to recognise what we see or hear because it fits into patterns that we already know.

When reading takes place in any class teachers may notice fast that something is going on our students’ minds. We can see it in their eyes and faces. To get more information about it let us read the following important information. “ what If in reading a sentence a reader finds something unfamiliar in lexical meaning or grammatical structures, the meaning of the written material may be ambiguous to him. Sometimes the context will help to clarify the meaning of an unfamiliar element, but often it won't. Understanding what is read involves not only the process of reasoning, but also the process of eliminating ambiguity. In this study of students' comprehension of sentence structure, it was found that many intermediate grade students (grades 5-8) had difficulty recognizing sentence transformations with equivalent meanings. They also had difficulty recognizing the kernel sentences of larger sentences. The study indicated that there was a wide range in the abilities of the students to recognize sentence transformation with equivalent meanings and kernel sentences of larger sentences. A teacher can help students increase their understanding of sentence structures by exploring with them the various ways in which the same concept can be stated. Teaching the equivalency of one structure to another can be used as a basic method of expanding students' understanding of the literal meaning of various types of sentence structures whether the structures are infrequentlyused, highly complicated, nonstandard, or ambiguous standard English sentences.

Ehrman (1996, 1999) considers three levels of function for tolerance of ambiguity; they include: 1. Intake, that is letting in the information into ones’ conceptual schema; 2. Tolerance of ambiguity proper which is the stage to deal with contradictions and incomplete information or constructs; and 3. Accommodation, that is integration of new information with existing schemata to make distinctions, set priorities, and restructure cognitive schemata. This third level is in its most effective state when the learner displays considerable tolerance of ambiguity and the capacity to cope with strong feelings provoked by experiences that seem to assault the person’s construal of the world and the self.

In language learning, in facing too much new information and contradiction, the learner is led to strong affective reactions, either positive or negative based on the success of the accommodation. In some cases, limiting cognitive capacity or setting up barriers to new input occurs. This in fact can be an affective source of certain thick boundary behavior. Ego boundaries which are flexible are related to tolerance of ambiguity in that they are associated with “disinhibition and potentially to openness to unconscious processes; they tend to promote empathy and the ability to take in another language and culture” (Ehrman, 1999, p.76).

Eherman notices “Tolerance of ambiguity is made of three levels”

- Intake (Letting it in)

- It permits information to enter to one’s conceptual schema in the first place; thick ego boundaries can interfere at this level (especially external ones)

- Tolerance of ambiguity:(Accepting contradictions and incomplete information)

- Intake has been successfully accomplished, necessitating that the learner deal with contradictions and incomplete information or incomplete constructs. This is often very difficult for thick-boundary learners.

- Accommodation: (Making distinctions, setting priorities, restructuring cognitive schemata)

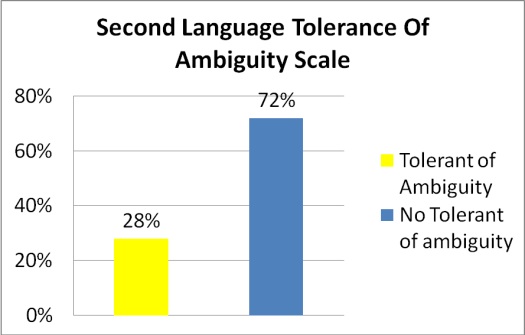

As I wanted to confirm the corresponding implications to tolerance of ambiguity, and its implications in reading. I decided to apply a questionnaire on ‘Second language Tolerance of Ambiguity Scale (by Christopher M Ely Department of English College of Sciences and Humanities Ball State University) to 25 students, age from 14 to 31. These students, who have been studying English at the Language Centre for more than 2 years in a 10 hour intensive course, are from different backgrounds and specialties. We have obtained the following results:

As we can see 72 % percent of students do not tolerate ambiguity when developing reading tasks in class. Which is, obviously, giving us a clear idea on what really happens when our students read texts. That is why, we see how students lose interest, and what is more, develop a kind of negative attitude when reading. We have also seen that students are desperately trying to use different strategies to get over these frustrating moments; for example, they stop reading to look up new words in order to understand or simply ask a classmate, interrupting, not only, the idea of the text but also the other student too.

According to the results obtained from the questionnaire ‘Second language Tolerance of Ambiguity Scale (by Christopher M Ely) We can say that our students do have problems at the moment of developing reading tasks in class and it’s the teachers’ role to look for new strategies and methods to make reading tasks much more meaningful.

A. Implications for EFL Teachers

EFL learners study English for different porpuses. Some will travel, others need it for their university studies, and a lot of students need it to have more opportunities at work. How it might implicate on the work of teachers in EFL classes? We can say that the kind of participants teachers have in class is totally multiplural. We mean that what students bring to the classroom is varied. For instance, some students have read a lot in their mother tongue, a lot of them haven’t read much, and a few students like reading. So the background students have is too little and it does not help them when reading, apart from that it is a trouble the vast vocabulary that the second language has.

So teachers roles in class is really challenging since they have to take into consideration a lot of aspects. And one simple thing is to know our students. I mean to get information about their studies, goals and learning styles.

B. Implications for Language Instruction

We should consider the following implications:

- Assess students’ background on reading. (mother tongue).

- Consider the multiplural realities.

- Choose and adapt reading strategies.

- Evaluate the use of other resources to help understanding while reading.

- Test students’ motivation for reading.

The results obtained above suggest that the majority of the students,72%, do not tolerate ambiguity when reading. And in terms of classroom practice, this work has the following implications.

- First, we must be aware of the little background our students have concerning to reading, which is why, they usually struggle.

- The well-known reading strategies seem not to solve students problems when reading.

- Luck of tolerance of ambiguity does create really trouble to learners when reading.

- Promote reading as much as possible.

- Assist learners when reading in order to know more about their ambiguity and be able to help them.

- Pilot new strategies and methods in order to lessen students ambiguity.

- Consider that reading is a really active skill, so that you must be ready to face students’ troubles.

Arnold Jane and Eherman Madeleine. 1999. Affect in Language Learning .

Pages . 68, 69, 74, 76, 78 and 84.

Scarcella Robin C. and Oxford and Rebecca L. 1992. The Tapestry of language learning, Page 93 .

Nunan David 1999. Second Language Teaching & Learning. Page 249.

Long H. Michael and Richards Jack C. 1987. Methodology in TESOL. Page 219.

Harmer Jeremy 2001. The practice of English Language Teaching. page 199.

Ely Christopher. 1995. Learning Styles in the ESL/EFL Classroom. Pages 87, 88, 89,90,91, 92, 93 and 94.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|