Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies Research Fund of 2015.

Scared to Speak: Underlying Elucidations that cause Communicative Anxiety among South Korean Tertiary EFL Students

Michael T. R. Madill, South Korea

Michael T. R. Madill is a Canadian who holds a Master of Science in Education (M.Sc.Ed.), a Diploma in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (Dip.TESOL), and is currently an Assistant Professor at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in Seoul, South Korea. He has presented his research publications at various international conferences over the last five years, with his current interests lying in reducing communicative anxiety in the language classroom and increasing English writing fluency. Email: mtmadill@hufs.ac.kr

Menu

Introduction

Literature review

Methodology

Results and analysis

Discussions and limitations

Conclusion

References

Appendices

When a student is learning English as a Foreign Language (EFL), they encounter many challenges and obstacles of varying levels of difficulty. These hindrances are very important in the learning process as the more we understand them, the better we are able to adjust our teaching methodologies to manage them.

One such problem is an increased level of communicative anxiety when producing the new language in the classroom. This Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety (FLCA) has essentially made students scared to speak, as they exhibit “…a type of shyness characterized by fear of or anxiety about communicating with people" (Horwitz, Horwitz & Cope, 1986, p.127). It has detrimental effects on speaking development and it is common to encounter students who exhibit varying levels of speaking anxiety during their language learning. For many, when they “…are confronted with a situation that they think will make them anxious, the most expected response is to avoid the situation and thus avoid the discomfort” (Kondo & Ying-Ling, 2004, p.259). As a result, the higher their intrinsic anxiety level, the less they will want to practice speaking English in class.

In the ideal language classroom, learners will be able actively identify the causes of their speaking anxiety and utilize learning strategies that effectively manage them. On the other hand, an effective educator will understand the challenges their language learners face and adapt their instructional approaches in order to minimize speaking anxiety levels. Thus, “we need to continue our efforts to identify the sources of anxiety, so that teachers will be able to prevent it, respond to it appropriately, and help students enjoy learning a Foreign Language (FL)” (Kitano, 2001, p.549). The more we know about the causes, the more we are able to manage and control it.

As a result, the following study will present two identified causes that are responsible for increased speaking anxiety levels among South Korean EFL students studying at the tertiary level. It is hoped that the findings will assist educators in creating an effective and anxiety-free classroom.

Communicative or speaking anxiety is "an individual’s level of fear or anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons" (McCroskey, 1977, p.78). To illustrate further, “anxiety interrupts behavior, focuses attention on what is being done wrong, and causes the person to seek another course of action” (Wong, 2009, p.4). In essence, when “…students are too scared to speak up in class, they can’t have any opportunities to practice and improve their oral skills” (Wong, 2009, p.4). Anxiety decreases opportunities to speak, which severely hinders the growth of communicative competence.

This problem is common in language classrooms because of a variety of societal, cultural, personal, and educational related variables, which vary throughout the world. This has a negative effect on learning as "there have been a number of studies in a number of instructional contexts with varying target languages which find a negative relationship between specific measures of language anxiety and language achievement" (Horwitz, 2001, p.115). It is a paralyzing worldwide problem that all language learners experience to varying degrees at some point in their development.

In the South Korean context, this is a problem because "...English is not a second language but a foreign language for Koreans. That is, there are few chances to speak English because English is not used frequently in daily life" (Seongja, 2008, p.376). The majority of university students in South Korea rarely have a need to use English outside the classroom as Korean is the predominant language used in day to day life.

To further impede their language development and add to their level of speaking anxiety, during high school in South Korea, all students prepare for their university entrance exam called the College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT). This very important examination requires only the receptive English skills of reading and listening while ignoring the productive aspects of speaking or writing. As a result, “this problem is exasperated as Korean students strive to merely memorize the specific English required to pass this language section in their College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT) during their final year of high school” (Madill, 2013, p.39). These students are not learning or developing productive speaking abilities, nor do not have the opportunity to practice this important skill outside of their classroom in their everyday lives. In essence, they are not effectively acquiring the language during their high school years, and are scared to speak when they must communicate in English conversational classes in university.

The need for English is also a problem as "the rise of foreign language requirements is occurring in conjunction with the increased emphasis on spontaneous speaking in the foreign language class" (Horwitz et al., 1986, p.131-132). It is well known in South Korea that "English speaking ability is connected directly to good jobs and good universities" (Mikio, 2008, p.387). This is the reality of English in South Korea, but unfortunately, these students do not develop productive English skills in their early years and are confronted with speaking anxiety when forced to use the language. To illustrate further, “… we need to devise more successful ways to make English education successful in Korea and most Koreans who lack the self-confidence in their English proficiency, feel confident in English abilities, so that Korea can gain the successful results for the enormous investment of time and money on English education” (Chang, 2010, p.132). FLCA is a very serious problem in South Korea and there are very few research reports that illustrate the complexities behind such apprehension in this specific context.

Before continuing, the work of Horwitz et al. (1986) in regard to their research into the concept of FLCA must be noted because it has revealed some important concepts. They explained that "since speaking in the target language seems to be the most threatening aspect of foreign language learning, the current emphasis on the development of communicative competence poses particularly great difficulties for the anxious student" (Horwitz et al., 1986, p.132). Their studies proved that "...the more anxious student tends to avoid attempting difficult or personal messages in the target language" (Horwitz et al., p.126). Although their research was very influential, it had its limitations because it was based on an English as a Second Language (ESL) environment where English is used in daily life. It is therefore important to explore how speaking anxiety is exhibited in an EFL context where the language is not commonly used outside the classroom. The reasoning is that in the South Korean context, “speaking and listening are considered to be the most difficult skills to make progress in because of the lack of opportunities to practice in a non-English speaking society. It is rare in both countries for a student to need to communicate in English in their daily lives” (Mikio, 2008, p.392).

We know that “learning a foreign language or L2 is therefore a psychologically unsettling process for students experiencing language anxiety” (Wong, 2009, p.3). This is due to the many different cultural, societal, and educational ideologies that are different in an Asian EFL context compared to an ESL environment. Thus, when an educator understands and acknowledges these causes of speaking anxiety in their EFL classroom, they can effectively tailor their teaching methodologies to minimize the anxiety levels. To illustrate this thought, "...teachers need to include a program that enables learners to start in a relatively comfortable and stress-free environment, and gives them the opportunity to learn in their preferred style" (Tasnimi, 2009, p.121). Furthermore, Horwitz, et al. (1986) effectively summarize this idea in the following way:

In general, educators have two options when dealing with anxious students: 1) they can help them learn to cope with the existing anxiety-provoking situation; or 2) they can make the learning context less stressful. But before either option is viable; the teacher must first acknowledge the existence of foreign language anxiety (p.131).

Understanding the causes of speaking anxiety leads to more effective language teaching methodologies and allows students to communicate in a comfortable learning environment. This is the goal, but it starts with the educator recognizing the problem, and developing solutions to minimize it.

The field of EFL speaking anxiety related to the language learning environment is an area that has not been extensively explored in the South Korean context. Therefore, this research will explain what is causing anxiety among these students using Horwitz et al. (1986) study as a basis for further development. It will add to the field of EFL speaking anxiety research by exposing the common causes of speaking anxiety among this unique group of English learners.

Research question

This study measured the underlying contextual elements that increase speaking anxiety levels in South Korean university classrooms that focus on conversational English. The main research question relates to the causes of speaking anxiety among South Korean EFL learners.

Context and participants

The subjects in this study were 82 university students studying at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies (HUFS) in Seoul, South Korea during the 2013 school year (N=82, 40 male, 42 female). Their age range was from 20 to 24 years old with the average being 21.6. Their academic majors varied widely from many different language specializations, business and economic concentrations, in addition to English literature majors. Of the total sample size, 39% were in their first year, 20% were in their second, 14% were in their third, and 26% were in their final year of study.

Their declared English levels were high intermediate to high advanced with their average TOEIC and TOEFL scores being 883 and 104 respectively. Most stated that they have been studying English for 7 to 10 years with 77% of respondents in this timeframe. The majority of the participants previously studied English in high school in addition to private language institutes or academies.

Measurements and testing instruments

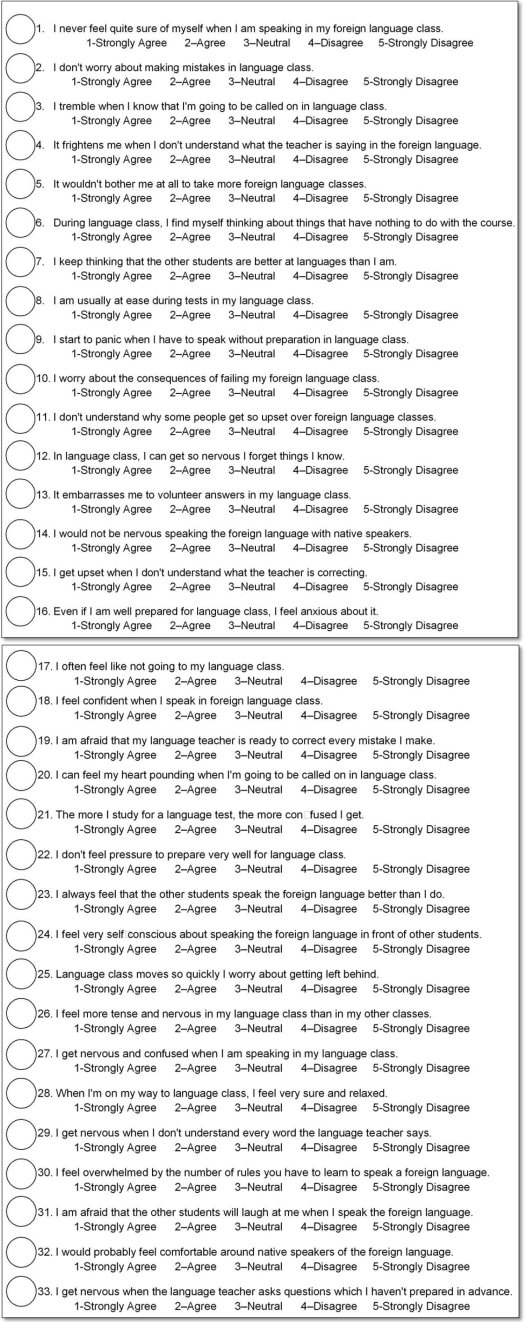

The current study employed two devices: a contextual survey modeled after the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS) developed by Horwitz et al. (1986), and individual, open ended interactive interviews with randomly selected students. The 33 question FLCAS survey (Appendix 1) was administered to explore the specific causes of English speaking anxiety, thus discovering what made them nervous in their EFL classroom. The answers were evaluated using a five-point Likert Scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree.

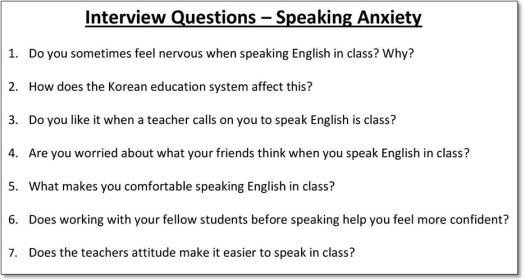

The individual interviews (Appendix 2) were conducted one-on-one with 15 students from various proficiency and fluency levels in an unoccupied classroom. Each student was questioned independently and the inquiries were intended to advance the understanding of the results gathered from the surveys. These discussions lasted roughly 15 minutes each, and all communication was recorded for further examination.

Research design and procedure

To test the main questions in this study, the process involved administering the survey followed by analyzing the data to identify the main themes contributing to their speaking anxiety. Once identified, the individual interviews were conducted in order to gain further insight into the main questions and themes uncovered from the surveys.

The results and analysis will be divided into two main classifications that were found to be common in this research. The first is a student derived source of speaking anxiety related to social and cultural variables. The second is an instructor induced source of apprehension in regard to adequate student preparation time and a fear of making mistakes in class.

Underlying social and cultural ideologies

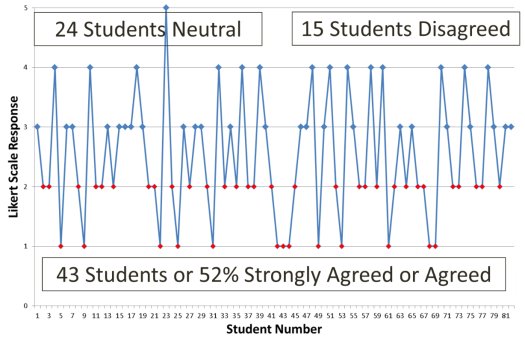

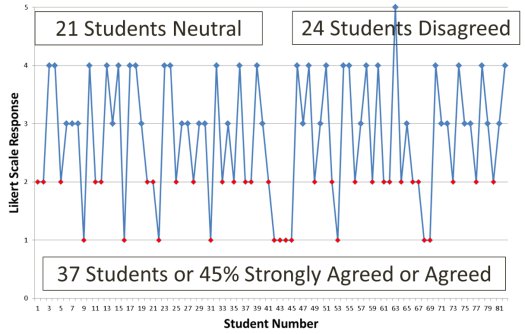

In general, the participants were not confident with their English speaking skills in the language classroom. This was confirmed in the results from question seven regarding the perception that other students were better at the language. It was found that 52% strongly agreed or agreed that they thought their classmates were more proficient in the language than they were (Appendix 4). Furthermore, this concept was identified in the data from question 23 regarding the feeling that other students in the class were better language speakers. The results for that question revealed that 45% strongly agreed or agreed to that statement (Appendix 5).

These social and cultural characteristics in regard to speaking anxiety not only surfaced in the survey, but also during the structured interviews. An astounding 87% of participants agreed that their social and cultural experiences have negatively affected their ability to confidently speak English in South Korean classrooms. The students admitted to having developed anxiety because of their intrinsic realization of the classroom atmosphere.

Being such a competitive educational environment, their self-confidence in speaking English was very low relative to the perception of their peers. They were frequently worried that other students would be more advanced. Many agreed during the interviews that they felt their English skills were inadequate compared to their classmates and they were unwilling to open up in the classroom and practice their English speaking. Wong (2009) effectively explains how speaking anxiety affects output where "if students are too scared to speak up in class, they can't have any opportunities to practice and improve their oral skills" (p. 4). This proved to be a major source of speaking anxiety in this study and one that is greatly hindering their overall speaking development.

Preparation time and fear of making mistakes

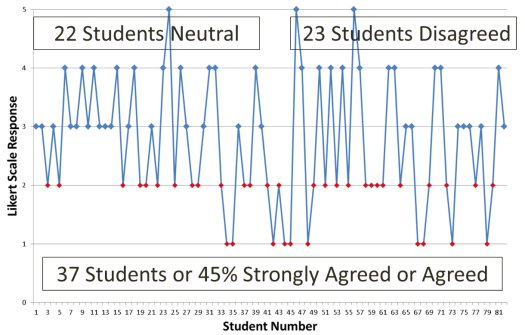

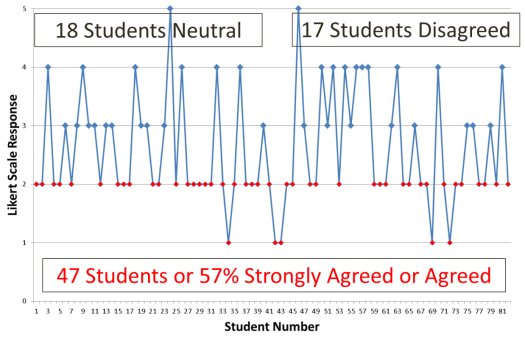

Another reoccurring theme was that without time to prepare, students commonly developed speaking anxiety in the language classroom. This was confirmed in question nine where 45% strongly agreed or agreed that they exhibit some form of anxiety when they have to speak before having time to prepare their response (Appendix 6). Furthermore, this was exhibited in the data from question 33 in reference to getting nervous when the teacher questions them before having adequate preparation time. This question resulted in 57% who strongly agreed or agreed that they got nervous without being provided adequate preparation time in the language classroom (Appendix 7).

During the interviews, this notion was expressed as 84% of the respondents explained how they became very anxious during class when the instructor would single them out or ask them a question before giving him or her time to prepare their answer.

Furthermore, the fear of making mistakes was a cause of anxiety that the majority of interviewees described as a major issue. This is similar to the findings of Horwitz et al. (1986) as "anxious students are afraid to make mistakes in the foreign language" (p.130). The participants explained that when they made a mistake in the classroom, they felt that this was an indication of their overall English ability. They expressed how they feared making mistakes in front of their classmates and teachers, which resulted in decreased self-confidence during classroom speaking activities and added to their overall anxiety levels.

Given such a small sample size, caution must be applied as the findings might not be applicable to all EFL classrooms. To explain further, some universities in South Korea require higher levels of English proficiency compared to competing postsecondary institutions. For example, places such as Seoul National University, Korea University, or Yonsei University, which are the top three post-secondary institutions in the country, require much higher English proficiency levels in order to be admitted, compared to lower tiered institutions. Thus, depending on the standing or level of university, the reasons for speaking anxiety may differ depending on how well the students can speak English. Institutions that demand more strict entrance requirements in regard to English proficiency may yield different results when it comes to speaking anxiety in South Korean EFL classrooms.

In reference to this study, the participants were enrolled at a university that would be considered somewhere in the middle when it comes to English language proficiency requirements for entering university in South Korea. Thus, to further this research, similar studies into varying levels of universities in South Korea would yield interested results.

In addition to this, there are varying levels of English abilities among students in South Korean university classrooms. Some students endured intensive English studies in their elementary and high school years. Thus, they are typically much more confident in their speaking abilities compared to students that did not receive this focused instruction. Surprisingly, some of the participants in this study indicated that they did not feel any speaking anxiety in the classroom because they felt that their English levels were much higher than other students in the class. In essence, they felt confident in the conversational English classroom compared to their other classmates with lower levels of speaking proficiency. These students were not common, but there were a few who felt this way and exhibited low levels of speaking anxiety.

On the other hand, some students had extreme levels of anxiety because they felt that their English was vastly inferior to others in the class. This is a common feeling as "anxious students also fear being less competent than other students or being negatively evaluated by them" (Horwitz et al., 1986, p.130). As a result, they commonly did not participate in classroom discussions or group activities and were essentially, scared to speak during conversational English class. In this study, this type of student was more common and they exhibited high levels of speaking anxiety during class activities.

Due to this variance in English abilities and university levels, these results need to be interpreted with caution and used as a generalization of the causes related to speaking anxiety in South Korean EFL classrooms.

All EFL students exhibit varying forms of communicative anxiety during their progression towards fluency. Thus, it is important that an educator understands the causes of communicative anxiety in their classrooms. To illustrate, "...we must recognize, cope with, and eventually overcome, debilitating foreign language anxiety as a factor shaping students' experiences in foreign language learning" (Horwitz et al., 1986, p.132). In addition, “it is not surprising that such a personal and ego-involving endeavor as language learning is the subject of feelings of anxiety, and it is important to understand how this anxiety functions in language learning” (Yan, & Horwitz, 2008, p.176). Therefore, an understanding of the underlying causes of speaking anxiety is an effective way to lower apprehension levels and develop learners’ self confidence in using the language. For students, identifying, understanding, and overcoming their causes of speaking apprehension will help them improve and become better English speakers.

This study provides two main categorizations of the causes of speaking anxiety among South Korean university level EFL students. These two issues were common among the majority of the participants in this study and were problems in the South Korean EFL classroom. It is hoped that this study will help educators better understand their learners and help students gain more confidence when speaking English.

Chang, B. (2010). Cultural identity in Korean English. Journal of Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics, 14(1), 131-145.

Horwitz, E. K. (2001). Language anxiety and achievement. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21(1), 112-127.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132.

Kitano, K. (2001). Anxiety in the college Japanese language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 85(4), 449-546.

Kondo, D. S., & Ying-Ling, Y. (2004). Strategies for coping with language anxiety: The case of students of English in Japan. ELT Journal, 58(3), 258-265.

Madill, M. T. R. (2013). The pragmatics of Korean university practical English composition: Current deficiencies, preferred genres, and effective learning strategies. International Journal of Foreign Studies, 6(2), 35-57.

McCroskey, J. C. (1977). Oral communication apprehension: A summary of recent theory and research. Human Communication Research, 4(1), 78–96.

Mikio, S. (2008). Development of primary English education and teacher training in Korea. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 34(4), 383-396.

Seongja, J. (2008). English education and teacher education in South Korea. Journal of Education for Teaching, 34(4), 371-381.

Tasnimi, M. (2009). Affective factors: Anxiety. Journal of Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics, 13(2), 117-124.

Wong, M. (2009). Language anxiety and motivation to learn English: A glimpse into the form 4 classroom. Paper presented at the UPALS International Conference on Languages, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED515046

Yan, J. X., & Horwitz, E. K. (2008). Learners’ perceptions of how anxiety interacts with personal and instructional factors to influence their achievement in English: A qualitative analysis of EFL learners in China. Language Learning, 58(1), 151-183.

Appendix 1: Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS)

Source: Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety.

The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132.

Appendix 2: Interview Questions

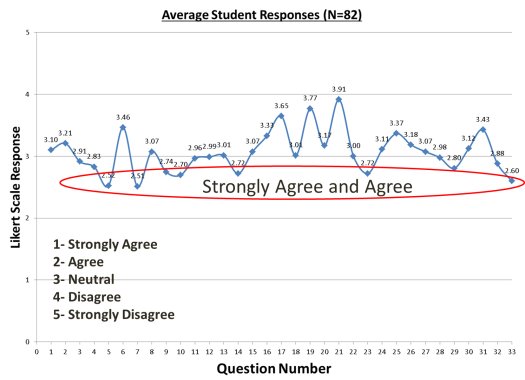

Appendix 3: Overall Results from the FLCAS

Appendix 4: Question 7 - Results

Appendix 5: Question 23 - Results

Appendix 6: Question 9 - Results

Appendix 7: Question 33 - Results

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|