An Evaluation of EFL Students’ Vocabulary Size and Their Textbooks: A Case Study of Vocational College Students in China

Feng Teng, China

Feng Teng is a language teacher educator at the department of English, Nanning University, China. He is interested in doing research on vocabulary studies, extensive reading and listening. His recent publications appeared in ELTWO and TESL Reporter Journal.

E-mail: tengfeng@uni.canberra.edu.au

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Literature review

Research questions

Methodology

Participants

Research instruments

Textbooks

Procedure

Results and discussion

Measuring vocabulary size

Measuring textbooks

Pedagogical implications

For teachers and learners

For material writers

Conclusion

Limitations

Future directions

References

Evaluating learners’ vocabulary size and their textbooks is of major importance to teaching English. Measurement of vocabulary size in this study was conducted with a vocabulary size test (Nation & Beglar, 2007). Data collected from the test scores revealed that the students from vocational colleges had a low vocabulary size. Input from the textbooks was analyzed by using the Range program (Heatley, Nation, & Coxhead, 2002). The results showed that learners who completed these series of textbooks would only encounter 1,020 of the most frequently used word families. This an indication that the textbooks which participants are using have no relationship to acquiring more vocabulary. Therefore, teachers, as well as material writers, should take students’ vocabulary size into account when editing textbooks. Using supplementary reading materials during instruction to increase learners’ vocabulary size can be beneficial to teaching. In addition, emphasis on word lists and frequently-used words are also recommended.

Research has consistently demonstrated that vocabulary knowledge contributes to reading comprehension (Nation & Snowling, 2004; Qian, 2002; Teng & He, 2015; Zhang & Annual, 2008), as well as listening and speaking (Nation, 2001). The breadth of vocabulary knowledge, also defined as vocabulary size (Qian, 1999), or the number of words that a learner possesses, is a dimension that needs further measurement. As stated in Laufer & Goldstein (2004), measuring vocabulary size has been shown to predict success in reading, writing, and other language proficiency skills, including academic achievement. In addition, measuring vocabulary size is important because it is related to the vocabulary demands of the textbooks that learners need to work on (Nguyen & Nation, 2011).

However, there is limited research on measuring Chinese EFL learners’ vocabulary size, particularly students from the three-year mode of vocational college with an aim of achieving a diploma. Therefore, in order to make our teaching creative, studies on these learners’ vocabulary size and their textbooks are of great significance. This will help guide teachers and textbook writers to understand the type of words that need to be incorporated into teaching materials.

Measuring vocabulary size

Measuring the breadth of vocabulary knowledge, or vocabulary size, is considered important, as it helps us understand the number of words that language learners know (Nation, 2001). As stated in Read (2000, p. 18), “Although the need to know learners’ vocabulary size might seem superficial, it can give a delineation of learners’ total vocabulary size than an in-depth probe of a limited number of words.” Much research has been conducted on measuring the vocabulary size of students learning English as a second language (L2) or a foreign language (EFL) (Fan, 2000, 2003; Webb, 2008).

In Fan’s (2000) study, she measured 138 first-year diploma students’ receptive vocabulary size. Her findings showed that EFL students were rather weak at the 3,000 and university word levels. Following this, Fan (2003) did a larger scale project measuring 1,067 first-year students in seven local institutions of Hong Kong, and found that these tertiary-level students needed help in learning academic vocabulary. Webb (2008) evaluated the receptive vocabulary size of 83 Japanese EFL learners by using a translation test. The receptive vocabulary size of the learners in his study was 73.52 out of 90. His study showed a relatively large vocabulary size of EFL students in Japan. However, a recent study conducted by Mclean et al. (2014) showed that EFL learners in Japan only had an average score of 3,715 word families. Concerning the research mentioned above, one thing that must be remembered is that participants from different educational levels might yield different test results (Schmitt, 2010). Thus, it is necessary to concentrate on measuring the vocabulary size of learners in a similar educational setting.

Evaluating textbooks

Recent research has shown that a void has occurred in traditional approaches to using textbooks. Eldridge & Neufeld (2009) evaluated the vocabulary profiling of the textbooks, and revealed that those textbooks were not appropriate for learners to improve their vocabulary. Cobb (2008) also analyzed over 375,000 running words in a series of books. His findings showed that learners did not have enough repeated exposure to the 3,000 level vocabularies after reading all the texts. Shin & Chon’s (2011) study indicated that the textbooks in secondary schools in Korea contained word lists as large as 7,430. This is larger than the 3,000 words required by the National curriculum. Thus it would be difficult for students to acquire new words using only textbooks. Similar results were also found by O’Loughlin (2012). He analyzed three levels of the course book series, New English File, and discovered that there were quite a number of words in the textbooks that appeared to be very difficult for EFL learners. Thus, he proposed that after learning these texts, learners could not acquire enough frequent words. Likewise, Webb & Macalister (2013) also proposed that the lexical load of the textbooks written for L1 children is as large as the textbooks written for adult learners. Thus neither of these two kinds of textbooks are suitable for L2 reading.

The research mentioned above seems to propose that current English textbooks are not adequate for teaching, and that adding supplementary reading materials is necessary. As stated in Lessard-Clouston (2013, p.21), “Textbooks seldom address vocabulary sufficiently.” Hence, more research on measuring the vocabulary load of the textbooks is needed, especially for learners with limited proficiency levels.

Proposition of deficiency in literatures

Literature conducted to date is limited in at least two ways: First, the research was conducted mostly on advanced university learners. More findings need to be done to determine the vocabulary size of EFL learners in vocational colleges. Secondly, research conducted to date focused on learner’s vocabulary size as a separate entity from textbooks. The link between vocabulary size and their English textbooks was lacking. This is of great significance, because as Lessard-Clouston (2013, p.16) stated, “Learners will benefit if they spend time learning materials that are appropriate to their levels.”

Overall, the present study attempted to answer the following questions:

- What is the vocabulary size for the vocational college students?

- How is the vocabulary load of the textbooks used in vocational colleges?

- Are the English textbooks used by vocational college students up to expectation?

With the help of the directors in charge of the college English departments from three vocational colleges in the Guangxi region (Guangxi Vocational College, Nanning Vocational College, and Guangxi Finance Vocational College), 3,105 participants from different majors were involved in the current study. Studying in vocational colleges in China generally last for three years; with the aim of achieving a non-degree diploma. The majors are all vocation-oriented, e.g., interior design, automobile maintenance, computer maintenance, etc. Admission into a vocational college is open to students of all levels; even those with low English proficiency.

Initially, there were 3,400 participants. The scores of 295 participants were not included because 150 participants dropped out of the process and 145 participants did not answer it carefully (i.e. most of them chose the option I don’t know). Their scores had a large standard deviation (beyond 7.69) from the mean.

Vocabulary size test (VST)

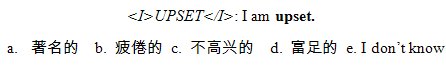

The present study measured participants’ vocabulary size by using Nation & Beglar’s (2007) vocabulary size test, a proficiency measurement tool for understanding L2 or EFL learners’ total vocabulary size. The frequency levels were based on Bauer & Nation (1993). The word frequency lists in this test were developed from British National Corpus (Nation & Webb, 2011). Beglar (2010) examined the validity of this test, purporting that the items in it were unambiguous; thus making it reliable for measuring L2 or EFL learners’ total vocabulary size. This mainly measures decontextualized knowledge of the word, although a single non-defining context is provided. As shown in the following example below:

UPSET: I am upset.

a. famous b. tired c. unhappy d. rich; we notice that the option that matches the word upset is c. There are two versions of this test: monolingual and bilingual. In considering vocational college students’ limited language proficiency, the present study used the 14,000 bilingual version. The test contained 140 multiple-choice items, with 10 items from each 1,000 word family level. A test-taker’s total vocabulary size can be measured when multiplying by 100. Therefore, if a learner scores 36 out of 140 on the test, their total vocabulary size are 3,600 word families. For the computerized and paper test, the present study used the online test (available at http://my.vocabularysize.com). It is assumed that students who took the paper test would be more likely to avoid answering some of the difficult items. In addition, it would be more convenient for calculating scores and conducting statistic analysis through a computerized test.

Range

Heatley, Nation, & Coxhead’s (2002) Range program was used to evaluate the coverage of participants’ English textbooks by certain word lists. This program is applied successfully in many previous studies (e.g., Chung & Nation, 2003; Li & Qian, 2010).

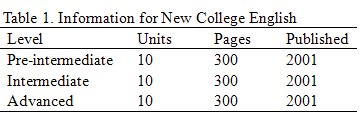

New College English (Li, 2001), which is one of the mainstream textbooks for tertiary-level English education in China, is used by students in three of the above mentioned vocational colleges. It is highly regarded by teachers within the EFL teaching profession in China due to the fact that it aligns itself with the requirement of national curriculum for college students (M.O.E., 2007).

These textbooks contain three levels: pre-intermediate, intermediate, and advanced level. Each level contains 10 units, which are divided into five separate sections. The first two sections of each unit include listening, a passage and post-reading exercises, which are twelve pages long. The next two sections, include another passage, post-reading exercises and practical writing, which is twelve pages in length. Post-reading exercises focus on reading comprehension, grammar, vocabulary, translation, speaking and writing. Furthermore, at the back of each unit there is a special section titled culture salon, which presents additional reading materials. The following is a description of what is contained in the textbooks.

The VST was completed from May to June 2014. Although Nation & Beglar (2007) suggested that it is better to administer the test on a one-on-one basis, it is quite difficult to administer using the suggested method. Therefore, three parallel classes in each university were arranged in three computer classrooms to finish the test at the same time. The average time for completing the test was 50 minutes. One class consisted of approximately 50 students. Thus, about 150 students in each university took the test at the same time. Due to some factors such as the vacancy of the classrooms and the availability of students and their instructors, the time for finishing the VST lasted for 6 weeks.

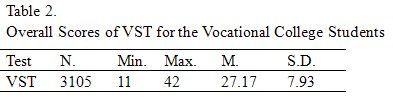

The mean scores and standard deviation of VST administered for the vocational college EFL first-year students are presented in Table 2.

As can be seen, the mean score of the VST was 27.17, while the standard deviation was 7.93. This indicated that there was a variance in the overall results of the VST. The overall receptive vocabulary size for the vocational college students was relatively low considering the fact that the data calculated a total of 140 items. The vocabulary size of the vocational college students was 2,717 word families, which is relatively low. It was calculated by multiplying the raw scores to 100 and it amounted to 14,000 total.

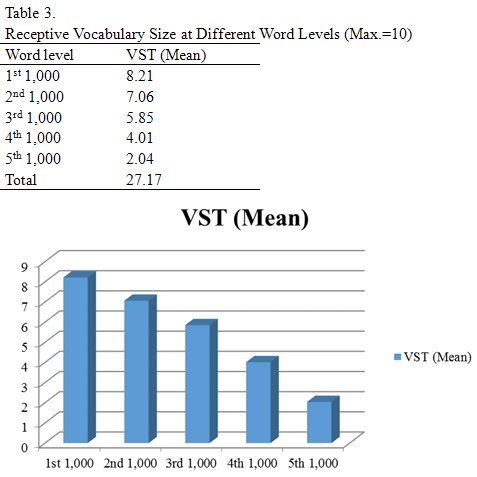

However, it is essential to provide details on the receptive vocabulary size of each word level because the calculated percentage based on mean scores cannot be overgeneralized to each word level. Details on vocabulary size at different word levels are presented in Table 3. Figure 1 present the same results graphically.

Figure 1. Overall Mean Scores for VST at Different Word Levels (Max.=10)

Looking at the table above, the mean scores of VST show a steadily diminishing trend. This is an indication that words at the lower frequency level are more difficult for the learners. Similar results were found by Webb (2008). His study showed that learners’ receptive knowledge decreased as the frequency of the words decreased. Unexpected results arose at the 5,000-5,900 word level, for which vocational college students could only answer few words correctly.

In answering the first question concerning vocational college students’ vocabulary size, the first response is that vocational college EFL learners presented a relatively low vocabulary size. Secondly, learners seemed to have higher scores for the words that appeared more frequently. This indicated that the learners were more proficient at learning the most frequently-used words. It was difficult for them to understand words at the low-frequency level correctly.

This result might be related to vocational college students’ word levels. High school students were more willing to enter a university rather than a vocational college in China (i.e., they only choose a vocational college when they don’t have another choice). Vocational college students also received English instruction in China where they were trained to swiftly notice the embedded clues in the multiple-choice English test. Thus their English vocabulary size was relatively low.

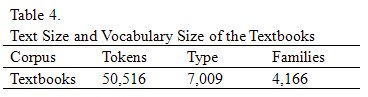

New College English are the textbooks used in measuring the present study. The publisher’s permission was obtained for scanning the textbooks and compiling them into a computer database. The textbooks’ length (the number of tokens), the number of types, and the number of word families are presented in Table 4.

As shown in Table 4, the tokens are 50,516. This means the amount of running words in the textbooks are 50,516 in number. Included are 4,166 word families. A word family is the base word plus its inflected and derived forms (Bauer & Nation, 1993).

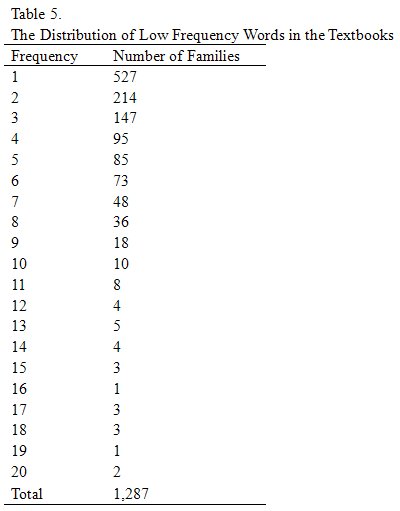

The number of low frequency words occurring once, twice, etc., up to twenty times in this corpora are presented in Table 5.

It is clear from Table 5 that, overall, 1,287 out of 4,166 families occurred from one to twenty times, thus indicating that learners working their way through these series of textbooks would continually encounter quite a number of words that they would never see again or would only see a few times.

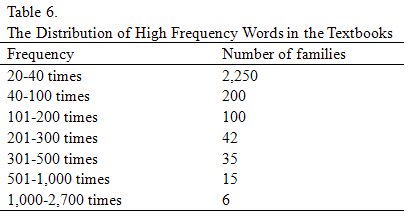

The number of high frequency words occurring 20-40 times, 40-100 times, etc., up to 1,000 times in this corpora are presented in Table 6.

As shown in Table 6, learners would benefit from encountering a number of words more than 20 times in the textbooks. However, there were seldom word families from 200 frequency level up.

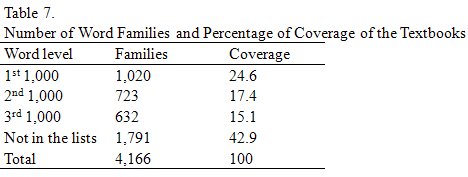

The coverage of the first, second, and third thousand are presented in Table 7.

Table 7 showed that knowing the 1st and 2nd 1,000 word families could only account for 42% of word families in the textbooks. The word families not included in the frequently-used lists accounted for 42.9%.

The second question is on the vocabulary load in the textbooks. It appears that textbooks contained up to 42.9% of infrequently-used word families, but the most used words (which are expected to be included in textbooks), accounted for less than 50%. In addition, a number of words appeared less than 20 times. This made it unlikely for the learners to acquire vocabulary from textbooks (Pellicer- Sa´nchez & Schmitt, 2010; Pigada & Schmitt, 2006; Teng, 2014a). There were 632 word families from the third 3,000 word level, which is the academic word list (AWL). Words from this list are the words for the students who wanted to further their academic studies (Coxhead, 2000). These words provide useful coverage for newspapers (Nation, 2006). This might be the source from which the textbooks were adapted.

Combining data in Tables 2 and 3, to answer the third question whether textbooks are suitable for vocational college students or not, the answer seems to be clear. The vocabulary load of the textbooks seemed to be too heavy. Since the learners only had an average vocabulary size of 2,717, and very few students had acquired words beyond the 4,000 level, the textbooks appeared to be too difficult for them. The following are selected from the words that are presented in the textbooks, but beyond the frequently-used word lists (wobble, wanly, congenial, animosity, vicarious, backlash, caprice, belch, incur, tumble, untenable, chronological, tantrum, tumultuous, sturdy, contrition, squashy, stainless, fertility). It is assumed that reading a textbook that contains a lot of infrequently-used words, might cause learners with limited proficiency level to lose interest in reading. The selection of words in the textbooks seemed not to be in conformity with the principles on word frequency. Learners have to spend a great deal of time learning many infrequently-used words that are seldom or not repeated in the entire series of textbooks.

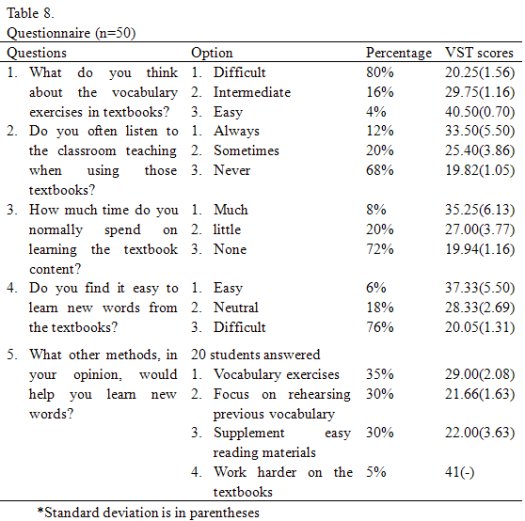

In order to demonstrate the link between VST and textbook appropriateness, a sub-sample of 50 students were required to answer a questionnaire (see Table 8).

Table 8 includes the questionnaire. It showed that only a few students with a relatively large vocabulary size regarded the word-focused exercises in the textbooks easy (Question 1). It also portrayed the fact that students who spent time and effort studying the textbooks had a relatively large vocabulary (Questions 2 and 3). A large percentage of students who regarded this method ineffective in learning new words from the textbooks seemingly had a small vocabulary (Question 4). Question 5 asked for further suggestions to enhance learning new words. Most of the students recommended word-focused activities, rehearsal of frequently-used words, and supplementing easy reading materials. Few of them suggested using textbooks as learning tools.

Overall, data from the questionnaire showed the validity of VST, as well as a link between given VST level scores and textbook appropriateness. Most vocational college students had a relatively small vocabulary size, and only a few of them who had a large vocabulary size regarded textbooks as a source for acquiring vocabulary. These results appear to have important pedagogical implications on teachers, learners, as well as textbook writers.

The importance of students’ motivation can be seen in Gardner (2006), where students with high degree of motivation performed better than those with low motivation. When a learner is motivated, he/she has the desire to conduct relevant activities. However, the large number of low-frequency words in the textbooks may deprive them of the motivation to learn English. Even if some learners made efforts in finishing these series of textbooks, they would only be exposed to only 1,020 frequently-used word families. As stated in Zimmerman & Schmitt, 2005, p.165), “The benefit to the student is well worth whatever costs are accrued in teaching high-frequency words.” Thus, the teacher should choose frequent, relevant words to teach. Based on the above findings, English teachers should encourage learners to focus on the use of word lists, such as New General Service List (NGSL) (Browne, 2013), as well as intentionally learn some word usage. This will ensure learners become exposed to more frequently-used words. For example, emphasis on the 2,000 words from the NGSL is suitable for the participants with a low-intermediate vocabulary size in the current study. As stated in Schmitt (2010, p. 19), “Learning vocabulary is incremental in terms of acquiring an adequate vocabulary size.” Thus it is important for students to have some active vocabulary learning strategies (e.g., word cards (Nation & Meara, 2010) or the keyword method (Sagarra & Alba, 2006), both on their own or after class.

Teachers should also notice that expecting their learners to learn a large number of significant words from textbooks is not reliable. Therefore, utilizing research-based information and supplemental reading materials for students is recommended. For example, graded readers are found to be useful to learners with limited vocabulary because they provide opportunities to encounter repeatedly frequently-used words in a variety of contexts (Schmitt, 2008, Teng, 2014b).

As stated in Schmitt (2008, 2010), material writers deliver useful research-based information to teachers as well as learners. There are a lot of vocabulary research outcomes that can be used for material writers. For example, there are some programs (e.g., vocabprofile and Textlex compare) that can be used freely from the website (http://www.lextutor.ca/), and OGTE, a free text analysis tool, from the website (www.er-central.com/ogte/). Textbooks should be analyzed by these programs. Thus high-frequency words are covered. Developing learners’ knowledge of high-frequency words is important (Browne, 2003). Concurrent with these developments in vocabulary, material writers should be in a position to incorporate learners’ lexical needs into textbook editing. For example, how many words should students in different educational levels be familiar with? How are these words sequenced, and what aspects of the word that learners focus on?

Textbooks need to systematically cover high-frequency words and academic words while developing learners’ critical thinking skills. Some textbooks, such as In Focus (Browne, Culligan, & Phillips, 2013), have been found useful. The textbooks provides a lexical syllabus comprising of the most high-frequency vocabulary. Following this, learners’ critical thinking skills and lexical strategy use will be improved. The words in the textbooks were selected from NGSL and AWL. These word lists are beneficial for learners, because the lists are focused on the frequently-used words. Including those word lists, and special attention on deliberate learning of those words, will make a textbook more inclusive and successful.

The findings in the current study suggested that vocational college EFL learners in the Guangxi Region had a limited vocabulary size. The textbooks that they used contained a large amount of low frequency words, which were not appropriate for them. Therefore, in teaching or contriving reading materials, teachers as well as materials writers should take students’ vocabulary size into consideration. Some pedagogical suggestions were proposed, such as supplementing some reading materials, and modeling active vocabulary learning strategies, direct learning of some important word lists.

This case study of vocational college EFL students resulted in a dilemma on choosing the appropriate reading materials to teach EFL learners with a limited vocabulary. However, we should be mindful that the results should not be overgeneralized to university students, since they seem to have better English proficiency. In an ideal situation, the study will include more participants from different educational levels and also use a wide range of textbooks.

This study has wide implications for material writers and teachers who teach English to vocational college students. Other textbooks can be analyzed, which may provide more in-depth insights on how high-frequency words or low-frequency words are presented in textbooks. In addition, there are other vocabulary size tests, such as the vocabulary levels test (Schmitt, Schmitt, & Clapham, 2001) and the X-Lex and Y-Lex vocabulary size tests (Meara & Milton, 2003). Future studies on comparing the results of using different tests are recommended.

Bauer, L., & Nation, I. S. P. (1993). Word families. International Journal of Lexicography, 6(4), 253-279.

Beglar, D. (2010). A Rasch-based validation of the Vocabulary Size Test. Language Testing, 27(1), 101-118.

Browne, C. (2003). To Push or Not to Push: A vocabulary research Question. Aoyama Ronshu, Aoyama Gakuin University Press. Achieved Oct 1st, 2014 from

http://www.charlie-browne.com/downloads-links/

Browne, C. (2013). The new general service list: Cerebrating 60 years of vocabulary learning. The Language Teacher, 37 (4), 13-16.

Browne, C., Culligan, B., & Philips, J. (2013). In focus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chung, T., & Nation, I.S.P. (2003). Technical vocabulary in specialised texts. Reading in a Foreign Language 15(2), 103-116.

Cobb, T. (2008). What the reading rate research does not show: Response to McQuillan & Krashen. Language Learning & Technology, 12 (1), 109-114.

Coxhead, A. (2000). A new academic word list. TESOL Quarterly, 34(2), 213-38.

Eldridge, J., & Neufeld, S. (2009). The graded reader is dead, long live the electronic reader. The Reading Matrix, 9 (2), 224-244.

Fan, M. Y. (2000). How big is the gap and how to narrow it? An investigation into the active and passive vocabulary knowledge of L2 learners. RELC Journal, 31,105-119.

Fan, M.Y. (2003). Frequency of Use, Perceived Usefulness, and Actual Usefulness of Second Language Vocabulary Strategies: A Study of Hong Kong Learners. The Modern Language Journal, 87(2), 222-241.

Gardner, R. (2006). The socio-educational model of second language acquisition: A research paradigm. EUROSLA Yearbook, 6, 237–260.

Heatley, A., Nation, I.S.P., & Coxhead, A. (2002). RANGE and FREQUENCY programs. Retrieved October 1st, 2014 at

http://www.vuw.ac.nz/lals/staff/Paul_Nation

Laufer, B., & Goldstein, Z. (2004). Testing vocabulary knowledge: Size, strength, and computer adaptiveness. Language Learning, 53(3), 399-436.

Laufer, B., & Nation, I. S. P. (1999). A vocabulary size test of controlled productive ability. Language Testing, 16, 36-55.

Lessard-Clouston, M. (2013). Teaching vocabulary. Alexandria, VA: TESOL International Association.

Li. Y.H. (2001). New College English. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

Li, Y. Y., & Qian, D. D. (2010). Profiling the Academic Word List (AWL) in a financial corpus. System, 38, 402-411.

McLean, S., Hogg, N., & Kramer, B. (2014). Estimations of Japanese university learners’ English vocabulary size using the vocabulary size test. Vocabulary Learning and Instruction, 3(2), 47-55.

Meara, P. M. & J. L. Milton (2003). The Swansea Vocabulary Levels Test: The Manual. Newbury, UK: Express Publishing.

M.O.E. (2007). Curriculum requirement for teaching college English. Ministry of Education of People’s Republic of China. Retrieved Oct.10th, 2014 from

http://www.moe.edu.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/s3857/201011/xxgk_110825.html

Nation, I. S. P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nation, I.S.P. (2006). How large a vocabulary is needed for reading and listening? The Canadian Modern Language Review, 63(1), 59-82.

Nation, I.S.P., & Beglar, D. (2007). A vocabulary size test. The Language Teacher, 31(7), 9-13.

Nation, I.S.P., & Meara, P. (2010). Vocabulary. In N. Schmitt (Ed.), An introduction to applied linguistics (2nd ed., pp. 252-267). London, England: Hodder Education.

Nation, I.S.P., & Webb, S. (2011). Researching and Analyzing Vocabulary. Boston, MA: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Nation, K, & Snowling, M. J. (2004). Beyond phonological skills: Broader language skills contribute to the development of reading. Journal of Research in Reading, 27, 342-356.

Nguyen, L.T.C., & Nation, I.S.P. (2011). A bilingual vocabulary size test of English for Vietnamese learners. RELC Journal, 42(1), 86-99.

O’Loughlin, R. (2012). Turning in to vocabulary frequency in course books. RELC Journal, 43(2), 255-269.

Pellicer- Sa´nchez, A., & Schmitt, N. (2010). Incidental vocabulary acquisition from an authentic novel: Do things fall apart? Reading in a Foreign Language, 22(01), 31-55.

Pigada, M., & Schmitt, N. (2006). Vocabulary acquisition from extensive reading: A case study. Reading in a Foreign Language, 18(1), 1–28.

Qian, D. D. (1999). Assessing the roles of depth and breadth of vocabulary knowledge in reading comprehension. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 56, 282-308.

Qian, D. D. (2002). Investigating the relationship between vocabulary knowledge and academic reading performance: an assessment perspective. Language Learning, 52(3), 513-36.

Read, J. (2000). Assessing vocabulary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sagarra, N., & Alba, M. (2006). The key is in the keyword: L2 learning vocabulary learning methods with beginning learners of Spanish. The Modern Language Journal, 90(2), 228-243. DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2006.00394.x

Schmitt, N. (2008). Review article: Instructed second language vocabulary learning. Language Teaching Research, 12(3), 329-63.

Schmitt, N. (2010). Researching vocabulary: A vocabulary research manual. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Schmitt, N., Schmitt, D., & Clapham, C. (2001). Developing and exploring the behavior of two new versions of the vocabulary levels test. Language Testing, 18 (1), 55-88.

Shin, D., & Chon, Y. V. (2011). A corpus-based analysis of curriculum-based elementary and secondary English textbooks. Multimedia-Assisted Language Learning, 14(1), 149-175.

Teng, F. (2014a). Incidental vocabulary learning by assessing frequency of word occurrence in a graded reader: Love or Money. LEARN Journal, 7(2), 36-50.

Teng, F. (2014b). Vocabulary growth for low-proficiency students through reading graded readers. Paper presented at the 1st TRI-ELE International Conference, Bangkok, Thailand.

Teng, F., & He, F. (2015). Towards effective reading instruction for Chinese EFL students: Perceptions and practices of lexical inferencing. The English Teacher, 44(2), 56-73

Webb, S. (2008). Receptive and productive vocabulary sizes of L2 learners. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 30, 79-95.

Webb, S., & Macalister, J. (2013). Is text written for children useful for L2 extensive reading? TESOL Quarterly, 47 (2), 300-22.

Zhang, L. J., & Anual, S. B. (2008). The role of vocabulary in reading comprehension: The case of secondary school students learning English in Singapore. RELC Journal, 39(1), 51-76.

Zimmerman, C.B., & Schmitt, N. (2005). Lexical questions to guide the teaching and learning of words. The CATESOL Journal, 17, 164-170.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|