The Effects of Teaching Critical Thinking on EFL Learners’ Listening Comprehension

Mansor Fahim, Sadegh Shariati, and Zahra Masoumpanah, Iran

Dr. Mansor Fahim is an associate professor of TEFL at Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Iran.

Sadegh Shariati is a Ph.D. Candidate at Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran. He is also an instructor of TEFL at Farhangiyan University, Khorramabad, Iran.

E-mail: shariati1352@yahoo.com

Zahrah Masoumpanah is currently a Ph.D student. She is also an instructor of TEFL at Farhangiyan University, Khorramabad, Iran. Email: Zmasoumpanah1356@yahoo.com

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Review of related literature

Research questions

Null hypothesis

Methodology

Data analysis

Results and discussion

Conclusion

References

This study was an attempt to investigate the effects of teaching critical thinking skills on listening comprehension ability of EFL learners. For this purpose, two intact classes, each consisting of 16 males and females (N.32) took part in this study. They were similar in educational background, studying American Headway 4 at Zabansara Institute in Khorramabad. They had already studied American Headway, starter, 1,2,3 and were at intermediate level of English proficiency based on the rankings of the books. After assigning the two intact groups to experimental and control groups, the researcher taught critical thinking techniques to the students in the experimental group for three sessions while the students in control group were following their regular class schedule. After the training sessions, the subjects in the two groups were administered four listening comprehension tests each of which was followed by five multiple-choice questions. Two independent t-tests were run to compare the mean scores of the two groups. The findings revealed that those students who received instruction on critical thinking skills did better on the listening comprehension tests. It was also observed that within the experimental group, there was not any significant difference between the performances of male and female Iranian EFL learners’ listening comprehension ability.

Critical thinking, according to Schafersman (1991), means correct thinking in the pursuit of relevant and reliable knowledge about the world. A person who thinks critically can ask appropriate questions, gather relevant information, efficiently and creatively sort through this information, reason logically from this information, and come to reliable and trustworthy conclusions about the world that enable one to live and act successfully in it. He continued to say that all education must involve not only ‘what to think’, but also ‘how to think’. In most educational systems, as Paul (1990) believes, students gain lower order learning which is associative, and rote memorization resulting in misunderstanding, prejudice, and discouragement in which students develop techniques for short term memorization and performance. These techniques block the students' thinking seriously about what they learn. Fisher (2003) emphasizes the significance of teaching critical thinking skills. He contends that critical thinking skills are required to be taught since students' thinking skills are not enough to face the problems students deal with either in education or in daily life. Therefore, educators are required to focus on teaching critical thinking to inform them how to learn instead of just transmitting information that is what to say.

A few studies have been conducted so far to throw some light on the importance of critical thinking on language learning. Richards and Schmidt (2010) state that in language teaching, “critical thinking is said to engage students more actively with materials in the target language, encourage a deeper processing of it, and show respect for students as independent thinkers”(p.147 ). Villavicencio (2011) studied critical thinking in relation to achievements, reported that critical thinking significantly correlate with learners’ proficiency. Kamali and Fahim (2011) reported a significant relationship between critical thinking and reading abilities of learners. To them, critical thinking construct is a strong predicator of learners' achievements. Fahim and Komijani (2010) conducted a research to identify any significant relationship between critical thinking ability and L2 vocabulary knowledge. The results revealed that Iranian EFL learners’ vocabulary knowledge was significantly related to their critical thinking ability. In another study, Fahim, Bagherkazemi, and Alemi, (2010) investigated the relationship between eighty-three EFL advanced learners’ performances on the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal and the reading module of TOEFL. The researchers found that learners‘ scores on the reading test increased significantly with their scores on the WGCTA. Facione (1992) and Paul (2004) also suggests there is a significant correlation between critical thinking and reading comprehension. In the same line, a study by Malmir and Shoorcheh (2012) revealed that students who received instruction on critical thinking strategies did better on the speaking ability.

Although a few studies have been conducted on the effects of teaching critical thinking on reading comprehension and speaking ability, no studies have been done to examine the effects of teaching critical thinking on listening comprehension. To shed more light on this issue, the researcher embarked on the task of investigating the impact of teaching critical thinking skills on EFL learners’ listening comprehension.

This study intended to answer the following questions:

Q1. Does teaching critical thinking skills have any significant effect on the development of listening comprehension of Iranian EFL learners?

Q2. Does teaching critical thinking skills affect male and female learners differently?

The above questions lead to the following null research hypotheses:

H01. Teaching critical thinking skills has no significant effect on the listening comprehension of Iranian EFL learners.

H02. Teaching critical thinking skills does not affect male and female language learners differently.

Subjects

Two intact classes, each consisting of 16 males and females ( 32) took part in this study. They were similar in educational background, studying American Headway 4 authored by John and Liz Soars Published by Oxford University Press at Zabansara Institute in Khoramabad. They had already studied American Headway, starter, 1,2,3 and were at intermediate level of English proficiency based on the rankings of the books. The classes were randomly assigned to control and experimental classes, each group consisting of 16 people. There were 8 male and 8 female learners in each group. The learners were between 16 and 28 years of age.

Instruments

Four intermediate listening comprehension tests each of which followed by five multiple-choice questions were used as the main instrument in this study.

Critical thinking training

In the experimental class, the researcher taught teaching critical thinking techniques to the students for three sessions. In the first session, the teacher explicitly explained what critical thinking is and how significant it is to have a critical mind in modern life. Then, during the following sessions the teacher taught critical thinking techniques for about 60 minutes and gave them time to practice these skills. These skills include involving learners in problem solving activities, raising questions, teaching logical reasoning, evaluating others’ arguments, etc. Everything was the same for the control and experimental group except for this treatment (critical thinking treatment).

Procedure

After assigning the two intact groups to experimental and control groups, the researcher taught critical thinking techniques to the students in the experimental group for three sessions while the students in control group were following their regular class schedule. After the training sessions, the subjects in the two groups were administered four listening comprehension tests each of which was followed by five multiple-choice questions.

After scoring the test, the results were analyzed statistically to evaluate some relationships (if any) between teaching critical thinking techniques and students’ performance on listening comprehension. Two independent t-tests were conducted to answer the two questions posed at the outset of the research.

An independent t-test (tables 1, 2) was conducted to compare the scores of experimental and control groups. There was a significant difference in scores for experimental group (M= 16.75, SD=1.00) and control (M= 15.25, SD= 1.18). The magnitude of the differences in the means was very large.

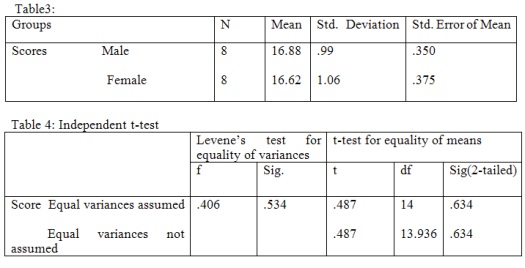

Another independent t-test (tables 3,4) was conducted to compare the experimental group scores for males and females. There was no significant difference in scores for males (M= 16.88, SD=.99) and females ( M=16.62, SD=1.06). The magnitude of the differences in the means was very small.

The first and main question of this study is to check if teaching critical thinking help EFL learners improve their listening comprehension. As we can see in Table 1, the mean score for the experimental group is 16.75 and the mean score for the control group is 15.25. Thus, there is an apparent difference between the performances of the two groups in favor of the experimental group. But in order to check if such a difference is statistically significant or not an independent T-test was used. There results of the used independent test have been presented in the table 2. The obtained t value is 3.87. This value is greater than the critical value for t with 15degrees of freedom at .05 level of significance. Therefore, the first null hypothesis of the study is rejected and it can be concluded that the experimental group has outperformed the control group. Accordingly, it can be concluded that teaching critical thinking has been effective in improving Iranian EFL learners’ listening comprehension.

The second research question of this study is to check if teaching critical thinking skills affect male and female learners’ listening comprehension differently? In order to answer this question, the results for the performances of female and male Iranian EFL learners in the experimental group were compared with each other using an independent T-test. As we can see in table 3, the mean score for females is 16.62 and the mean score for males is 16.88. Thus, there is not a significant difference (0.26) between the performances of the two groups. In order to check if such a difference is statistically significant or not, an independent T-test was used. As we can see in table 4, the obtained value is .48. This value is smaller than the critical value for t with 14 degrees of freedom at .05 level of significance. Because this value is less than the critical value for t, the second null hypothesis of the study is accepted and it can be said that there is not any significant difference between the performances of males vs. females.

The findings of the present study showed that experimental group outperformed the control group. That is, the students who received instruction on critical thinking did better in listening comprehension . Therefore, it can be concluded that critical thinking training had a crucial impact on improving listening comprehension of Iranian EFL learners. In addition, the findings of this study also showed that within the experimental group there was not any significant difference between the performances of male and female Iranian EFL learners’ listening comprehension ability.

The result of the study can motivate the syllabus and material designers to include critical thinking issues both in students' text books and in teacher training courses. Learners are in need of text books that invoke their critical thinking and teachers need to be trained to change their attitudes toward students and themselves.

Facione, P. A. (1992). Critical Thinking: What it is and why it counts. Retrieved from

http://insightassessment.com/t.html

Fahim, M., Bagherkazemi, M., & Alemi, M. (2010). The relationship between test takers’ critical thinking ability and their performance on the reading section of TOEFL. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 1 (6), 830-837.

Fahim, M., Komijani, A. (2010). Critical thinking ability, vocabulary knowledge, and L2 vocabulary learning strategies. Journal of English Studies, 1 (1), 23-38.

Fisher, A. (2003). An introduction to critical thinking. Retrieved from

www.amazon.com/critical thinking-Alec- Fisher/dp/0521100984

Malmir, A.,& Shoorcheh, S. (2012). An investigation of the impact of teaching critical thinking on the Iranian EFL learners’ speaking skills. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 3(4), 608-612.

Paul, R. (2004). The state of critical thinking today: The need for a substantive concept of critical thinking. Retrieved from

www.criticalthinking.org

Richards, J. C.,& Schmidt, S. (2010). Longman dictionary of language teaching and applied linguistics. London: Longman.

Schafersman, S. D. (1991). An introduction to critical thinking. Retrieved from

www.freeinquiry.com/criticalthinking.html

Villavicencio, F. T. (2011). Critical thinking, negative academic emotions, and achievement: A meditational analysis. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 20(1), 118-126.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English Language Improvement for Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

|