Making Early Language Learning Effective

Mija Selič, Slovenia

Mija Selič is a teacher, teacher trainer and executive assistant to the CEO at C00lSch00l private language school. She is an innovator in finding new ways of teaching and in developing teaching materials for very young language learners. E-mail: mija.selic@gmail.com

Menu

What is the main result of language learning?

A global approach to young language learning

Vocabulary taken from a context

Vocabulary used in a context

Vocabulary is memorised creatively

Cross-curricular focus

A practical example of an approach covering all of the points mentioned above

To sum up

Refernces

The obvious answer is knowledge of a particular language, but can we define exactly what language knowledge is?

If we focus the answer on children, more precisely, on young children (age 5-10) who learn a foreign language, the answer should be easier. According to the syllabuses in various textbooks and workbooks for young learners, knowledge of a foreign language at this age usually focuses on learning basic vocabulary connected to topics that are familiar to young children, such as family, toys, hobbies, food, colours, animals, etc.

There is, however, more to knowledge than the simple fact of knowing these basic words. In order for the words to be of any use to us, and to the people we communicate with, we need the words to make sense in both conveying and receiving the message. We should, therefore, agree that not only knowing the words but also being able to use them in communication is the main reason for language learning.

Many may say: ‘Don’t bother with communication at this early age. It will be on the menu later in higher grades. Children need to know the words first.’

But is this really the case? Should we really separate knowing words from using them?

If there is one person who really needs to make sense of learning, in order to be ‘involved’ and ‘motivated’, I believe it is the child. You can explain to the adult that some ‘out of context’ words will come in useful later in time, and he/she will patiently try, keep listening and memorise the words. The child, however, will not. In my twenty years of practice, it has become clear that the child needs to see the sense in what he/she is doing at the present time, or else his/her interest is quickly lost. The child does not care what might happen ten years from now.

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, the word ‘global’ means something relating to the whole world. Furthermore, Global Education is understood as education connected with people around the world (Global Education Guide, 2009). The way I understand a ‘global approach’, however, is that it is a way of learning ‘as a whole’, where everything is connected and makes sense. It is actually related to ‘global reading’, which is understanding the basic meaning of a text without focusing on details (Wambach and Wambach, 1999).

In order to make young language learning effective, children need to find some purpose in it. In my understanding, this means that the lessons need to have a context. I would call this a global approach, which means:

- vocabulary is taken from a context;

- vocabulary is used in a context;

- vocabulary is memorised creatively;

- the focus of learning is cross-curricular.

What we need to ask ourselves at this point is what a context actually is for a young child. Does opening a textbook with the topic ‘my family’ (or any other topic, for that matter) create sense for a child?

If we imagine a child at home (in a natural environment) immersed in the mother tongue, what can we see? There is a child playing games with his/her friends, family, toys or pets. There is a parent reading a story to his/her child. There are children digging a hole in the ground in search of treasure. There is a group of girls playing the role of mothers and their children, and so on and so on. All of these provide a context for a child because he/she finds sense in the actions he/she is involved in. And for that, I believe, no textbook is needed.

Let us now try to tailor the afore mentioned contexts to a lesson for young language learners. In order to create a ‘natural-like environment’, stories, games and a bunch of children are needed. Knowing that it is a lesson at school, we are obliged to follow the curriculum and its aims. Learning new vocabulary, oral practicing, learning grammar, listening exercises, etc. should therefore be incorporated into the learning process.

There are many fairy tales and stories that cover all of the topics one can think of. A lot of them are picture books that are perfectly suited to the early language learning classroom. Pictures, I have found, are essential in a narrative young foreign language approach, because they provide visual support to audio input. Apart from creating a context, storytelling is also a way of establishing the authenticity of the learning environment, simply because it is something children are used to in their everyday life. It gives them a home-like feeling, and therefore a feeling of security.

Once children feel secure and comfortable, the learning process can be effectively established (Marjanovič Umek, 2004). The teacher chooses the story bearing in mind the cross-curricular focus and the curriculum aim(s). Some picture books can cover variety of topics, from science to art and everything between, whereas others can be used specifically for one topic. Some practical ideas about storytelling are described in the handbook ‘Tell it Again!’, published by the British Council.

Why do we believe it is important for a child to have a context for learning new words, grammar, or whatever? Because the memory works better if you can relate new information to a context that makes sense to the learner. If the person is emotionally involved as well, it makes learning even more effective (Beyer, 1992).

Let us say that the context has already been established and the vocabulary is taken from it. In order to memorise new words, children need to practise them. Again, the most effective way is to put the practice in a context, preferably one in which children are also emotionally involved. The easiest way is to turn the activity into a game. In order to do this, we need to set some rules: how to play, how to score, how to cooperate and what determines the winner. We also need to establish what is inacceptable and what the consequences of breaking the rules are. After the initial try-out, the activity becomes an enjoyable event. Games can involve the whole class or can be performed with smaller groups. For young children, pairs are the most effective way of cooperation (Johnson and Johnson, 1987). I use quite a wide range of game-like activities in my classes, where young children can effectively use their limited knowledge of foreign language words in oral practice. Certain types of teaching aids that provide visual support can be very useful in such activities.

Many authors have created diagrams presenting the most efficient ways to memorise things. The percentages vary among the authors, but the tendency is more or less the same. According to Kagan and Kagan (2009), reading is at the bottom: only 10% of what we read is memorised. The percentage increases with hearing and seeing (20%), and with a demonstration 30% of the knowledge is memorised. However, when the matter is discussed we learn 50%, and this increases to 90% if we tell and explain things to others.

In other words, in order to memorise effectively a wide range of senses and skills need to be employed.

No matter which topic is discussed, it can be incorporated into almost any subject area. For example, if we discuss ‘food’, the lesson can be designed as research to determine where a certain kind of vegetable or fruit is grown, which at the same time covers the area of geography. It can also venture into mathematics, by trying to compare the children’s likes and dislikes regarding food and then presenting the results in a diagram. We could provide many similar examples. It should be emphasised that all of this is derived from a simple picture book! In the child’s mind, all of the subject areas are suddenly entwined. In short, everything is global.

The continuation describes my typical approach when opening a new topic (project).

In order to engage young children in learning, we first need to establish both the right atmosphere and the context. Storytelling is perfect for this. Prior to reading, some activities can be carried out to ‘set the scene’ and prepare the children for listening. Let us say that the story The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle is chosen.

The first step is setting the atmosphere, introducing the characters and preparing the children for listening through so-called ‘listening discrimination’ (Wambach and Wambach, 1999). In order to do this, four different sounds are performed using a tambourine and bells, and each sound is associated with a different act or object: flying, crawling, an egg and a cocoon (for example, the sound of the bells represents flying). When the various sounds are performed during the activity, the children perform the correct movement or figure according to the sound they hear. There is no need to explain the meaning of the movements and figures when the activity is carried out for the first time. The aim at this stage is for the children to pay attention to the sounds and distinguish the difference between them. They will discover the connection to the story in the follow-up activities.

Illustrations 1 and 2 – The ‘listening discrimination’ activity.

The second step is storytelling. It is a good idea to find a cosy spot for storytelling, where all of the participants can sit comfortably. The teacher makes sure that eye contact can be established with every child. The story should be told fluently, with some additional acting performance and a lot of visual support. The sounds from ‘listening discrimination’ can also be incorporated. The picture book itself provides brilliant illustrations. However, to make the story even more interesting, some additional cards can be used to engage the children and ensure their active participation. These illustrated cards are also the basis for later activities that facilitate learning vocabulary, grammar or speaking practice. The teacher can repeat the listening discrimination activity after the storytelling, this time with the action being accompanied by oral and visual support, using the pictures from the cards mentioned above. Alternatively, the children can act the story out, and the caterpillar can ‘eat’ the food from the ‘cards’.

Illustration 3 – Storytelling: the children get visual and audio input at the same time. If the ‘listening discrimination’ activity is added, kinaesthetic types are also addressed.

In terms of a global approach, the words from the story are taken from a context in which the children are emotionally involved, and they make sense to them. Therefore, the words have a perfect basis for more effective memorisation.

Step three involves selecting the target vocabulary. If the story is told without illustrated cards, the words can be introduced in a follow-up activity. Firstly, an illustration from the book is shown and the children name the objects in it. As they name them, the children take turns in finding the words in a so-called Picture Dictionary, which is actually a flat fabric house. There are two types of Picture Dictionary: one is called the Cool Alphabet House (CAH) and the other is the Cool Theme House (CTH) (Illustration 4 and CoolHouses). The windows of the houses are turned into pockets in which illustrated cards are stored. In the CAH, the words are kept alphabetically. For example, the words that start with the letter ‘B’ are kept in the ‘B’ pocket. If, however, the child does not know the first letter of the word, he/she has two options: either the teacher shows the first letter on the illustrated card (which the teacher also holds in his/her hands) and pronounces it, or the child can search for the card in the CTH, where the words are stored thematically. For example, the word ‘pear’ is kept in the pocket ‘fruit’. By setting some rules, the activity can be turned into a game.

Illustration 4 – The so-called ‘Picture Dictionary’ in the shape of two houses.

Illustration 5 – Searching for the correct word in the Cool Alphabet House.

The activity itself helps children to group the words into categories, which is a known approach in an effective and creative way of memorising words (Beyer, 1992). Furthermore, it provides some practice for becoming familiar with the connection between pronunciation and transcription, and is therefore a pre-reading and pre-writing activity.

Follow-up activities can be organised in different ways to achieve specific aims, such as: (1) socialisation, (2) cooperation, (3) learning the target vocabulary, (4) personal pronouns (5), pre-reading and pre-writing, and (6) the verb ‘have’.

The type of card on which the picture and the matching word are on the same side (Illustration 4) is used for a brain-gym-like activity, where the children say the words (sentences) while rhythmically clapping and tapping with their hands (Illustration 7 and Card Game). Sentences are formed in such a way that they match the rhythm. This game is great for practising grammar and vocabulary. Again, the activity is turned into a game.

Another type of card is used for a cooperative card game in which the children pair up and ask each other questions (Illustration 8 and Card Game). Each card has a picture on one side and the matching word on the other. There are several piles of cards. Each pair chooses a pile and plays a cooperative card game. The pairs can leave the pile when they have ‘learned’ all of the words in the pile through a set of prearranged tasks. The game is played for 10 minutes, and then the pairs count how many words they have learned. The game can also be upgraded in such a way that the teacher can check how well the words have been learned.

Illustration 6 – An illustrated card type ‘A’

Illustration 7 – The brain-gym-like activity

Illustration 8 – A cooperative card game

Using another type of illustrated card, where the picture and the matching word are on two separate cards, the children can play different versions of a ‘memory game’, while at the same time practising the vocabulary. When they match the word with the illustration they also learn to read.

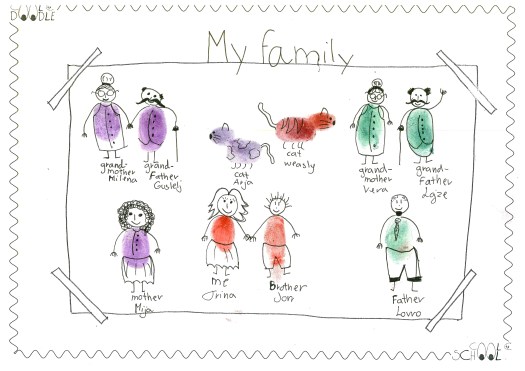

Additionally, there are pre-reading and pre-writing activities that can be carried out with the help of the doodles (CoolDoodle). Doodles are partly finished illustrations that the children complete by drawing, sticking, gluing or colouring, later adding words, sentences or groups of words next to the matching picture (Illustrations 9, 10). Both of the houses with illustrated cards are a great help during such tasks because they assist children with spelling (Illustration 11).

Illustrations 9 and 10 – The CoolDoodles ‘My Family’ and ‘The Weather’.

Illustration 11 – Writing with the help of an illustrated card.

The described approach has proven in practice to be a very effective way of both teaching and learning. Children learn fast because they are motivated. When they reach the age of nine, they are already prepared for some real grammar. By the time they are eleven, they are already consciously aware of and can use plural, some modal verbs (can, must) and the verbs ‘be’ and ‘have’, as well as being familiar with the basic use of articles. Furthermore, they are aware of time relations (past, present and future) and know that verbs change according to the time of happening. They also know the time adverbs that determine past, present or future actions. Moreover, they become familiar with word order (subject – verb – the rest) and are also acquainted with writing a structured text. Believe it or not, all of this is achieved through narrative and the games based on the above described illustrated cards together with the Picture Dictionary.

A global approach based on activities facilitated with the teaching aids presented above and wrapped in communicative didactics together with narrative has been very effective in my teaching practice over the last ten years. In order to bring the approach closer to teachers who teach young learners, a three-day seminar is held several times per year. Teachers have accepted the approach enthusiastically and the seminar itself is an enjoyable event. You can see it for yourself on Seminars. At present, the locations of the seminars are in Slovenia. This, of course, does not mean they cannot be organised elsewhere. For details contact info@c00lsch00l.eu.

Beyer, G. (1992) Urjenje spomina in koncentracije. Ljubljana: DZS.

Ellis, G., Brewster, J. (2014). Tell it Again! The Storytelling Handbook for Primary English Language Teachers. British Council.

Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R.T. (1987) Learning Together and Alone: Cooperative, Competitive and Individualistic Learning (second edition). New Jersey: Prentice-Hall International Editions.

Global Education Guide. (2009). No authors listed.

http://ngomedia.pl/extranet/glen/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/GLEN-GE-Guide-2009.pdf

Kagan S., Kagan M. (2009) Kagan Cooperative Learning. San Clemente: Kagan Publishing.

Marjanovič Umek, L., Zupančič, M. (2004). Razvojna psihologija. Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni inštitut Filozofske fakultete.

Wambach, M. Wambach, B. (1999). Drugačna šola: Konvergentna pedagogika v osnovni šoli. Ljubljana: DZS.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Kindergarten Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

|