The Use of Team Teaching and its Effect on EFL Students' Proficiency in English

Robin Usher, Hungary

Dr Robin Leslie Usher Ph.D wrote a doctoral thesis `Jungian Archetypes in the work of [science fiction writer] Robert A. Heinlein`, 1992. Teacher of English language and literature since 1994. Has taught in Hungary, Poland, Russia, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Oman and Libya. Science fiction writer, 'All For Naught Orphan Ufonaut' in Shelter of Daylight, Sam's Dot Publishing (2010). Published in the British SF academic journal Foundation, `Male And Female He Created Them Both: Beyond The Archetypes` (112), and the Hungarian Institute for Educational Research`s Education, `Learning To Study`.

E-mail: robika2001@yahoo.co.uk

Menu

Background

Introduction

Student perceptions

Case study

Materials choice and course delivery

Assessment

Results and discussion

Conclusions and recommendations

References

Having taken a Bell-Obeikan International Placement Test, six EFL students classes (each comprising 20 EFL students) from the King Saud University`s Preparatory Year Diploma program, Riyadh, were first year level two (three male, three female). Two (one male, one female) taught by a team of local teachers ( non-native), two by native speakers; and two by a `mixed` pairing of native and non-native. In accordance with Saudi tradition, female classes were taught by females, and male classes were taught by males. Statistically, there was no significant interaction effect between the method of teaching and the students' gender in terms of the students' achieving in the English language proficiency test. Participants' scores were at α <0.05 (F= 3.32, P= 0.0399) in favor of the mixed method.

In the last decade, English language classrooms responding to the impact of English as a global language (Nunan, 2003), require team teaching, that is, foreign and local English teachers working together. Bringing foreign teachers from English-speaking countries to co-teach with local English teachers at the university first year level in Saudi Arabia is educational policy. In the last three years, the process has become a strategy for authentic language input. Native speakers facilitate cross-cultural communication, enhance students’ English ability, and promote local English teachers’ professional development (Nunan, 2003).

Team teaching, as a form of teacher collaboration, is in education at all levels. Co-teaching (Cook & Friend, 1996; Walther-Thomas et al., 1996; Roth & Tobin, 2001), cooperative teaching (Bauwen & Hourcade, 1995) and team teaching (Welch & Sheridan, 1995; Sandholtz, 2000) are synonyms. The main components are two educators, instruction, learners, and common settings.

Operational definitions result in varying amounts of collaboration and professional development, but team teaching itself is definable as allocation of teaching responsibilities; planning as a team, but with individual instruction; cooperative planning, instruction and evaluation of learning experiences (Sandholtz, 2000).

Team teaching improves the quality of teaching and learning in schools (Knezevic & Scholl, 1996; Smylie, 1995; Talbert & McLaughlin, 1993). Teaming, compared to teachers’ open discussion in regular meetings, is a collaborative practice requiring closer involvement with teammates’ work; such as peer coaching and interdisciplinary teaming. Teachers help each other and improve teaching practice by observing each other in the classroom, designing curricula, and/or teaching together. This makes intellectual, social, and emotional demands supportive of their motivation (Little, 2003).

Saudi Arabia has a short history (2007-) in team teaching. Since 2007, the Ministry of Higher Education`s preparatory year programs focused on English language. A minimum of eighty percent of teachers must be native speakers, and all work in pairs.

According to Bondy and Ross (1998) and George and Davis-Wiley (2000) team teaching`s essential elements are clearly defined and respectful relationships; agreement on methods of instruction, discipline, supervision of classroom aides and curriculum; planning, teaching, and assessing students together (Abdallah, 2009).

Yanamandram and Noble (2006) examined students experiences and perceptions about two models of team teaching in Australia. Data collected from 440 undergraduate students found the majority liked the concept of learning through interest in - and exposure to - teamed ‘experts’, but learning was hindered if the team failed to link adequately.

Collaboration contributes to students' learning progress (Durkin and Shergill, 2000). According to second and foreign language researchers (Tsai, 2007; Calderón, 1995, 1999; Tajino & Tajino, 2000; Tajino & Walker, 1998) teachers exchange ideas and cultural values, interact with and learn from one another. They observe how their colleagues teach, reflect upon and examine their own teaching practices, and improve.

In second language education in countries like the United States and Britain, team teaching is implemented at school level to provide authentic language input and culture, incorporate language and content instruction (Crandall, 1998; O'Loughlin, 2003), and integrate language minority and ESL students into mainstream classrooms (Becker, 2001; Coltrane, 2002; Creese, 2005; de Jong, 1996). A team of different linguistic, cultural, and educational background, better responds to students’ needs. This provides more opportunities to use the target language, learn more about diverse intercultural values, and foster positive attitudes towards communicating with native speakers (Carless, 2004, 2006; Luk, 2001; Meerman, 2003; Tajino & Tajino, 2000; Tajino & Walker, 1998).

In 2007, universities in Saudi Arabia started employing native English speakers to teach 20 hours per week to first year university students in cooperation with non-natives to upgrade English education. Team teaching`s primary concern is the sharing of experiences, and co-generative dialoguing. They take collective responsibility to improve and enhance students` learning.

The term `team teachers`, in this study, refers to shared teaching responsibilities; in planning lessons, in-class instruction, and follow-up work. According to policy, native speakers have English as their first language, and are from the United States, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, England, and Canada. Non-natives are Saudi or from Arab countries.

In language education team teaching is implemented to collaborate between ESL and mainstream teachers and integrate ESL students into the `mainstream` socially and academically (Becker, 2001; Creese, 2005). In contrast, traditional teaching isolates ESL learners from peers and mainstream curricula. Through team teaching students acquire English through meaningful content, and interactions with a native speaker (Tsai, 2007; Becker, 2001; Coltrane, 2002; O'Loughlin, 2003). In the ESL/mainstream team teaching model, teachers plan lessons together and decide on the roles they should play in class. Bailey, Curtis, and Nunan (2001) suggest `team teaching is [the] ... natural format for content-based instruction` (p. 183), which has increasingly been used (Thai 2007 and Kaspar, 2000). Bailey et al. (2001) identify five forms based on degrees of collaboration; direct content, team content, subsidiary content, supplementary content, and adjunct models (p. 182-183). Team content, subsidiary content, and supplementary content models typically involve the co-working of what might be termed `language and content` teachers in the same classroom. Team teaching`s `natural format` increases students’ motivation to learn a language through variations in language input (Crandall, 1998 and Grabe & Stoller, 1997).

English for academic purposes (EAP) and foreign language instruction have similar needs. In EAP team teaching enables students to obtain content-specific information, and receive support when encountering difficulties (Todd 2003). A native teacher and another, who shares the mother tongue and learning experiences of students, and can handle and explain cultural and analytic components of the target language, helps students acquire knowledge of the language and skills in using it (Davison, 2006).

Team teaching promotes bilingual students, but Creese (2005) showed ESL teachers were marginalized, having a supplementary role, addressing small groups as parts of classes in three schools she investigated. According to Creese (2005), subject and ESL teachers rarely developed `cooperative fully fledged teaching partnerships` (p. 202). Previous literature (Shibley, 2006) shows students benefit from knowledge in a team. It works well for the student, the practice teacher, the team, and service users (Davison, 2006).

There are four types of team teaching. Traditional in which both teachers share the instruction of content and skills; supportive in which one teacher focuses on content while the other teacher conducts follow-up activities or works on skill building; parallel instruction where students are divided into groups and each teacher provides instruction in the same content/skills to his or her group, and differentiated instruction, where students are divided into groups on the basis of learning needs, with each teacher providing instruction based on his or her group's needs. This requires dividing a class by ability to provide enrichment activities to the high ability group and extra support to the lower functioning group (Tonks, 2005). All previous studies compared team and individual teaching. The purpose here is to study the effect of the different forms (Creese, 2005 and Durkin & Shergill, 2000).

English is considered important because it`s the universal communicator, especially as the language of scientific research, technology, and business. English language ability offers students career opportunities. In spite of this, high school graduate students are often very weak in English language, because of teachers and teaching methods in secondary schools. Team teaching could provide a solution.

Because of the importance of English language, preparatory year programs, which main concern is teaching English, are established in Saudi Arabian Universities. These aim at the service of society, and ultimately the achievement of national goals and interests (Cf. the program for English Language Skills Program at the King Saud University, 2009-). Students are subjected to intensive language training for two semesters with an average twenty hours a week (i.e. six hundred hours in two semesters). The program aims to develop the students' competence in English and provide them with language skills they need in their academic and professional lives.

Although the program focuses on General English (communication) during the first semester, it moves in the second semester into English for Academic purposes; concentrating on reading and academic writing. During this period, students study English for Specific Purposes according to their academic disciplines. The students also start preparing for the global standard examinations (IELTS/TOFEL and PET), and finally sit them.

The program objectives are that students` advance in English language skills and linguistic competence; effectively communicate in English (written and spoken);acquire basic academic skills and ways of learning for academic success; prepare for international standard linguistic competence examinations (IELTS/TOFEL and PET) in order to (at least) meet the minimum requirements.

The English-language programs are provided by British and American companies like Bell International and Kaplan in Partnerships with University of Cambridge University Press and Pearson Longman, who develop curriculum and materials for Preparatory Year Programs in line with local culture and norms.

Before the start of the academic year, there is a placement test to determine the level of the students so they are placed in an appropriate level of study, according to their abilities and language skills. The placement tests are online based, computer based, or paper based tests. Based on results, students are divided into six levels (1-6).

The intensive English language program aims to develop students’ competence in the `four skills`: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Attention is given to grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation. An integrated skills approach is intended to improve students` accuracy and fluency (Usher, 2012).

The teaching staff is employed to be experienced and dynamic. Eighty percent use English as their first language. Academically and professionally qualified, no less than 40% hold a masters and/or PhD in addition to Cambridge English language teaching (CELTA and DELTA) certificates and diplomas.

Students` gender was one of the variables in the study because, in Saudi Arabia, male students have more freedom (to work, and socialize) than females. Consequently, they have more contact with native speakers, which assists their progress. All the students were Science majors.

The difficulties of team teaching include lack of time to plan and run individual lessons, and so poor communication between teamed teachers. Consequently, as part of their daily schedule and load, teams were given an hour a day to meet and discuss.

Each team had to prepare their lesson and lesson plans and to carry out the activities of the lesson together. The same material was used for the three groups. The study was carried out during the second semester of the academic year 2008/2009 and lasted 15 weeks. The textbook was Interchange 2, together with ESP material for Science major students, and PET test preparation.

Bell International Placement test is a standardized test of Cambridge University1 and its validity and reliability are established. Used several times, the researcher gave it to a number of EFL professors, managers, coordinators, and teachers in the English Language program to verify its suitability. They evaluated its clarity and relevance. All agreed the test valid and reliable.

By the end of week 15, and to assess the students' proficiency in English, all participants sat the Cambridge PET. The speaking part of the test continued over three days while the other parts (listening, reading and writing) were completed in one day. After correcting papers, according to the Cambridge marking system, students' marks were given out of 100% in accordance with the Saudi system. Then the results were sent to the students' college.

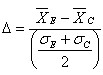

Students' results in the PET test were analyzed, using the SAS software. Means, standard deviations, the ANOVA test, and the effect size equation: were used to find out whether there were significant differences among students' results due to the teaching method and/or students' gender. were used to find out whether there were significant differences among students' results due to the teaching method and/or students' gender.

Table 1: Students’ Scores in the Placement Test

| Source |

N |

Mean |

Standard deviation |

| Method |

Two local teachers |

40 |

33.40 |

2.45 |

| Two native speakers |

40 |

33.025 |

2.25 |

| Native and non native |

40 |

33.075 |

2.12 |

| Gender |

Males |

60 |

33.28 |

2.26 |

| Females |

60 |

33.05 |

2.34 |

| Method |

Gender |

|

| Non Native |

Male |

20 |

33.95 |

2.28 |

| Non Native |

Female |

20 |

32.85 |

2.54 |

| Native |

Male |

20 |

33.25 |

2.27 |

| Native |

Female |

20 |

32.80 |

2.26 |

| Mixed |

Male |

20 |

32.65 |

2.13 |

| Mixed |

Female |

20 |

33.50 |

2.26 |

Table 1 shows the averages of the three groups were almost the same, and not gender determined. That males and females have different learning styles, and so require different teaching approaches, was outside the study`s purview. Table 2 shows differences among the mean scores of the students of the three groups after analysis. The non-native team`s mean score is 60.43 with a standard deviation of 7.37; the native team teaching`s mean score is 61.60 with a standard deviation of 7.22; and the mean score of the mixed team is 64.98 with a standard deviation of 9.62.

Table 2: Students’ Scores after the analysis

| Source |

N |

Mean |

Standard deviation |

| Method |

Two local teachers |

40 |

60.43 |

7.37 |

| Two native speakers |

40 |

61.60 |

7.22 |

| Native and non native |

40 |

64.98 |

9.62 |

| Gender |

Males |

60 |

61.83 |

9.25 |

| Females |

60 |

62.83 |

7.29 |

| Method |

Gender |

|

| Non Native |

Male |

20 |

60.70 |

8.86 |

| Non Native |

Female |

20 |

61.15 |

5.72 |

| Native |

Male |

20 |

61.25 |

8.03 |

| Native |

Female |

20 |

61.95 |

6.50 |

| Mixed |

Male |

20 |

63.55 |

10.85 |

| Mixed |

Female |

20 |

66.40 |

8.25 |

There was no statistically significant correspondence between the method of teaching and the students' gender, and no significant difference between the mean scores of male and female students. The mean for males was 61.83 and females 62.83. However, post analysis results show a statistically significant difference among participants' scores due to teaching method at α <0.05 (F= 3.32, P= 0.0399) in favour of mixed, that is, one native and one non-native, team teachers. There`s no significant difference between the team teaching method of native and non-native teachers.

In spite of the difficulties, such as preparation and training, finding time for team discussion, and the need for many-sided support from teachers, school administrators and parents, team teaching is a proven method.

Government sponsors, Saudi Exchange and Teaching Program (SET) attracts the necessary Assistant English Instructors (AEI), and the use of mixed team teaching allows a wider variety of instructional models than in a single teacher classroom (Tonks, 2005). Native speakers increase learner motivation, by encouraging socializing, promoting cross-cultural understanding, enabling more effective presentation of language content (especially dialogues), increasing learner participation, leading to the production of effective educational materials (Benoit and Haugh, 2001), and providing on-the job training for Saudi instructors of English. Teachers who share the students` culture understand their background, which is further enabling.

Teachers were asked, `Is it better to teach a class with two native speaking teachers, or one native and one non-native?` Answers varied. Mixed teachers complement each other. Non-native speakers are excellent in teaching grammar. In some cases perfect. Native speakers have a wider vocabulary, authentic accent and knowledge of idiom. Native speakers can be of assistance if need arises. Many students are frustrated by non-native accents. Pronunciation is the key to English, something non-natives struggle at. Non-natives have more understanding of students` difficulties because of their own approach to learnt English. Students also gain experience of differing accents. Teaching with a second native speaker is preferred due to cultural similarities, better understanding of one another; similar background, and no contradictions in grammar and pronunciation. In mixed teaching there`s a more integrated understanding between students and teachers.

Co-operation increases contact and reduces psychological stress because it facilitates cross-cultural communication (Abdallah, 2009). According to Honigsfeld and Dove (2008) co-teaching is `inclusive` and so more accommodative of the needs of diverse English language learners and, of no less importance, exposes native speakers to students from our culture.

In conclusion, a mixed team better responds to students’ needs. The model provides students with more opportunities to use the target language, learn more about intercultural values, and foster positive attitudes towards communicating with native speakers. Differences in cultural background, and learnt teaching strategy, expose team teachers to being challenged by students based on comparisons in class. Mixed teaming promotes collaboration and mutual assistance to improve their concept of teaching strategy and class management.

Cooperation serves communication. Mixed teaming provides a communicative model in the target language. Through parallel or differentiated instruction, learners receive more personal instruction time. Because learners are taught by more than one teacher, there is an increased chance of an instructional style conducive to an individual`s learning capacity (Goetz, 2000).

The study recommends investigating the effect of team teaching on students’ proficiency in each of the four language skills (listening, reading, speaking, and writing), e.g., by means of the Cambridge PET test, and also an investigation of the effect of mixed team teaching in school education.

Abdallah, Jameelah (2009) `Benefits of Co-Teaching for ESL Classrooms` Academic Leadership Online Journal, 7(1). Retrieved on 15/8/2009 from

www.academicleadership.org/emprical_research/532.shtml .

Bailey, Kathleen. M., Curtis, Andy, & Nunan, David (2001) Pursuing Professional Development: The Self As Source, Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Bauwens, Jeanne; Hourcade, Jack J (1995) `Cooperative Teaching: Rebuilding the School House for all Students` (Austin, TX, PROED).

Benoit, Rebecca & Haugh, Bridget (2001)`Team Teaching Tips for Foreign Language Teachers` The Internet TESL Journal 7(10). Retrieved on 9 August, 2005

http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Benoit-TeamTeaching.html .

Becker, Helene (2001) Teaching ESL K-12: Views from the Classroom, Boston: MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Bondy, Elizabeth; Ross, Dorene (1998) Teaching teams: Creating the context for faculty action research Innovative Higher Education, 22(3), pp. 231 – 249.

Calderon, Margarita (1995) Dual Language Program and Team-Teachers' Professional Development, Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA.

Calderón, Margarita (1999) `Teachers Learning Communities for Cooperation in Diverse Settings`, Theory into Practice, 38, pp. 94-99.

Carless, David R (2004) JET and EPIK: Comparative Perspectives, Paper presented at the KOTESOL, Busan, Korea.

Carless, D. (2006) `Collaborative EFL Teaching in Primary Schools`, ELT Journal, 60, pp. 328-335.

Bronwyn, Coltrane (2002) `Team teaching: Meeting the Needs of English Language Learners Through Collaboration`, ERIC/CLL News Bulletin, Spring 2002. Retrieved April 5, 2005, from www.cal.org/resources/News/2002spring/team.html .

Cook, Lynne; Friend, Marilyn (1996) `Coteaching: Guidelines for Creating Effective Practices` in: E. L. Meyen, G. A. Vergason & R. J. Whelan (Eds.) Strategies for Teaching Exceptional Children in Inclusive Settings (Denver, OH, Love), pp. 155 -182.

Crandall, Jo Ann (1998) `Collaborate and Cooperate: Teacher Education for Integrating Language and Content`, English Teaching Forum, 36, pp. 2-9.

Angela, Creese (2005) Teacher Collaboration and Talk in Multilingual Classrooms, Frankfurt, UK: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Davison, Chris (2006) `Collaboration Between ESL and Content Teachers: How Do We Know When We Are Doing It Right?` The International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 9, pp. 454-475.

De Jong, Ester Johanna (1996) Integrating: What Does it Mean for Language Minority Students? Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Association for Bilingual Education, Orlando, Florida.

Durkin, Christopher, and Sheirgill, Makhan (2000) `A Team Approach To Practice Teaching`, Social Work Education, 19( 2), pp. 165-174.

George, Marshall A.; Davis-Wiley, Patricia (2000) `Team Teaching A Graduate Course: Case Study: A Clinical Research Course`, College Teaching, 48(2), pp. 75-80.

Goetz, Karin and E. Gallery (2000) `Perspectives on Team Teaching`, EGallery. University of Calgary. Retrieved on 9 August, 2009, www.ucalgary.ca/~egallery/goetz.html .

Grabe, William., & Stoller, Fredricka L (1997) `Content-Based Instruction: Research Foundations` in M. A. Snow & D. M. Brinton (Eds.) The Content-Based Classroom: Perspective on Integrating Language and Content , White Plains, NY: Longman, pp. 5-21.

Honigsfeld, Andrea, & Dove, Maria (2008) `Co-teaching in the ESL Classroom`, The Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin, 2, pp. 8-14.

Tsai, Jui-min, M. (2007) Team Teaching and Teachers’ Professional Learning: Case Studies of Collaboration Between Foreign and Taiwanese English Teachers in Taiwanese Elementary Schools. Ph.D Dissertation, Ohio State University. Retrieved on 20/11/2009 from http://etd.ohiolink.edu/etd/send-pdf.cgi/Tsai%20Juimin.pdf?acc_num=osu1186669636 .

Kasper, Loretta F. (2000) Content-based College ESL Instruction, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Knezevic, Anne., & Scholl, Mary (1996) `Learning To Teach Together: Teaching to Learn Together` in D. Freeman & J. C. Richards (Eds.) Teacher Learning in Language Teaching, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 79-96. Retrieved on 15/11/2009 from http://etd.ohiolink.edu/etd/send-pdf.cgi/Tsai%20Juimin.pdf?acc_num=osu1186669636 .

Little, Judit W. (2003) `Inside Teacher Community: Representations of Classroom Practice`, Teachers College Record, 105, pp. 913-145.

Luk, Ching M. (2001) `Exploring the Sociocultural Implications of the Native English-Speaker Teacher Scheme in Hong Kong Through the Eyes of the Students`, Asia Pacific Journal of Language in Education, 4, pp. 19-49.

Meerman, Arthur D. (2003) `The Impact of Foreign Instructors on Lesson Content and Student Learning in Japanese Junior and Senior High Schools, Asia Pacific Education Review, 4, pp. 97-107.

Nunan, David (2003) `The Impact of English as a Global Language on Educational Policies and Practices in the Asia-Pacific Region`, TESOL Quarterly, 37, pp. 589-612.

O'Loughlin, Judith B. (2003) `Collaborative Instruction in Elementary School: Push-In vs Pull-Out`, The ELL Outlook, 2. Retrieved April 5, 2005, from

www.coursecrafters.com/ELL-Outlook/2003/Outlook_0403.pdf .

Roth, Wolff-Michael. & Tobin, Kenneth (2001) `Learning to Teach Science as Practice`, Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(6), pp. 741 – 762.

Sandholtz, Judith H. (2000) `Interdisciplinary Team Teaching as a Form of Professional Development`. Teacher Education Quarterly, 27(3), pp. 39 – 50.

Smylie, Mark A. (1995) `Teacher Learning in the Workplace: Implication for School Reform` in T. R. Guskey & M. Huberman (Eds.), Professional Development in Education: New Paradigms and Practices, New York: Teachers College Press, pp. 92-113.

Tajino, Akira, & Tajino, Yasuko (2000) Native and Non-Native: What Can They Offer?` Lessons from Team Teaching in Japan`, ELT Journal, 54, pp. 3-11.

Tajino, Akira; Walker, Larry (1998) `Perspectives on Team Teaching by Students and Teachers: Exploring Foundations for Team Learning`, Language, Culture, and Curriculum, 11, pp. 113-131.

Talbert, Joan E.; McLaughlin, Milbrey Wallin (1993) `Understanding Teaching in Context` in D. K. Cohen, M. W. McLaughlin & J. E. Talbert (Eds.) Teaching for Understanding: Challenges for Policy and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

King Saud University English Skills Program Preparatory Year (2009). Retrieved from www.py.ksu.edu.sa .

Todd, Richard Watson (2003) `EAP or TEAP?` Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 2, pp. 147-156.

Tonks, Basil (2005) `ESL Team Teaching in the Japanese Context`, The International TEYL Journal. Retrieved on 9 August, 2009 www.teyl.org/article12.html .

Shibley, Ivan, A. (2006) `Interdisciplinary Team Teaching: Negotiating Pedagogica; Differences`, College Teaching, 54(3), pp. 122-126.

Usher, Robin, L. (2012) `Accuracy versus Fluency`, Humanizing Language Teaching, 14, 2. old.hltmag.co.uk .

Walther-Thomas, Chriss, Bryant, Mimi & Land, Sue (1996) `Planning for Effective Co-Teaching: the Key to Successful Inclusion, Remedial and Special Education, 17, pp. 255-265.

Welch, Marshall & Sheridan, Susan M. (1995) Educational Partnerships: Serving Students at Risk, Fort Worth, TX, Harcourt Brace.

Welch, Marshall; Brownell, Kerrilee & Sheridan, Susan M (1999) ‘What’s the Score and Game Plan on Teaming in School’: A Review of the Literature on Team Teaching and School Based Problem Solving Teams, Remedial and Special Education, 20, pp. 36-49.

Yanamandram, Venkata. and Noble, Gary. (2006) `Student Experiences and Perceptions of Team-Teaching in a Large Undergraduate Class,` Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, Vol. 3, #1, Article 6. Retrieved on 15/11/2009 from

http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?articles=1043&context=jutlp

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|