No Regrets: Help with Teaching “The Counterfactual”

James Scotland, Qatar

James Scotland currently teaches English in the Post Foundation Programme at Qatar University, having previously taught in England, Australia, Canada, Turkey and South Korea. His professional interests include classroom materials development and language teacher education.

E-mail: jamesscotland@gmail.com, scotland@qu.edu.qa

Menu

Introduction

What is ‘The Counterfactual’?

How is “The Counterfactual” expressed?

Why can “The Counterfactual” be problematic?

Teaching solutions

References

This article explains what counterfactual thinking is, highlights how it is expressed, examines how the counterfactual is problematic to learners then suggests several practical teaching solutions.

Everyone wonders about what might have been, had a past choice been different. Perhaps with a little more effort you might have been a doctor, maybe you should have studied harder in school or traveled more. Everyone has regretted choices made and actions taken.

Thinking about what might have been, about alternatives to our own past, is central to human thinking and emotion. This psychological process is known as counterfactual thinking. Counterfactual thoughts are often evaluative, specifying alternatives that are in some way better or worse than actuality. Individuals rerun past events, changing aspects of their actions, seeing if, and how, this would have made a difference. Thus, counterfactuals have a strong relationship with regret.

Regret allows people to focus on prevention, plan for the future and learn from mistakes. Regret is important; consequently, all learners of English need to understand how to use the language of regret.

In English, the third-conditional and past perfect wish-clauses express counterfactuality via a combination of clauses, each containing differing grammatical structures. Additionally, the polarity of each clause can be positive or negative, for example:

- If I had studied, I would have passed.

- If I had looked, It would not have happened.

- If I had not missed, we would have won.

- If I had not kissed her, she would not have slapped me.

|

The avoidance of the third-conditional and wish-clauses is commonplace in higher-level learners, as grammatically simpler alternatives are often preferred.

|

- I wish that I had danced.

- I wish that I had not danced.

- I do not wish that I had danced.

- Do you wish that you had danced?

Furthermore, the semantic/lexical field of regret contains a variety of lexical chunks.

- I should have driven.

- I regret not driving.

- I’m sorry I drove.

- Just Imagine if I drove.

The third-conditional and past perfect wish-clauses express regret by using the past perfect to refer to a counterfactual world. This can be problematic both conceptually and grammatically for higher-level learners.

A counterfactual statement creates a complex hypothetical world that counters reality. Past perfect is used to refer to hypothetical events that did not happen in the past. Misunderstanding this connection is problematic. In order for students to understand the language of regret, it is imperative that they understand how grammatical structures can express an alternate reality.

Conditionals need something to be fulfilled in order for something else to happen. Aitken (2001, p. 95) states:

“Conditionals are patterns expressing the relationship between two actions, where one action is the reason, or occasion, for the other.”

Students might not understand this connectivity.

Counterfactuals are a powerful linguistic tool. Quill et al (2001) illustrates how doctors can use wish clauses to express patient empathy while simultaneously evading admission of error i.e. the doctor responsible for a failed operation might say to a patient, “I wish that the operation had worked.”

Furthermore regret can be subjective; therefore, interpretation of utterances and events is dependent on an interlocutor’s belief system. Subtlety inflected implied meaning makes using counterfactuals confusing i.e. a married woman might say to her lover, “I wish I’d married you,” but this does not necessarily mean that she wants to divorce her husband.

Often students are not aware how language is manipulated outside the classroom, and in my experience, many ESL/EFL grammar textbooks or standard reference grammars do not raise students’ awareness of pragmatic use.

A counterfactual statement creates a complex hypothetical world that counters reality. Conditional and wish clause structures use the past perfect is used to refer to impossible events that did not happen in the past. The following activity aids students in understanding how expressions of regret relate to reality by making the language’s semantic meaning visually explicit.

Aim - To raise awareness of the semantic meaning of target-language.

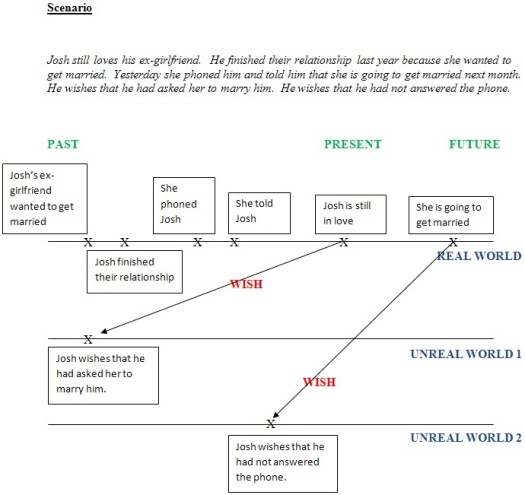

Activity - Students are given a scenario containing the target language. In pairs the students transfer the events in the scenario onto a multi-layered timeline. Figure-1 illustrates.

In Figure-1 the wish-clauses contain the past perfect; however, they are linked to the present. Students need to understand this relationship. Concept checking questions are invaluable. Concept questions for counterfactuality should clarify form, meaning, use, and make inherent time and tense relationships explicit. Regarding the above scenario, the following concept check questions can be used.

- Did Josh’s wishes come true?

- Will Josh’s wishes come true? Why?

- Why are the things that Josh wished for on the unreal world timelines?

- If Josh had asked her to marry him would she have said yes?

- Would she have met another man?

- Would she have called Josh?

- Why are there two unreal world timelines?

A study using counterfactual conditionals, (Song and Suh, 2008, p. 306) found that output opportunities promoted significantly greater noticing of the target language. Students need opportunities to produce the language. The following production activity focuses on raising students’ awareness of the connectivity of counterfactuals.

Aim - To raise awareness of the connectivity of counterfactuals

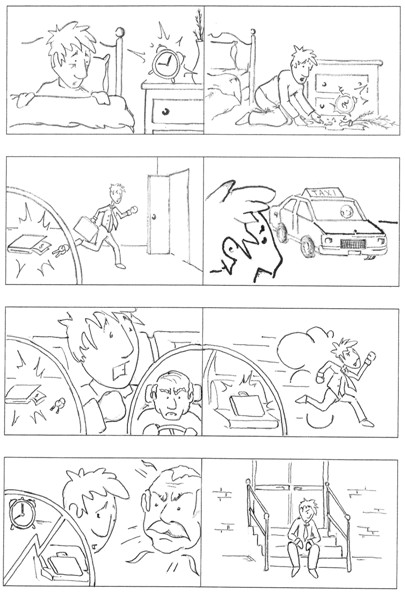

Activity - Students are given pictures which depict a series of dependent situations. Figure-2, illustrates.

Word Bank

wake up late break the alarm clock forget wallet and keys

take a taxi pay (not) the taxi fare leave briefcase in the taxi late for work

Figure 2- Series of Pictures

Illustrations by Adam Merrick (abmerrick@gmail.com)

In pairs, students write a narrative containing the target language onto an overhead transparency (OHT).

Sample narrative - John woke up late. He left for work in a hurry. He forgot to take his keys and wallet. If he hadn’t woken up late, he would not have been in a hurry.

During feedback students’ OHT's will be shown to the class. The target language should be identified and checked for form and meaning.

When learners do not have to attend to the cognitive burden of content, output practice of a newly learnt grammatical structure is more effective. The illustrative text and word bank above allow students to primarily focus on the connectivity inherent within counterfactuals rather than formulating new scenario.

In my experience, grammar books place a high focus on the form and meaning of counterfactuals often omitting use. Understanding another’s perspective, motives and emotions can be difficult. Consequently, successful teaching of counterfactuals requires a focus on pragmatics. Students need scenarios which require carefully considered language choices; selecting and comparing expressions of regret in context will aid implicational understanding, thus moving from declarative to procedural knowledge.

Aim - To raise awareness of the pragmatic implications of counterfactuals

Activity - Students are given situations in which regret needs to be expressed. Students must choose the most appropriate language from several options and justify their choice e.g.:

A doctor has to inform a heart transplant patient that their operation has failed, consequently the person will die. What should the doctor say?

- You’re gonna die.

- I am sorry but the operation failed.

- I wish that the operation had worked.

- If the operation had worked, then you would have been saved.

In my experience, the above activity creates a need for the target language, thus reducing learner avoidance. Furthermore, students can produce their own counterfactual sentences for the scenarios.

Regret is implicit and subjective. Students need to be exposed to texts containing non-overt conditionals. Pragmatically examining texts holistically determining exactly what the speaker is implying.

Aim - To raise awareness of how regret can be implied.

Activity - Students are given an authentic text that uses wish-clauses and incomplete third-conditionals to imply regret. Students identify statements of regret, implied meaning is then discussed. Suitable texts include newspaper articles, biographies and novels.

Interpreting a scenario in which a past event is perceived in different ways illustrates the subjective and personal aspects of regret.

Teaching counterfactuality can be difficult; hopefully, I have added to your understanding of the issues involved and given you some practical classroom solutions. Thus, you have no regrets about the time you just gave.

Aitken R. 2001. “Teaching Tenses”. Longman. Essex. England. ISBN 0175559201

Quill T E. Arnold R M. Platt F. 2001. “I Wish Things Were Different: Expressing Wishes in Response to Loss, Futility, and Unrealistic Hopes”. Annals of Internal Medicine. Vol 135. No 7. October 2001

Song M J. and Suh B R. 2008. “The Effects of Output Task Types on Noticing and Learning of the English Past Counterfactual Conditional”. System. 36 (2008) p295-312

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|