Developing Pragmatic Skills and Conversational Strategies in Speaking Competence

Talat Bulut, Selcuk Bilgin, Huseyin Uysal, Turkey

Talat Bulut completed his major in English language teaching and double major in German language teaching at Istanbul University in 2009, and taught English at Hacettepe University between 2010 and 2012. He got his M.A degree in English Linguistics at Hacettepe University, and is currently a PhD student in Cognitive Neuroscience at National Central University. His areas of interests are relative clauses in Turkish and neurolinguistics.

Email: buluttalat@gmail.com

Selcuk Bilgin got his B.A degree in English Language Teaching from Marmara University in 2008, and has been teaching English at Hasan Kalyoncu University since 2011. He is studying at the M.A program in Professional Development for Language Education at Norwich Institute for Language Education in partnership with University of Chichester. His research interests are motivation factor in reading, teaching English to adult learners and educational technology.

Email: selcukblgn@hotmail.com

Huseyin Uysal received his B.A degree in English Language Teaching from Mehmet Akif Ersoy University in 2011, and has been working as an English language lecturer at Hasan Kalyoncu University and studying at the M.A program in Linguistics at Ankara University since then. His research interests include conceptual development and figurative language comprehension in Turkish children.

E-mail: huysal9@gmail.com

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Review of literature

The scope of the issue

Suggestions provided in the literature

Possible implementations in the classroom

Conversational strategies: role-play activity

Awareness-raising activity: Sorting Closings and Cocktail Party

Awareness-raising activity- repairs and practice activity: Say that Again?

Conclusion

References

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

This paper examines to what extent pragmatic skills or conversational strategies can increase the speaking competence of language learners. It also discusses what is needed to able to communicate in L2 with other people, and whether speech means a chain of words or sentences that are grammatically connected. In this study, we aim to find answers for these questions, to incorporate pragmatic competence and conversational strategies into practice, and to offer some suggestions beyond linguistic competence on some course books activities. The first activity for which we offer some possible implementations is a Role Play which consists of Opening statements, Monitoring Expressions, Negotiating meaning, Politeness and Closing expressions. Another activity which can be considered as awareness-raising is Sorting Closings and Cocktail Party which includes pragmatic conversations. Say that again?, as the last activity, is a Repairs and Practice activity aiming to restate, clarify and reformulate what the speaker says.

Among the language skills, speaking seems to be the most intimidating to the majority of students in our country. This may stem from the simultaneity and streaming nature of the speaking process-a quality shared by the listening skill-unlike the other two skills, writing and reading. Being an ongoing activity, speaking necessitates attention, alertness, clarity among others, and these may be especially difficult to maintain in cross cultural situations as the lack of shared background means more difficulty in bridging the gaps between the interlocutors. However, one of the main objectives of learning a foreign language is being able to communicate with foreigners, probably not with fellow country people. To do that requires not only linguistic competence such as grammar, comprehension and other kinds of abilities in the target language, but also conversational strategies which will help develop a healthy conversation and maintain it properly. Speech is not just a string of words or sentences that are grammatically attached to each other. This can be at most a piece of writing, a lacking one, though. For conversation to take place one needs to have pragmatic knowledge about the conversation situation, the ability to carry on a conversation. Among pragmatic knowledge or competence we can list such sub-abilities as the ability to open and close a conversation, to monitor, take turns and negotiate meaning in an efficient way. These are also essential components of a communication event, not less important than the use of correct grammar or correct choice of vocabulary, and probably more important than those. These abilities more often than not compensate for linguistic deficits and thus can render a foreign language speaker a more competent and efficient speaker in spite of lack of linguistic competence while another speaker may suffer greatly because of absence of pragmatic competence despite advanced linguistic abilities. The pragmatic sub-skills mentioned above-opening, closing, monitoring, turn taking, negotiating meaning, among others- are highly culture/language-specific; that is, conversations function in every language by making use of those conversational dynamics; however, they tend to change shapes, meanings, denotations and connotations from language to language and from culture to culture.

The objective of this paper is to incorporate pragmatic competence and conversational strategies into practices of teaching English. As is pointed out above, there is more to speaking or conversing than just strings of grammatical utterances or words. Successful communication necessitates pragmatic competence, which changes form and realization from language to language. The implications of such an assertion are that when we teach a foreign language, there is a good chance that learners are faced with quite different conversational strategies in the target language from their mother tongue. Therefore, they may perform transfers from their language and these may turn out to be inappropriate in the target language context. Besides, they may simply have much difficulty to learn them properly because of L1 interference. In this paper, a hands-on and explicit approach to teaching conversational strategies is proposed. In this way, it is argued that problems in speaking in spite of fair language capacity can be overcome to a certain degree.

Canale and Swain (1980) define strategic competence as “verbal and non-verbal communication strategies that may be called into action to compensate for breakdowns in communication due to performance variables or to insufficient competence”(1980). Although some favor teaching communication strategies in a direct way (Oxford, Lavine and Crookall, 1989), some others are skeptical about it (Ridgway, 2000). Supporters of teaching conversational strategies argue that they are required for development of strategic competence (Dörnyei and Thurrell, 1991, 1994; Færch and Kasper 1986). According to Dörnyei and Thurrel (1994), it has been neglected that carrying out conversation also involves knowing how to use language to interact. It is not solely important that what learners produce be grammatical or accurate (indeed, this is not the case even when we speak in our L1), a crucial factor in conversation is how effectively one takes part in conversational exchanges. Indeed, conversation “involves far more than knowledge of the language system and the factors creating coherence in one-way discourse; it involves the gaining, holding and yielding of turns, the negotiation of meaning.” (Cook 1989: 117).

As is seen, there are certain aspects in conversation which is beyond accurateness or grammaticalness but which are vital for a healthy conversation. Though there are studies in the literature about the pragmatic and strategic aspects of conversation, there is the need to implement the necessary teaching practices into the foreign language classroom and to do that by taking the relevant L1 and its culture into account.

As regards communication strategy training, the advocators of direct handling of the issue in the classroom argue for certain practices. For instance, Færch and Kasper (1986) suggest three specific activity types to practice communication strategies. These are communication games with visual support, without visual support, and monologues. They also recommend increasing students’ meta-communicative awareness about the factors that determine appropriate strategy selection through certain analytic tasks, such as audio/video tape analysis of non-native speaker-native speaker discourse. Willems (1987) presents recommended CS instructional activities to practice paraphrase and approximation (e.g., crossword puzzles, describe the strange object). He argues that “our first task is to train them [learners] ‘not for perfection but for communication.’ Correctness-errors, which learners will make anyhow, may reasonably be compensated for in interaction by skillfulness [sic] in the use of CmS” (i.e., communication strategies) (p. 361). While Tarone and Yule (1989) advocate CS be taught in a focused and explicit way (p. 114), Dörnyei and Thurrell (1991, 1994) suggest the use of both traditional communicative language teaching activities as well as consciousness-raising tasks. Dörnyei, on the other hand, proposes six procedures which may help communication strategy development of learners:

- Raising learner awareness about the nature and communicative potential of CSs

- Encouraging students to be willing to take risks and use CSs

- Providing L2 models of the use of certain CSs

- Highlighting cross-cultural differences in CS use

- Teaching CSs directly

- Providing opportunities for practice in strategy use

Wong and Waring (2010) propose certain activities to develop pragmatic competence. In terms of turn taking, for instance, they suggest an awareness-raising activity which start with asking students to brainstorm about how we know someone is about to stop speaking. In the second stage of the activity, students listen to an authentic conversation. The teacher gets students to listen to someone’s turn in the conversation and s/he stops the recording after each word. Students’ task is to decide when the speaker is going to stop. The teacher elicits pragmatic knowledge by asking how they knew when the speaker was going to stop (prosodic/intonational, grammatical, etc. cues). Alternatively or additionally, students may indicate possible completion points (where the speaker can stop and the other can take the turn) in a transcribed conversation. As a final step, students are asked to compare the L2 turn taking conventions to those of their own tongue. Another activity to practice is turn taking skills suggested by Wong and Waring (2010) focuses on adjacency pairs. The teacher hands out different answers written on slips of paper to each student. Half of the class has the same answers as the other half. Students stand up. Teacher reads different questions and the student who answers the question most quickly sits down. Here students need to check for signals in teacher’s questions that point to a completion point, which develops being aware of turn taking cues in the spoken input.

The writers also provide an activity to practice how to close a conversation. Teacher asks students to go about the classroom as if they are at a cocktail party. They have something to drink and some snacks to munch on. They are supposed to make small talk with one another for 2-3 minutes until the teacher gives them a 1-minute-left warning (e.g. with a bell). During this 1-minute span, they are to bring the current conversation to a close. When the time is up, they move on to chat with another classmate. Teacher gives students cue cards before the party stars which guides them how to close the conversations such as arrangements, announced closings, etc. At the end, feedback is taken and possible questions are answered.

Sayer (2005) moves from the problem of discrepancy between L1 and L2 pragmatic differences and carries out an action research addressing such pragmatic procedures as monitoring, turn taking, negotiating meaning. He makes use of role plays to make students aware of ritualistic and pragmatic expressions and conventions in L2 conversations, which he claims does help learners’ development of conversational skills.

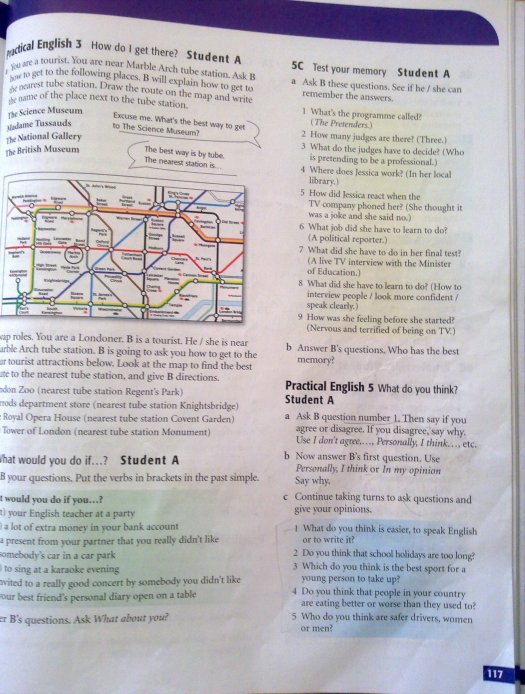

This activity is devised to modify and ‘pragmatize’ Practical English 3 task in NEF Intermediate, p 117 and 120). The original task can be seen in the Appendix I. the task asks students to work in pairs and engage in conversation with a Londoner and ask him/her for directions on a London tube map. The prompts provided for the activity are rather scarce; i.e. just one opening structure with a question about the place of inquiry together with a possible answer. This seems rather ineffective and may prove too weak to engage learners in a natural conversation which makes use of pragmatic aspects. In the modified version, the procedure below is followed:

First, the following opening, monitoring, taking the floor, negotiating meaning, politeness, and closing expressions are explicitly taught to the class.

Opening statements:

Pardon me, how can I go to ….

Excuse me, I am looking for ….

Monitoring expressions:

Hmm…

I know what you mean.

I know that place.

Well, I didn’t get that.

Sorry, can you repeat what you said?

Taking the floor:

A: … go ahead and you will see the tube station on your right, after that…

B: Sorry, is it the Gouch Street tube station or the Piccadily?

Negotiating meaning:

A: ….You know what I mean?

B: you say I should take the blue line, not red, right?

Politeness:

Excuse me, Sir/Madam…

Not: I want to go to …

Closing:

That was really helpful, thank you.

Many thanks.

I appreciate that.

These expressions are explicitly taught to the class. Before starting the direction-giving, a pair of students is invited to the front. Two slips of paper are given to each. On each slip, there is a role such as:

Role 1

“You are a tourist. You want to go to Oxford Street. Ask the stranger how to get there by using such expressions as: “Tell me how to go to…/I want to go to…” Be rude and direct. Do not thank. Stop him/her while s/he is talking by saying “Ok, Ok. I understood.” Show him/her that you don’t listen and don’t understand anything. Just leave the stranger when you have the information.”

Role 2

“You are a Londoner and a tourist stops you and asks for directions to Oxford Street. Give the information but try to be rude.”

After the role play, it is evaluated in terms of the above mentioned points as a class. Students point out the problematic parts and offer solutions and suggestions. Suggestions are written on the board.

Then the students are asked to carry out the task in an appropriate way by taking into account what was discussed in the previous part.

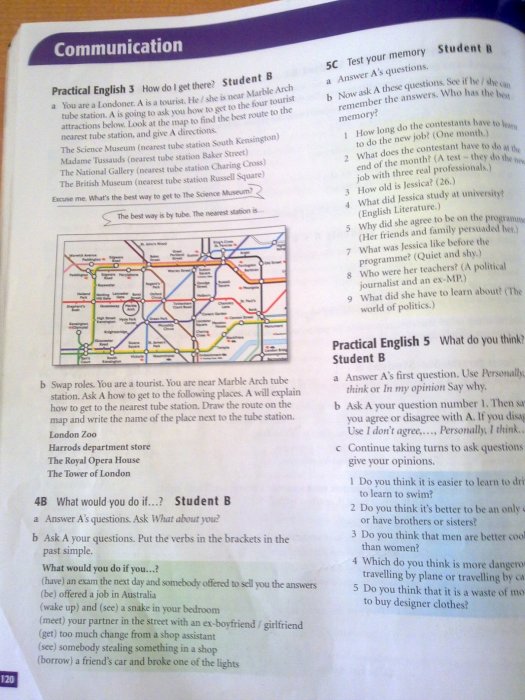

Another modification is made to the speaking activity on NEF Intermediate, p. 60. The original activity can be seen in the Appendix II. The second part of the vocabulary and speaking activity requires students to talk about their close friends with their classmates. The activity is in the interview format, with only questions given as a prompt. The original activity necessitates practically no interaction from students. Instead, this can be turned into a more natural conversation with pragmatic considerations. Steps in carrying out the modified version are as follows:

The task has two main sections: Awareness-raising Activity: Sorting Closings and Cocktail Party

Awareness-raising Activity: Sorting Closings

First, students are asked to brainstorm about how we can close conversations. Answers are evaluated.

Then, (books closed) teacher projects the following table on the screen where each student can clearly see:

Pre-closing Sequences Examples

| 1. Arrangement |

I’ll see you in the morning. |

| 2. Appreciation |

Thank you. |

| 3. Solicitude |

Take care. |

| 4. Back-reference |

So what are you doing for Thanksgiving? |

| 5. In-conversation object |

Mm hmm? |

| 6. Topic-initial elicitor |

Anything else to report? |

| 7. Announced closing |

OK, let me get back to work.

OK, I’ll let you go.

|

| 8. Moral or lesson |

Yeah well, things always work out for the best. |

Students are asked to explain the types of pre-closing by looking at the examples. Help is provided if students have problems understanding the concepts.

In the third stage, the following conversation parts are given to each pair of students as hand-outs:

(a) [Button, 1990, pp. 97–98—modified]

01 Emma: um sleep well tonight sweetie,

02 Lottie: Okay well I’ll see you in the morning.

03 Emma: Alright,

04 Lottie: Alright,

05 Emma: Bye bye dear.

06 Lottie: Bye bye.

(b) [Button, 1990, p. 121—modified]

01 John: I’ll see you over the weekend then.

02 Steve: Good thing.

03 John: Okay, and I’m glad I rang now and sorted

04 things out.

05 Steve: Yeah me too.

06 John: Okay then.

07 Steve: Okay,

08 John: B[ye.

08 Steve: [Bye.

(c) [Button, 1990, p. 105—modified]

01 Alfred: Well, we’ll see what happens.

02 Lila: Okay,

03 Alfred: Thank you very much Mrs. Asch,

04 Lila: Thanks for calling,

05 Alfred: Goodbye,

206 Conversation Analysis and Second Language Pedagogy

06 Lila: Bye bye.

(d) [Button, 1990, p. 104—modified]

01 Marge: Tell your girlfriend I said hello.

02 Sam: I will dear.

03 Marge: Okay.

04 Sam: Thank you,

05 Marge: Bye bye,

06 Sam: Bye bye.

Students are asked to categorize the closing expressions in the conversations according to the categories taught previously (which are still projected onto the screen for reference). Answers are checked when students have finished and comparisons to L1 conversation closings are made as a class.

The second part of the task: Cocktail Party

In the second part, students practice what they have learned about closings. Students are told that they are at a cocktail party. They have drinks (alcohol-free) and snacks. As is explained in the provided suggestions section, they are told to have a conversation with a classmate for 2-3 minutes but when they hear the bell ring (which the teacher does), they are required to close their conversations in one minute. When the bell rings, they change partners. The topic of conversation is close friends. Students are told to mention one of their close friends and ask about and give information about him/her using such questions as:

How long have you known him / her?

Where did you meet?

Why do you get on well?

What do you have in common?

Do you ever argue? What about?

How often do you see each other?

How do you keep in touch the rest of the time?

Have you ever lost touch? Why? When?

Do you think you'll stay friends?

The third implementation concerns repairs in conversations. A repair is carried out when the speaker wants to restate, clarify and reformulate what s/he wants to say (self-initiated) or when the addressee does not understand what the speaker says and asks for restatement (other-initiated). Here the latter is focused on.

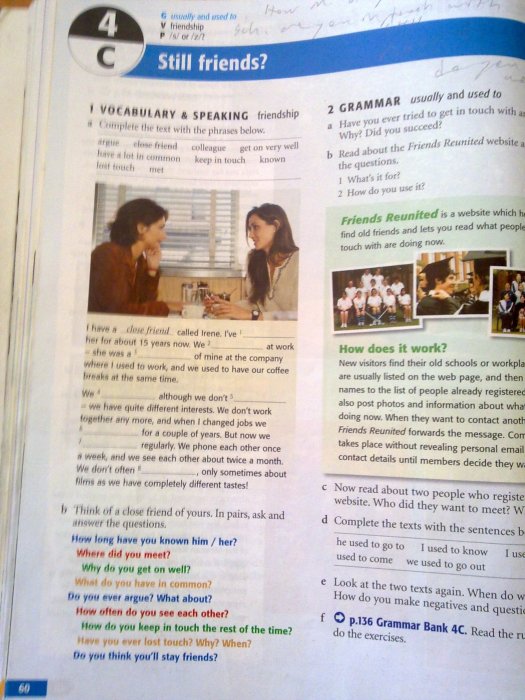

The activity to which modification is applied is in Interactions 2, p. 192 (Before you listen the first activity), which can be found in Appendix III. The context is describing ideal partner. Firstly students are asked to write some qualities of a possible romantic partner, which they share with their classmates. Again the task is composed of two main parts.

Part I: Awareness Raising Activity: Repairs

Firstly, answers are elicited for the following questions:

(a) When you do not hear or understand what someone has said, what do you usually say?

(b) Do you know of any ways of asking someone to repeat if you did not hear or understand it? If so, what are they?

Afterwards, the following is distributed to each pair as hand-outs:

[Schegloff, 1997b, p. 515—modified]

01 A: And okay do you think you could come?

02 Pretty much for sure?

03 B: What?

04 A: Do you think you could come pretty much for sure?

05 B: Sure.

[Schegloff, Sacks, and Jefferson, 1977, p. 368—modified]

01 B: By the way, I have to go to Lila’s.

02 A: Where?

03 B: Lila’s to get my books.

[Sacks, 1992a, p. 8]

01 A: Okay, uh I was saying my name is Smith and I’m

02 with the Emergency Psychiatric Center.

03 B: Your name is what?

04 A: Smith.

05 B: Smith?

06 A: Yes.

[Wong phone data]

01 B: Wa- I was wondering if you were gonna be home

02 tomorrow afternoon I could maybe come over after

03 summer school.

04 (0.4)

05 A: Um:: I’ll be at my mother’s tomorrow afternoon.

06 B: Oh::=

07 A: No I’m just sitting there waiting for an oil burner

08 man=you can come over then.

09 B: You’re sitting there waiting for an oil burner?

10 A: Yeah(h)(h) .h heh:: No:: you know you have to

11 (h)(h)huh-hih I

12 think I am=I’m not sure (0.2) um:: you know you

13 have to get the burner cleaned or something for the

14 summer?

[Schegloff et al., 1977, p. 369—modified]

01 B: How long are you going to be here?

02 A: Uh not too long uh just till uh Monday.

03 B: Oh you mean like a week from tomorrow.

04 A: Yeah.

Students are told to read through the conversations and decide which expressions get the speaker to repeat what s/he has said and then to match these expressions with the categories below:

(a) Huh? Pardon? Sorry? What? Excuse me?

(b) Wh-questions: who, when, where

(c) Partial repetition + wh-question

(d) Partial repetition

(e) You mean + understanding check

When they have finished, answers are checked and students are asked to compare the L1 equivalents to what they have learned.

Part II: Practice Activity: Say that Again?

In the second part, students are asked to talk to at least to two of their classmates about their ideal partner. Before starting, they are told to prepare some notes that they will use in conversations just as in the original activity. While talking with their partners, students are told to use at least three of the above-mentioned asking for repair expressions and answer accordingly. When they have finished, a few groups are selected to make a dialogue for the whole class to hear.

In the three implementations this paper seeks to derive benefits from pragmatics and conversation analysis, two fields in Linguistics aiming to study language in context. To that end, conversational strategies related to opening and closing a conversation, monitoring, turn taking, negotiating meaning and making repairs are considered. As each conversation in every language takes place with the use of such strategies, researchers draw attention to the need to teach language, especially speaking skills, with explicit reference to such pragmatic skills, as well as accurateness and grammaticalness, which are not more important especially in conversation. As well as being universal in terms of being relevant in each language, such conversational strategies are language-specific, meaning that they may serve different purposes and show up in different shapes in different languages. This may result in foreign language learners transferring pragmatic structures from their mother tongue (often mistakenly). Therefore, it is considered important to teach conversational strategies by taking L1 into account and shaping teaching practices accordingly.

The three activities implemented in this paper address these issues. Role plays, awareness raising activities and practice activities consolidating them are suggested. In the activities, initially the pragmatic aspects to be focused are first handled in an explicit way and a small task is carried out by students. Afterwards, they practice what they have learnt. Finally, evaluation procedure follows together with comparison of L1 pragmatic conventions to those of L2.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge Bayram N. Pekoz for inspiring us to publish this work.

Canale, M. and Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 1-47.

Cook, G. (1989). Discourse. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dörnyei, Z. and Thurrell, S. (1991). Strategic competence and how to teach it. ELT Journal, 45(1), 16-23.

Dörnyei, Z. and Thurrell, S. (1994). Teaching conversational skills intensively: Course content and rationale. ELT Journal, 48(1), 40-49.

Færch, C. and Kasper, G. (1986). Strategic competence in foreign language teaching. In G. Kasper (Ed.), Learning, teaching and communication in the foreign language classroom. (pp. 179-193). Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

Oxford, R., Lavine, R. and Crookall, D. (1989).Language learning strategies, the communicative approach, and their classroom implications. Foreign Language Annals, 22(1), 29-39.

Ridgway, T. (2000). Listening strategies—I beg your pardon? ELT Journal, 54(2), 179-197.

Sayer, P. 2005. An intensive approach to building conversation skills. ELT Journal 59/1 2005.

Tarone, E. and Yule, G. (1989). Focus on the language learner. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Willems, G. (1987). Communication strategies and their significance in foreign language teaching. System, 15(3), 351-364.

Wong,J. and Waring, H. Z. (2010). Conversation Analysis and Second Language Pedagogy. Routledge.

Please check the Teaching Spoken English & Grammar course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|