Techniques for Teaching Adolescent Learners

Martin Sketchley, UK

Martin Sketchley is a Young Learner Co-ordinator at LTC Eastbourne, where he is involved in teacher training, observations and syllabus and materials design for the young learner curriculum. He holds an MA in ELT from the University of Sussex. His research interests include Dogme ELT, teacher training and YL teaching and methodology. E-mail: martin.sketchley@ltc-eastbourne.com ,

E-mail: martinsketchley@gmail.com

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

The study

Conclusion

References

Teaching adolescent learners has often been problematic issue, with teachers deciding what to teach based upon reflection with previous successful lessons. However, this article suggests techniques, methods and approaches which could be incorporated in the adolescent English language classroom. The suggestions are based upon the findings from research undertaken with the surveying of 35 teachers in various countries each with differing experiences and/or qualifications with adolescent young learners. The findings from the research suggest an approach which focuses more on speaking and listening rather than grammar which is delivered through a project based approach. Also, it was determined that humour plays an important role in the classroom to lower the affective filter which in turn engages, motivates and interests the adolescent learner. An area which adolescent teachers should consider less suitable would be the teaching of grammar or reading within the classroom.

The teaching of adolescent learners, usually between the ages of 12 to 16, in ELT is widely recognised as the most problematic as well as the most exciting age to teach (Harmer 2007), with these learners having a greater ability for more creative thinking compared to primary counterparts. Furthermore, the demand for language teachers to deliver language courses for adolescent learners is increasing with limited understanding how adolescent courses should be considered. The language course for adult learners is usually to practice language items and study language, whereas the adolescent language learner can be quite challenging with learners requiring more from their teachers. Puchta and Schratz (1993) highlighted that most problems arose with adolescent learners due to the teacher’s inability to understand the learner and respond appropriately with suitable material for future classes. Scrivener (2011) echoes this sentiment with adolescent learners likely to feel more engaged if “they have chosen what to do and how to do it” (p.326).

Teachers of adolescent learners have always adopted a range of strategies and tools to encourage and promote interest within their lessons. These have included the use of technology, games and competitions or project work to develop learner interest and promote a source for language teaching. Furthermore, Egan (2011) also highlighted the growing importance of the ‘body’s toolkit’ to improve adolescent learner engagement, which could include the use of senses, emotions, pattern and musicality as well as humour (p.151-152). The focus is obviously more on the teacher, rather than on the method or process of teaching and strips the teaching back to basics. It is vital for teachers to be more authentic and personal when considering a more humanistic approach to their teaching. Authenticity and autonomy are a great strength towards a more productive and reflective classroom, with teachers striving to develop a more responsive approach with their teaching. However, it is recognised that teachers and learners will often be guided with their teaching or learning due to institutional expectations (Tudor 1996:136). Nevertheless, this study focuses on the private language institute delivering language courses to adolescent learners.

There are various tools, methods and a range of eclectic approaches that adolescent teachers are now able to incorporate within the classroom. These could include video, technology, or role-plays and are also able to select a range of methods such as a task-based approach, project-based teaching, CLIL (which is quite a popular technique in numerous countries for young learners and is now adopted within the English curriculum within Spain) as well as the communicative approach to name just a few. The development towards more humanistic forms of teaching lend well to the teaching of adolescent learners as it is more likely to motivate and be more immediate for these language learners (Harmer 2007). Humanistic forms of teaching are considered more personal and relevant for learners (Puchta and Schratz 1993) with the adolescent learner being central to the learning process (Thornbury 2006). Due to the apparent lack of published research associated with the teaching of adolescent language learners, it was critical that a study was undertaken to assess suitability of teaching techniques and methods. The study aims to establish patterns and approaches to assist with the teaching of adolescent learners.

Background

One of the key objectives for the study was to determine suitable approaches and techniques incorporated in the adolescent classroom. To accomplish this aim, 35 language teachers, from various countries, who had experience of teaching adolescent language learners, were asked to complete an online anonymous survey. To enhance the credibility of the study, it was necessary to create a survey which included closed and open questions as well as scales. The author referred to Borg (2013) and Dörnyei (2010) when creating the survey for the study. When developing the survey, it was piloted with a small selection of teachers at a selected institution and amendments were considered before requesting English language teachers to complete the survey.

Participants

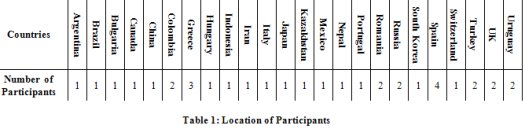

The participants completed the survey that were located in a number of different countries, with 26 participants being female while the remaining 9 being male. Further information regarding the location of participants with the research is detailed in the table below.

Many of the participants, were located in different countries but a few were located within the same country: four participants from Spain, three from Romania, two from Turkey, two from the UK, two from Colombia, two from Uruguay and the remaining participants were all from other countries. Out of the 26 participants being female while the remaining 9 being male. Furthermore, there were only 9 participants who held a Young Learner extension certificate (such as the TYLEC or CELTYL), which does raise questions regarding the lack and appropriateness for credentials when deciding on a career when teaching young learners. Even though, the majority of participants with the study considered the extension certificate as of importance for the delivery of language courses (which is further highlighted within the analysis of survey results), only a select few had a related qualification. Nevertheless, those adolescent teachers which participated with the study had differing years of teaching experience as well as had gained various levels of ELT-related qualifications.

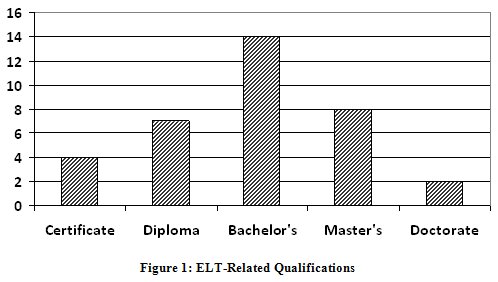

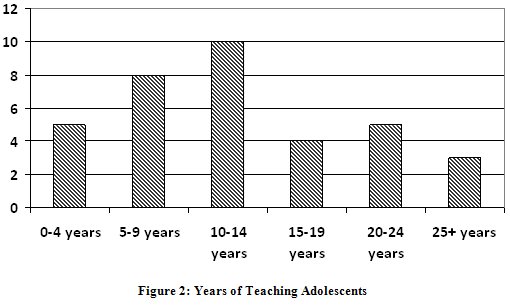

As Figure 1 demonstrates above, most participants had between 10-14 years of adolescent teaching experience, with three having 25+ years of adolescent teaching experience. Furthermore, as Figure 2 below suggests, 14 participants held a Bachelor’s ELT-related qualification, while 8 held a Master’s, 7 with a Diploma, 4 participants held a Certificate and only two held a Doctorate.

It felt a necessary aim, for this study, to gain a broad perspective on the teaching of adolescent learners and, judging from the background of many of the participants, this aim was achieved.

Survey results

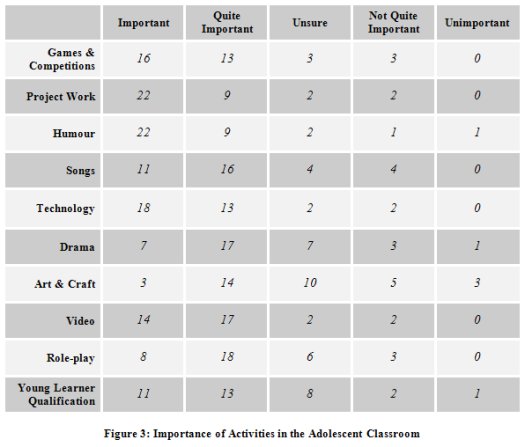

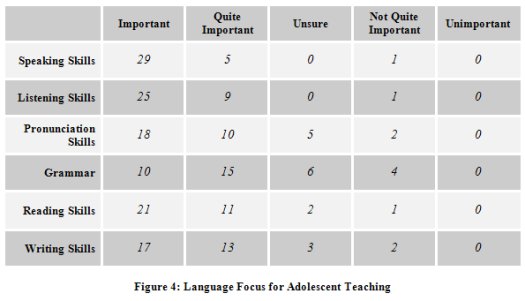

The survey asked adolescent teachers to grade various activities and tools employed within the classroom on a Likert scale: ‘Important’, ‘Quite important’, ‘Unsure’, ‘Not quite important’, or ‘Unimportant’. Likert scales are the most commonly used scaling techniques within questionnaires due to its simplicity and reliability (Dörnyei 2010). Activities or tools which are usually incorporated into the adolescent classroom include games and competitions, project work or role-plays. It was determined necessary to request participants their perceived importance of YL-related qualifications (such as the TYLEC or CELTYL) with the teaching of adolescent learners. The second part of the survey considered perceived importance of teaching various areas of skills and systems of English language with adolescent learners, such as speaking, listening or pronunciation skills. Again, like the previous part of the survey, participants were requested to grade importance of various areas of teaching on a Likert Scale, with gradings, as before, between “Important” to “Unimportant”.

Survey findings

Should teachers wish to deliver English classes which are generally considered important within the ELT profession, it is necessary to consider opinions from other adolescent teachers with what works or what does not work within the classroom. The key classroom activity which teachers considered important for lessons was “Project Work” (22 Important and 9 Quite Important), the integrating of “Technology” (18 Important and 13 Quite Important), “Games and Competitions” (16 Important and 13 Quite Important) as well as the use of “Video” (14 Important and 17 Quite Important). Upon analysis for suitable traits expected with adolescent teachers, humour was considered an integral asset (22 Important and 9 Quite Important). Interestingly, activities which were considered more young learner orientated were generally unsuitable included “Drama” (1 Unimportant and 3 Not Quite Important) as well as “Songs” (4 Not Quite Important). Participants were generally more unsure of the inclusion of “Art & Craft” (10 Unsure) compared to other activities. This is quite significant as project work, in some respects, does include an aspect of creative focus which incorporates the use of art and craft. I suppose art and craft is usually considered more appropriate “with children aged between four and twelve” (Wright 2001:6) rather than adolescent learners.

In reflection to the activities mentioned previously, which focused on a suitable method or approach to deliver the English language curriculum, it is necessary to consider the language focus which should be taught during the aforementioned lesson. The second part of the survey considered appropriate language focus for adolescent teaching.

Due to limited research undertaken within the language focus for the teaching of adolescent learners, it is a requirement to better understand what is generally expected with other language teachers. The primary focus participants expressed as significant for the adolescent classroom should include the teaching or promotion of “Speaking Skills” (29 Important and 5 Quite Important), “Listening Skills” (25 Important and 9 Quite Important) as well as “Reading Skills” (21 Important and 11 Quite Important). With further analysis, “Grammar” (10 Important and 15 Quite Important) was the least expected focus for adolescent classrooms with four participants suggesting that it was “Not Quite Important”. Interestingly, “Writing Skills” was considered less important to include within the adolescent classroom, as this corresponds with the acknowledgement that the teaching of grammar, which is more associated with the written production of language, is less important than say speaking and listening.

The English language classroom is an environment which should motivate and encourage learners to develop their language skills. How this is achieved has always been a controversial, especially for adolescent language learners. The findings from the research highlight the need for adolescent language teachers to adopt methods, for delivering language courses, which should focus on speaking and listening skills. Speaking and listening skills with teenaged learners should be encouraged through the use of project work, technology as well as games and competitions. If considered further, the skills of speaking and listening could be related to conversation: a similar principle to Dogme ELT, which is associated more with the humanistic area of teaching. Humour, however difficult to define, is obviously an important trait for the classroom which should be exploited by teachers and should be included within YL teacher training and development courses. Furthermore, humour is closely related to humanism and would assist in lowering the adolescent learner’s affective filter, which would then develop learner interest in the classroom. In conclusion, it would be recommended for teachers, to maintain adolescent learner interest and motivation with their language learning, to incorporate a range of techniques as highlighted within the research. Otherwise, learners will have the potential to lose interest during lessons should teachers decide to go with the familiar and not deviate from the predictable.

Nevertheless, the study is an important step forward to better understand the adolescent classroom and suitable or less suitable methods or approaches. It is also crucial to determine how language is delivered during lessons. Unfortunately, only takes into account the teacher opinion, rather than the adolescent learner viewpoint. Future studies could inquire about learner opinion and develop a more sophisticated understanding of lesson expectations. Furthermore, additional studies could incorporate a more balanced study with teacher as well as student interviews. Notwithstanding, this study is a wonderful first step towards better understanding the adolescent learner and classroom which considers the opinion of various teachers located around the world.

Borg, S. 2013. Teacher Research in Language Teaching: A Critical Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dörnyei, Z. 2010. Questionnaires in Second Language Research: Construction, Administration, and Processing (Second edition). Oxon/NewYork: Routledge.

Egan, K. 2011. ‘Teaching Young Learners: cognition, curriculum and culture’, IATEFL 2010: Harrogate Conference Selections, Pattison, T (ed). Canterbury: IATEFL.

Harmer, J. 2007. The Practice of English Language Teaching. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Puchta, H. and Schratz, M. 1993. Teaching Teenagers. London: Longman.

Scrivener, J. 2011. Learning Teaching: The Essential Guide to English Language Teaching. Oxford: Macmillan Education.

Thornbury, S. 2007. An A-Z of ELT: A Dictionary of Terms and Concepts. Oxford: Macmillan Education.

Tudor, I. 1996. Learner-centredness as Language Education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wright, A. 2001. Art and Crafts With Children. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Building Positive Group Dynamics course at Pilgrims website.

|