Differentiated Reading and Writing Instruction with Technology

Cindy Chia-Hui Shen, Taiwan

Cindy Shen obtained her Master degree from the Department of English Instruction in Taipei Municipal University of Education, and now she is a PhD student at the Department of English, National Taiwan Normal University. She teaches at Taipei Municipal Fuan Elementary School. Her research interests include SLA, reading strategies, and computer-assisted language learning. E-mail: cindy422@tp.edu.tw

Menu

Introduction

Technology supports differentiated instruction

Content

Process

Product

Closing thoughts

References

Storybooks

Currently, the emergence of mobile technologies such as tablet PCs in language classrooms, particularly in elementary schools, is bringing new possibilities to language learning and literacy development. The state-of-the-art technological devices, such as tablet PCs, have created excitement for their potential to be used as instructional tools for literacy education. Tablet PCs have become a powerful instructional tool for both educators and students to read and write stories (Robin, 2008). However, one of the most difficult challenges for teachers is reaching the needs and language proficiency of an increasingly diverse student population. In order for teachers to reach all students, teachers must begin where students are, which means recognizing individual differences with differentiated instruction.

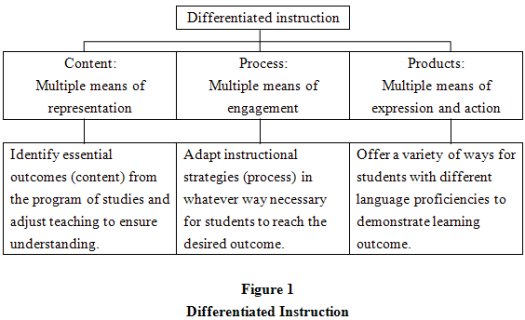

Differentiated instruction with the use of technology offers the opportunity for teachers to engage individual student in different modalities, while also varying the type of instruction, complexity levels, and teaching strategies. Tomlinson (2006) identifies three elements of the curriculum that can be differentiated: Content, Process, and Products (Figure 1). Teachers can differentiate content, process, and product according to student’s readiness, interests, and learning profile through a range of instructional and management strategies. So far very little attention has been paid to see how mixed ability learners grouped for differentiated instruction with the support of technology can be implemented in the language classrooms.

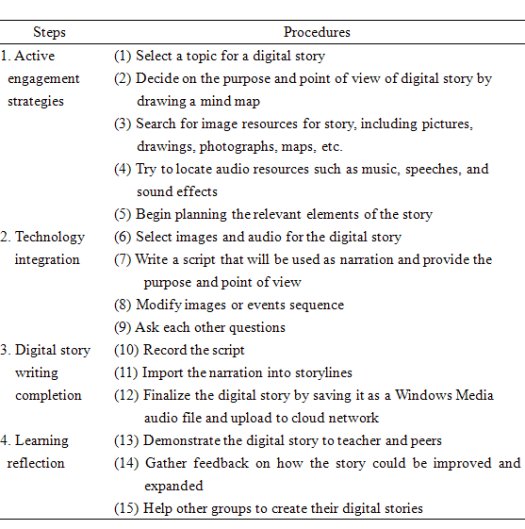

Based on Tomlinson’s (2006) classification of modified elements in differentiated instruction, i.e., content, process, and product, the practical activities that teachers can use are presented as follows.

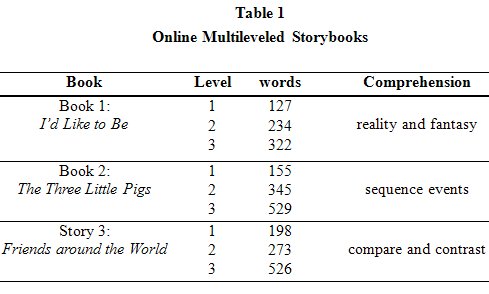

The online storybooks are from Reading A-Z www.readinga-z.com. It is a PreK-6 educational resource company specializing in online delivery of leveled readers and supplementary curriculum. It is challenging for teachers to take care of mixed level students in one class at the same time. The great advantage of this online reading resource is because of its multileveled storybooks, which can meet students’ individual needs and current language proficiency level.

For teachers, there are three main criteria for selecting appropriate storybooks in teaching. First, the storybook should be a fiction with sufficient story elements, including plots, characters, setting, problems and solutions; therefore, students can easily collaborate, discuss, and share their comprehension skills and reading strategies within groups or with the whole class. Second, there are three levels for animated storybooks, with each sharing similar content and vocabulary. Third, the book whether it is at the beginning, intermediate, or advanced level is about 120 to 530 words in length, which make it possible not only for the students in different levels to complete their own digital story reading and writing, but also for the teacher to conduct the post-reading discussion within the 40 minutes time frame of a class period.

Based on the selection criteria, three storybooks are selected: I’d Like to Be, The Three Little Pigs, and Friends around the World (see Table 1). The word range for each level is 100-200 for the beginning level; 200-350 for the intermediate level, and 300-550 for the advanced level. The children are exposed to a total of three books across six weeks, one book for two weeks.

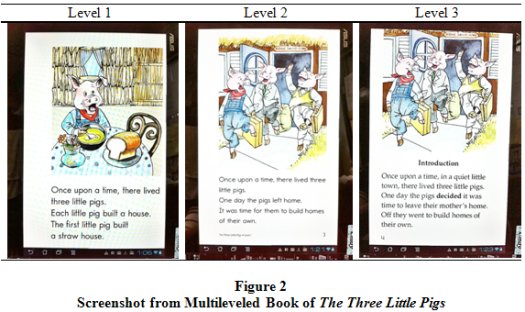

Take Story 2 The Three Little Pigs as an example, the same story is total at three different reading levels, i.e., Level 1, 155 words; Level 2, 345 words; Level 3, 529 words. The screenshot of the first page from each level is presented in Figure 2.

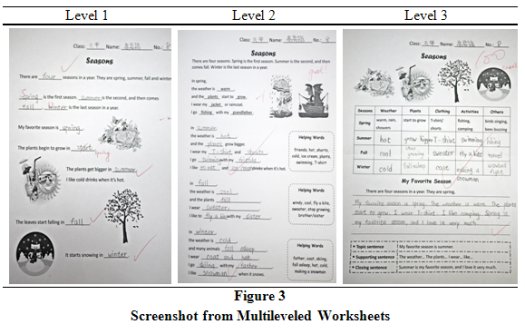

Teachers design a set of three-leveled worksheet with the same theme, e.g., season. Each student is equipped with their own personal tablet PC for searching new information or look up the online dictionary or translation. An ongoing, formative assessment is conducted. Teachers continually assess to identify students’ strengths and areas of need so that they can meet students where they are and help them move forward.

Level 1 is the basic level, focusing on target words such as spring, summer, fall and winter. All of the students are given level 1 worksheet and finish the worksheet individually. As long as the student finishes level 1 worksheet, he or she gives it to the teacher for correction, and then gets the level 2 worksheet. According to Boyd-Batstone (2004), teachers make a record as formative assessment in differentiated instruction. Moreover, only 50% of the students have the chance to get the level 2 worksheet, which focuses on filling in the words or phrases in the sentence contexts. For example, fly a kite, shorts, swimming, cold, etc.

As for the most advanced level worksheet, students not only need to use their memory from the previous two worksheets for completing the grid, but also need to write a short paragraph about their own favorite season (see Figure 3). However, only 33% of the students have the chance to get the level 3 worksheet. This activity is timed by using the online stopwatch www.online-stopwatch.com /large- stopwatch/. In brief, each student can reach the same goal of learning the same theme but in different process based on their proficiency levels. Ongoing assessments enable teachers to develop differentiated lessons that meet every student needs (Bates, 2013).

One online storybook We’re Going on a Bear Hunt (Rosen, 1997) is selected based on three criteria. First, the storybook has accumulative, repetitive, and predictive structures so students could develop memory skills, produce their own storylines, and build oral confidence. Second, the book is 414 words in length, which make it possible for the teachers to complete the pre-reading discussion and story reading within the 40 minutes time frame of a class period. Third, the storybook is interesting and comprehensible and is filled with rich language and colorful illustrations. Each student is given a tablet PC to read this online storybook individually.

To demonstrate the impact of digital story reading and writing in students learning, the teachers guide their students to read the online storybooks with audio support, word-by-word tracking, and picture animation. Teachers also show students options to mark and highlight the text by tapping the screen, look up online dictionaries, and ways to record audio to e-book and replay their oral reading. They can also insert or remove notes, mark up e-book pages, attach files, and add comments. After that, students need to revise and write stories by using their own tablet PCs in the wireless campus environment.

A four-step method is adopted and revised from Robin’s (2005) approaches for constructing digital stories, and is generated based on Barrett’s (2006) student-centered learning strategies. First, students select a topic and used a free website to draw mind maps called text 2 mind map www.text2mindmap.com to draw the outline of their groups’ story after reading an online storybook. A story map is designed to illustrate the main components of the story and their relationship to the overall narrative. Next, students research for information on the topic to write a logical story or sequence of events. After completing the scripts, they question each other, engaging in peer critiquing or coaching.

After peer feedback, students arrange the sequence of scenes, sound effects, and other digital components. Each task from the pre-production phase to the final distribution phase is all tablet-PC-based. This requires students to focus on the content as well as multimedia elements. Finally, students present their stories in a storyboard format (see Table 2 for summary of the procedures).

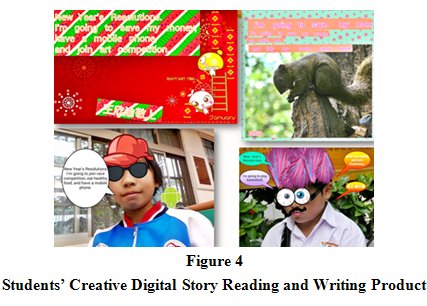

In total, each class is exposed to one book across four weeks of the project. Thus, students need to work in groups and create one digital story. One example from the young EFL learners’ digital story reading and writing product is demonstrated as Figure 4.

The goal for differentiated instruction is to make every student engage in learning and achieve the same objective with confidence and enjoyment. With technical facility support, especially personalized tablet PC, it creates powerful benefits in conducting differentiation. Teachers are encouraged to create motivating assignments that meet students’ diverse needs and individual differences to maximize their language learning at the early ages (Johnston, 2003).

Barrett, H. (2006). Convergence of student-centered learning strategies. Technology

and Teacher Education Annual, 1, 647-654.

Bates, C. C. (2013). How do wii know: Anecdotal records go digital. The Reading

Teacher, 67(1), 25-29.

Boyd-Batstone, P. (2004). Focused anecdotal records assessment: A tool for

standards-based, authentic assessment. The Reading Teacher, 58(3), 230-239.

Johnston, P. (2003). Assessment conversations. The Reading Teacher, 57(1), 90-92.

Robin, B. (2005). Educational uses of digital storytelling. Main directory for the educational uses of digital storytelling. Instructional technology Program. University of Huston. www.coe.uh.edu/digital-storytelling/default.htm.

Robin, B. (2008). Digital storytelling: A powerful technology tool for the 21st century classroom. Theory Into Practice, 47, 220-228.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2006). How to Differentiate Instruction in Mixed-Ability

Classrooms. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Rosen, M. (1997). We’re Going on a Bear Hunt. London: Walker Books.

The Three Little Pigs:

Level 1 www.readinga-z.com/books/leveled-books/book/?id=1293

Level 2 www.readinga-z.com/books/leveled-books/book/?id=1205

Level 3 www.readinga-z.com/books/leveled-books/book/?id=1208

Please check the Using Mobile Technology course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the ICT - Using Technology in the Classroom – Level 1 course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the ICT - Using Technology in the Classroom – Level 2 course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|