To Be(come) or Not to Be(come)

Cesar Elizi, Brazil

Cesar Elizi is a PhD student at UNICAMP and a professor at FACAMP, Brazil. His interests include Metacognition, L2 Aptitude and Identity.

E-mail: elizi.cesar@gmail.com

Menu

Introduction

Q methodology

The acquisition of vocabulary

Theories of Self

Putting it all together

Conclusions

References

In Know Thy student (Elizi, 2009), the ancient inscription from the Delphic Oracle was subtly modified by replacing ‘Self’ with Student in an attempt to shed some light on the need to know students as whole persons. The aim of this article is to approach a more elusive, but not less important, dimension of knowing our students using a personal recollection. In order to do this, I shall briefly introduce Q Methodology.

The question ‘What is a Self?’ was neglected by Psychology in the first decades of the 20th century, mainly due to an unfortunate adherence to the type of objectivity pursued in Physics and the hard sciences. Nevertheless, the concept of Self remains central to any understanding of what it is that constitutes us as Humans. If a field of research is to be fruitful in this enterprise, it must take Human experience, with its inherently subjective perceptions and feelings, as its fundamental building block. Phenomenology is our best candidate since it opens windows to Human experience by means of thought listing, protocol analysis and introspective reports (Taylor et.al., 1994).

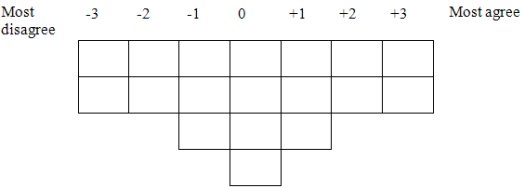

In a nutshell, Q is a research method in the post-strucuralist tradition that aims to investigate how people view a certain topic (McKeown & Thomas 2013), how they approach an issue, how similar their point of view is, and most importantly, what lies beneath this similarity. Firstly, the researcher gathers samples of discourse from the community to be studied, via focus groups, for instance. From this, a set of statements about the topic is construed, reflecting the variety of opinions, feelings and valuations about the topic. These are printed on cards and each individual is asked to rank the statements according to a condition of instruction, which typically reads “Rank the statements from ‘most agree’ to ‘most disagree’”. This is done on an inverted bell-shaped grid:

The completed grids are inserted into a computer software package to perform the statistical procedure, basically involving Factor Analysis (Bachmann 2004). This procedure reveals “constellations” of people who share, to some extent, their viewpoint about the topic. The groups are labelled and described according to what surfaces as the unifying elements behind their grouping, thus revealing the shared point of view, or subjectivity.

Recently I attended a colleague’s presentation of her PhD thesis (Sartori, 2013) on students’ and teachers’ perceptions about the acquisition of lexis using Q methodology (Watts & Stenner, 2012).

At some point she mentioned that one of her subjects had described a ‘powerful insight’ while taking part in the study and I knew she was talking about me. From that moment on I started to recall our conversation and what went on my mind, to the best of my knowledge, is the following:

I had ranked around 50 cards with statements describing different perceptions and feelings about the acquisition of vocabulary and I indeed described my experience of participating in the study as powerfully insightful. I was amazed at how much better I felt I could understand my own process of learning English vocabulary. Being a PhD student myself, I thought it was awkward that such a simple task could have such a profound impact on my knowledge of my own English learning history. However, at the same time I had a strange sensation that nothing had changed.

I then formulated three hypotheses: the task had either (1) deepened my own understandings, (2) helped me structure these understandings, or (3) somehow brought them to new light. None of these echoed inside me because I felt that participating in her research had not given me anything I did not already have.

Cavell discusses the role of memory in the construction of the notion of Self and how reporting on mental states is not always straightforward:

“Not all activities of the mind are ones for which ‘I’ can speak” (2006:19)

Indeed, we often experience sensations that we cannot put in words and so do our students.

Addressing the definition of subjectivity, Zahavi (1994) uses Husserl’s Phenomenology as a starting point to defend the idea that the Self as an experiential dimension is both more fundamental than and a presupposition of the narrative Self in a way not entirely different from the action of participating in a group’s communal discourse surrounding a topic:

Who one is depends on the values, ideals, and goals one has: it is a question of what has significance and meaning, and this, of course, is conditioned by the linguistic community to which one belongs (Zahavi 2008: 40)

In other words, first there are experiences of mental states, not all of which can be reported. Then, by means of reflection, and frequently aided by social interaction, those mental states are connected and sequenced in a way that gives rise to a sensation of continuity of experience, as a form of fiction. In turn, by means of this fiction, the “author” comes to life:

This narrative, however, is not merely a way of gaining insight into the nature of an already existing Self. On the contrary, the Self is the product of a narratively structured life (Zahavi 2008:1420)

I now believe the follow up interview helped me string perceptions and feelings regarding my vocabulary learning history into a somewhat coherent whole. It is not that they did not exist before. They were not unstructured. Neither were they unconscious. And yet, I felt able to reflect on my acquisition of lexis with a sense of clarity I did not possess before.

Those perceptions and feelings were in fact in my mind. Only they had not yet become my experiences, my feelings. They were then not mine in a sense that they now are. The ‘I’ in “I learned vocabulary in this and that way” came to be exactly by doing something, by actively participating in a dialogue with the perceptions and feelings of others and stringing them together around a coherent narrative. This is operant subjectivity as captured by Q methodology. I strongly suggest the interested reader have a go at the exceptionally clear book by Watts and Stenner (2012) in order to learn more about this powerful, albeit still undervalued, research methodology.

We teachers are often trying to get to know students well in order to better help them in the learning process. In our attempt to do this, we struggle to grasp the meaning of students’ behaviour. What this discussion of the concept of Self might offer us is a reminder that

There are not meanings, but people meaning things by what they say and do (Cavell 2006:64)

This is why the L2 classroom is not only a place for activities focussed on atomised linguistic features, but rather a space for personal development, self-discovery and self-construction. It is the student as a person we should focus on, someone who is constantly getting to know more about themselves, and in so doing, become themselves.

Bachman, L.F. Statistical Analyses for Language Assessment. (2004) Cambridge University Press.

Cavell, M. Becoming a subject: Reflections in Philosophy and Psychoanalysis. (2006) Oxford University Press.

Elizi, C. Know Thy Student. (2009) Humanising Language Teaching. 11:1(February)

McKeown, B. & Thomas, D. Q Methodology. London: Sage, 2013.

Saartori, A. "Percepções de Alunos e Professores de ILE Sobre Aprendizagem de Vocabulário: Um Estudo Q". PhD thesis. UNICAMP, 2013. (Students’ and Teachers’ perceptions on EFL Vocabulary Acquisition: a Q study).

Taylor, P., Delprato, D.J. and Knapp, J.R. Q-Methodology in the study of child phenomenology. (1994). The Psychological Record. Vol. 44(2)

Watts, S.; Stenner, P. Q Methodological Research: Theory, Method & Interpretation. (2012). SAGE.

Zahavi, D. Subjectivity and Selfhood: Investigating the First-Person Perspective. (2008) MIT Press. References to this book are in the format of the position in the e-reader Kindle.

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Building Positive Group Dynamics course at Pilgrims website.

|