Let Me Not To the Creations of Young Minds Admit Impediments

Rebeca Duriga, Poland

Rebeca Duriga is a teacher currently working with a variety of levels, class types and age groups at British Council Warsaw, having previously translated and taught at International House Bucharest and Wrocław. She has a degree in English and History and completed both her initial and high-level EFL qualifications quite successfully. Her professional interests are discourse analysis, purposeful use of literature and video in the classroom, extensive reading and innovative ELT materials design. E-mail: biancaledonia@gmail.com

Menu

Introduction

Romeo and Juliet (B1-C1)

Hamlet (B2-C2)

Outcomes

Conclusions

References

Not that many moons ago I was but one of countless students poring over sacred Shakespearean texts in dry academic fashion. Read a sonnet or a play, go over its 'official' interpretations, write about how perceptive said interpretations are, submit tragically unoriginal essay, momentarily rejoice over good grade, and repeat. Ad infinitum. So when I was recently asked by school management to whip up 90-minute workshops aimed at (re)familiarising Young Adult students across Poland with two Shakespearean plays in celebration of the 400th anniversary of the Bard's death, I dreaded the thought of it. Despite my love for literature being very much alive, I feared I would kill any trace of enthusiasm the participants might have for the world's greatest dramatist by teaching Shakespeare the same way he was taught to me.

Still, as there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of by conservative institutions' teaching philosophy, I set about the project with reinvention in mind. And then it came to me: what if reinvention is exactly what I should guide students towards? Would the master of wit truly mind young creative minds playing with what he produced, as one who loved to constantly play with words and worlds, allusions and illusions, conventions and contentions himself?

Without any further ado, here are some highlights of the two workshops.

The main goals of these selected activities are to expand lexical repertoire and encourage collaborative creative writing and use of unorthodox language in the context of producing Shakespearean-like text.

- Learners listen to the Shakespeare song (www.youtube.com/watch?v=65Cy4-rfd24) and answer the questions 'What is the song's message?' and 'How many times is Shakespeare mentioned?'

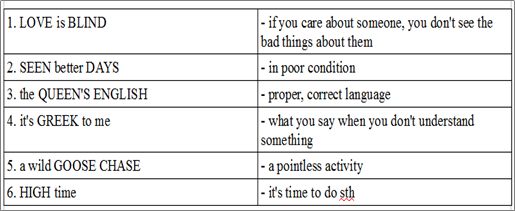

- Students fill in the missing words in the Shakespearean phrases (answers in Figure 1) they heard in the song.

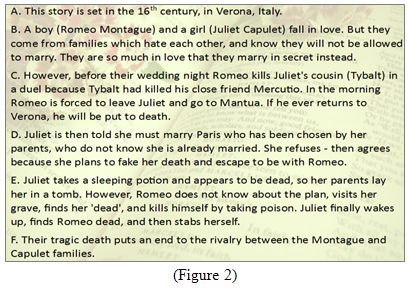

- Students put the play synopsis cards in order. Figure 2 shows the full summary.

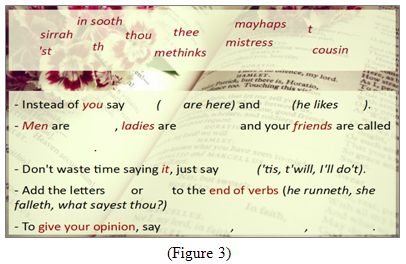

- Crash course in talking like Shakespeare (Figure 3): the teacher has the students fill in the gaps, gives further clarification then does pronunciation work.

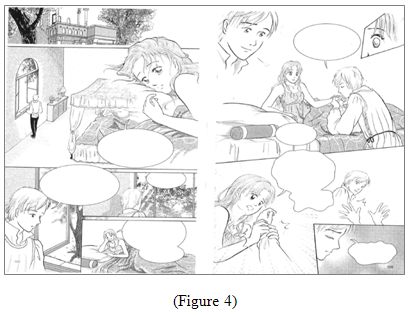

- Students are shown two scenes from the Manga edition of Romeo and Juliet with the dialogue blanked out (Figure 4 shows the first page), then asked to come up with their own dialogue for them using some Shakespearean vocabulary and to practise acting it out. The teacher monitors and assists.

- Groups of three students (as there is an extra character in the scenes) act out their dialogue and vote for the saddest and funniest one as well as the best acting performance. An 'Oscar award ceremony' follows.

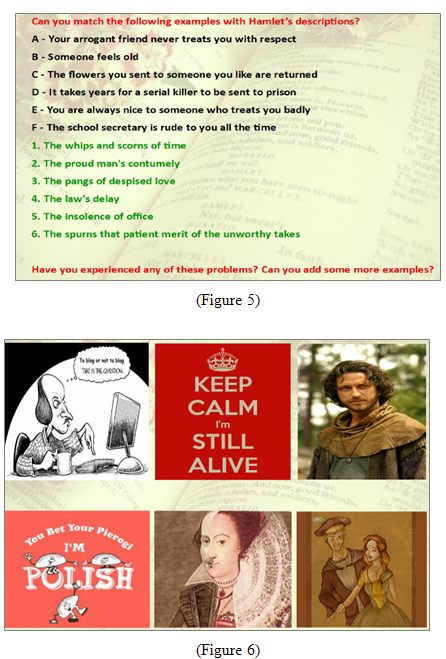

As above, the goals of the final stage are to encourage peer collaboration and use of creativity in producing Shakespearean-like text. After some vocabulary work (Figure 5), students come up with a 'What if …' story based on their own or one of the teacher's ideas (Figure 6: What if Hamlet had lived in the 21st century / hadn't died / had been a commoner / Polish or another nationality / a woman?) and create a dialogue between 'their' Hamlet and another play character.

I am always impressed by how all the students, not just the histrionic ones, put so much of themselves into the performances and make imaginative use of Shakespearean vocabulary, e.g.

- 'In sooth, thy face has seen better days. Mayhaps love is not blind after all', says Juliet rejecting Romeo.

- 'Why are thou leaving me?' asks a despondent Juliet. 'Because thy father is Greek to me!', Romeo retorts.

Learners have also pictured Hamlet talking to himself in Sméagol / Gollum manner, a regretful Prince of Denmark travelling with Doctor Who across time and space to try and rescue Ophelia, Hamlet conversing with a modern-day psychologist after learning Claudius is actually his father, and the protagonist waking up to realise / fantesise it was all a dream (Inception-style).

Feedback has been overwhelmingly positive. Out of 226 participants we have had so far, the majority (211) rated their creative output as the most enjoyable lesson stage and made comments such as:

'Writing your own comic and the acting were the best. Actually, best English lesson I've ever had.' (Oskar)

'Playing “in theatre” was great.' (anonymous)

'I liked everything but I enjoyed the scenes the most.' (Aleksandra)

'The lesson was entertaining and I could show my own creativity, something we don't really do in school.' (Joanna)

'I never liked Shakespeare until now. And I can't believe my team won an Oscar!' (anonymous)

'I definitely enjoyed the acting the most. We made up a completely new [Hamlet] story and I think we did a really good job. Shakespeare would be proud of us.' (Kasper)

In the words of Ben Crystal (2008:32), perhaps it is time we broke a few or all of 'the official commandments of Shakespeare:

You Cannot Change Any Of The Words

He Must Not Be Translated

He Must Be Performed A Certain Way

He Must Be Spoken A Certain Way

He Must Be Spoken Of A Certain Way.'

Yes, he was a genius but also human. 'Just like Einstein – who drank, partied, wore shabby clothes and worried about wars – was human. And Shakespeare didn't write so that 379 years after his death people would be preserving his works in vacuum-sealed bags and I'd be sitting in an exam hall trying to explain the existentialist viewpoint in his plays.' (Ibid:35)

My own experiments with activities that remove the 'sacrosanct therefore unalterable' label off literature by exploiting students' own (re)interpretations of it have shown me their threefold advantage: they provide lessons with much needed emotional colour, prompt learners to use language quite creatively, and tempt them into 'reading on, reading more and reading more into' (Carter & Long 1991:6) texts previously deemed dry and dreary. Enough to make Shakespeare very proud indeed.

Carter, R. & Long, M. (1991) Teaching Literature. Essex: Longman.

Crystal, B. (2008) Shakespeare on Toast. Cambridge: Icon Books.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English Language Improvement for Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English Language Improvement for Adults course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

|