Frames and Reframing

Gabriel R. Scuiu, Romania

Gabriel R. SUCIU is a sociologist. He is interested in NLP and creativity. He has written two books – “Erving Goffman and the Organizing Theories” (2010) and “Introduction to Neuro-Linguistic Programming” (2015) – and some articles like: “Multiple Intelligences” (2011).

E-mail: gabriel_remus_suciu@yahoo.com, gabriel.suciu@ymail.com

Menu

Introduction

First insights from the universal literature

The practice in the American psychotherapy

Frame: boundary, map or territory?

Reframing: the first generation of NLP practitioners

Reframing: the second generation of NLP practitioners

Universal panacea

Conclusion

References

There is a deep rooted belief that mathematics is an inexhaustible source, and a model, for other sciences, including psychology and sociology. But, in this article, I will show that literature, also, can be an inexhaustible source and a model for sciences. And I will leave for another occasion to show that the two beliefs, actually, are the front and the reverse sides of the same coin...

In the followings I will present the career of the ”frame” and “reframing” concepts: as a first insight in literature, they were then taken over by unconventional therapists into their practices; and, then, further, they generated disputes until they became institutionalized instruments, and - ultimately - they finished as a universal panacea regardless their real nature.

Below there are three examples, that I called “snapshots”, from the works of three authors that the current system of libraries classifies them as “children's literature”. Probably because the things these books present are so clear and easy to understand. However, probably they hide deeper truths than the so-called “adults’ literature” which are, sometimes, presented in a language that is coded and hard to understand.

The first example refers to a poem that the White Rabbit reads before the King of Heart’s court, a court that is trying to sentence and execute the Knave of Heart. This could become real only and only if the poem’s content makes sense. And Alice is reframing the whole story saying that the poem has no meaning what so ever, a fact confirmed by the King of Heart.

The second example presents Tom Sawyer who was punished by Aunt Polly to whitewash the fence surrounding the house. But Tom is reframing this punishment (read “this work”) into an entertainment (read “that pleasure”) so that all the children from the village participate in it. And to participate in, they even give all sorts of gifts to Tom.

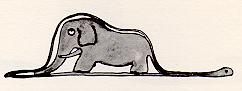

The last example shows two drawings - drawing number 1 and drawing number 2. Their author is a child who wants to express something that would frighten even the adults – namely, a boa constrictor snake that swallowed an elephant, and is slowly digesting it. But the first drawing shows things from the outside, such they resemble a hat. And the laughs of adults, caused by this drawing, only freeze when the things are shown from the inside, in the second drawing, presenting the elephant inside the boa.

First snapshot – Carroll Lewis (1865): “Alice in Wonderland”, pp.63-64

“These were the verses the White Rabbit read:

They told me you had been to her,/ And mentioned me to him:/ She gave a good character,/ But said I could not swim.

He sent them word I had not gone/ (We know it to be true):/ If she should push the matter on,/ What would become of you?

I gave her one, they gave him two,/ You gave us three or more;/ They all returned from him to you,/ Though they were mine before.

If I or she should change to be/ Involved in this affair,/ He trusts to you to set them free,/ Exactly as we were.

My notion was that you had been/ (Before she had this fit)/ An obstacle that came between/ Him, and ourselves, and it.

Don’t let him know she liked them best,/ For this must ever be/ A secret, kept from all the rest,/ Between yourself and me

That’s the most important piece of evidence we’ve heard yet, said the King, rubbing his hands; so now let the jury…>

If any one of them can explain it, said Alice, (she had grown so large in the last few minutes that she wasn’t a bit afraid of interrupting him) I’ll give him sixpence. I don’t believe there’ an atom of meaning in it.

The jury all wrote down on their slates, She doesn’t believe there’s an atom of meaning in it, but none of them attempted to explain the paper.

If there’s no meaning in it, said the King, that saves a world of trouble, you know, as we needn’t try to find any. (…)”

Second snapshot – Mark Twain (1876): “The adventures of Tom Sawyer”, p. 30

“Hello, old chap, you got to work, hey?

Tom wheeled suddenly and said:

Why, it’s you, Ben! I warn’t noticing.

Say – I’m going in a swimming, I am. Don’t you wish you could? But of course you’d druther work – wouldn’t you? Course you would!

Tom contemplated the boy a bit, and said:

What do you call work?

Why ain’t that work?

Tom resumed his whitewashing, and answered carelessly:

Well, maybe it is, and maybe it aint. All I know, is, it suits Tom Sawyer.

Oh come, now, you don’t mean to let on that you like it?

The brush continued to move.

Like it? Well I don’t see why I oughtn’t to like it. Does a boy get a chance to whitewash a fence every day?

That put the thing in a new light. Ben stopped nibbling his apple. Tom swept his brush daintily back and forth – stepped back to note the effect – added a touch here and there – criticized the effect again – Ben watching every move and getting more and more interested, more and more absorbed. Presently he said:

Say, Tom, let me whitewash a little.

Tom considered, was about to consent; but he altered his mind:

No – no – I reckon it wouldn’t hardly do, Ben. You see, Aunt Polly’s awful particular about this fence – right here on the street, you know – but if it was the back fence I wouldn’t mind, and she wouldn’t. Yes, she’s awful particular about this fence; it’s got to be done very careful; I reckon there ain’t one boy in a thousand, maybe two thousand, that can do it the way it’s got to be done.”

Third snapshot – Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (1943): “The Little Prince”, p. 4

“Once when I was six years old I saw a magnificent picture in a book, called True Stories from Nature, about the primeval forest. It was a picture of a boa constrictor in the act of swallowing an animal. Here is a copy of the drawing.

In the book it said: Boa constrictors swallow their prey whole, without chewing it. After that they are not able to move, and they sleep through the six months that they need for digestion.

I pondered deeply, then, over the adventures of the jungle. And after some work with a colored pencil I succeeded in making my first drawing. My Drawing Number One. It looked like this:

I showed my masterpiece to the grown-ups, and asked them whether the drawing frightened them.

But they answered: Frighten? Why should any one be frightened by a hat?

My drawing was not a picture of a hat. It was a picture of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant. But since the grown-up were not able to understand it, I made another drawing: I drew the inside of the boa constrictor, so that the grown-ups could see it clearly. They always need to have things explained. My Drawing Number Two looked like this:

So, after I presented the concept of reframing in the universal literature – namely, at Lewis Carroll, Mark Twain and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry – I will present the same concept in the American psychotherapeutic practice – especially at Virginia Satir, Milton Erickson and Paul Watzlawick.

Opening the brackets, Paul Watzlawick (Watzlawick, Weakland & Fisch, 1974) and Virginia Satir's exegetes (Andreas 1991) make explicit reference to the book “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer”. Also, Paul Watzlawick makes reference to numerous pages from “Alice in the Wonderland” (Watzlawick, Bavelas & Jackson, 1967). Or it is known that both Paul Watzlawick and Virginia Satir – along with Milton Erickson – were part of the same intellectual circles: so they had many opportunities to talk about these books before writing about them, and inspire others to write about them. (And much later, new generations of authors have written how the book “The Little Prince” could be read through the lenses of the Invisible College [Karam, 2009]). These being said, I close here the brackets.

Knowing these, Virginia Satir presents, in one of her books, a case in which a boy has stolen thirteen cars. And the therapist interprets this behavior not as a vice, but as a skill, predicting for the boy a successful future as engineer. In his turn, Milton Erickson describes the case of his three years boy – Robert – who felt down the stairs, and was bleeding abundantly. Instead of being scared watching the boy full of blood, Milton and his wife began to wonder how “red, good and powerful” was the blood of their son: so, instead of pain and fear, they install feelings of pride and courage in the heart of the toddler. Finally, Paul Watzlawick tells the story of a man who has stammering and, in spite of it, he earned his living in sales. Being different from other salesmen who were flooding their customers with information, this man gained the confidence of its customers through stammering, presenting the information piece by piece.

From: Virginia Satir (Satir, Banmen, Gerber & Gomori, 1991: 263):

“I had a family in which the boy had stolen a car. As I worked with the family, it turned out he had actually stolen thirteen cars. I said, My goodness, how did you get these cars going? And he told me how he would fix this wire and fix that wire, and so on. He became involved. I was now connected. He seemed to feel more appreciated.

You know what? You already have the makings of an engineer. I also knew his father was an engineer. Now all you need to do is take your marvelous engineering skills and learn to apply them differently.”

From: Milton Erickson (Rosi, 1980: 176-179, Battino, 2002: 202-203):

“Erickson (…) described an incident in which his son Robert, then three years old, fell down the back stairs. Erickson did not try immediately to move the screaming boy, who lay sprawled in agony on pavement spattered with blood from his profusely bleeding mouth. Instead, he waited for the boy to take the fresh breath he needed to scream anew and then acknowledged in a simple and sympathetic fashion the awful and terrible pain Robert was experiencing. By demonstrating this understanding of the situation, Erickson secured rapport and attention, which he then consolidated by commenting that it would keep right on hurting. He paced further by voicing aloud the boy’s desire to have the pain ease, then led by raising the possibility (not the certainty) of the pain diminishing within several minutes. He next distracted Robert by closely examining with his wife the awful lot of blood on the pavement before announcing that it was good, red, strong blood and suggesting that the blood could be better examined against the white background of the bathroom sink. By this time, absorption and interest in the quality of his blood had replaced Robert’s pain and crying. This was utilized to demonstrate repeatedly to the boy that his blood was so strong and red that it could make pink the water being poured over his face. Questions of whether the mouth was bleeding and swelling properly were then raised and, after close examination, answered affirmatively. The potentially negative response to the next step of stitching was paced before Erickson regretfully informed Robert that he probably couldn’t have as many stitches as he could count or as many as several older siblings. This focusing of Robert’s attention on counting the number of stitches served indirectly to secure freedom from pain. Robert was disappointed when he received seven stitches, but cheered some when the surgeon pointed out that the stitches were of better quality than those given his siblings and that they probably would leave a W-shaped scar similar to the letter of his Daddy’s college”

From: Paul Watzlawick (Watzlawick, Weakland & Fisch, 1974: 94-95):

“For reasons irrelevant to our presentation, a man with a very bad stammer had no alternative but to try his luck as a salesman. Quite understandably this deepened his life-long concern over his speech defect. The situation was reframed for him as follows: Salesmen are generally disliked for their slick, clever ways of trying to talk people into buying something they do not want. Surely, he knew that salesmen are trained to deliver an almost uninterrupted sales talk, but had he ever really experienced how annoying it is to be exposed to that insistent, almost offensive barrage of words? On the other hand, had he ever noticed how carefully and patiently people will listen to somebody with a handicap like his? Was he able to imagine the incredible difference between the usual fast, high-pressure sales talk and the way he would of necessity communicate in that same situation? Had he ever thought what an unusual advantage his handicap could become in his new occupation? As he gradually began to see his problem in this totally new – and, at first blush, almost ludicrous – perspective, he was especially instructed to maintain a high level of stammering, even if in the course of his work, for reasons quite unknown to him, he should begin to feel a little more at ease and therefore less and less likely to stammer spontaneously”

Milton Erickson knew closely Virginia Satir and Paul Watzlawick. These two, mentioned latter, were part of the Invisible College known as the Palo Alto School. This school has followed, closely, the work of a visionary named Gregory Bateson. In turn, Gregory Bateson had influence on younger generations of either sociologists or psychologists, among which Erving Goffman, Richard Bandler, John Grinder, or Robert Dilts. Therefore the work of Gregory Bateson was the spark that set in motion the study of “frames” and “reframing”.

In this context, the concept of “frame” was defined in two ways: on the one hand, the frame is either a map, or a territory; on the other hand, the frame was defined either as the boundary between the territory and the map, or between the maps from other maps.

In the first place, Gregory Bateson published a renowned book – "Steps to an ecology of mind" (1972) – in which, by frame, he understood a boundary (frame = boundary). His perspective had a lot to do with painting: frame is basically a boundary that is demarcating an interior space, the space of the art, to an exterior space, the space of life.

Subsequently, Erving Goffman, in another book that became famous – "Frame Analysis" (1974) – took a different approach: he considered that the frame is either the map, or the territory (so, frame = map; frame = territory). In cinema, for a picture to be in motion it needs 24 frames per second, frames that are not perceived by the audience, and are somewhat different one from another. So, the Goffman's perspective has many affinities with the cinematic vista.

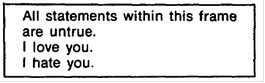

For instance, the following example was presented after the publication of the “Frame Analysis” (see Denzin & Keller, 1974 and Goffman, 1974):

This situation is interpreted differently by Bateson and Goffman. In Bateson’s vision, the frame is the border that is demarcating the three utterances that are placed inside, from the rest of the article that is placed outside. Instead, in Goffman’s vision, there is one frame that is expressed through the three utterances.

Despite this debate between Bateson and Goffman on the nature of the “frame”, subsequent generations of psychologists have not given much importance to it, giving reason either to Bateson, or to Goffman, or both alike.

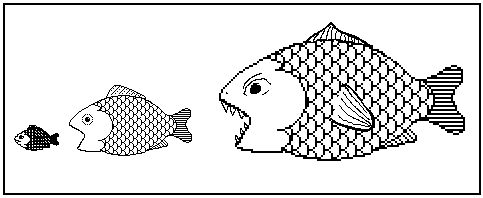

This statement is sustained by another example from the work of Robert Dilts and Judith DeLozier (2000: 1071-1072):

“As an illustration, consider for a moment the following picture.

Now consider what happens if the frame is expanded. Notice how your experience and understanding of the situation being represented is widened to include a new perspective.

Notice what happens when we reframe the situation again by widening our perspective even more.

(…) We see that it is not only the little fish that is in danger. The big fish is also about to be eaten by an even bigger fish. In his quest to survive, the big fish has become so focused on eating the little fish that it is oblivious to the fact that its own survival is threatened by the even bigger fish”

So, the next generations didn’t pay much attention to the debate between Bateson and Goffman. Richard Bandler, John Grinder, Robert Dilts, Michael Hall and Bobby Bodenhamer are some authors that are representatives for these “next generations”.

Richard Bandler and John Grinder introduced the notion of “reframing” in NeuroLinguistc Programming writing two books: “Frogs into Princess” (1979) and “Reframing” (1982). In those books, the two authors made the following assumptions:

- There is a context in which every behavior has value – this assumption being the basis for “the context reframing”

- Behind every behavior is a positive intention – this assumption being the basis for “the content reframing”

Therefore, as can be seen from the presentation of the presuppositions, Richard Bandler and John Grinder distinguished between 1) context reframing and 2) content reframing.

On the one hand, in context reframing some experience – in fact, a certain behavior – has meaning depending on the context in which it occurs: changing the space and the time of the behavior, equals with changing the meaning of the behavior.

From the perspective of the logical levels of Robert Dilts (Dilts: 1990, or Dilts: 1994) the context reframing is easier to understand as the relationship between two levels:

- The environment

- The behaviors

So, there is an example of context reframing...

“Virginia was working with a family. The father was a banker who was professionally stuffy. He must have had a degree in it. He wasn’t a bad guy; he was very well-intentioned. He took good care of his family, and he was concerned enough to go to therapy. But basically he was a stuffy guy. The wife was an extreme placater in Virginia’s terminology. For those of you who are not familiar with that, a placater is a person who will agree with anything and apologize for everything. When you say It’s a beautiful day! the placater says Yes, I’m sorry!

The daughter was an interesting combination of the parents. She thought her father was the bad person and her mother was the groovy person, so she always sided with her mother. However, she acted like her father.

The father’s repeated complaint in the session was that the mother hadn’t done a very good job of raising the daughter, because the daughter was so stubborn. At one time when he made this complaint, Virginia interrupted what was going on. She turned around and looked at the father and said You’re a man who has gotten ahead in your life. Is this true?

Yes

Was all that you have, just given to you? Did your father own the bank and just said ‘Here, you’re president of the bank’?>

No, no. I worked my way up.

So you have some tenacity, don’t you?

Yes

Well, there is a part of you that has allowed you to be able to get where you are, and to be a good banker. And sometimes you have to refuse people things that you would like to be able to give them, because you know if you did, something bad would happen later on.

Yes.

Well, there’s a part of you that’s been stubborn enough to really protect yourself in very important ways.

Well, yes. But, you know, you can’t let this kind of thing get out of control.

Now I want you to turn and look at your daughter, and to realize beyond a doubt that you’ve taught her how to be stubborn and how to stand up for herself, and that that is something priceless. This gift that you’ve given to her is something that can’t be bought, and it’s something that may save her life. Imagine how valuable that will be when your daughter goes out on a date with a man who has bad intentions.” (Bandler & Grinder, 1982: 8-9)

On the other hand, in the content reframing, one intention can be materialized in many behaviors; behaviors that can be consensual, conflicting or contradictory. So it is easy to replace one behavior by others, without the intention behind it suffers any change.

From the perspective of the logical levels of Robert Dilts (Dilts: 1990, or Dilts: 1994) the content reframing could be understood as the relationship between three levels:

- The behaviors

- The capabilities

- The beliefs

Following is an example of content reframing from the work of Bandler & Grinder (1982: 5-6):

„One day in a workshop, Leslie Cameron-Bandler was working with a woman who had a compulsive behavior – she was a clean-freak. She was a person who even dusted light bulbs! The rest of her family could function pretty well with everything the mother did except for her attempts to care for the carpet. She spent a lot of her time trying to get people not to walk on it, because they left footprints – not mud and dirt, just dents in the pile of the rug. (...)

This family, by the way, didn’t have any juvenile delinquent or overt drug addicts. There were three children, all of whom were there rooting for Leslie. The family seemed to get along fine if they were not at home. If they went out to dinner, they had no problems. If they went on vacation, there were no problem. But at home everybody referred to the mother as being a nag, because she nagged them about this, and nagged them about that. Her nagging centered mainly around the carpet.

What Leslie did with this woman is this: she said: I want you to close your eyes and see your carpet, and see that there is not a single footprint on it anywhere. It’s clean and fluffy – not a mark anywhere. This woman closed her eyes, and she was in seventh heaven, just smiling away. Then Leslie said: And realized fully that that means you are totally alone, and that the people you care for and love are nowhere around. The woman’s expression shifted radically, and she felt terrible! Then Leslie said: Now, put a few footprint there and look at those footprints and know that the people you care most about in the world are nearby. And then, of course, she felt good again.”

Almost two decades later, Robert Dilts will model the achievements of Richard Bandler and John Grinder. If Bandler and Grinder have proposed two ways of reframing, Dilts will propose, this time, fourteen ways of reframing. These new ways of reframing will be labeled “Sleight of Mouth”, an expression that has the following meaning:

“The term Sleight of Mouth is drawn from the notion of Sleight of Hand. The term sleight comes from an Old Norse word meaning crafty, cunning, artful or dexterous. Sleight of hand is a type of magic done by close-up card magicians. This form of magic is characterized by the experience, now you see it, now you don’t. A person may place an ace of spades at the top of the deck, for example, but, when the magician picks up the card, it has transformed into a queen of hearts. The verbal patterns of Sleight of Mouth have a similar sort of magical quality because they can often create dramatic shifts in perception and the assumptions upon which particular perceptions are based.” (Dilts, 1999: 6-7)

***

Much latter, Michael Hall and Bobby Bodenhamer will increase the number of reframing up to twenty patterns. They also will re-label these patterns as “Mind Lines”, another expression inspired, also, from the world of magic (Hall & Bodenhamer, 1997: 8 & 10):

“We have found a magical formula box wherein lies all kinds of wonderful and horrible things. Like a magician with his or her magical box from which to pull, and put, all kinds of wild and crazy things – the magical formula box to which we refer lives inside human brains. Even you have one inside your head! The human brain produces it, and yet the magic box transcends the brain. (…) In the pages that follow you will learn about the magic box. In it you will find your constructions of meaning. The text of this work will focus on assisting you in how to find this magic box and how to pull magical lines out of that box to conversationally reframe someone’s thinking (even your own)”

In 2007, Robert Agne wrote an article entitled “Reframing practices in moral conflict: interaction problems in the negotiation standoff at Waco.” In this article, the author presented excerpts of telephone conversations between the FBI negotiators and David Koresh during the standoff outside Waco. And Agne is trying to show that “the practice of reframing is a problematic one in crisis negotiation steeped in moral conflict”.

However, this article presents some shortcomings. First, the author utilized the notion of “frame” as is to be found in the work of Gregory Bateson, and Erving Goffman. But this notion, as defined by Agne, is explained rather in terms of the “logical levels” – a notion developed by Robert Dilts. For Agne, both spirituality and goals are two “frames”. But it is more appropriate to specify that the spirituality and the goals are two “logical levels”.

Agne made use of the work of the sociologist Max Weber to divide the frames into four types: goals – oriented, values – oriented, emotion – oriented and tradition –oriented. So, he presented the FBI negotiators as having a “goals – oriented frame”, while the Davidian branch as having a “value – oriented frame”. However, these could be more justly translated in Robert Dilts vision of life as: the FBI negotiators saw the situation at the “logical level of goals”, while the Davidian branch saw the situation at the “logical level of spirituality”

Therefore, according to Richard Bandler, John Grinder and Robert Dilts, at the logical level of “spirituality” it can be successfully used the “metaphor” technique; while at the logical level of “goals” it can be successfully used the “reframing” technique. For this reason, Robert Agne's statement that the “the practice of reframing is a problematic one in crisis negotiation steeped in moral conflict” only makes sense in his vision, presented in his article; but it does not make sense in light of the three NLP practitioners just presented.

A first conclusion arising from this article is that the universal literature is an essential element in the development of intuition. And those who have taken the due time and respected this literature, have transferred its truth in other areas such as sociology or psychology - even clinical psychology. Although its truth can neither be denied nor confirmed by real science – like mathematics, physics, or chemistry – yet this truth is as valuable as the truths these latter sciences discover, changing destinies.

Another conclusion, just as important, for this article, is that every concept has a history, and therefore has a career. A concept appears at a given date in time, being invented by someone. It may suffer some transformations, and – at the limit – it can become something totally strange to its inception. Therefore it is very important to know its nature in order not to make confusions, and make other predictions about the past.

Agne, Robert (2007): “Reframing practices in moral conflict: interaction problems in the negotiation standoff at Waco”, Discourse & Society, Vol. 18, No. 5, pp. 549-578

Andreas, Steve (1991): “Virginia Satir. The Patterns of Her Magic”, Real People Press

Bandler, Richard & John Grinder (1979): “Frogs into Princes”, Real People Press

Bandler, Richard & John Grinder (1982): “Reframing”, Real People Press

Bateson, Gregory (1972): “Steps to an Ecology of Mind”, University of Chicago Press

Battino, Rubin (2002): “Metaphoria”, Crown House Publishing

Denzin, Norman & Charles Keller (1981): “Frame Analysis Reconsidered”, Contemporary Sociology, Vol.10, No. 1, pp. 52-60

de Saint-Exupéry, Antoine (1943): “The Little Prince”, Harcourt, Brace & World

Dilts, Robert (1990): “Changing Belief Systems with NLP”, Meta Publications

Dilts, Robert (1994): “Strategies of Genius”, Vol. I, Meta Publications,

Dilts, Robert (1999): “Sleight of Mouth”, Meta Publications

Dilts, Robert & Judith DeLozier (2000): “Encyclopedia of Systemic Neuro-Linguistic Programming and NLP New Coding”, NLP University Press

Goffman, Erving (1974): “Frame Analysis”, Harper and Raw

Goffman, Erving (1981): “A Reply to Denzin and Keller”, Contemporary Sociology, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 60-68

Hall, Michael & Bobby Bodenhamer (1997): “Mind-Lines. Magical Lines To Transform Minds”, E.T.Publications

Karam, Richard (2009): “Shaping Our Perceptions of Reality Through Personal Linguistic Reframing”, ProQuest LLC, Arizona State University

Lewis, Carroll (1865): “Alice in Wonderland”, MacMillan and Co.

Rossi, Ernest (ed.) (1980): “The Collected Papers of Milton H. Erickson”, Vol. IV, Irvington

Satir, Virginia; John Banmen; Jane Gerber & Maria Gomori (1991): “The Satir Model”, Science and Behavior Books

Twain, Mark (1876): “The adventures of Tom Sawyer”, The American Publishing Company

Watzlawick, Paul; Janet Helmick Beavin & Don Jackson (1967): “Pragmatics of Human Communication”, W.W. Norton & Company

Watzlawick, Paul; John Weakland & Richard Fisch (1974): “Change. Principles of Problem Formation and Problem Resolution”, W.W. Norton & Company

Please check the NLP & Coaching for Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|