NLP and the Changing Process

Gabriel Suciu, Romania

Gabriel R. SUCIU is a sociologist. He is interested in NLP and creativity. He has written two books – “Erving Goffman and the Organizing Theories” (2010) and “Introduction to Neuro-Linguistic Programming” (2015) – and some articles, like: “Multiple Intelligences” (2011).

E-mail: gabriel_remus_suciu@yahoo.com, gabriel.suciu@ymail.com

Menu

Introduction

Robert Dilts

Mythology, art and science

Virginia Satir, Fritz Perls and Milton Erickson

Conclusion

References

There are two conflicting views on citing the sources from which an author was inspired. On the one hand it is recommended that all sources be cited so the article, the book or the material in general, no matter how original may it be, could be broken down and studied in its smallest parts. Unfortunately this is not possible because the unconscious mill grinds many things that the conscious is not aware of. On the other hand, it is recommended to offer only some citations of the sources in order to activate the reader’s creativity: a work is created by an author and, after that, recreated by the public, over and over again, ad infinitum. Unfortunately even this is not possible, because consciousness has such a need of limits and boundaries for its flocks of ideas and acts.

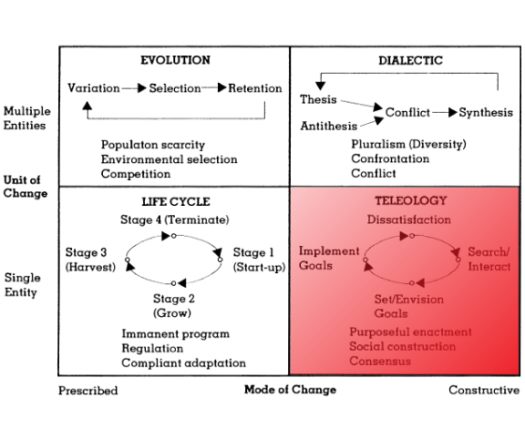

The NLP vision of change is characterized by this debate. According to the most advanced classification on change paradigms (Van de Ven & Poole [1995], Poole & Van de Ven [2004], Van de Ven & Sun [2011]) the NLP vision of change could be located in the “teleology” engine.

Although the change paradigms (“engines”) are well documented, there are few sources and references that are pointing to the NLP temporal vision of change. That being said, in this article I will present the Robert Dilts’ temporal change perspective that fits easily into the teleological change.

Yet Robert Dilts developed two visions of change - one spatial and one temporal. Strangely, the spatial vision which is well documented (unlike the temporal vision which has not been written about) can’t fit in the change paradigms proposed by Van de Ven and Poole.

Below I present the four paradigms, or “engines”, proposed by Van de Ven and Poole, emphasizing with a red square the NLP temporal vision of change.

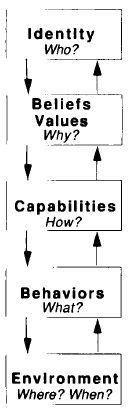

Robert Dilts presents two different perspectives of change: the vision number I - composed of 5 (6?) levels – that is a spatial vision. And the vision number II – comprising 8 stages or phases – that is a temporal vision.

1. Vision no. I

The neurological levels, this spatial vision, are imagined in two different ways by Robert Dilts, their discoverer: either as a totem, or as a pyramid.

a. The totem

“From the psychological point of view, there seem to be five levels that you work with most often. (1) The basic level is your environment, your external constraints. (2) You operate on that environment through your behavior. (3) Your behavior is guided by your mental maps and your strategies, which define your capabilities: (4) These capabilities are organized by belief systems—which are the subject of this work—and (5) beliefs are organized by identity.” (Dilts, 1990: 1, emphasis in original)

b. The pyramid

“In modeling an individual there are a number of different aspects, or levels, of the various systems and sub-systems in which that person operated that we may explore. We can look at the historical and geographical environment in which the individual lived – i.e., when and where the person operated. We can examine the individual’s specific behaviors and actions – i.e., what the person did in that environment. We may also look at the intellectual and cognitive strategies and capabilities by which the individual selected and guided his or her actions in the environment – i.e., how the person generated these behaviors in that context. We could further explore the beliefs and values that motivated and shaped the thinking strategies and capabilities that the individual developed to accomplish his or her behavioral goals in the environment – i.e., why the person did things the way he or she did them in those time and places. We could look more deeply to investigate the individual’s perception of the self or identity he or she was manifesting through that set of beliefs, capabilities and actions in that environment – i.e. who behind the why, how, what, where and when. We might also want to examine the way in which that identity manifested itself in relationship to the individual’s family, colleagues, contemporaries, Western Society and Culture, the planet, God – i.e., who the person was in relation to who else. In other words, how did the behaviors, abilities, beliefs, values and identity of the individual influence and interact with larger systems of which he or she was a part in a personal, social and ultimately spiritual way?” (Dilts, 1994: xxvi-xxvii, emphasis in original)

2. Vision no. II

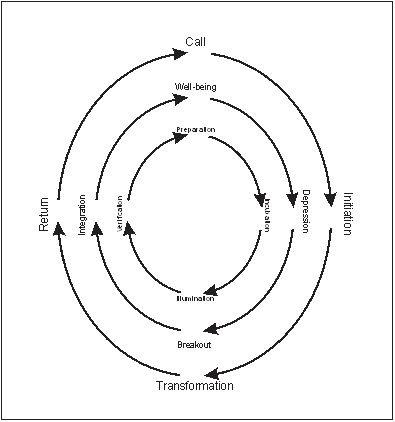

Vision number II – labeled by Dilts “a journey” – has 8 steps, or stages, arranged on a temporal axis:

- The calling. Often the call to action comes from a challenge, a crisis, a vision, or somebody in need. (…) But equally the call may come from inspiration and joy. (…) The call to the hero’s journey can come from both great suffering and great joy, sometimes both at the same time.

- The refusal of the call. And while some of the negative responses to the call may come from within, some come from outside – from family, friends, critics… or society.

- Crossing the threshold. The word has several meanings. One is the implication that beyond the threshold is a new frontier, a new territory, the unknown, the uncertain, the unpredictable, the shadowy Promised Land. Another meaning of threshold is that you have reached the outer limits of your comfort zone. (…) The third implication of a threshold is that it is a point of no return. (…) So your threshold is the point at which you’re going to go into a new and challenging territory that you’ve never been in before, and there’s no turning back

- Finding guardians. They can be actual people – friends, mentors, family members. They may also be historical figures or mythological entities

- Facing your demons and shadows. Demons are the entities that try to block your journey, at times even threatening your very existence and the existence of those with whom you are connected. (…) Shadows [are] the responses, feelings, or parts of ourselves that we don’t know how to be with.

- Developing an inner self. [The inner self is] an intuitive intelligence that connects the conscious mind with a larger consciousness that allows greater confidence, deeper understanding, more subtle awareness, and increased capacity at many levels

- The transformation. This is the time of great struggle, dedication, and battle that leads to the creation of new learnings and resources

- The return home. This return has several important purposes with respect to the journey. One of them is to share what you’ve learned on your journey with others (…) In addition to giving, the hero must receive the recognition of others to complete the journey: [the honoring of the journey]” (Gilligan & Dilts, 2009: 12-24)

The forerunners of Vision no. I (i.e. Gregory Bateson and Bertrand Russell) have been widely presented by Dilts (Dilts & Delozier, 2000; Dilts, 2007) and many others (for example: Tosey, 2006; Tosey & Mathison, 2008, 2009 or Visser, 2003). Instead almost nothing is known about the predecessors of Vision no. II. This is the reason I will show in the next pages the parallel between the change vision no. II and three fields - mythology, science and art; then I will stop only to the scientific field to show the similarity between Virginia Satir, Fritz Perls and Milton Erickson visions of change with that of Stephen Gilligan and Robert Dilts.

Stephen Gilligan and Robert Dilts were certainly influenced by Joseph Campbell:

“To begin to develop a general framework for this journey, we start with the work of Joseph Campbell. Campbell was the American mythologist who for many years studied all the different stories, legends, and myths, involving both women and men, from different cultures throughout history. Campbell noticed that across all of those stories and examples there was a certain that he called the . His first book was entitled Hero with a Thousand Faces, to emphasize that there are many different ways that this hero’s journey can be expressed, buy they all share a common framework. The following steps represent a simple version of the roadmap offered by Campbell, and is the one we will use to help us navigate the course of our own hero’s journeys during this program” (Gilligan & Dilts, 2009: 11-12)

So I will mirror the Joseph Campbell vision of change (representing the mythological field) with two other visions: that of Graham Wallas (representing the artistic field) and that of Ernest Rossi (representing the scientific field). The mirroring of those three fields – mythology, art and science – was outlined before by Ernest Rossi, and, before his writings, some writings of Carl Gustav Jung hinted to it (Rossi, 1968; 1997; 2000).

So, here they are the three visions…

1. Mythology – Joseph Campbell

According to Joseph Campbell the four stages of a myth are: the call, the initiation, the transformation and the return. The initiation and the return are two stages marked by the threshold of adventure that divides the hero’s journey into the world of living and the world of death, the surface world and the underworld world, etc.

“The mythological hero, setting forth from his common-day hut or castle, is lured, carried away, or else voluntarily proceeds, to the threshold of adventure. There he encounters a shadow presence that guards the passage. The hero may defeat or conciliate this power and go alive into the kingdom of the dark (brother-battle, dragon-battle; offering, charm), or be slain by the opponent and descend in death (dismemberment, crucifixion). Beyond the threshold, then, the hero journeys through a world of unfamiliar yet strangely intimate forces, some of which severely threaten him (tests), some o which give magical aid (helpers). When he arrives at the nadir of the mythological round, he undergoes a supreme ordeal and gains his reward. The triumph may be represented as the hero’s sexual union with the goddess-mother of the world (sacred marriage), his recognition by the father-creator (father atonement), his own divinization (apotheosis), or again – if the powers have remained unfriendly to him – his theft of the boon he came to gain (bride-theft, fire-theft); intrinsically it is an expansion of consciousness and therewith of being (illumination, transfiguration, freedom). The final work is that of the return. If the powers have blessed the hero, he now sets forth under their protection (emissary); if not, he flees and is pursued (transformation flight, obstacle flight). At the return threshold the transcendental powers must remain behind; the hero re-emerges from the kingdom of dread (return, resurrection). The boon that he brings restores the world (elixir).” (Campbell, 2004: 227-228)

2. Art – Graham Wallas

For Graham Wallas the creation process is marked by four stages: preparation, incubation, illumination (three stages taken from Helmholtz) and verification (a stage inspired by the work of Poincare):

“Helmholtz (…) gives us three stages in the formation of a new thought. The first in time I shall call Preparation, the stage during which the problem was ; the second is the stage during which he was not consciously thinking about the problem, which I shall call Incubation; the third, consisting of the appearance of the < happy idea> together with the psychological events which immediately preceded and accompanied that appearance, I shall call Illumination. And I shall add a fourth stage, of Verification, which Helmholtz does not here mention [but] Henri Poincare [does] (…) in which both the validity of the idea was tested, and the idea itself was reduced to exact form” (Rothenberg & Hausman,1996:70)

3. Science – Ernest Rossi

Ernest Rossi is the finder of four stages in science, or more specifically in psychotherapy: well-being, depression, breakout and integration. And he makes a parallel between these stages with those of Joseph Campbell and Graham Wallas.

“I originally described the four-stage creative process in psychotherapy as the breakout heuristic (Rossi, 1968). Here we find that our mood changes from a sense of well-being to depression when a Weltschmerz is experienced; the world and its usual meaning seem to crash as our familiar everyday life falls apart. We must separate from our old worldviews when they are no longer appropriate to life’s changing circumstances. In terms of the new dynamics of self-organization these critical points of choice and transition are called bifurcations. We find ourselves in conflict until we can break out of the old world to experience new awareness about our life possibilities and ourselves. We now enter a difficult period of trying to integrate the new into a meaningful life that we can actualize and bring into reality. If successful, our mood becomes one of well-being once again. In time, this new sense of well-being will again gradually mellow into mere contentment and, finally, restlessness, as circumstances continue to change. Then another creative cycle will need to take place. Each time we go through the creative cycle, we experience new levels of consciousness, identity, and spiritual maturity.” (Rossi, 2000:3-4,)

The three Neuro Linguistic Programming (NLP) famous precursors - Virginia Satir, Fritz Perls and Milton Erickson - have a vision of change similar to the vision of Stephen Gilligan and Robert Dilts: the change takes place on a time axis with past, present and future; on this temporal axis the hero go trough several steps or stages; and these stages are cyclical. The only differences between the NLP predecessor’s vision of change and the change vision no. II are the number of steps to be taken: for Stephen Gilligan and Robert Dilts there are 8 stages; while for Virginia Satir – 6 stages; Fritz Perls – 4 stages; and Milton Erickson – 6 stages.

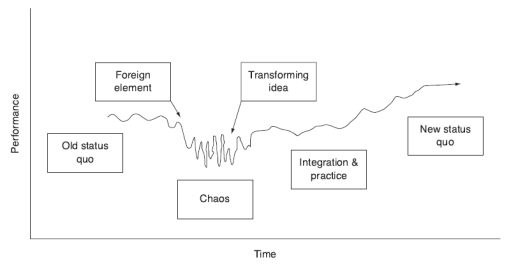

1. Virginia Satir

Virginia Satir features six stages of change: at first concise, then detailed. Grosso modo, in the Satir's vision, in the beginning there is a status quo, a situation of stability. Then there comes the chaos – or a period of major changes. And in the end the process go to a new status quo: so a new situation of stability. And this road from stability through change to stability is achieved in six stages.

Satir doesn’t make any diagram with the six psychotherapeutic steps, but her commentators and interpreters did (for instance: Cameron & Green, 2009: 36, or Karten, 2009: 44).

“(…) people who want to change go through a certain series of steps. According to Satir, this process has six stages:

- Status quo: Within the person’s or system’s existing state, the need for change emerges.

- Introduction of a foreign element: The system or individual articulates the need for change to another person – friend, therapist, or someone else outside the system

- Chaos: The system or individual begins moving from a status quo into a state of disequilibrium.

- Integration: New learning are integrated, and a new state of being evolves.

- Practice: The new state is strengthened by practicing the new learnings.

- New status quo: The new status quo represents a more functional state of being.” (Satir, Banmen, Gerber & Gomori, 1991: 98-99)

2. Frederick Perls

Frederick Perls, along with two other collaborators – Paul Goodman and Ralph Hefferline – describes a pattern of change in four stages (in particular, see chapters XII and XIII of their 1994 work): pre-contact, contact, final contact and postcontact. But the four stages are presented in a hermetic style that keeps its strength even in their commentators’ books.

For example, the following quote is taken from the book published by Woldt & Tolman (2005). A hungry person is taken as example to illustrate the four stages. At first, in the pre-contact stage, the hunger manifests itself like a need own by a body: the need is – using Perls’ own terminology – figure. In the following two stages, the objects’ need become figure: these objects belong to the environment. Finally, in the postcontact stage, the need that was background becomes again figure: in this last stage, the body becomes the center of attention.

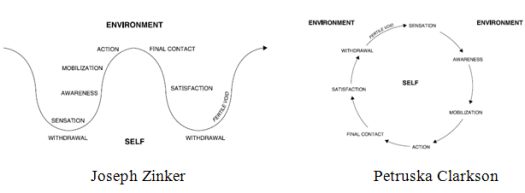

It’s worth mentioning that, until now, the four stages were not presented like a representation. However, some authors – starting from the four stages – developed other diagrams such as: the Awareness-Excitement-Contact Cycle (Zinker) or the Gestalt Formation and Destruction Cycle (Clacrkson) – see for example, Mann (2010).

“As an example of the development of the self, let us take the need of hunger. In fore-contact (…) the excitation (need of hunger) is the figure. In the following phase, that of contact (…) the desired object now becomes the figure, while the initial need or desire recedes to the background. (…) In the third phase, final contact, the final objective, the contact, is the figure, while the environment and the body are the background. (…) In the last phase, postcontact, the self diminishes to allow the organism the possibility of digesting the acquired novelty so as to integrate it, without awareness, into the preexisting structure” (Woldt & Toman, eds, 2005: 31-32)

3. Milton Erickson

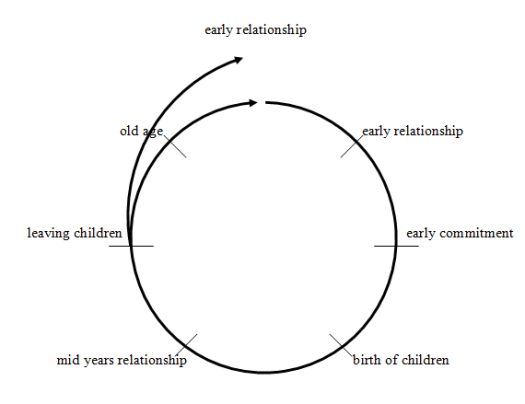

Milton Erickson doesn’t present in any of his books any stage of change. Instead, Jay Halley presents some critical stages in the family life cycle and how Milton Erickson solved the problems differently depending on these stages. So, these stages are not pertaining to specific individuals – such being the case in Virginia Satir’s work, or the work of Fritz Perls – but are stages of a group (of the nuclear family with a father, a mother and children; a family to be found in the American society): early relationship (the courtship), early commitment (the marriage), birth of children (the childbirth), mid years relationship (the dilemmas), leaving children (the dislodging), and old age.

Jay Halley doesn’t offer a graphical representation of these family life stages, but I will realize one tentatively.

“A brief outline of some of the crisis stages in middle-class American families will perhaps provide a background for understanding Erickson’s strategic approach (…) It is a rudimentary framework for the later chapters, which present Erickson’s ways of resolving problems at different stages of family life.” (Haley, 1973:29)

“The systematic study of the human family is quite recent and has coincided with the study of the social systems of other animals. Since the 1950s, human beings as well as the beasts of the field and the birds of the air have been observed in their natural environments. Both similarities and crucial differences between man and other animals, which help us to clarify the nature of human dilemmas, are becoming evident. Men have in common with other creatures the developmental process of courtship, mating, nest building, child rearing and the dislodging of offspring into a life of their own, but because of the more complex social organization of human beings, the problems that arise during the family life cycle are unique to the species” (Haley, 1973:30)

Everything in NLP is about change. More than that, everything in psychology is about change. Finally, everything in science is about change… At least, implicitly! However, for me, at least, it’s impossible to talk about everything… but not for a thing, or some thing. And this is the reason I presented just a little fragment – entitled “the temporal vision of change in the work of Dilts and Gilligan” – from this pervasive theory of change.

Below some conclusions can be drawn from this little fragment:

- No matter how exhaustive their classification of change motors want Van de Ven and Pool to be, the change vision no. I, presented by Dilts, indicates that this classification is incomplete.

- The vision of change no. II can be completed with at least three other visions, as testified by the other engines presented by Van de Ven and Poole: life cycle, evolution, dialectic.

- If the Gilligan and Dilts’ change vision is read from the glasses of Van de Ven, Poole, Ernest Rossi and many other contemporaries, a lot of its sources of influences could be specified. However, if this vision is not seen through those glasses, almost nothing could be said about its sources, since Gilligan and Dilts mentioned only Campbell as their predecessor.

Cameron, Esther & Mike Green (2009): “Making Sense of Change Management. A Complete Guide To The Models, Tools & Techniques of Organizational Change”, Kogan Page

Campbell, Joseph (2004): “The Hero with A Thousand Faces”, Princeton University Press

Dilts, Robert (1990): “Changing Belief Systems with NLP”, Meta Publications

Dilts, Robert (1994): “Strategies of Genius”, volume I, Meta Publications

Dilts, Robert & Judith DeLozier (2000): “Encyclopedia of Systemic NLP and NLP New Coding”, http://nlpuniversitypress.com, accessed February 2, 2016

Dilts, Robert (2014): “A Brief History of Logical Levels”, http://www.nlpu.com/Articles/LevelsSummary.htm, accessed February 2, 2016

Haley, Jay (1973): “Uncommon Therapy. The Psychiatric Techniques of Milton H. Erickson, M.D.”, W.W. Norton & Company, INC.

Gilligan, Stephen & Robert Dilts (2009): “The Hero’s Journey. A voyage of self-discovery”, Crown House Publishing Limited

Karten, Naomi (2009): “Changing How You Manage and Communicate Change. Focusing on the human side of change”, IT Governance Publishing

Mann, Dave (2010): “Gestalt Therapy. 100 Key Points and Techniques”, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group

Perls, Frederick; Ralph Hefferline & Paul Goodman (1994): “Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and Growth in the Human Personality”, The Gestalt Journal Press, INC

Poole, Marshall Scott & Andrew Van de Ven (2004): “Handbook of Organizational Change and Innovation”, Oxford University Press

Rossi, Ernest (1968): “The Breakout Heuristic: A Phenomenology of Growth Therapy With College Students”, The Journal of Humanistic Psychology, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 16-28

Rossi, Ernest (1997): “The Symptom Path to Enlightenment: The Psychobiology of Jung’s constructive method”, Psychological Perspectives, Vol. 36, No. 1, pp. 68-84

Rossi, Ernest (2000): “Dreams, Consciousness, Spirit. The Quantum Experience of Self-Reflection and Co-Creation”, Zeig, Tucker & Theisen, INC.

Rothenberg, Albert & Carl R. Hausman (eds) (1996): “The Creativity Question”, Duke University Press

Satir, Virginia; John Banmen; Jane Gerber & Maria Gomori (1991): “The Satir Model. Family Therapy and Beyond”, Science and Behavior Books, INC.

Tosey, Paul & Jane Mathison (2008): “Do Organizations Learn? Some Implications for HRD of Bateson’s Levels of Learning”, Human Resource Development Review, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 13-31

Tosey, Paul & Jane Mathison (2009): “Neuro-Linguistic Programming. A Critical Appreciation for Managers and Developers”, Palgrave MacMillan

Van de Ven, Andrew & Marshall Scott Poole (1995): “Explaining Development and Change in Organizations”, The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 510-540

Van de Ven, Andrew & Kangyong Sun (2011): “Breakdowns in Implementing Models of Organization Change”, Academy of Management Perspectives, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 58-74

Visser, Max (2003): “Gregory Bateson on Deutero-Learning and Double Bind: A Brief Conceptual History”, Journal of History of the Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 39, No. 3, pp. 269-278

Woldt, Ansel & Sarah Toman (eds) (2005): “Gestalt Therapy. History, Theory, and Practice”, Sage Publications

Please check the NLP & Coaching for Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|