Drilling Students Seriously

Caroline de Schaetzen, Belgium

Caroline de Schaetzen teaches Dutch to adults at the Institute for language studies IEPSCF in Uccle (Brussels, Belgium). She has worked for 25 years in a terminology center. She has published articles on computer-aided terminography and computer-aided language teaching. E-mail: caro.schaetzen@skynet.be

Menu

Throwing away computer drills ?

Preprogrammed buttons for movements

Typing recognition and feedback

Picture support

Single-choice questions

Multiple-choice questions

Sensitive screen spots

Linking items

Dragging items

A call to join efforts

Computer drills have been criticized a great deal because they do not appeal to communicative skills of the students and because they were inspired by behaviorist theories on language teaching. They are nonetheless unavoidable, in a way or another. First of all, written and oral grammar acquisition is about getting automatisms. Second, some adult students who can barely read and write in their own language cannot grasp abstract rule explanation when they are explained to them: this type of explanation is too abstract for them. Third, working on computer helps a lot distracted people to focus on the task at hand. Fourth, computers individualize the teaching by their adaptation to the different learning speeds. Last but not least, drills are an easy way to help students who have a bad memory or who are below the required grammatical or lexical knowledge to catch up with their colleagues without losing face, an important issue for adult students…

The exercises described below are executed in a multimedia computer laboratory at IEPSCF Uccle, in Brussels. Each student works at his desk at his or her own rhythm. The lab is equipped with a didactic net thanks to which the professor can see each computer screen and thus see the student interact with the course. He can thereby focus on questions like the following ones. Which rhythm are they working at ? When do they hesitate? Which strategies do they use for which mistakes ?

These drills were programmed by this author with an authoring system, that is to say software with didactic functions coupled with a programming language. The reasons why we programmed that series are the following. The material at hand for Dutch is scarce, on paper as well as for PC’s or Internet. The only grammar tutorial is interfaced with French, whereas the students who come to IEPSCF come from all over the world. The vocabulary used in the grammatical exercises of that package is too broad for true beginners and does not correspond with the one they are learning together with the grammar and the communicative activities. At last, the interactions with the computer are always the same, i. e. typing or choosing from two or three words or sentences displayed in a popping window box, which tends to bore students after a while.

This grammatical and vocabulary drills cover the items taught at a UF1 course, the one qualified as A1 by the norms for language teaching of the European Council.

It has been programmed with ToolBook, an authoring system initially conceived for the DOS environment but which has been, in a rather clumsy way, upgraded for the Windows one.

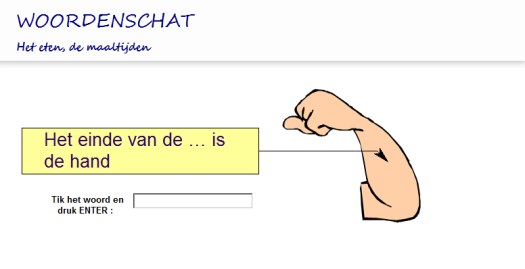

Students are prompted to name the missing part of the sentence by a text bubble stating: “The … turns left, right”, the word expected being river. Preformatted screen descriptions can be drawn by dragging items, such as the navigation buttons EXIT (getting out of the course), MENU, BACK and NEXT (sending to the previous and next screen, respectively). The type of interaction is preprogrammed too: the student is expected to type in the white rectangle; the computer is taught the admissible answers, including synonyms, if any, or spelling alternatives for one letter. The repetitive parts of the different screens, for a series of exercises, are typed once by the author, like Woordenschat, het eten, de maaltijd: vocabulary, eating, meals; Tik het woord en druk ENTER: type the word and press ENTER; Klink NEXT of druk Alt+s voor de volgende vraag: klik NEXT or press Alt+s for the next question.

The vocabulary taught is the basic one, for instance the human body parts (arm, below, with the sentence: the end of the… is the hand).

When the user types his or her answer, the computer can be made case sensitive but a dummy can also be provided, for instance in answers where both y and i are allowed.

The basic vocabulary is also taught indirectly together with the grammar, like with the present tense, below: he (to have) a parcel. We thought it is also important to give feedback after each sentence or word asked for, and not only at the end of a whole exercise. We find also important to give detailed feedbacks, and not simply an X for a mistake or a V for a correct answer. Here the feedback says the equivalent of: Sorry, this is wrong. With “he” or “she”, the verb is “has”. A different feedback can be provided according to the wrong character chain typed by the user. The user can also be sent to a particular place in a computerized course according to his or her answer.

The pictures above are clip arts which are royalty free. They come from a collection of twelve CD’s offering clip arts, drawings and photographs. These types of picture resources are only available on Internet nowadays, which makes their downloading cumbersome and time consuming… It seems important to me to use picture collections. In the series of photographs from which the car below comes from, the proportions, background and colouring of the objects are coherent, which probably gives a more professional look to the whole. Ik rijd met een (rood) auto: I drive a red car and the students is prompted to choose either rood or rode (in this case, rode is the right answer, since the noun immediately follows the adjective and is not a singular neutral one, an indication give by De auto [as stated in the dictionary entry of “car”]).

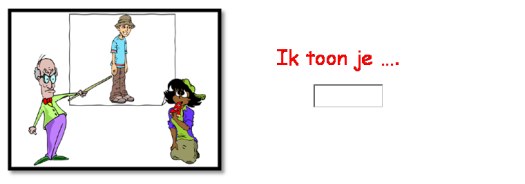

The systematic character of the cliparts can be precious for certain items to teach in a coherent manner. In the follwing screen, the pronoun as an object but also the possessive adjective can be taught with quite similar pictograms: ik toon je…: I am showing you…, the expected answer being hem (him).

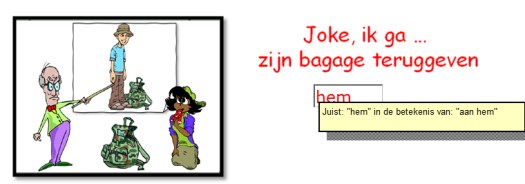

We see below the student typing hem again, but we are also seeing the possessive zijn (his): Joke, ik … zijn baggage teruggeven: Joke, I am going to give him back his luggage. The luggage is the only different feature on both screens, an indirect way of showing the link between possessives and personal pronouns.

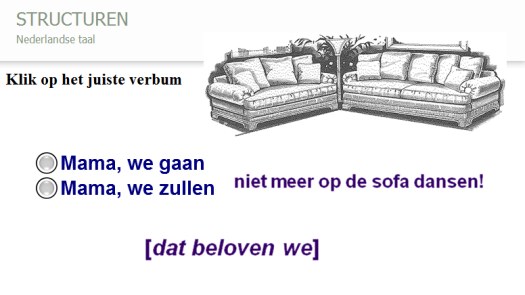

Simple alternatives are classical in computer drills. A generator of drills like hot potatoes enables to make exercises providing them to students. Of course a versatile and full-fledged authoring system like Authorware or ToolBook enables to use that type of interaction with the user too, the user clicking on the radio button of the alternative he wants to select. The screen below proposes two alternatives for niet meer op de sofa dansen: no more dancing on the sofa in the future tense, the verb gaan (used as going to for intentions) and zullen (used like shall, as a promise to do, or to refrain from doing, a particular action, the implicit promise being mentioned by [dat beloven we]: we do promise it)

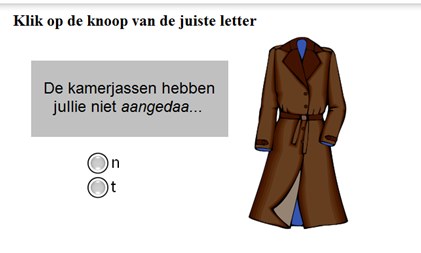

Simple alternatives are handsome for word endings, when there are only two alternatives, a regular (t/d, in Dutch) or an irregular one (-en or –n, in Dutch, together with a vowel change: doen: to do becomes gedaan: done).

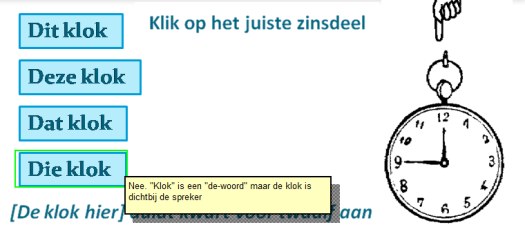

Lots of software packages for didactic purposes do not enable to conceive multiple alternatives. ToolBook provides that feature. This is important for demonstratives, in Dutch, where the number of alternatives is four, the criteria combining the proximity (the equivalent of here or there) and the gender (the equivalent of a the- or a it-word) of the substantive.

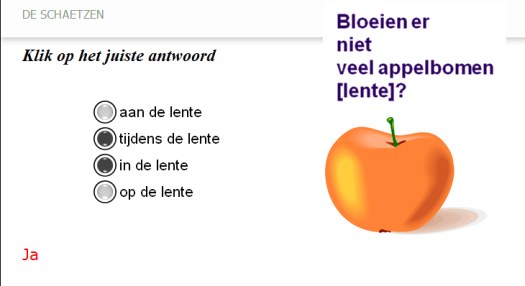

That feature is undispensable for synonyms, too, like below for during followed by a period of time, where the prepositions chosen are both correct (gedurende de lente: during the spring, in de lente: in de spring).

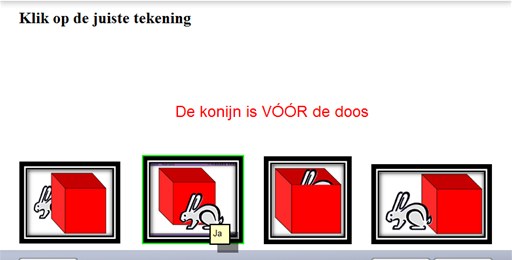

Combining multiple alternatives with sensitive screen areas can prove quite economical and, as such, elegant. Below, for the sentence De konijn is vóór de doos: the rabbit is before the box, the student has to klik op de juiste tekening: klik on the right picture (which he actually did). Again, the picture collection also shows its evocative might. Any part of the screen can be chosen by the author as a right or wrong answer.

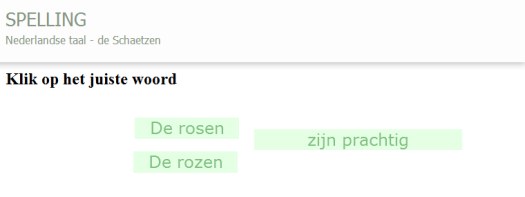

By the way, a strong recommendation by specialists is to avoid the pedagogical sin of showing mistakes to the learner. Well, that sin seems unavoidable. For one, how can alternatives been shown, like in spelling, such as below?

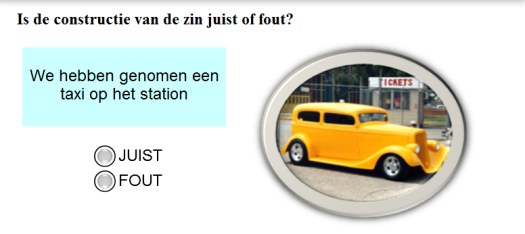

Then, the issue of word order makes the display of common mistakes a must, in a way. How on earth can prominent errors been eradicated if they are not explicitely pointed at, let us say at least once? Drawing the attention of French speakers to that matter is particularly important, since they are bound to make the mistake… Below, the sentence we hebben genomen a taxi op het station: we have a taxi at the station taken is fout: wrong and not juist: right (the participle has to be moved to the end of the clause).

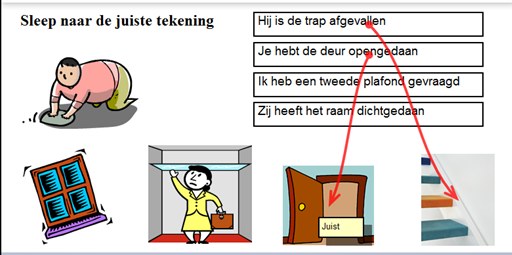

A nice feature of ToolBook, which again Hot Potatoes does not provide, is the possibility to ask learners to draw an arrow between two elements. Below, the screen gives four examples of present perfect sentences: his is de trap afgevallen: he has fallen from the stairs; Je hebt de deur opengedaan: you have opened the door; ik he been tweede plafond gevraagd: I havec asked for a second ceiling; zij heeft het raam dichtgedaan: she has shut the window. The student has to link the right object, like the stairs for the first sentence. The arrow seems drawn on the spot by the student, which gives him or her a nice sense of natural, informal, interactivity. If the student tries to make a wrong link, the red arrow will not show.

Together with the arrow, button labelling can also be very economical at times.

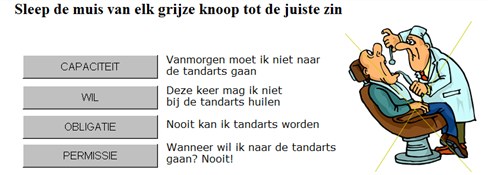

Below, thanks to the multiple-choice buttons, respectively labelled capaciteit: capacity; wil: will; obligatie: obligation; permissie: permission, the teacher can remind a grammatical rule, namely, the difference between the modal verbs kunnen: can; willen: will; moeten: must; mogen: may/might. The student has to link the meaning of each modal to the sentence using that particular verb. Capaciteit with nooit kan ik tandards worden: I can never become a dentist); wil with wanneer wil ik tandarts worden? Nooit: when do I want to become a dentist? Never; obligatie with vanmorgen moet ik naar de tandarts gaan: this morning I have to go to the dentist; permissive with deze keer mag ik niet bij de tandards huilen: this time I may not cry at the dentist’s.

Note that the author can draw anywhere on the screen, like the crossing of the clipart, on both screens below, by which the negation in the sentences is alluded to.

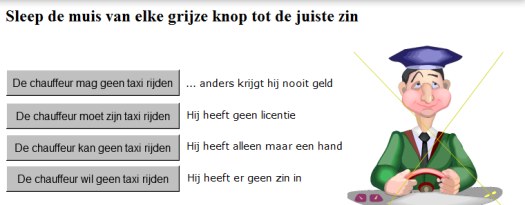

The buttons can change functions inside a series of activities, so that the coherence of the whole is preserved. After a few examples like the one above, the four modals come into play as button labels, the student having to link each sentence with a modal to the right context. De chauffeur mag geen taxi rijden: de driver may drive no taxi with hij heeft geen licentie: he has got no licence; de chauffeur moet zijn taxi rijden: the driver must drive his taxi with anders krijgt hij nooit geld: otherwise he will not get any money; de chauffeur kan geen taxi rijden: de driver cannot drive a taxi with hij heeft alleen maar een hand: he has only one hand; de chauffeur wil geen taxi rijden: de driver does not want to drive a taxi with hij heeft er geen zin in: he does not want to.

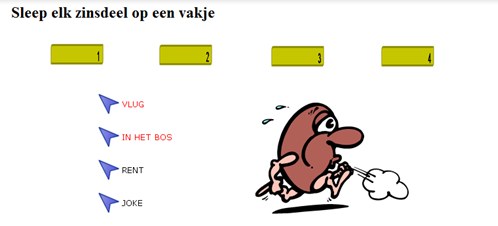

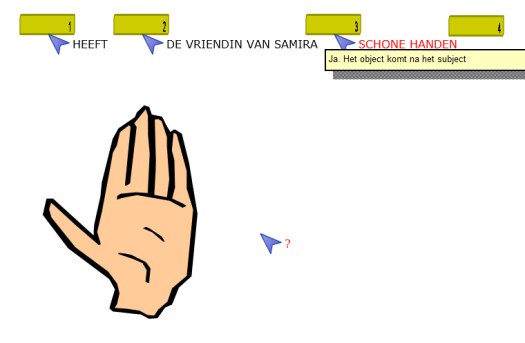

The dragging of screen objects asked for by sleep elk zinsdeel op een vakje: drag each sentence part to a block is a very powerful feature of ToolBook indeed. It is especially useful to show word order, a difficult feature in questions, inversions, two-verb sentences, subordinates. Below, the parts of the affirmative sentence Joke rent vlug in het bos: Jos runs quickly in the wood have to come into place, Joke under constituent block number 1, rent under number 2, etc.

If the students tries to drag an element to a wrong place, it comes back where it comes from. When it is at the right place, a positive feedback is displayed, such as the one below. Ja. Het object komt na het subject: yes. The object comes after the subject.

Allow me another methodological remark at that point. As the Pilgrim’s seminars such that of Simon, Hania and Paul showed, the use of the right metagrammatical vocabulary, possibly without too much insisting, is not felt as heretical any longer, in adult language teaching. The use is particularly important especially for Dutch teaching in Belgium, where half of the students have been exposed during years to language courses where the accent lied heavily on grammatical and lexical theories. To build bridges with the everyday life of learners also implies mind mapping with linguistic theories he or she has learnt together with the language proper.

As the examples above hopefully showed to the reader, a minimal variety of interactions with the computer has become a must in the modern computer-aided language teaching for the simple reason that it is user-friendly.

Languages with a limited use like Dutch are also prone to require a higher degree of implication from the teachers. They are used to prepare their course much longer than their English language, French and German teachers. As shown in the present article, this can imply the use of a decent authoring system, to compensate for the lack of good drill package.

In those matters, solidarity should be the rule and not the exception. It is about time the computer didactic material at hand circulates in all the countries involved in the use of those languages. For Dutch, it means the Netherlands but also Belgium, France, South-Africa, Indonesia and Curaçao.

Below one language, exercises like the ones above could be conceived with a multilingual target at the outset, with the text (for instance, that of the feedback) being stored in an easily accessible database.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the ICT - Using Technology in the Classroom – Level 1 course at Pilgrims website.

|