Do Consciousness Raising Activities Improve Learning?

Nick Morley, Malaysia

Nick Morley has recently taught for the Center for Educational Policy at Nazarbayev University, Astana, Kazakhstan, and he is currently a Training Fellow for Brighton Education at the Institute Pendidikan Guru Campus in Kuching, Sarawak. Malaysia. He holds an MA TESOL and an M Ed (Applied Linguistics). His professional interests lie in pursuing a Doctorate in Education by investigating creative and critical thinking. He has an interest in helping learners notice language they use and discover how to improve it themselves and enjoys working with lower-level teenage learners, who need learning support.

E-mail: xyiq@yahoo.com Skype: nick.morley111

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

What are CR tasks are and how do they work?

Range of use

Less emphasis on accuracy

Naturally learner centered

Should CR tasks be focusing on grammar?

Basic background theory

Shift in emphasis

Support for using CR tasks

Potential problems with using CR tasks

Summary

Conclusion

References

This article explores aspects of consciousness raising CR tasks and the discussion addresses the question of whether and how CR tasks improve learning. This discussion outlines beneficial aspects of CR theory in relation to practice and also highlights possible negative consequences associated with uncritical implementation.

Early stages of teacher development can be so taken up with classroom management, choosing resources and lesson planning that some aspects, such as, how learners learn languages and how to support them in learning naturally often remain unexplored in the background.

From social constructivist and cognitive perspectives, consciousness raising CR tasks are learner centered as successful outcomes rely on how learners notice and actively engage with language and then make it their own. These aspects are diametrically opposed to the transmission model, which is still predominant in many countries and widely regarded as responsible for creating a culture of dependent learners, who are overly reliant on memorization and route learning. Ponniah (ca 2007) rightly points out that language learning is in essence a thinking driven process and suggests learners are not only developing linguistic skills sets but also experiencing a period of personal growth. This aspect of person growth is possibly more noticeable with young learners as they explore and develop belief systems about the world.

Ellis (2004) refers to consciousness raising as; ‘…indirect explicit grammar instruction,’ and he suggests that advantages lie in; ‘…opportunities for learners to interact in the target language, while learning about it,’ Ellis (ibid: 160). CR tasks are not intended or designed to elicit immediate language use but rather to help learners develop internal representations of the new language. So, regardless of whether learners are working deductively or inductively their CR task will be made up of some kind of language data and an awareness raising activity to be performed on it. While working with the data on their task(s) learners are likely to notice aspects of it.

One of the positive aspects is the broad range of potential tasks that creative teachers can design. This range varies considerably, from being able to recognize a language point and how it works, to learners creating their own language activity for peers to work on. Task range and complexity, if positioned on a cline from simple to complex, incorporates relatively simple cognitive processes, such as, passively recognizing a language point, for example, underling -ing endings, through to more complex skills requiring in depth cognitive processing. Such in depth tasks might involve learners in writing a dialogue with intentional errors for other learners to correct. Therefore, CR theory has excellent potential for adaptation, making it suitable for young learners, discussed by Cameron (2001) through to adults, discussed by Thornbury (2000).

The range of potential tasks, materials and amount of cognitive effort involved varies considerably, which is part of the beauty of CR. This is an area with continually evolving potential relating to the kinds of language input available to us today, such as, the Internet (interactive texts and images), youtube.com (video clips for viewing and posting responses), IC recorders (live recordings of students or other speakers, digital images (for context or representing the target language), Microsoft Word/Power Point (enhancing items in text through boldface type and or color coding) and web based applications such as cartoon creators or blog sites.

At first CR theory appears to run contrary to the norm, as authors, such as, Ellis (2004), Lightbown and Spada (1996) and Thornbury (2000) emphasize how accuracy eventually arises out of fluency as learners ‘get it right in the end.’ Therefore, teachers need to adapt to the approach that learning is best supported by manipulating the language input instead of constantly trying to correct learners’ output. A beneficial effect with this approach is that it reduces learners’ experiences of frequent correction and insistence on accuracy, which is inhibiting and discourages them form experimenting with new language.

Sensitively applied CR activities are in tune with a social constructivist perspective, as they encourage learners to notice, experiment with and acquire language in ways closely attuned to innate abilities, rather than being dependent on external controls. For example, Cameron (2001) illustrates how young learners unpack chunks of language, noticing the components as they do so before finally recombining them as novel utterances and making them their own. This process emphasises individuals as a ‘meaning makers,’ interacting with and shaping their social worlds; as opposed to ‘blank slates’ or ‘empty vessels’ requiring an authoritative source to ensure learning takes place.

Ellis (2004) addresses this question, taking the position that communicative language classrooms predominantly encourage high levels of fluency and listening comprehension but frequently fail to produce matching levels of grammatical proficiency. This skills deficit implies a need for form-focused instruction to redress the imbalance. A potential problem here is that as Pienemann (1986), shows, learners need to be in state of (psycholinguistic) readiness before noticing and acquisition can take place. This suggestion of readiness is probably more in tune with children learning their L1 in a family setting and places unrealistic demands on teachers. This aspect is unrealistic as it would require the teacher to be exceptionally sensitive to each learner in large classes, which is not feasible in primary or secondary school settings. However, form focused instruction works well, with lasting effects as long as we implement the main principle; that items need to occur frequently in the environment to be retained, for example, by regular recycling, Lightbown (1992).

Starting with grammar teaching and a structural syllabus, Ellis (2004) argues that instead of targeting learners’ developing language systems (interlanguage), we should be providing them with information they need to notice and understand new language features. As a result, this awareness naturally causes learners’ developing language systems to change.

However, this perspective leads to a potentially contentious point; that CR tasks are not intended to elicit immediate language use, but instead, to support construction of internal representations of language. This is potentially contentious, as in the normal turn of events classroom language presentation is followed by learner production and teacher evaluation (feedback) on how well this was achieved and some form of correction and further practice. Therefore, this aspect implies that delaying evaluation and feedback are preferable strategies; however, this does not match the common beliefs about what teachers do while they teach and the role of the teacher as an evaluator who monitors and corrects learners’ output.

With CR tasks then, there is a shift in emphasis towards what learners are able to do for themselves only after they have noticed the language and importantly, noticed gaps between what they can currently do and what they need to do. So, it is learners who are taking on the role of monitoring their output.

In order to promote self -monitoring, Ellis (2004) and Thornbury (2000) highlight a common misconception, that only accuracy is a worthwhile goal, which is something teachers reinforce through sustaining a tightly controlled focus. Rather than narrowly focusing on accuracy, the authors suggest using error inducement, whereby learners are provoked into producing common developmental errors which in turn helps them notice differences between their current abilities and native speaker norms. Ellis clarifies the role of CR as separating out grammar comprehension from message comprehension, where effective, CR tasks push learners to notice gaps between how a language point is working and how they are producing it. This is where utilizing learner errors can be most effective in preventing early fossilization (where learners are able to communicate reasonably effectively but rely on incomplete or restricted language forms) in communicative or immersion settings, Lightbown and Spada (1996). CR tasks focus on what learners are doing when interpreting messages. Cook (1991:58) illustrates this by making distinctions between decoding and code-breaking: ‘…. Decoding to get the “message,” versus code –breaking or processing language to get the “rules.” Combining CR with focused communication tasks supports learning language rules by code-breaking, as learners need to be aware of the code with its accompanying patterns and regularities. Advances in teaching technologies make kinds of visual code recognition and code-breaking easily achievable, for example, using word processors and highlighter color codes to draw attention to how language is functioning. Learners’ written work in soft copy can be edited through color code highlighting, but not corrected with codes serving to draw learner’s attention to types of errors and provide clues for self or peer -correction.

Cameron (200:091) suggests CR task style and demands need to consider learners’ ages; therefore, tasks for younger learners will need careful grading. Grading task demands might necessarily be mediated by teacher talk, where the teacher scaffolds the task by: ‘…directing attention and remembering the whole task, the instructions, stages and goals on behalf of the learners.’ This type of task management and scaffolding usefully reduces the amount of attention and cognitive load placed on very young learners. By reducing the amount of attention needed to carry out task stages learners are freed up to notice how language is used.

It would seem commonsensical that attention and noticing, defined by Schmidt’s Noticing Hypothesis (1990A, 1990B) provide foundations for learning. However, many researchers state, attention and noticing may not always work in ways most helpful to learners. Carroll (1999) suggests learners may even mistakenly filter out essential information, which does not match their expectations. Laufer and Girsai (2008:05) demonstrate how this happens with items which are less frequent or non – salient (language points not easily recognised) or communicatively redundant (they are not strictly necessary for understanding) stating that these aspects,’….may go unnoticed unless attention is drawn to them.’

Gas (1988:209) further emphasizes what needs to be done for successful learning to take place: ‘…they must first recognize (Not necessarily at a conscious level) that there is something which is in need of modification—that there is a perceived mismatch between native speakers…’ Therefore, language development is not a random process and development cannot take place without selective attention.

CR tasks seem to focus on manipulating language input; however, learners’ output can also play an important role. Once learners have noticed a performance problem, they will be motivated to modify their production, Swain and Lapkin (1995:371). When learners are able to see the need to modify their language output they are likely to feel encouraged to spend more time on decoding and processing grammar in order to do so.

To sum up the learning problems that CR tasks aim to solve, Han et al’s (2008:01) research question neatly encapsulates the goal: “Why is it that L2 learners typically appear to ignore a vast mass of evidence and continue, obstinately, to operate with a system that is in contradiction with the target norms as manifest in the input?” Sharwood Smith (1991) supports learners using decoding as well as code-breaking strategies by proposing these strategies can be promoted by enhancing the quality of language input. Improving input quality can be achieved very simply; by using; underlining, colour coding, italics or bold font for visual input as well as other presentation strategies such as repetition. There is a range of options for increasing learners’ exposure to target forms, ranging from low-tech options achievable in almost any setting to the high- tech. Two techniques commonly used by materials writers for exposing learners to frequent examples of the target language are flooding and input enhancement. When flooding is used, learners are exposed to high frequency examples, often in artificially constructed texts or communication activities, such as, Have you ever… ?, questionnaires, which ensure prolonged exposure and production of the present perfect. Today, we can see elements of research into CR tasks and input enhancement filtering through to course books. Techniques stemming from Sharwood Smith’s (1991) suggestion that color coding increases prominence or noticability of the target language are now featured as well as tasks asking learners to locate, underline or highlight language points within more natural examples of texts.

A final word on CR theory, placing it firmly in the context of the learning that takes place in any human endeavor, comes from Gass’s (1988:203) discussion of language learning being little different from any other type of learning because learning takes place when, ‘….experience interacts with new input.’ Learners notice new information in light of past experience and then construct new information from it. The crucial factor is the equal importance given to dual roles learners and teachers play. While learners are developing by noticing gaps between present abilities and new language, teachers need to support them by ensuring gaps are narrow enough for noticing to take place. Emphasis on how these two roles work together marks meaningful shift away from the transmission model towards learning in partnership.

Bearing in mind that new theories or approaches should not be implemented uncritically, we now turn to pros and cons of using CR activities. The concept of CR seems ideal from a teacher’s perspective, or at the very least, it is likely to be benign. However, it soon becomes apparent that arguments for and against exist, for example, while CR tasks could result in creative classroom applications and inspire teacher training and development, there are other factors to consider, such as; classroom management (the clarity of environment required for noticing is to take place), learner motivation, and intrinsic interest inherent in the task, plus whether learners’ prior experience makes them amenable to learning in this way. Some cultures may not see the value in an indirect and less controlled approach and a certain amount of explanation and learner training might be needed.

CR tasks have been shown to work effectively but this raises the question of what to focus on and whether all language points are amenable to enhancement? Gass (1982) suggests learning can be accelerated when learners are taught more marked language first (new language with consistent form and use, such as the passive voice). Ellis (2004) supports this, suggesting learning may well be hierarchical as learners can generalize from marked to unmarked features (language with more ambiguous rules or uses) but not vice versa. Caveats raised by Lightbown (1992), suggest initial good performance following CR tasks is likely to deteriorate without frequent opportunities for practice and review. This aspect is problematic in EFL settings where learners are limited to two or three hours of language learning per week but still expected to progress through increasingly complex language syllabi.

Using graded or simplified language may be doing learners a disservice by not providing enough of the right kind of rich language input needed to build up a base of grammar knowledge, Ellis (2004). Therefore, although used with the best of intentions, simplifying input to ease comprehension reduces learners’ access to more complex structural information; so, that understanding may take place but not learning. This phenomenon is linked to fossilization, whereby learners reach a level of pragmatic competence (an ability to function socially), which does not reflect their actual language competence. Subsequently, form focused instruction helps prevent early fossilization and CR tasks focusing on learner errors could be a highly effective option for remedial instruction.

When it comes to putting CR theory into practice, Thornbury (2000) is an excellent starting point, as he puts forward a number of ideas based on pedagogically sound principles, which are adaptable to different age groups and levels. Thornbury (2000:84) supports the need for (CR) tasks to overcome early fossilization experienced by learners who acquire language in communicative settings but soon reach a performance plateau. In order to progress beyond this performance plateau, learners need to become aware of what they cannot do well by noticing the gaps in their performance. ‘It is important for the learner to notice the differences (between their performance and the target) for themselves …in order for them to make the necessary adjustments to their mental grammar. ’Lightbown and Spada (1996:102) further support the position that CR tasks are necessary for learners in communicative settings by suggesting that a more balanced approach to teaching, incorporating CR should counter documented effects of too much freedom in unfocused communicative language settings resulting in early fossilization.

When discussing how young learners move from being dependent on using words to using grammar, Cameron (2001:102) draws on cognitive psychology to emphasize how learners’ cognitive processing limitations, in terms of memory or cognitive load, restrict the amount of noticing that can take place. These limitations suggests formulaic chunks need to be learned and used before CR tasks can effectively assist learners in unpacking their meanings in order to progress towards recombining them in creative ways. The author uses Mitchell and Martin’s (1997) term: ‘…from chunks to creativity.’ This example shows theoretical advances need to be implemented sensitively when it comes to methodology and demonstrates how aspects of audio-lingualism can effectively assist learners by supporting initial rote learning of fixed phrases, which can be broken down later. Therefore, after considering this aspect, teachers might find that a more eclectic approach is needed to maximize learning opportunities.

Cameron (2001:109) emphasizes the need for noticing as a prerequisite to grammar learning, stating that without an awareness of how the target language is used, learners’ language can break down under the pressure of communicative tasks. In identifying what CR tasks need to feature before communicative activities can take place, the author suggests:

- ‘Support for meaning as well as form’

- present the form in isolation as well as in discourse context

- contrast the form with other known forms

- require active participation by the learner

- be at a level of detail appropriate to the learner

- lead into but not include activities that manipulate language’

The final item, ‘lead into but not include activities that manipulate language’ might be usefully adapted to suit individual learners or groups based on the teacher’s assessment at the time. This item is singled out for flexible application, as manipulating language at the right time could be a highly effective form of learning support.

Learners produce two kinds of errors. Developmental errors, for example; when learners attempt to transfer aspects of their first language to learning their second one. Developmental errors are regarded as natural and similar to errors children make when learning their first language. However, CR tasks can provoke overgeneralization. Overgeneralization errors, for example, occur when learners meet high frequency presentations of the present continuous and then start over using it out of context, Lightbown and Spada (1996).

CR tasks may not suit all learning styles, considering field dependence FD and field independence FI in relation to learners’ cognitive styles. Those orientated towards FI are better at distinguishing shapes or patterns in pictures; they are the people who can ‘see the monkeys in the trees.’ Therefore, FI orientated learners are at an advantage with academic tasks and might have a natural preference for CR tasks. However, CR tasks may disadvantage FD learners because task design pushes them to process language in ways at odds with preferred learning styles as they tend to be more dependent on environmental or contextual clues, Cook (1991).

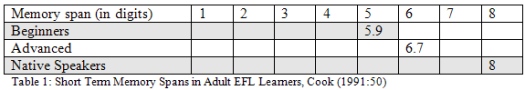

Staying within the cognitive domain, Cook provides further insights into the most appropriate intensity for CR tasks regarding learner proficiency. Considering the role of short-term memory STM in language learning and the negative effects of cognitive load (if the processing load is too high, memory performance deteriorates) serves as caution when designing or using CR tasks. Too much complexity with lower level learners may overload them so they not only fail to notice new language items but also fail to perform as well as they might have on a non CR task. Therefore, we need to be aware that two separate systems are working and possibly interacting negatively because, ‘…all teaching activities involve STM load as well as language load,’ Cook (1991:53.)

To illustrate how learners at different levels use STM on tasks and how complex task design affects performance for different levels of language users, the results in table 1 below show Beginners had less STM available for language use when compared with Advanced and Native Speaker groups. This example illustrates that as teachers, we need to consider what learning tasks actually require learners to do and be willing to adapt them accordingly.

CR tasks may not always be productive as Sharwood Smith (1994) states; the use of highlighting strategies (highlighting, colour- coding or boldfacing parts of a text) may obscure more subtle aspects of language and inadvertently hold learners back. This dichotomy is clearly evident throughout CR task design as teachers can isolate, focus and simplify parts of a message in order to help learners notice it, while simultaneously exercising high levels of control over what is attended to. As the authors mention, this narrowed focus on what is attended to may very well reduce the possibilities for incidental learning and noticing to take place.

CR tasks, as with any other task types, can potentially create negative learning experiences when learners are asked to attempt tasks beyond their capabilities. Mismatching task to ability can create self-doubts about language competencies; therefore, teachers need to design or critically select appropriately graded tasks and materials.

Another potential negative aspect of task design is requiring learners to focus on specific items, for example, paste tense -ed word endings. This controlled focus might cause learners to be more self-conscious and inhibited in their language production, which interferes with subconscious language knowledge, Sharwood Smith (1994).

To address the question, ‘How much noticing is possible?’ Learners might be predisposed towards avoiding noticing different aspects of the same form. ‘Would,’ for example, can be used to make offers as well as discuss likelihoods, and this use can easily be contrasted through task and materials design. However, this idea is not quite so clear- cut as the phenomenon of avoidance of ambiguity indicates that language learners are naturally pre-disposed towards noticing uniqueness. Therefore, tasks requiring attention to different uses of the same form would create the sense of ambiguity, which learners naturally try to avoid, Sharwood Smith (1994).

Initially, it appears that teachers are only required to highlight aspects of comprehensible language input in order to ease the learning process. However, the learning process would seem to be far more complex than this, because learners also need a certain amount of incomprehensible language input to make them aware of areas they do not understand, which then stimulates learning and supports long- term development, White (1990).

CR tasks support teaching and learning needs, especially with groups amenable to less teacher- led approaches. The CR tasks are relevant to lower level learners, who may have experienced failures with more teacher- led grammar presentations, and who may also need plenty of varied recycling and review in order to sustain their interest. Varied recycling and review is where combinations of CR tasks would be beneficial. Han et al (2008:18) suggest the following approach:

- Combining forms of enhancement is likely to promote greater depth of processing and encourage positive ‘overlearning’.

- Acquisition will only be speeded up if learners have previous knowledge of the target language.

- Learners are likely to notice meaningful forms automatically.

- When meaningful forms are enhanced simply, this contributes to comprehension.

The first item, ‘Combining or compounding forms of enhancement being likely to promote greater depth of processing and encourage positive ‘overlearning’ is interesting for teachers designing or understanding learning tasks. This approach is readily achievable, for example, moving from simple to more progressively more complex demands for a language point, such as, ‘used to’ could involve the following stages:

- Show learners pictures of an adult and child with the accompanying strips of text: go to school, goes to work, be afraid of the dark, rides a motorbike, get pocket money, travels abroad etc. The aim for this stage is for learners to match texts to the most likely picture.

- Ask learners when the activities took place, in the past or now and whether or not they occurred often. Learners order their text slips under the headings ‘past’ and ‘now.’

- Learners list the activities under two headings ‘Used to… (in the past)’ and ‘Now.’

- Learners then make similar lists about themselves and then in pairs take turns to decide whether the partner’s activities are true for the past or present.

- Use the results from learners’ lists about themselves to model a report about a volunteer, for example, Ploy used to live in Chaing Mai, She used to like pizza, she used to have a cat, she lives in Bangkok, she learns English on Saturdays.

- On the board, show a half completed rule for ‘Used to,’ such as:

‘We use “used to…” to talk about…

- Things still true now

- Things that happened once or twice in the past

- Things that happened regularly in the past

- Things that happen regularly now

Learners choose the correct version and write their own summary for talking about frequent past and present events.

- Learners then go on to work in 3s and tell the new partner about each other by using ‘used to…’

There are various opportunities for moving towards consolidation stages, one option would be to work online with a class blog for learners to write about each other or look up the biography of someone they are interested in. Each time they type ‘used to’ learners would use a different coloured font to highlight the item. Completed blogs could then form the basis of a class quiz in the next lesson, for example, with true or false items such as ‘Ploy used to live in Chaing Mai,’

CR theory and tasks have a lot to offer; however, a balanced view of how they work and potential problems shows they should not be implemented uncritically. For, as mentioned earlier, how effectively CR tasks support learning depends on many factors such as; learner proficiency and task difficulty, clarity of presentation, how clear and unambiguous new language is, if the task style compliments or conflicts with preferred learning styles or whether task design, such as, input flooding where learners are introduced to artificially high frequencies of the language then causes them to over-generalize or overuse it. Finally, even if the CR tasks are working effectively, learners still need plenty of opportunities to recycle and review new language.

Cameron, L. (2001). Teaching Languages to Young Learners, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Carroll, S. (1999). Putting ‘Input’ in its Proper Place, Second Language Research, Vol.15; 337 -388.

Cook, V. (1991). Second Language Learning and Language Teaching, New York, Routledge.

Ellis, R. (2004). SLA Research and Language Teaching, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Gass, S.M. (1998). Integrating Research Areas: A Framework for

Second Language Studies. Applied Linguistics, Vol 9, No. 2, 199 -217.

Han, Z.H., Park, E.S., & Combs, C. (2008). Textual enhancement of input: Issues and possibilities. Applied Linguistics, Vol.29 No.4, 597-618.

Laufer, B. And Girsai, N. (2008). Form-focused Instruction in Second Language Vocabulary Learning: A Case for Contrastive Analysis and Translation. Applied Linguistics, Vol.29 No.4. 694-716.

Lightbown, P. (1992). Can They do it Themselves? A Comprehension Based ESL Course for Young Children, in Ellis (2004). SLA Research and Language Teaching, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Lightbown, P. and Spada, N.(1996). How Languages are Learned, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Mitchell, R and Martin, C.(1997).Rote Learning, Creativity and “Understanding” in Classroom foreign Language Teaching. Language Teaching Research, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1- 27.

Psychological Constraints on the Teachability of Language. In Pfaff,C,W. (Ed), First and Second Language Acquisition Processes. Rowley MA, Newbury House.

Ponniah, R.J. (ca. 2007). Memorization a constraint for integrating thinking skills into Indian ESL classrooms. Available at : wwww.languageinindia.com. Accessed 2 June 2011.

Schmidt, R.W. (1990a). Consciousness, Learning and Interlanguage Pragmatics. University of Hawai’i Working Papers in ESL Vol. 9, 213–43. In Carroll.S.(1999). Putting ‘Input’ in its Proper Place, Second Language Research, Vol.15; 337 -388.

Schmidt, R.W. (1990b). The Role of Consciousness in Second Language Learning, Applied Linguistics. Vol.11, 127–58.

Sharwood Smith, M. (1991).Second Language Learning: Theoretical Foundations. Harlow, Longman.

Swain, M.and Lapkin,S.(1995). Problems in Output and the Cognitive Processes They Generate: A Step Towards Second Language Learning. Applied Linguistics. Vol.16, No.3, 372 -391.

Thornbury, S. (2000).How to Teach Grammar Harlow, Longman.

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Building Positive Group Dynamics course at Pilgrims website.

|