Adolescents’ Beliefs About Group Activities and Peer Collaboration while Learning EFL Through Music in Brazil: A Sociocultural Analysis

Fernando Silvério de LIMA, Brazil

Fernando Silvério de Lima (M.Sc., Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Brazil) has taught EFL mainly for adults and adolescents for over a decade. His research interests are beliefs about language learning, adolescence and EFL teaching, language learning through music and sociocultural theory in Applied Linguistics.

E-mail: limafsl@hotmail.com

Menu

Introduction

Theoretical Background

Adolescence: a critic time for (trans)formation

Using Music for the EFL classroom: the rhythm of knowledge

Sociocultural theory and Language Learning: Vygotskian Contributions

Learners’ beliefs about language learning: some perspectives

Methodology

The students

The activities

The instruments

Data analysis

Students’ beliefs about language learning through music

Students’ beliefs about group activities and peer collaboration

Implications for teachers

Conclusion

References

Acknowledgments

Appendix

From elementary to high school we will have teenagers in our classrooms. This specific time of their lives is characterized by several types of change, which may not be welcomed by the adolescents themselves or the ones who are with them on a regular basis. Among many interests during this period, language learning may not be the priority. Then, if our students do not cooperate or demonstrate to be willing to learn, as teachers we start looking for alternatives to deal with this issue. We study more, we attend workshops, we buy books, we try to change classroom routines and create more innovative classes.

One of these efforts has been the use of music in language classroom. Murphey (1992) claims that music is a highly motivational aspect for language learning. We consider this perspective, especially knowing that most of our students have a favorite singer or band, and through it, we may see a light at the tunnel to reach the lost sheep in classroom, in other words, motivate them to learn.

Considering that adolescents tend to seek comfort in the ones they relate to, we understand the group formation that occur in this period (Schunk & Meece, 2006), in which students find the ones to confide (Basso & Lima, 2010; Lima, 2012), and that also strengthens the interpersonal impact of the group, which can lead to indifference or indiscipline. Thus, we see in group or peer work a possibility to create an affectively appropriate environment for language learning, and we carry out activities that comprise all of these perspectives. But what about our students? How do they perceive these changes we try to establish in our classrooms? We know they like music, but what do they believe about it? We know they are teenagers, they like to be surrounded with people they can trust, so they usually prefer group activities, but what do they think about doing group activities to learn a new language? These are the questions I will attempt to address in this paper.

First, I present the theoretical background. The introductory section comprises perspectives from Psychology and Applied Linguistics regarding adolescence, learning and the challenges for the language teacher (cf. Schmuck, 1965; Basso, 2008). In the second subsection, I discuss the role of music in language learning, a cultural aspect which meets the adolescents’ interest and which has already been used as a tool for language teaching (Murphey, 1992; Medina, 1993, 2002, 2003). The third aspect is a discussion about sociocultural theory (Lantolf & Thorne, 2006) based on a vygotskian framework (John-Steiner & Mahn, 1996). I will make some comments about the role of sociocultural assumptions that have been accepted by language teachers who believe in the learning process that occur within social interaction. A process in which peers are able to assist each other through scaffolding and create new zones of proximal development (ZPD). And finally, I discuss the role of beliefs in language learning regarding their impact on peoples’ choices and outcomes.

The data came from a lesson plan designed for four English classes (75 minutes each). The participants were eight adolescent students aged between 13 and 15 years old who were studying English as a Foreign Language (EFL) in a private language school in Brazil. The classes involved oral tasks, games and the use of music. They also answered a questionnaire to assess their perspectives on the importance of language learning with music and group activities (aiming collaboration). With this study, I aim to contribute to the studies within Applied Linguistics about the process of language teaching with adolescent learners.

“I’m going through changes...”

(The Cardigans)

We have already been adolescents and the ones who have not yet, they will be! We experienced that before, we went through changes, but sometimes it seems so difficult for us, teachers to understand our students in this phase of their lives. One may argue that not everyone was rebel during that period, which is possible, because each person experience adolescence in a particular way (see Buchanan et al, 1990). There are times when the students treat you as your best friend, other times they do not even care about what you say. This period is like a merry-go-round, all their feelings go round and round and you never know what mood your student will be in the next class. Despite all these affective factors teachers have to deal on a regular basis, adolescence is also a period characterized by good things, and especially for language learning, it can be a time for developing potentials which will be really useful in adulthood.

Both in Psychology and Education, scholars emphasize that adolescence may be justified as period of stress (Arnett, 1999, 2006) due to the different kinds of changes they have to deal with. It is a period that represents a new step, when the teenager has to face the challenges of leaving behind parents’ dependency for “adulthood independence and self-sufficiency” (Zimmerman & Cleary, 2006:45). There are other kinds of changes, such as a transition from social role (Bandura, 2006), especially when the boy or girl goes to high school. These new experiences are also characterized by biological changes and the term puberty, starts to be part of teenagers’ nightmares. Hormones and its influences on mood and behavior (Begley, 2000; Buchanan, Becker & Eccles, 1992; Buchanan & Eccles, 1992) start to be a concern for parents and teachers.

This metamorphosis can be a heavy load for someone who is trying to find a place in this world while developing his or her own personal identity. Meanwhile, all these categories of change mentioned before affect domains of adolescents’ life, as suggested by Schunk & Meece (2006), for instance, (a) family relations, (b) school environment and (c) peer group affiliations. Parents claim their kids have changed, teenagers claim their parents do not understand them, and then school is the place where they find at least someone alike, someone to trust and share things that probably he or she would be too shy to talk to a parent. But at the same time, teachers may be someone who they can count on, especially the ones who are always available and maintain a good relationship with their students.

There are also good things about being a teenager. Macowski (1993), for example, mentions several studies that highlight how during teenage years students can learn a language without an accent, closer to a native speaker. This is somehow relevant for them, because sounding like a native speaker plays an important role in foreign language learners’ beliefs (see Barcelos, 2003b). Several authors have considered adolescence as an important period for developing self-efficacy beliefs (Bandura, 2006; Pajares, 2006; Schunk & Meece, 2006 Zimmerman & Cleary, 2006). This term refers to “the belief in one’s effectiveness in performing specific tasks (…) as well as by one’s actual skill” (Zimmerman & Cleary, 2006:45).They do not discard that adolescence might be a challenge due to transformations that are supposed to happen, but point out this age as a way to develop in them the desire to reach their goals and make actions in order to accomplish them (academic success, for example.)

It is important for teachers to develop awareness on the different topics regarding adolescence, in order to understand the difficult times we can have in our classrooms. But what will we do in order to motivate these students to realize that language learning at this age can be a fun and enriching experience? Bandura (2006:10) states that “adolescents need to commit themselves to goals that give them purpose and a sense of accomplishment”. Without personal commitment to something worth doing, they are unmotivated, bored or cynical”. Sometimes they might not realize the importance of learning English these days, but our classes may also seized to develop this awareness and help them to find a purpose to study EFL. One alternative has been the use of music in the EFL classroom, which is discussed in the following section.

“Without music life would be a mistake”

(Nietzsche)

Music is a cultural heritage that many people like. Its presence in our lives may start even before we are born, during pregnancy; several musicologists suggest the benefits of listening to music while expecting a baby (Howard, 1984). The baby is surrounded by different sounds. A mom’s heartbeat, the parents’ tones of voice, etc.

For teenagers, music plays an important role in their lives. It becomes part of the identity. The young person chooses a style that he relates to and acquires a whole range of characteristics to be part of a group. The hippies, the punks, they all expressed their feelings through music, not only with what they wore, but with what they sang out loud. In a period when generally the parents are no longer their favorite people, they look for their heroes, their mentors, and then, they become fans of a band, a group or a solo singer. There are also moments that can be eternalized with a song. A wedding, an achievement, a couples’ love song, a graduation day. Whenever a person hears it, he or she recalls of an entire moment. It seems like the music can get us back to a specific moment, bringing up different feelings.

In this way, it is understandable why music is a highly motivational tool for teachers (Murphey, 1992). If students like listening to it while they are at home, they would like to do that in their English class as well. Then teachers have constantly used songs to create a good atmosphere and improve vocabulary acquisition (Medina, 1993, 2000, 2002, 2003). Nevertheless, a concern discussed in Basso (1999) deserves some attention. This author claims about the use of music in EFL classes as a pretext to teach grammar. For example, if there are a lot of verbs in the past tense, you take them out, and replace with blanks, and then the student has to listen and complete the missing words. Later, the teacher explains the grammar behind the music.

But, what about the lyrics? Sometimes what students want is to understand what the song is about. Thus, I believe it is important to work with music comprehension, but considering the lyrics as a whole, not only separate vocabulary (decontextualized). Understanding the message behind a song is a chance to motivate reading, an ability that students sometimes are not very interested in. Using music in our classes represents a worthy range of possibilities for different activities (Lima; Basso, 2009). This is what I discuss in the next section. The theoretical background of sociocultural theory in which I based the activities that were used along the EFL classes.

“I was so lost by then, but with a little help from my friends…”

(Lily Allen)

Vygostky himself was not directly involved with second language learning or foreign language learning. But his studies in psychology have been constantly mentioned by several scholars (John-Steiner & Mahn, 1996; Cole & Wertsch, 2002; Smagorinski, 2007), especially the ones who study the process of language learning (Lantolf & Appel, 1994; Lantolf & Thorne, 2006; Ferreira, 2008; Basso & Lima, 2010; Lima, 2012). The importance of the sociocultural context, culture and different forms of interaction are relevant notions for understanding learning and the development of higher mental functions. Lantolf & Appel (1994, p. 05) explain that examples of higher order functions are: “logical memory, voluntary attention, conceptual thought, planning perception, problem solving, and voluntary inhibitory and disinhibitory faculties.”

The thinking process was understood in this perspective not as something that occurred only internally (that did not suffer any influence from external aspects) but considering external forces such as human interaction “between thinking bodies (humans) and between thinking bodies and objects (humans and socioculturally constructed artifacts)” (Lantolf & Appel, 1994:05).

Vygotsky explained that humans interact by using a powerful mediation tool: language. Before language acquisition, babies find their way to draw their parents’ attention by crying or shouting, and through other peoples’ stimuli and as Vygotsky (1989:32) concluded, “sometimes, the speech expresses the desires of the child; other times, it acquires the substitute role for the real act of reaching the goal”. Therefore, it is situated in a social context that he or she acquires language, in order to respond to the stimuli, feel integrated in peoples’ interaction and participate in social life.

One of his most famous notions that had a great impact on education and language studies (see Lantolf & Thorne, 2006) is the concept of Zone of Proximal Development. In his time, Vygotsky claimed the importance of considering not only the things that learners could do. According to him, there was a tendency in psychology to consider just the actual capacities of learners, in this way, most of the tests used to assess their performances considered only the ones related to independent actions, things they could do by themselves, without anyone’s help.

When first introduced the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (henceforth ZPD), he pinpointed the importance to observe the functions he defined in the embryonic state (1989:97) the ones that were in development, which now the learner needed types of assistance from other people (more capable peers) and which later would reach the level of independence (autonomy). Thus, he outlined the concept of ZDP made up with two different levels, the actual developmental state which comprises the ability to perform different tasks independently due to mental maturation of some functions. And the one that comprises the ZPD, a journey in which learners undergo from the period when they need any kind of assistance towards the autonomy (in the future).

Since then, this concept has figured in several studies related to education and language learning and has resulted in several discussions regarding the different ways people have understood and used this framework in different inquiries (cf. Lantolf & Thorne, 2006; Ferreira, 2008). In this paper, I understand the role of the ZPD concept in the language classroom as suggested by Lantolf & Thorne (2006) who explain:

“the ZDP is not only a model of the developmental process, but also a conceptual tool that educators can use to understand aspects of students’ emerging capacities that are in early stages of maturation. In this way, when used proactively, teachers using the ZPD concept as a diagnostic have potential to create conditions that may give rise to specific forms of development in the future.” (2006:267)

The activities I used in my English classes to teach EFL with music were developed based on this assumption, in which a language class is an opportunity to perceive students’ potentials and also weaknesses that I prefer to see as opportunities for future success. Following this lead, as teachers, we have to decide on what we think may be best for our students, and consider what they also believe will be effective for their learning. Also, there are the ones who think they can learn better by themselves while there are others who prefer activities in pairs or groups to foster their learning.

In 1976, Wood, Bruner and Ross published a paper on the role of peers in learning situations explaining the scaffolding construct. In the article named The role of tutoring in problem solving, the authors analyzed situations in which adults created conditions for young learners (aged 3, 4 and 5 years old) to perform tasks through tutoring. They discussed the importance of this action, stating that what makes us different, as humans, besides being able to learn is the competence “for teaching as well” (Wood, Bruner & Ross, 1976: 89). The scholars defined the term scaffolding as

“ [a] process that enables a child or novice to solve a problem, carry out a task or achieve a goal which would be beyond his unassisted efforts. This scaffolding consists essentially of the adult “controlling” those elements of the task that are initially beyond the learner’s capacity, thus permitting him to concentrate upon and complete only those elements that are within his range of competence” (p.90)

Problem solving is one of the high order functions mentioned by Vygotsky which benefits from social interaction. And then, several authors have related the scaffolding concept to the ZDP. In this pioneer article they observed adults and children, where the older peer tutored the younger one. This metaphor has been used in Education and Applied Linguistics in order to conceive learning as a process in which teachers are generally the ones who represent the more capable peer, who can guide, assist and help other students to achieve a goal in their learning process. The language teacher is the one who is capable to provide conditions for the learner to overcome a difficulty along the way. During a speaking activity for example, the teacher helps the pupil with a word that if he did not know he would probably feel uncomfortable, like many of us feel when trying to communicate and sudden we do not know a word or expression (Brown, 2001). But later, scholars have also considered the role of a classmate, who knows more, and can also be the more capable peer, assisting a classmate during a task.

In 1994, Richard Donato revisited this concept regarding language teaching and learning. He proposed then another feature of the metaphor. While helping the less capable peer, we generally saw only his side, the one who is learning with the peer who knows more. Donato (1998) contends that during interaction both people can benefit from the activity, which results in what he called collective scaffolding. In this socially mediated activity, both learners can create conditions for each other when they face a task that is beyond their competence. He concludes, through a protocol analysis of undergraduates engaging in oral tasks, that “in the process of peer scaffolding, learners can expand their own L2 knowledge and extend the linguistic development of their peers.” (Donato, 1994:52). It is important to mention that the university students in the study demonstrated to be highly motivated to engage in this kind of activity.

Ferreira (2008) also analyzed peer interaction, but her participants were not as motivated as the ones in Donato (1994). She observed the constraints in peer scaffolding with learners who attended an extracurricular language course. Different from most of the studies who stresses the benefits of peer collaboration, the author discusses about the challenges and limitations of creating this conditions for assistance in classrooms with unmotivated students and contextual factors (school materials, insufficient number of classes per week, lack of linguistic knowledge from the more capable peer, etc.).

In a similar perspective, and also studying adolescents’ interaction (during an EFL class) Basso & Lima (2010) concluded that in public schools, most of the time the teacher is the more capable peer, the one who has more knowledge and experience to help the other learners, and sometimes, the only one who can motivate the students to use the target language (or at least make an effort to do so) even when they do not feel like doing it. The authors captured in video oral tasks carried out by adolescents in a Brazilian public school for analysis. They concluded that sometimes, when both learners are not aware of their role as capable peers, they may not support each other, or if they do not feel interested they may not even engage in the task.

Considering that in Applied Linguistics there are several works regarding the study of scaffolding and peer collaboration, this paper is an attempt to understand students’ beliefs about group activities. The activities were intentionally chosen to foster oral activities in which students, while interacting, could receive assistance from a friend or the teacher. Even if we think that group activities are important, it is also relevant to know what our students believe about it. Then, in the next section I propose a reflection about the concept for beliefs in language learning, the main focus of the analysis.

“Believing, believing, I believe…”

(Keane)

Trying to understand what teachers and students believe about the process of learning languages has been a motivation for several studies in Applied Linguistics since the 1980’s. Wenden (1987) studied language learners’ beliefs about learning strategies and pointed out, in that time, that there was not enough research regarding the thinking process of learners (what they thought about the process about using strategies and how or if it influenced their choices), on the contrary, the research focused especially on their actions. Since then, there has been an increase of studies focusing this subjective domain.

The concept for beliefs I adopt in this paper comes from Barcelos (2006:18) who defines them as “a way of thinking, as reality constructions, ways to see and perceive the world and its phenomena, co-constructed in our experiences and resultant from an interactive process of interpretation and (res)signification”. According to the experiences students had with different teachers, they can reinforce some beliefs (especially the ones they hold for a long time), but also modify others if they have the chance to reflect on it.

Another reason to study this theoretical construct has been the interest to observe how actions can be influenced by a person’s thoughts. Johnson (1999:30) adds that “beliefs have a cognitive, an affective, and a behavioral component and therefore act as influences on what we know, feel and do”. Once they are formed through our experiences (Pajares, 1992) as learners and teachers, they have the potential to influence our actions, because whenever supposed to make a choice we can recall experiences that played an important role in our lives. For teachers, Richards (1998:67) explains that these concepts are formed through “a structured set of principles that are derived from experience, school practice, personality, education theory, reading, and other sources”. Hence, it is possible to understand the relevance of studying such construct.

In Brazilian Applied Linguistics, Barcelos (2007) reviewed a consistent amount of theses and dissertations that reported studies on beliefs, cognitions and representations carried out throughout a decade of research. She concluded that most of the studies focused on two main contexts: the Public Schools (PS) and the Letters course (Brazilian term to refer to a degree in English/Portuguese language and Literature). In PS there are studies that focused exclusively on teachers’ or considered the interaction system among teachers and students.

One of the few studies focusing learners was reported in Piteli (2006). She proposed an intervention inquiry in a PS classroom with students in the first year of high school. She observed the relationship between learning strategies and beliefs. Firstly, she mapped some of the students’ beliefs related to reading and strategies they already used. Then, after some classes in which she tried to develop their awareness on the use of strategies, she observed students’ conscious use of strategies and whether or not they were related to the beliefs that the pupils endorsed. She concluded that students’ learning strategies were influenced by their beliefs about reading. Piteli (2006) reinforces the use of strategies with pupils once they deal with affective aspects that raise self-confidence, which according to her, benefits the autonomy of the learner.

Beliefs have also been studied under the light of vygotskian approaches. Within a sociocultural framework, Alanen (2003) expands this idea by revisiting Vygotsky’s texts and neo-vygotskian scholars’ studies (who have related his theoretical assumptions to psychology, education and language learning). In this perspective, beliefs can be observed through interaction, as the examples that Alanen (2003) presents with the researcher and the interviewee discussing their perspectives on topics related to English language learning. She conceives beliefs as “meditational means” because they can be “used to regulate learning, problem-solving activities, thinking, etc” (2003:67). They are stable and also variable, they become part of the learner’s cognition system but in social context and activities they can be modified. And since cognition in a vygotskian framework is not seen as something isolated (inside the individual’s mind) but susceptible to the cultural context (John-Steiner & Mahn, 1996) the study of beliefs is also possible.

In this manner, studying what learners believe is also a way for proposing change in classroom routines, mainly if they are unsatisfied or unmotivated. Horwitz (1987:120) suggests that “even when student beliefs do not manifest themselves overtly in classroom dissatisfaction, they still can have a strong impact on the students’ ultimate process in language learning”. Discussing with the group or providing them the opportunity to think about their learning is also a benefit from studying beliefs. Students may be able to realize that most of their choices, that seem random or unconscious, are in fact related to what they believe they can or cannot do to learn, for example. When a group has a good relationship with the teacher it may be easier, but even with students who do not, this represents an alternative to understand what is happening in this specific context (i.e., conflicts).

For this study, I chose a group of eight adolescent pupils who had been studying together since the beginning of their course. The group, aged from 13 to 15 years old is made up of two boys and six girls. Three students came from a private school while the other four studied in a public school. They were studying EFL for six months in the beginner level. The language school was a non-franchised institute located in the state of Paraná, Brazil. The group had two classes (75 minutes each) a week (150 minutes weekly). Their syllabus was designed by the language school for the beginner and pre-intermediate levels.

The selected song for the designed activities was called That Green Gentleman (Things have changed) by the American band Panic at the disco, from their 2008 album Pretty Odd (Florida: Fueled by Ramen/Decaydance). The main theme of the song is the different kinds of changes people have in their lives, and how they may respond to that.

The lesson plan comprised four classes combining oral, written and listening activities with games and group dynamics. Considering the perspectives discussed in the theoretical framework, with the focus on adolescence and their need to feel interested in order to learn something, the kind of activities I chose was relevant to stimulate their participation and later their assessment about the classes. Table 1 presents a short description of the four classes.

Table 1 – Lesson Plans overview

| A C T I V I T I E S |

| Class and activity |

Brief description

|

| Class 1 |

Find someone who |

An interview was chosen to introduce the topic and stimulate group interaction through an oral activity. Each student received a paper containing 10 sentences which were missing the subject of the action. The aim was going around the class, ask every friend they had until they found someone who did or related to that action. If they did not, they just put an X and proceeded to the next topic. (see fig.2) |

| Class 2 |

Music: listening and lyrics comprehension |

The whole class was dedicated to the song. The students had the chance to listen to the song (more than once) and sing if they wanted to. Meanwhile, we read the lyrics together, and I tried to observe if they could recall some of the vocabulary from the interview that I took from the lyrics. We read each stanza students tried to guess what they understood by inference, and took notes on the new vocabulary. |

| Class 3 |

The Hot Potato Game 1 |

This class also focused on oral task. After understanding the lyrics, students discussed about the changes they were feeling in themselves and the importance to have friends in that time. The activity focused on friendship too. Students passed around a ball while the song was playing on the radio. I wasn’t looking at the group and when I pressed the pause button, the student with the ball had to describe the qualities of a friend on his/her left side. And then the activity went on. |

| Class 4 |

The Impressions Poster |

To end this topic it was suggested the students to create a poster with impressions they had about being a teenager. The group created two posters. In one of them they registered the bad things about a teenager (parents’ complaints, constant changes, etc) and in the other one they wrote the good things. |

(Adapted from the original lesson plan)

1 In the original version of Hot Potato when the music stopped, the last person who held the ball was out of the game. For this class, however, I made an adaption as explained in Table 1.

During this qualitative study I used a questionnaire divided in two parts and recorded one of the group dynamics from class 03 (in audio). Questionnaire part (1) had two questions which students only had to check the option they agreed with. The questions comprised beliefs about using music in language learning, and the best way to learn in class. Part (2) presented a couple of open questions. One of them was related to class 01, and students wrote their impressions about engaging in an interview activity and if they needed assistance during any step of the exercise, how they felt about it, etc. The other question was about the role of music in language learning and how students perceived it. The audio recording of the game during the third class was chosen with the purpose to analyze peer interaction among teenagers; the results of this analysis were reported in Lima & Basso (2009).

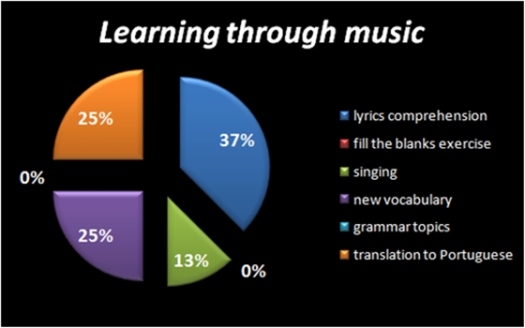

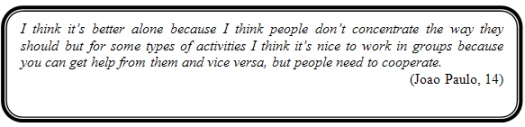

As mentioned before, music is a recurrent activity in the EFL classroom because it is easy for teachers to find (especially nowadays through internet websites and the boom of music players), and may be motivational for almost every student (Murphey, 1992). In the questionnaire, students were asked to choose what types of activities they enjoyed when teachers used activities with songs during a class. Figure (1) exemplifies their preferences.

Fig.1 – Students’ interests regarding their learning through music

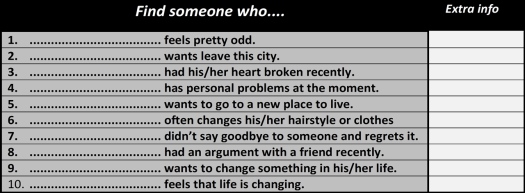

Most of the students (37%) prefer activities related to lyrics comprehension. In the other part of the questionnaire, with open questions, they were asked to explain their interests in learning through music. And again, lyrics comprehension is revealed to be their main interest whenever a teacher brings a song to the class. They believe this is the most important aspect and give similar explanations, such as:

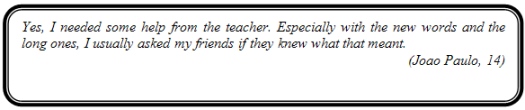

Excerpts 1 and 2

These two excerpts demonstrate that these teenagers are really curious to know the meaning of the songs that are popular at the time. Joao Paulo in his answer for example, adds that through understanding, you can also learn vocabulary and slangs. Informal language expressions are found in lyrics and students seem to enjoy learning them. Fortunately, they do not demonstrate unaware opinions towards the need to know what you are listening to. They do not care only about the rhythm or the artist, as language learners, they like to be able to understand what the song is about. In excerpt two, another student states a similar belief, and adds that knowing what you are listening to makes you comfortable to sing it.

Translating the song to their first language (Portuguese) is the second kind of activity they seem to be interested in (25%). I understand this preference related to the previous one (comprehension), because many students believe they will be able to understand the lyrics through translation. Sometimes, they like to do formal translation, sentence by sentence, and it takes too long, especially with this group that had two classes a week. An alternative is to work with deductive translation, in which the teacher asks questions for the pupils to help the understanding of sentences, and may also encourage them to infer the meaning through the context, using the words they know. In this way, they notice that if they want, they do not need (at least during an English class) to translate word by word. Also they may choose their own learning strategies, the ones they feel comfortable with (cf. WENDEN, 1987).

The fill the blanks kind of exercise was not chosen by any adolescent of this group (0%). This exercise is used generally for listening comprehension, when the teacher previously chooses some words and replaces them with blanks, and every time they listen to the song they try to complete the space with the words they hear. This is one of the most popular activities used with music, but a concern is when this is the only thing they are going to do with the song. As mentioned before, students demonstrate to be interested in lyrics comprehension; therefore, it is important to consider the lyrics as a whole, and not only isolated vocabulary (out of context). One alternative is to use this kind of exercise to introduce basic vocabulary. The teacher may choose the words that might possibly be unknown for the pupils to understand the stanzas. After this listening activity and with new vocabulary, the class may go on, and then students may be able to continue with the lyrics comprehension.

Another favorite kind of activity (25%) is the one that focus vocabulary learning. As it could be seen in the reported justifications, students also like to learn the new words. In excerpt 1, for example, the student relates lyrics comprehension to vocabulary acquisition. He states that when you understand it, you can learn new words. Some students, for example, may recognize new words from songs they have heard before and create a link between the new word and the context it is being used.

Neither of the adolescents chose grammar topics as something they like to do and learn with music. A possible reason is that grammar has been the only focus of EFL teaching (Almeida Filho, 1993, 2005; Basso, 1999), and hence, no longer one of their preferences. Basso (1999) analyzed several exercises and activities with songs which were designed by English teachers. She concluded that most of the activities tend to focus on grammar topics and structures. They involve games, group dynamics that possibly motivate students, but even with these communicative characteristics they do not emphasize communication and learning for real purposes. But instead, they are generally grammar focused, which is why the author categorized them as pseudo-communicative activities.

Singing was also something that students like to do when they have a song in the classroom (13%). Many people may feel shy to sing in public, therefore, teachers have to be sensitive when asking students to sing aloud, for example. Macowski (1993), for instance, carried out an inquiry about language learning with adolescents and noticed that they dislike exposure in the classroom, as an attempt to avoid the idea that people are laughing at them. In groups, when we perceive a more comfortable atmosphere, students may not feel embarrassed to sing it out, but with more timid people, one suggestion is to play the song louder, then no one notices his or her voice. In that manner, creating an environment where people are not intimidated to sing.

Students demonstrated positive opinions towards music in their learning process. They are more interested to understand the “message” behind the song and believe that by understanding it they can learn vocabulary. Through the types of activities they generally do, they do not feel too interested in exercises that focus grammar topics and the fill in the blanks type as shown in figure 1.

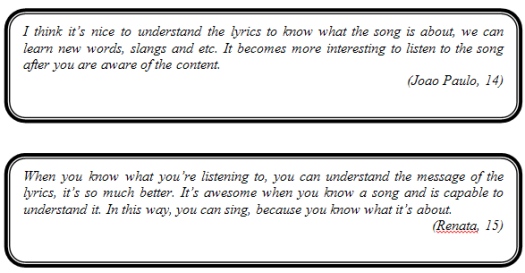

In this section, I analyze students’ beliefs about group activities and support provided by other peers. During class 1 (see table 1), the students had to ask questions to their peers in order to find out if any of their friends did or related to that action. An example of the paper each student received is presented in Fig.2.

Fig.2 – Interview Activity

For example, if a student wanted to find a friend is his class who wanted to leave the city where he or she lived (item 2) he is supposed to go to a peer and ask “Do you wanna leave this town?” or “Did you ever wanna leave this town?” among other possibilities. Once this activity does not provide the questions, which would make it much easier, it was necessary an extra time to explain to the group the type of exercise, because they had never done an activity like that. They needed some time to practice and some pupils even wrote down a few examples behind their card. The ten sentences were related to experiences and actions that were present in the lyrics I chose. The music was about changes, and since I was the teacher of an adolescent group, I expanded the theme in order to discuss the changes in their lives, especially the ones related to this period they were experiencing.

By the end of this class, they answered the questionnaire which was also a moment to think about the help that was provided for them during the task. Students were not aware of their role as capable peers who could provide a scaffolding during an interaction that would be jeopardized, for example, due to the lack of vocabulary. But it seemed relevant to study how they perceived the importance of collaboration and support during this task. While asking these questions, students needed assistance from friends and the teacher, mainly with pronunciation and question formation, as they had just the statements, and from that they had to ask the right question.

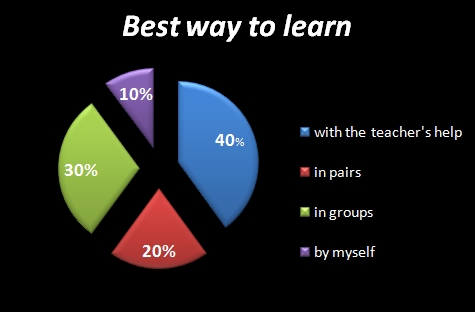

Considering the different types of interaction in the EFL classroom (i.e., teacher x student, student x student), the adolescents believe that the best way they learn through assistance is interacting with the teacher (40%). Activities in groups (with their friends) are the second best type to learn. There are also the ones who prefer activities in pairs (20%) which do not involve a lot of people working together, and force them to engage in the activity. And there is also the ones who believe they can learn better by themselves (see fig.3).

Fig.3 Preferences for learning

According to Joao Paulo the support was necessary especially with the unknown vocabulary and the sound of words. He acknowledges his teacher as the peer who provided the necessary help during the oral activity. Once the students had started the course for the first time, as beginners, they seemed to be too worried about how to pronounce the words and also understand the vocabulary in their cards. In a similar perspective, Leticia recalls that during the activity she needed help from her close friend, whenever she had a doubt she ran to her friend or the teacher, choosing the one who was available.

In a similar way to Joao Paulo, she also demonstrated an emphasis on pronunciation. When she said “…once I knew how to pronounce the words correctly I was able to do the exercise (interview)” I understood that she is expressing the comfort she felt in this oral activity by pronouncing the words and making sure she was not mistaken, because she had previously checked with someone. Without this kind of support, she could have given up the activity or refused to carry on, like some students tend to do, by claiming they do not have enough vocabulary to engage in an oral activity. If advanced learners sometimes feel embarrassed when they start an utterance, beginners may feel unmotivated since the first classes, every time they try to communicate and feel constrained due to a pronunciation of a word or a vocabulary in the target language. Feeling comfortable about making the first moves towards language learning (i.e., speaking) is important in an environment where adolescents may feel free to make mistakes and not feel ridiculous by that (see Macowski, 1993).

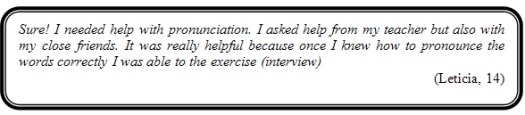

One of the students explained his point about the reason he believes it is better to learn by himself. It is also important to consider peoples’ particularities of personality, for example. There may be students who do not feel comfortable enough in oral activities, even if they are supposed to interact with the teacher (in front of the whole classroom) or with a peer nearby. Consequently, these people usually prefer individual activities.

Joao Paulo explains that during this activity some people do not concentrate enough, he even suggests he likes group activities because he can benefit from it (by helping and being helped) but knows that if the other people are not aware of that, or do not demonstrate to be interested in the goal of the activity, then there is no purpose in engaging group activity. As suggested by some scholars (ALMEIDA FILHO, 1993), activities in the EFL class need to be relevant and meaningful in order to propitiate learning experiences that can be acknowledged as valid. Adolescents hate being exposed in front of other people, because they are afraid of feeling ridiculous (MACOWSKI, 1993) and generally dislike artificial activities, where they have to answer, for instance, with the information on the book, and not with their own. It is necessary to develop this idea with the students, if they believe they can benefit from group activities or pair work they have to know how to be a peer who can assist and also be assisted during an activity. This will require more autonomy and commitment from our learners, but once they realize what they are capable of, they will able to go much further.

From the analysis presented, some issues may be considered. First, these students demonstrated positive opinions towards the use of music in language learning, which corroborates the views of several authors (Murphey, 1992; Medina, 1992, 2003; Basso ; Lima, 2009). As mentioned previously, music has the potential to draw our students’ attention, especially teenagers, who generally struggles with the idea of having to study long hours at school or demonstrate disinterest in formal learning. Maybe from activities with music, we may help them to realize and find relevance in their learning. The desire to comprehend the lyrics is their main reason, which is positive for the learners, once the activities the teacher proposes may comprise aspects that will meet their needs (Lessow-Hurley, 2003). New vocabulary and translation are other mentioned topics, and they are also related to the desire of understanding the music that is being played. In general, the interests these students have are clues to the kind of activities and materials to be designed in the future.

Having a feedback from students is a way to understand their preferences for learning, and of course the things they dislike. The fill in the blanks type of exercise, for example, is a very common activity for EFL teachers, as pointed out by Basso (1999). Then, it would be reasonable to think that once teachers are commonly designing this type of exercise with music, it is because students like it. This group, however, revealed not to like it so much, which suggests every adolescent group may respond to activities differently, and then it is important to be familiar with students’ preferences. But also, it does not mean that everything they like or want is the only best way to learn. Sometimes, they may not be aware of the potential of an activity proposed, and demonstrate not to be interested in. Thus, this is another challenge for the adolescents’ teacher, trying to intervene and make them experience that a certain activity can also be a way to learn.

In his 1965 paper, Richard Schmuck enlisted some of the concerns of contemporary Adolescents which today, even decades later, may remain familiar. The author categorized those concerns regarding the ones who generally are involved with adolescents, and who may eventually find themselves in conflict with this age group. They would be: (I) parents, (II) teachers and (III) their peers. The adolescents in his study revealed that being perceived by the teacher is important for them, in other words, they like to get attention from the teacher. Getting to know the students and the way they like to learn is also a way to make them realize that the teacher cares about them, and wants them to participate in their own learning process. This could happen when they give suggestions, but also, by being able to try the teachers’ suggestions. Knowing that they like to learn English with music is one aspect, but trying to understand what they believe about it and what interest they have, gives teachers a wider perspective of learning in the language classroom.

Another considered fact was the study of their beliefs regarding group activities and peer collaboration. Several authors (Macowski, 1993; Schmuck, 1965; Zarret & Eccles, 2006; Schunk & Meece, 2006) have discussed the role of the group during adolescence. Most of them pictured it as positive feature, because together they feel strong and embraced/accepted. Schmuck (1956), nevertheless, did not discard the peers as another source of conflict in the adolescents’ life. As a social group they may have problems with each other, but will try to work it out, since trust and acceptance are key concepts in the group.

Thus, conceiving learning as a process that occurs within a sociocultural environment in which learners may count with each other (or with the teacher), peer collaboration is expected to be always effective (see Ferreira, 2008). The data showed, in this group, that the best peer they have is the teacher. The teacher is the more capable peer for the beginner student. They trust him and ask him for help whenever they need. Working in pairs and groups is interesting for them, but their best way to learn is with the teachers’ help. Then, throughout the class I tried to maintain an environment in which they could collaborate during the tasks (teacher x students or students x students) and later have their feedback about group activities to elicit some of their beliefs. The data showed that students enjoy working in groups, especially with their close friends (but also that some of them may not be aware of their role as a peer who can scaffold one’s learning.

Lantolf and Thorne (2006: 264) corroborate this issue by stating that not “all interaction or assistance is productive, of course, and observe that many forms of ‘assistance’ in educational settings may do more to debilitate and alienate students than to encourage and aid their development”. There is a need to be careful when talking about assistance in educational settings, in order not to believe that only by putting students to work together will represent effective collaboration. In fact, it is important for them to be aware of their role and also motivated to do so, as shown in Donato (1994), a study with undergraduates (adults) learning French in the university.

In some contexts, proposing such activities require in first place the disciplinary control of the group (Ferreira, 2008). Sturm (2007) carried out a study about public school teachers’ beliefs based on vygotskian and bakhtinian assumptions. One of the beliefs she elicited from both participant teachers, is that group activities in the public school context is something very challenging and difficult for the EFL teacher because students do not cooperate, mess around and do not engage in the task. Similarly, Ferreira (2008) analyzed adolescents’ interactions during oral tasks and observed how scaffolding is constrained in many circumstances, such the lack of linguistic knowledge (from the more capable peers) among other issues. These students were participating in an extracurricular EFL course.

Basso & Lima (2010) also analyzed peer interaction with adolescents, but during oral tasks in the actual public school (EFL class). They concluded that even with the constraints, when students seem to be interested in the topic of the task; they try harder to understand what is being said and say something. And also, scaffolding in the classroom relies most on the teacher, who is always visiting pairs and groups to check if they are really doing the task. Hence, whenever working with group or pair activities, the teacher needs to be around the students, next to the ones who may forget the original idea of the task (which is promoting interaction in the target language) or the ones who may control the activity and not allow the others to participate and interact as well (see Pajares, 2006).

Language learning with adolescents is a challenging experience for teachers. They may be too interested or unmotivated at all to learn. The teacher, who wants to know his/her students better, searches for alternatives and improvements for the class. Music has been one of these aspects teachers have relied on to bring different activities for the EFL class. At the same time, group work which leads to peer collaboration is another “tool” used by teachers to engage their students to their own learning process.

This paper aimed to analyze students’ beliefs in two aspects: a) their thoughts on learning English with music and b) impressions regarding activities that involved group or pair work. The context was a private language school located in Brazil (eight adolescents in the beginner level). During four classes, I conducted a lesson plan based on a music that discussed the changes people have in their lives. This topic was addressed specifically to adolescence, which leaded to oral tasks such as an interview. The classes and syllabus were designed based on studies from Applied Linguistics and Psychology.

While learning English with music, students preferred lyrics comprehension, because they believe it is important to understand what they are listening to. Translation and new vocabulary were also mentioned as important, while grammar and fill in the blanks kind types of exercise were not very important for the group. Regarding group activity, students preferred to be assisted by the teacher, and then from their peers (in pairs or groups). Some of them even prefer to learn by themselves, but demonstrated to be aware of the benefits of group work. In general, most students seemed to benefit from group activities and enjoy it, while, there are also criticisms, such as the lack of engagement some students have to the task, such as talking or messing around.

Although adolescents’ groups are heterogeneous and opinions and beliefs may vary from classroom to classroom, more studies should be conducted. Then we could compare these study cases and observe if more adolescent groups respond to these activities in the same way, and also if they share the same beliefs with these participants. Sociocultural Theory emphasizes the role of interaction within social contexts for knowledge construction, and also is a way to understand language learning beliefs (Alanen, 2003). As I said before, teaching adolescents may be a very challenging quest, but looking for alternatives and getting to know their perspectives about it, may lead to rewarding outcomes for both teachers and their learners. Let’s go on with the challenge!

I would like to thank Dr. Edcleia A. Basso (Universidade Estadual do Paraná, Brazil) for her insightful suggestions during data collection and my colleague and friend Douglas Candido Ribeiro (M.Sc, Universidade Federal de Viçosa) for the comments on an earlier version of this paper.

I would like to thank Dr. Edcleia A. Basso (Universidade Estadual do Paraná, Brazil) for her insightful suggestions during data collection and my colleague and friend Douglas Candido Ribeiro (M.Sc, Universidade Federal de Viçosa) for the comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Alanen, R. (2003). A sociocultural approach to young language learners’ beliefs about language learning. In: Kalaja; P; Barcelos, A. M. F. (Ed.). Beliefs about SLA: new research approaches. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 55-86.

Almeida Filho, J.C.P. (1993). Dimensões Comunicativas no Ensino de Línguas. (Communicative Dimensions in Language Teaching) Campinas, SP: Pontes.

Arnett, J. J. (1999). Adolescent storm and stress, reconsidered. American Psychologist,

54, 317–326.

Bandura, A. (2006). Adolescent development from an agentic perspective. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.). Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing, pp. 1-43.

Barcelos, A.M.F (2004). Crenças sobre aprendizagem de línguas, Linguística Aplicada e ensino de línguas. Linguagem & Ensino, vol.7, No.1, p.123-156.

Barcelos, A.M.F. (2006) Cognição de Professores e Alunos: tendências recentes na pesquisa de crenças sobre ensino e aprendizagem de línguas. In Vieira-Abrahão, MH. Barcelos, A.M.F (orgs.). Crenças e Ensino de Línguas – foco no professor, no aluno e formação de professores. Campinas, SP: Pontes Editores.

Basso, E.A. (2008). Adolescentes e a aprendizagem de uma Língua Estrangeira: Características, Percepções e Estratégias. In: Rocha C.H. & Basso, E.A (Org) Ensinar e Aprender Língua Estrangeira nas diferentes idades: reflexões para professores e formadores. São Carlos, SP: Claraluz.

Basso, E.A. (1999) Back to the future: aulas comunicativas ou formais? In: XII CELLIP – Centro de Estudos Linguísticos e Literários do Paraná, 1999, Foz do Iguaçu.

Basso, E.A & Lima, F.S. (2010). A colaboração entre pares em uma turma de adolescentes aprendendo inglês na escola pública. Revista Horizontes de Linguística Aplicada. v. 9, n.1, p. 4-25.

Buchanan. C.M; Eccles, J.S; Flanagan, C. Midgley, C.; Feldlaufer, H; Harold, R.D. (1990). Parents' and teachers' beliefs about adolescents: Effects of sex and experience. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 19 (4): 363-394.

Begley, S. (2000). Getting inside a teen brain: Hormones aren’t the only reason adolescents act crazy. Their gray matter differs from children’s and adults’. Newsweek, 58–59.

Brown, H. D. Principles of language learning and teaching. 3rd edition. White Plains: Longman. 2001.

Buchanan. C.M; Becker, J.B; Eccles, J.S. (1992). Are adolescents the victims of Raging Hormones: Evidence of Hormones on Moods and Behavior at Adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, vol.111, No 1, 62-107.

Buchanan, C.M; Eccles, J.S. (1992). Hormones and Behavior at Early Adolescence: A Theoretical Overview. Symposium presented at the biennial meetings of the Society for Research on Adolescence, Washington, D.C, March, 1992.

Donato, R. (1994). Collective Scaffolding in Second Language Learning. In Lantolf, J.P & Appel, G. Vygotskian approaches to second language research. Ablex Publishing Corporation. 1994.

Ferreira, M.M. (2008). Constraints to peer scaffolding. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada. Campinas, v. 47, p. 9-29.

Howards, W. (1984). A Música e a Criança (The music and the child) . São Paulo: Summus.

Horwitz, E.K. (1987). Surveying beliefs about language learning. In: Wenden, A. & Rubin, J. Learner Strategies in Language Learning. Prentice Hall Regents.

John-Steiner, V. & Mahn, H. (1996). Sociocultural Approaches to Learning and Development: A Vygotskian Framework. Educational Psychologist, 31 (3/4).

Johnson, K. (2006). The sociocultural turn and its challenges for second language teacher education. TESOL QUARTERLY, v. 40, n.1, p. 235-257.

Johnson, K. (1999) Understanding Language Teaching: Reasoning in Action. Boston: Heinle and Heinle Publishing Company, 1999.

Lantolf, J.P. & Appel, G. (1994). Vygotskian Approaches to Second Language research. Norwood, New Jersey: Ablex Publishing.

Lantolf, J.P. & Thorne, S. L. (2006). Sociocultural Theory and the Genesis of Second Language Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Lessow-Hurley, J. (2003). Meeting the needs of the Second Language Learner. ASCD: Alexandrina.

Lima, F. S.; Basso, E. A. (2009) Adolescentes aprendendo inglês com música: nos embalos da zona de desenvolvimento proximal. IV EPCT – Anais do IV Encontro de Produção Científica e Tecnológica. Campo Mourão: Editora da Fecilcam.

Lima, F.S. (2012). Signs of Change in Adolescents’ Beliefs about Learning English in Public School: a Sociocultural Perspective. (Unpub Master Thesis). Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Minas Gerais, 2012.

Macowski, E.A.B (1993). A construção do ensino/ aprendizagem de Língua Estrangeira com adolescentes. (Unpub Master Thesis). Campinas: UNICAMP 1993.

Medina, S. L. (1993). The effect of music on second language vocabulary acquisition. National Network for Early Language Learning, 6 (3), 1-8.

Medina, S.L. (2000). The effects of music upon second language vocabulary acquisition. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 352 834).

Medina, S.L. (2002). Using music to enhance second language acquisition: From theory to practice. In Lalas, J. & Lee, S. (Eds.), Language, literacy, and academic development for English language learners. Boston: Pearson Education Publishing.

Medina, S.L. (2003). Acquiring vocabulary through story-songs. MEXTESOL Journal, 26 (1), 7- 10.

Murphey, T. (1992) Music & Song. Oxford, England. Oxford University Press.

Pajares, F. (2006) Self-efficacy during childhood and adolescence – Implications for Teacher and Parents. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.). Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

Pajares, F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, v. 62, n. 3.

Piteli, M. L. (2006) A leitura em língua estrangeira em um contexto de escola pública: relação entre crenças e estratégias de aprendizagem. Dissertação. (Unpub Master thesis). UNESP, São José do Rio Preto, 2006.

Richards, J.C. (1998) Teacher Beliefs and decision making In: Richards, J.C. (ed). Beyond Training. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schmuck. R. (1965) Contemporary concerns of Adolescents. NASSP Bulletin, 1965.

Schunk, D.H & Meece, J.L (2006). Self-efficacy development in adolescents. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.). Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

Smagorinski, P. (2007) Vygotsky and the Social Dynamics of Classrooms. English Journal. Vol.97, No 2.

Sturm, L. (2007). As crenças de professores de inglês de escola pública e os efeitos na sua prática: um estudo de caso. 2007. Tese (Doutorado em Letras) - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1989a). Pensamento e Linguagem. 2.ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes.

Vygotsky, L.S.(1989b). A Formação Social da Mente. 3.ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. & Ross, G. (1976). The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17, pp 89-100.

Zarret, N. & Eccles, J. (2006). The passage to adulthood: Challenges of late adolescence. New Directions for Youth Development. No 111, 13-28. DOI: 10.1002/yd.179

Zimmerman, B.J & Cleary, T.J. (2006). Adolescent’s devolpment of Personal Agency – the role of self-efficacy beliefs and self-regulatory skills. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.). Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

Questionnaire

In each question, choose one alternative that best describe your opinion.

1) The best way to learn with music is by/through…

2) The best way to learn in class, for me is…

For the next questions I would like you to feel free to express your opinion…

(About the interview activity)

3) Did you feel the necessity to be assisted by a friend or the teacher during the activity? How was it? Do you prefer this kind of assistance? Make comments.

(About music)

4) Do you like learning English with music? What aspect do you believe it is important to consider when there is music in your English class? Please, justify.

Thanks a lot! ;D

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching through Music and Visual Art course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching English Through Multiple Intelligences course at Pilgrims website.

|