Editorial

This article was first published in Modern English Teacher, Vol. 20/4, April 2011

Making Grammar Connections, Increasing Connectedness

Simon Mumford, Turkey

Simon Mumford currently teaches EAP at Izmir University of Economics, Turkey. He has written many classroom activities on themes such as story-telling, visuals, drilling, reading aloud, vocabulary and is especially interested in the creative teaching of grammar. E-mail: simon.mumford@ieu.edu.tr

Menu

Introduction

Present perfect + indefinite article vs past + definite article

Interrogative pronouns vs relative pronouns

Going to go to

Used to vs Present Perfect

Used to and comparatives

Comparatives and superlatives, and jobs and functions

Double marking and learner error

Future inflections

Contractions and reductions

Phrasal verbs and letter combinations

Irregularities in noun and verb forms

Irregular forms- the top of the pyramid

Conclusion

Reference

Although initial presentation of grammatical items in isolation is far from being universally accepted as the best way of teaching, it is still a frequently used methodology in many contexts. However, as we know, language is more than a collection of discrete grammatical and lexical items, and it is important for students to see the whole as well as the parts.

One possible way of increasing the sense of connectedness across language may be to look for parallels and make links that are not normally made. We know that the brain seems to like patterns and tends to make sense of new information in terms of what it already knows. Generally speaking, therefore, the more ways that new information is connected to previously learnt information, the more likely it is to be understood and remembered. In other words, there are potential mnemonic benefits of relating two or more language items, even if the connection between them is not immediately obvious. The understanding of one can support the understanding of the other. Here are some examples of ways this concept could work in practice.

A: Have you ever seen a ghost? B: Yes, I have! A: What colour was the ghost? B: White.

Practise the dialogue, then point out that the speaker A uses present perfect tense and an indefinite article (a/an) because he has neither a definite time nor ghost in mind. Speaker B uses past tense for a definite time (the time she saw it) and the definite article (the) for a definite ghost, (the one she saw). We can further extend this parallel to include the type of question asked, yes/no for indefinite, and wh- for definite. Thus we can point out the definite/indefinite tendencies as follows:

| tense | article | question |

| indefinite | present perfect (Have you seen...) | a (ghost) | yes/no |

| definite | past (What colour was...) | the (ghost) | wh- |

This can be practised with other cues:

A: Have you ever seen a wolf/lion/bat/monkey/Rolls-Royce/shark/dinosaur etc.

B: Yes, I have.

A: What colour was the shark?/Where was the dinosaur?/When did you the wolf?/What was the monkey doing?

B: The shark was blue./The dinosaur was on TV./I saw the wolf last year./The monkey was sleeping.

Which has two main functions, as an interrogative pronoun, eg Which car was it?, and a relative pronoun, eg The car which we saw yesterday. We usually see these as separate, but in the following example we can see the relationship:

A: Which car do you like best? B: The car which we saw yesterday.

Inverting the order (which car→car which) brings about the opposite function, a question becomes an answer, identifying the car. This can be practised in short dialogues:

A: Which house/dog/elephant/mobile/magazine/train/coffee/polish/cake would you like? B: The house (etc) which (was advertised in the newspaper).

In the phrase (be) going to go to, the two occurences of word to are homonyms, that is, they have different meanings. The first to is part of the infinitive, and the second, a preposition. However, in a sense, they both have direction. The first one moves forward in time, since the to infinitive is often associated with future meaning (cf. intend to, plan to, be about to). The second, the preposition to, has direction in space. Thus, I’m going to go to London combines movement in time and space. This is logical because much of our planning is inevitably concerned with travel. In addition, the going to go to structure is a memorable one because it has strong alliteration and rhyme.

In a sense, the structure used to and Present Perfect can be considered opposites, because the Present Perfect stresses continuity, whereas used to indicates change. The structures can be represented by symbols as follows:

| structure | symbol | |

| I’ve always played | → (continuing) | continuity |

| I’ve never played | 0 (no symbol) | continuity |

| I used to play | + - (Positive then negative, an activity has been discontinued) | change |

| I didn’t use* to play | - + (Negative then positive, an activity has started) | change |

*Didn’t used/didn’t use to are both used in the negative form, however, it is not usually possible to distinguish these in speech (Carter & McCarthy, 2006, p 661).

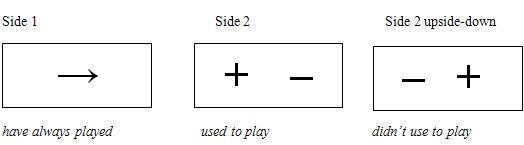

This can be developed into an activity. In pairs, student A asks questions, eg Do you play football/tennis. Can you swim/speak English? Student B replies by holding up a piece of paper with the appropriate symbols, as shown below. Side 1 of the paper has an arrow representing Present Perfect for continuity. Side 2 has a plus and minus sign, representing a change from positive to negative, representing used to. Note that holding side 2 upside-down reverses this change, representing didn’t use to.

Student A has to interpret the paper, for example:

A: Do you ever go camping?

B: (shows side 2, normal position)

A: Oh, you used to.

Or

B: (shows side 2, upside-down)

A: You do now, but you didn’t use to.

B: (shows side1)

A: Oh, you’ve always played.

A: Do you like singing?

B: (no symbol)

A: I see, you have never liked singing.

The connection between the structure used to and comparatives is logical because used to implies a difference between the past and present. The difference can be contrasted using a comparative, as shown in this dialogue:

A: You’ve put on weight. B: Yes, I used to be slimmer (than I am now).

Give students the first sentence and ask for a reply with used to and a comparative. Then let them invent and practise other dialogues describing changes. Examples:

You’ve lost hair/Yes, it used to be thicker; You’ve slowed down/Yes, I used to drive faster; Your eyesight’s getting bad/Yes, I used to see better; The river’s very clean/Yes, it used to be dirtier; Petrol’s so expensive now/Yes, it used to be much cheaper; John hasn’t got much money these days/Yes, he used to be richer; You’ve lost weight/Yes, I used to be heavier; Jane looks sad/Yes, she used to be happier.

Note also the parallels between the spoken forms used to /ju:stə/ and faster/fa:stə/.

The suffix –er has two roles in English, to make comparatives (faster, older) and to make verbs/nouns/adjectives into words that represent people in a certain occupation (manager, runner) or with certain characteristics (teenager, pensioner). We can therefore use both types of word while contrasting occupations/roles:

A runner is faster than a swimmer. A pensioner is older than a teenager. A weightlifter is stronger than a waiter. A farmer works harder than a begger. A basketball player is taller than a table-tennis player. A footballer runs further than a golfer. An office worker is freer than a prisoner.

This parallel can be taken a stage further, because the superlative suffix –est, (longest, fastest) sounds identical to the suffix -ist, which also denotes people who have a certain job or function (typist, dentist), because e is pronounced as i when unstressed. Here are some examples of combinations of these two forms:

the greatest artist, the tallest typist, the best biologist, the nicest scientist, the cleverest chemist, the coolest criminologist, the funniest florist, the happiest novelist, the shortest naturalist

Students can have fun inventing their own rhyming comparisons of two occupations, as well as superlatives for occupations, thus linking these grammatical categories for potential mnemonic benefits.

In English, aspects of meaning need only be marked once, and marking something more than once is a common source of error. A well-known example is the double negative: *I didn’t never go there. Other mistakes include the double marking of comparatives: *more faster, the double simple present: *I am go, and the double plural: *childrens. It is even possible to argue that errors such as * the London are double marked, since London is already marked as a unique noun by the fact that it starts with a capital letter, and therefore the is unnecessary. Point out to students the principle that, in English, once is enough. (*=incorrect forms).

We all know that regular past tense verbs are inflected with –ed. However, it is possible to argue that nouns and pronouns are inflected for the future, eg I’ll see you tomorrow. Although will is associated grammatically with the main verb, in its contracted form, it is strongly associated with the noun/pronoun. Therefore, in a sense, all pronouns and nouns can be said to have a future form: he’ll, Jane’ll, the car’ll, next week’ll, Britain’ll, the computer’ll.

This way of thinking may help students see that it is perfectly natural to add ‘ll to any noun/pronoun. In fact, in most circumstances, it is a lot more natural to use ‘ll than will. According to Carter & McCarthy (2006, p.650), the contracted form is about three times more common in spoken language than the full form. They also note that when making arrangements and decisions, the contracted form is usually the only form that can be used, and state that ‘‘ll can be seen as an independent form’ (p. 632). It is therefore important that students become comfortable with the contracted form. Students have no problem in saying we-wheel, cat-cattle, car-Karl. It is equally natural to say we-we’ll, cat-cat’ll, car-car’ll. This parallel, which sees ‘ll as a suffix to a word rather than a separate word, may help students see that in pronunciation, it is more part of the noun/pronoun than the verb.

Generally speaking, the less we say, the more informal we become. This covers all kinds of abbreviations, ellipsis, contractions and reductions. In the following pair of sentences, B is much more informal.

A Elizabeth has found a friend who she likes a lot.

B Liz’s found a friend she likes a lot.

Shortened names, contractions and zero relatives are the three features of the above example. Abbrevations and other reduced forms can also be used. Give students some more sentence As to edit down, or, sentence Bs restore to their full form. Examples:

A Johnathan has got a great new job with the European Union

B John’s got a great new job with the EU.

A The British Broadcasting Corporation are looking for a new series in order to improve ratings.

B The BBC’re looking for a new series to improve ratings.

A I am going to apply for that English for Academic Purposes post at the university as soon as possible.

B I’m gonna apply for that EAP post at the uni. asap.

Some verbs consist of two words, a verb and an adverbial particle, which join to create a meaning completely unpredictable from the individual words, eg go off meaning explode. Similarly, some pairs of letters can combine in ways to create sounds that are totally different from the two individual letters. The word repetition is interesting because it contains two t+i combinations, the first is pronounced as expected, and the second, as sh. A parallel phrasal verb sentence is: He went off to work before the bomb went off, where the first went off has a predictable meaning, and the second went off is unpredictable.

In each of the following sentences, students have to find a pair of phrasal verbs with the same form but different meanings, eg live on an island/live on fish. In each sentence they also have to look for corresponding letter combinations: either the same combination of letters which has different sounds, eg some/home, or different combinations which have the same sound eg school/dusk). They also have to say which one of the pairs of word groups and letter groups is predictable and unpredictable in each case. Answers are underlined: p=predictable, u= unpredictable.

- They lived on (p) an island (u) for a year, and they lived on (u) coconuts and fish (p).

- While the the mansion (u) was broken into (u), the vase was broken into (p) six (p) pieces.

- As soon (p) as we passed out (p) of the hall, I saw blood (u) and passed out (u).

- The hook (p) dropped off (p) the wall and woke Jim, who (u) had dropped off (u).

- They had to stand for (p) an hour (u) waiting to go in. How do our (p) people stand for (u) such treatment?

- Stand by (p) the door, Leo (p). We need someone to stand by (u) in case people (u) try to get in without tickets.

- I was running across (p) the park at dusk (p), and I ran across (u) Bob from school (u).

- The chemist (u) should keep his key on (p) a chain (p) , because he keeps on (u) losing it.

- I wanted to call on (u) Reg (u), but I got a call on (p) my mobile begging (p) me to come home.

- They were going into (u) some (u) details about the new home (p) project, so I went into (p) the meeting early.

In spelling, as with words in phrasal verbs, combinations can produce unexpected results. It may be worth pointing out to students that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts in such cases.

Irregularities are a problem because of their seeming unpredictability, but even across irregularities there are patterns and parallels. When comparing irregular plurals and past/participle forms, for example, four patterns can be seen.

| irregular past tense /past participle | irregular plural | difference from regular | |

| 1. | sit-sat-sat | foot-feet | change in vowel sound |

| 2. | put-put-put | sheep-sheep | no change in form |

| 3. | write-(wrote)-written | child-children | syllable added, first vowel sound shortened |

| 4. | wait-waited | bus-buses | extra syllable added because of similarity between consonant sounds |

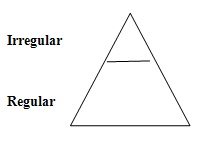

Students may get the impression that there are a lot of irregular forms in English. The truth is that while high frequency forms are often irregular, the overwhelming majority of forms are regular. Irregular forms of verbs (eg sit-sat-sat), plural nouns (man-men, child-children), adverbs (well, worse, better, fast) and even cardinal numbers (first, second, third) are among the most frequent words in their class. They are at the top of the pyramid. However, this does not mean they are typical, in fact, the majority of the rest of the pyramid is likely to be regular.

Grammar items tend to be presented isolation, and later, contrasted with other directly related items, eg Past tense vs Present Perfect, comparatives vs superlatives. In the system of grammar, however, there are many potential connections and parallels that are not usually considered.

To avoid possible confusion, we should be careful to stress that often, such connections are not grammatical rules in the normal sense, but simply interesting correspondences. Our task, as teachers, will be to decide which connections are the most useful for students, and how to exploit them. Rather than using them as presentation techniques, such parallels will probably be best employed when students already have a good grasp of the individual grammar items. By highlighting some of these links, we could help our students to reach a greater awareness of grammatical tendencies, and exploit correspondences in form, meaning and pronunciation for mnemonic benefits.

Carter, R. and McCarthy, M. (2006) Cambridge grammar of English.

Please check the English Language Improvement for Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology for Teaching English Spoken Grammar course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|