Implementing Differentiated Grammar Instruction in a Traditional Language Class

Anne-Sophie Bernard, Luxembourg

Anne-Sophie Bernard has been an EFL teacher in Luxembourg for 6 years. She is currently working at the “Atert-Lycée Rédange” high school.

E-mail: anne-sophie.bernard@education.lu

Menu

Introduction

What is differentiation?

Key principles of differentiation

Differentiated classroom management

Differentiated grammar instruction

Conclusion

References

School is meant to enable each student to make continuous progress. Teachers are becoming more and more aware of this matter and the importance of catering to their students’ individual needs by proactively planning and adapting their teaching accordingly. Nevertheless, despite the best of intentions, it is not always easy to find ways of adapting one’s teaching to every single student’s needs in terms of academic, social and emotional needs, as well as prior knowledge and learning strategies. The objective of this piece of work is not to evaluate the effectiveness of differentiated instruction on learners’ knowledge and skills. It takes for granted that differentiation is an effective way of enabling each student to make continuous progress and therefore focuses on its practical implementation on an everyday basis.

My project was aimed at identifying differentiating tools that can be realistically applied in the traditional English class given the limitations of space, time, resources, classroom management, curriculum standards, assessment, as well as the teacher’s and students’ beliefs and engagement. As it was carried out in a 10TG, it mainly focused on differentiated grammar instruction. This report will first provide the reader with theoretical insight into the concept of differentiation and then suggest a concrete action plan which can be used to integrate differentiation in the traditional language class.

Differentiated instruction is based on the principles of the constructivist approach which suggests that successful learning can only happen if the learning context is adapted to every student’s needs in terms of interests, learning profiles (hereafter used as an umbrella term for learning styles, socioeconomic and family factors, learning pace, gender influences, cultural and ethnic influences, student attitudes and beliefs, and confidence in learning) and readiness (hereafter used as an umbrella term for prior knowledge and proficiency as well as cognitive abilities).

Nevertheless, differentiated instruction is no individualised instruction. It does not offer a personalised option for every single learner. Such individualised instruction would lead teachers to exhaustion and make learning fragmented and irrelevant (Tomlinson 2001). Moreover, teachers do not need to differentiate all elements in all possible ways. Differentiated instruction makes sense only when there is a student need and the teacher is convinced that it will increase the likelihood that the student will be better engaged and/or understand and use an essential skill more thoroughly than if it had not been differentiated (Tomlinson 1999). Whole-class instruction can sometimes be more efficient and provides opportunities to build a learning community through common activities and experiences, to introduce new units/topics/skills/concepts, and conduct discussions on important content (Tomlinson 2001, Heacox 2001).

According to Roberts and Inman (2008), the differentiated classroom must establish a respect for diversity by acknowledging and celebrating differences between individuals, but still maintain high expectations levelled according to the individual learners and finally, generate openness. These three principles are all two-fold: they involve both teacher and student awareness. Not only do the teachers observe these three principles but they also make sure that students respect differences, have high expectations for themselves and show openness towards their differences and the concept of differentiation itself.

Based upon the principle that it provides every student with ongoing opportunities to make continuous progress, differentiation should not be considered as a teaching strategy to implement once in a while in the traditional classroom when there is extra time to experiment with new strategies. Differentiated instruction is more like an approach or a way of life in the classroom. Instead of directly focusing on what to do in the classroom, it is wisest to think about our conception of learning and teaching first. If teachers think in terms of differentiation, every strategy implemented becomes part of a coherent whole. When talking about differentiated learning and instruction, three questions need to be addressed (Tomlinson 1999):

- “Differentiate What?” refers to the curriculum element that is differentiated. Teachers can differentiate the content (i.e. what the students will learn and the material used to support that learning), the process or instructional strategies (i.e. the way the students will learn) and the product (i.e. how the students will demonstrate what they have learned). Tomlinson adds the differentiation of the learning environment, which she defines as “the classroom conditions that set the tone and expectations of learning” (1999, p.48).

- “Differentiate How?” refers to the specific student needs which differentiated instruction addresses. Differentiation can cater to learners’ needs in terms of interests, readiness and learning profiles. Heacox (2001) adds the socioeconomic and family factors, as well as gender influences and cultural or ethnic influences as factors to take into account when deciding on how to differentiate a unit.

- “Differentiate Why?” can be summed up as providing students with equal opportunities to make continuous progress by catering to their specific needs. In the traditional classroom, instruction is generally based on the “no child left behind” principle according to which all students should be given similar treatment in order to reach and demonstrate equal standards of proficiency. Experts in differentiated instruction point out the contradiction in most educational systems which impose equality of treatment and opportunity on the one hand and the celebration and valuing of difference on the other (Smith 2006). Discussions about differentiation typically turn to the subject of fairness and equality because in the differentiated classroom, not all students do the same thing at the same time. As Roberts & Inman (2008) point out, fairness does not consist in giving every student the opportunity to do the same thing but in providing each child with ongoing opportunities to make continuous progress by being involved and challenged according to his or her own characteristics and needs.

The fear of losing control of student behaviour can lead some teachers to avoid trying out differentiated instruction. Yet numerous experts in differentiation and classroom management assert that fewer cases of misbehaviour occur when students are offered engaging learning opportunities which match their particular needs. They also point out that teachers exert more leadership in their differentiated classroom because they show more tolerance towards movement and noise and are thus more respected by their students.

French educationalist Meirieu (1995) adds a note of caution to this optimistic view by warning teachers of the danger of founding differentiated instruction on the simplistic assumption that differentiated tasks will engage students more and thus make them stay more on task and misbehave less. He insists on the fact that teachers need to develop specific skills in classroom management in order to keep control of student behaviour and successfully manage the learning that occurs in their classroom. As Roberts & Inman point out, classroom management must be intentional and be seen as completely natural and thus predictable for the students.

A very first step to differentiate efficiently and successfully is to ensure a classroom climate in which students feel comfortable. Two attitudes are possible. Heacox (2001) holds the view that differentiation should be made “invisible” to avoid hurt feelings or resentment. According to her, the key to making differentiation invisible is to vary the instructional strategies so that the students cannot know from past experiences if they are in the “low” or in the “high” group. Other experts like Hume (2009) or Roberts & Inman (2008) insist on the importance of making differentiation “visible” by establishing a dialogue with the students around the concept of differentiation itself. I decided to adopt this second attitude by putting into practice the following principles:

- Creating a zone of comfort around the concept of differentiation by being involved in an ongoing discussion with the students about the way they learn and the aim of school (i.e. making continuous progress). According to Hume (2009), metacognition is both the aim of and the key to successful differentiation. Furthermore, if students know why and how to experience successful differentiation, they will be able to back up their teacher in his or her attempt to “change the rules” of more traditional methods of teaching.

- Creating a risk-free supportive environment in which students feel safe and secure enough to acknowledge and express their understanding or lack of understanding. As Gregory and Chapman put it, “students who know and respect each other are more tolerant of differences and more comfortable when tasks are different” (2006, p.18).

- Defining a flexible and reasonable set of rules. Good intentions are not enough. If teachers change the rules of their teaching methods, they must make sure that students are aware that they are still rules (Roberts & Inman 2008; Tomlinson 1999). Redefining one’s role as a teacher is not an easy task, all the more since the students need to understand and accept the redefinition of their own role as well. On the other hand, Rey (2007) insists on the importance of the validity of classroom rules. The latter should not exist for their own sake but serve pedagogical purposes. For instance, teachers must be aware that student movement and talking are part of efficient differentiated instruction and are by no means signs of flawed classroom management.

- Fostering learner autonomy, as it is unrealistic to believe that teachers alone can cater to all their students’ needs in a differentiated classroom. Teachers should bear in mind that differentiated instruction is no individualised instruction and that they are not the only helping resource in class. In the differentiated classroom, dialogue and pair/group work as well as the use of teaching resources (internet, books, keys to exercises, dictionaries, etc.) are a sine qua non. Working with instruction sheets and answer sheets can also be useful to save time and energy for better student autonomy and efficiency.

- Fostering student choice. In order to guide the students in their autonomy, they must be encouraged to and taught how to develop a sense of responsibility and take an active part in making decisions about their own learning (Scharle & Szabó 2000; Gregory & Chapman 2006). Moreover, teenage students want to have power in the classroom and when this desire is fulfilled, motivation and engagement are increased (Heacox 2009; Hume 2009). A common way of empowering students is to provide students with choice opportunities by still being “very intentional about the options provided” (Roberts & Inman 2008, p.103). This use of “controlled choice” (i.e. teachers determine when and what their students may choose from) does not only motivate students to learn and to actively engage in their learning but also enables them to develop their self-awareness (i.e. knowing their strengths, weaknesses and needs), self-esteem and confidence and makes them acquire the life-long competence of making the right decisions for themselves (Heacox 2009; Hume 2009). Although she agrees on the essential role of student choice in differentiated instruction, Hume (2009) yet warns the teachers against the limits of the empowerment of teenagers. Interestingly, she points out that some students tend to be more concerned with peer pressure and their need to belong and assert themselves in a group rather than to make the right decision for themselves or to get the job done. She also points out that some teenage learners do not have the necessary degree of self-awareness and/or self-confidence to be able to make the right choices in their learning process. Whether they are already able to make the right choices or not, providing students with choice opportunities still enables them get to know themselves better and learn how to take decisions accordingly, thus increasing their “employability” by helping them grow up and become resourceful individuals willing and able to accept appropriate challenges and take on their responsibilities (Hume 2009).

- Avoiding unnecessary movement by creating heterogeneous groups whose members can help each other without having to stand up. This implies to plan the preassessment test sufficiently in advance (i.e. before a weekend) to allow time for planning efficient groups at home.

In the framework of this project, grammar instruction was differentiated both in terms of content and process. The following points will describe the different steps of an action plan that can be used to integrate differentiation according to readiness into the flow of actions, ranging from standards to summative assessment (based on Heacox 2001; Heacox 2009; Gregory & Chapman 2006; Linser & Paradies 2001).

1. Defining academic standards

It is crucial to first select the prescribed standards in the curriculum that all the students should know, understand or be able to do after the learning experience.

Example:

Every student should be able to use the present perfect simple in focus-on-form exercises as well as in guided and free written productions.

2. Determining summative assessment strategies

This second step consists in determining the assessment strategies that will be used to gather evidence of student learning and to make sure that curriculum, assessment and instruction are aligned. Beginning with the end in mind helps to shape the instruction plan accordingly, so that summative assessment reflects the activities that students engaged in during the unit (Wiggins 2005).

Example:

The summative test will contain a “mixed tenses exercise” and a “free writing task” in which the students will have to use the present perfect simple. Moreover, the students will have to hand in a recorded interview in which they are asked to use the present perfect simple.

3. Identifying the students’ needs (preassessment)

Ongoing assessment informs teachers on how to adjust their teaching for a better understanding and/or engagement on the side of the learners. One particular type of assessment specific to differentiation is preassessment, which plays a critical role in teachers’ ability to differentiate instruction. Preassessment is defined as a “diagnosis” which provides teachers with opportunities to get to know and to understand their students, their strengths and weaknesses, interests, misconceptions and prior knowledge from past experiences. The data gathered from systematic and meaningful preassessment, associated with formative and summative assessment, will help the teacher to make meaningful decisions about an appropriate timeline for instruction, classroom materials, activities and end-of-the-unit assessments. Moreover, preassessment provides students with examples of the work that will be expected of them during the unit and in the summative assessment.

Out of fear of losing too much time, teachers might be tempted to replace preassessment by their teacher instincts. After a few months, teachers might think they know their students well enough to instinctively decide what groups or activities they should be assigned to. Tomlinson values the idea of instinct, but insists on the fact that “intuition begins the process” and needs to be refined by means of deeper knowledge of differentiation techniques and strategies (Tomlinson 2001, p.45).

There is strong agreement among – especially American – experts to consider preassessment as a requisite step to prove the need for differentiated learning and to be accountable for decisions based on reliable data and not on whimsy. French educationalist Meirieu (1995) criticises this approach for its lack of intellectual honesty. According to him, it is wrong to hold the view that it is possible to identify learner’s needs before even starting to work with them. As a result, Meirieu highlights a different approach, which admits that preassessment cannot identify learners’ needs with absolute accuracy and that those needs will be highlighted in the course of the unit, through trial and error as well as a constructive dialogue with the learner.

As far as I am concerned, I realised that students’ performances in the preassessment are extremely difficult to analyse as it is very difficult to realise whether a student needs to be taught from scratch or only needs a quick reminder to recover his or her high level of proficiency. This is a clear limit of preassessment in foreign language classes, and especially in the EST, where readiness is also defined in terms of “ability to recall information” and “learning pace”. Nevertheless, preassessment tests remain useful to create a need and thus engage the students in the lesson. Indeed, they enable teachers to show to their students that they do not master a specific grammar point completely and that they still need to revise it. In my opinion, in order to be more representative of the students’ actual differences, preassessment should follow a first lesson consisting in whole-class grammar instruction, which allows the average- and high-ability students to recall prior knowledge and/or integrate new knowledge quickly and directly move on to more challenging tasks. Weaker students are then given further explanations in a more individualised and thus efficient way after the preassessment, when they are at Station 1 (see below).

Example:

The students are introduced to the “present perfect simple”. This brief undifferentiated lesson is then followed by a preassessment test consisting in 4 focus-on-form exercises with levels ranging from Station 1 to Station 2. The exercises are collected at the end of the lesson to be corrected by the teacher.

4. Individualising the learning goals?

Following the preassessment test, learning experiences need to be differentiated. Stronger students who have already achieved the learning goals of the upcoming unit as well as students lacking prerequisite content or skills need to be assigned modified or adapted unit goals in order to be appropriately challenged. However, the differentiation of learning goals inevitably raises the question of how these learning goals will be assessed. The question of differentiated assessment deserves a dissertation of its own.

In order to respect the traditional philosophy of evaluation underlying the Luxembourgish grading system, a balance needs to be found. Our Luxembourgish system expects every student to be evaluated in the same way. It is therefore unavoidable to establish a set of common goals which will be assessed according to the same evaluation criteria for all the students of a same class. In order to reach these goals, students are provided with differentiated assistance and allowed to work at their own pace. As academic standards should be seen as the “floor” and not the “ceiling” for learning goals, teachers might also go beyond and above these standards to add more depth or challenge to a unit in order to cater to their stronger students’ needs. However, these more challenging tasks cannot be part of the summative assessment.

Example:

All the students are required to complete Station 3 (see below) as it corresponds to the common learning goal that will be assessed in the summative test. Moreover, in order to foster student engagement, the learners are asked to complete at least 3 stations in class and finish them as their homework.

5. Developing instruction including areas for differentiation

At this stage, teachers consider how the unit will be best taught to respond to the students’ needs. Since differentiation is purposeful, it needs efficient planning tools. The aim of this point is not to mention all the possible instructional strategies. It rather focuses on a personal selection of strategies to differentiate EFL instruction in an EST class with only 3 English lessons a week. These strategies are tiered activities and learning stations.

Tiered activities

As mentioned above, “a good readiness match pushes the student a little beyond his or her comfort zone and then provides support in bridging the gap between the known and the unknown” (Tomlinson 2001, p.45). Creating tiered activities thus consists in

- thinking of a ladder ranging from very high to low skill and complexity of understanding,

- “cloning” a same activity along that ladder to provide different versions at different degrees of difficulty and

- matching a version of the task to each student based on student need and task requirements.

Learning stations

A method for managing multiple tiered tasks in the classroom is to assign students to stations. Not all students need to go to all stations nor do they need to spend the same amount of time at each of them. Concretely, teachers create tiered activities and place each activity in a separate station. Then, teachers assign students to the appropriate stations, or – even better – help the students choose what stations answer their learning needs. Stations need to be well-organised and respect the following principles (Heacox 2009; Hume 2009; Linser et al. 2009; Gregory & Chapman 2006);

- All the station activities must be focused on significant learning goals.

- Activities should range from an entry-level to more advanced skills and processes and yet engage all students in challenging learning.

- An activity must first have been modelled as a whole class activity. If students have never made a booklet before, do not put a booklet into a station until the class has been taught about it before.

- Activities can be completed alone, in pairs or small groups. Students must be informed about how they are to do the work.

- Explicit directions for how to complete the tasks should be provided at each station. Step-by-step procedures, models and/or samples should also be provided if needed.

- Students should be given a checklist to check on their work and progress as they move from one station to the other.

- Teachers may make a distinction between compulsory and optional stations.

- Teachers need to check on the work that has been done, e.g. by expecting the students to ask for permission to move on to the next station.

- Students should be sufficiently autonomous to be able to work on their own and keep themselves busy if they are finished quicker than planned (teachers are advised to prepare “sponge activities” to “sponge” up the extra time without wasting instructional time (e.g. crossword puzzles/word, online research, etc.).

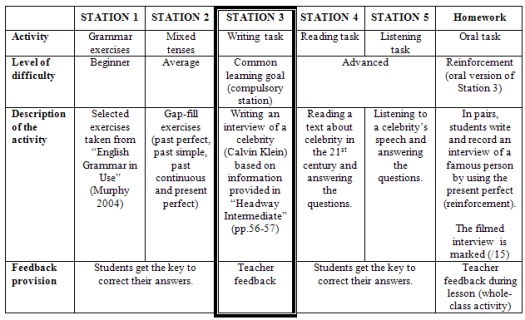

Example:

The students are given their correction of the preassesssment test and are asked to analyse their answers. Based on their results, they have to choose among five stations the one that best caters to their needs. As far as this sequence about the present perfect simple is concerned, the students are provided with five different stations. If the students complete the preassessment exercises that correspond to Station 1 successfully, they can directly start at Station 2 without completing Station 1. Otherwise, they need to deepen their understanding of this particular grammar point and/or ask for further teacher explanations at Station 1. As soon as the students are able to complete Station 3 (compulsory) successfully, they are given the opportunity to practise other skills through – in this case – reading and listening activities.

6. Whole-class sharing of experiences/outcomes

Students are given a certain amount of lessons to complete their stations and are asked to finish their work at home. The students’ productions should either be collected or shared in class in order to foster student accountability and efficiency. When handing in their completed stations, the students are given one more lesson in which they can mention problems they encountered when they completed their task on their own and/or share their outcomes.

Example:

In this particular sequence about the present perfect, the students were given the opportunity to ask their remaining questions and then watched each others’ filmed interviews and were asked to provide each other feedback.

7. Summative assessment

The students are assessed in order to show whether they have reached the learning goal or not (see 4.1 and 4.4).

Differentiation becomes easier as your skills improve and the students become used to it and become more autonomous. As far as my project is concerned, attention can be drawn to the following positive aspects:

- There were fewer cases of misbehaviour in the differentiated classroom than in the traditional classroom as all the students were appropriately challenged and thus more likely to stay on task. However, some students who lack maturity and autonomy still need to be particularly taken care of to prevent disciplinary problems.

- Student choice is a powerful strategy which makes students feel trusted and valued. Moreover, student choice leads students to become more self-aware and learn to make the right choices for themselves and be held accountable for the latter.

- Differentiation in my classroom helped particular students to make impressive progress. Two particularly weak students took advantage of the approach to work at their own level and catch up with the others so that their level of proficiency rose above some average students’, thus fostering their pride and self-confidence. Those two weak students achieved this through hard work in and outside the classroom, which some other weaker students did not do.

- Differentiation fosters students’ awareness and respect for differences.

- Differentiated instruction makes students acquire skills essential to their employability and career success, such as self-awareness and assertiveness, organisational skills, strong communicational skills, teamwork, decision-making and resourcefulness in the face of challenges.

Despite these advantages, a number of negative aspects could also be identified within the framework of this project:

- Although experience enables teachers to design and use templates to systematise their differentiated instruction, the latter remains time- and energy-consuming. Moreover, differentiation must be systematised and founded on disciplinary and interdisciplinary collaboration and teamwork to yield substantial and potentially long-lasting effects. If 7th–grade students got already introduced to the idea that they are different individuals with different needs who learn in different ways, and if teachers integrated differentiated instructional strategies in their teaching more regularly, differentiated instruction would become easier to implement.

- Lower teacher control in the differentiated classroom can lead some students who lack autonomy to follow the law of the least effort and eventually make no progress at all. In the framework of my project, fewer students than expected completed their three stations regularly. This made me question whether this was due to a lack of motivation, engagement, maturity and/or learner autonomy and if I shouldn’t have provided more guidance and control. Nevertheless, in my opinion, this lack of student efficiency cannot be attributed to differentiated instruction only. It must be said that, out of the 20 students, 8 failed at the end of the year because they had performed poorly in more than 4 subjects. One main criticism which could be made of this project is that it did not manage to motivate those students to work harder through appropriate challenges.

Questionnaires and discussions with my students revealed that the students’ lack of engagement, autonomy and/or motivation was due to the following points to bear in mind when differentiating for the first time:

- Students and teacher discover differentiated instruction simultaneously. When a new strategy is implemented in class, neither the students nor the teacher are able to anticipate the outcome and this trial-and-error process can make some students feel like guinea pigs. In other words, trying to take the students out of their comfort zone and to improve one’s own teaching practice at the same time can make some students feel insecure. In my case, this feeling grew into a feeling of mistrust for those students who were disappointed with their results in the summative assessments. The students had been told that differentiation would help them make continuous progress but all they got were bad marks. This ended up in a vicious circle where students’ insufficient work made them get bad marks, which, in turn, reduced their motivation to work. One student asked me at the end of year why I kept on trying to improve the stations despite the students’ lack of work. This question made me realise that most of my students were attributing their underperformance to my continuous attempts at differentiating instruction but did not question their own attitude towards work and especially homework.

- Second, I was the only teacher to differentiate instruction in their class. As the students realised that all their other teachers taught in a more traditional way and that my differentiated teaching needed improvement, they finally started to question the efficiency of my teaching and became less engaged. At the end of the year, the majority of the students expressed their willingness to leave the stations aside to be taught English in a more frontal way, just “like the other teachers do” all the more since English is a minor subject for which they think they should not be expected to work too hard.

- A third aspect highlighted by the students was the fact that differentiation always took the form of stations, which finally started to become monotonous. It is therefore good to bear in mind that even in the differentiated classroom, variety is essential to keep the students engaged.

Heacox points out that “the most critical variable in whether differentiation really happens is your will to make it happen” (2001, p.16). Although our will is crucial, it would not be honest to say that differentiating language instruction in the EST is easy and always successful. As a result, it is crucial to be well-aware of the potential hurdles that might be on our way towards differentiated instruction. Nevertheless, once those hurdles have been identified, all that remains is to get prepared to gain momentum and take the leap towards more equal opportunities for our students to make continuous progress in our schools.

Gregory, G.H. & Chapman, C.M. ed., (2006) Differentiated Instructional Strategies: One Size Doesn’t Fit All, 2nd ed., Corwin Press.

Heacox, D., (2001) Differentiating Instruction in the Regular Classroom: How to Reach and Teach All Learners, Grades 3-12, 1st ed., Free Spirit Publishing.

Heacox, D., (2009) Making Differentiation a Habit: How to Ensure Success in Academically Diverse Classrooms Book with CD-ROM, Free Spirit Publishing.

Hume, K., (2009) Comment pratiquer la pédagogie différenciée avec de jeunes adolescents ?: Differentiating for Success with the Young Adolescent, De Boeck.

Linser, H.J. & Paradies, L., (2001) Praxisbuch: Differenzieren im Unterricht, Cornelsen Verlag Scriptor.

Linser, H.J., Paradies, L. & Sorrentino, W., (2009) 99 Tipps: Differenzieren im Unterricht: Für die Sekundarstufe I, Cornelsen Verlag Scriptor.

Meirieu, P., (1995) Différencier, c’est possible et ça peut rapporter gros! Available at: http://scholar.googleusercontent.com [6th April, 2012].

Rey, B., (2007) Discipline en classe et autorité de l’enseignant: Eléments de réflexion et d’action, De Boeck.

Roberts, J.L. & Inman, T.F., (2008) Strategies for Differentiating Instruction: Best Practices for the Classroom 2nd ed., Prufrock Press, Inc.

Scharle, A. & Szabó, A., (2000) Learner autonomy: a guide to developing learner responsibility, Cambridge University Press.

Smith, C.M.M., (2006) Including the gifted and talented: making inclusion work for more gifted and able learners, Taylor & Francis.

Tomlinson, C.A., (1999) The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners 1st ed., Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development.

Tomlinson, C.A., (2001) How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms, ASCD.

Wiggins, G.P., (2005) Understanding by design, Upper Saddle River NJ: Prentice Hall.

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Building Positive Group Dynamics course at Pilgrims website.

|