The Graphic Novel as a Springboard

Christine Faber, Luxembourg

Christine Faber is a teacher at the Lycée Technique pour Professions de Santé in Luxembourg. E-mail: christine.faber@education.lu

Menu

Introduction

Theoretical framework

Comic project: from theory to practice

Project evaluation

Conclusion

Selected bibliography

The genre of comics, which promotes visual as well as literary and linguistic competences, forms the foundation of the interdisciplinary project that I implemented with my 3eE (arts section) at the Lycée Aline Mayrisch in Luxembourg. Comics and graphic novels merge images and text, thereby requiring readers to make use of wide array of strategies to decipher the often very complex narrative forms.

A primary aim of the project was to analyse in what way comics can be used to help students develop their reading, writing and analytical skills. The project allowed students to get acquainted with the specific narrative techniques of comics, and to compare these to the strategies used by writers of prose. The students then had the opportunity of writing their own short stories in groups and of transforming these into their own individual comics using the narrative strategies and techniques that they acquired in the first phases of the project.

The project, which was highly demanding in terms of creative output, was specifically tailored to the ‘E’ students’ interest in art. My ambition to stimulate the students’ motivation to learn and use English lead me to a project-based learning approach, which allowed the students to work on a specific project throughout a whole term with clear goals to achieve. Most of the lessons are based on cooperative learning methods, first and foremost group work.

Graphic novels and comics can offer meaningful and inspiring material in the English language classroom. To begin with, it may be useful to find a clear definition of the terms graphic novel and comic book. As Jacquelyn McTaggart explains in her essay ‘Graphic Novels – The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly’,

Today the term “comic book” describes any format that uses a combination of frames, words, and pictures to convey meaning and tell a story. (...) The lengthy [publications], referred to as graphic novels, are also comics. (...) Graphic novels are bound like traditional books and last longer than a comic book. (2008, p. 31)

Will Eisner, who needs to be regarded as one of the key figures and theorists of the genre, coined the term “sequential art” in 1985, an expression that is still widely used to refer to comics today (2008, p. xi). As the term aptly suggests, sequential art is a literary genre that deals with ‘juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence’ (McCloud, 1993, p. 9). It should be emphasised that the most striking characteristic of sequential art is the complex ‘interplay of words and images’ (Eisner, 2008, p. 2), which lies at the very heart of the genre. As Eisner explains, comic book artists have managed to create ‘a successful crossbreeding of illustration and prose’ (2008, p. 2), which continues to fascinate readers to this day. Although nowadays, comics and graphic novels are increasingly recognised as a rich resource for activities inside the language or art classroom, it is important to understand that this was not always the case. Indeed, as Rocco Versaci rightly points out in his essay ‘“Literary Literacy” and the Role of the Comic Book’, ‘for most of their history, despite – or perhaps because of – periods of popularity, comic books have been denigrated as sub-literate trash’ (2008, p. 94). Until quite recently, comic books were often perceived to be a lower form of literature having little more to offer than entertainment value. Considering that comics consist to a large extent of visual images, it was widely feared that the genre would ‘dumb down’ its readers due to insufficient intellectual challenge. The assumption was that reading pictures is, after all, much easier than reading text.

Several theorists, first and foremost Scott McCloud, have managed to turn this perception upside down and shed light on the great complexity and pedagogical value of the genre of comics. In his pivotal book Understanding Comics – which, like its successor Making Comics, brilliantly presents the theory of comics in the visual form of a comic – McCloud dissects the complex narrative strategies of comics as a genre which blends both pictorial and textual information. As a reader, we learn about the various kinds of transitions between panels, the importance of panel arrangements to create a particular flow on a page, the distinct art of comic drawing and the possible combinations of word and image. By studying the intricate composition of a comic and focusing on the narrative strategies that the comic artist has employed, students can learn a great deal about techniques of storytelling in general. Indeed, comics can be a fantastic tool to draw students’ attention to the importance of characterisation, plot, setting and other narrative devices needed to successfully tell a story.

Sequential art has, in effect, completely redefined what the act of reading actually encompasses. Eisner rightly suggests that reading a comic exercises ‘both visual and verbal interpretative skills (...); [it is] an act of both aesthetic perception and intellectual pursuit’ (2008, p. 2). As such, one could claim that comics and graphic novels offer a much more intense challenge to their readers than purely textual literature ever can.

Amongst the wide range of literacies that are trained in the act of reading and analysing sequential art, visual literacy seems particularly important. Versaci rightly notes that ‘for our students, literacy does not simply involve the written word’ (2008, p. 96). Indeed, we should not forget that the generation of students we are teaching today is used to reading images 24/7, be it in advertising, on the internet, on TV or at the cinema. Images are, today more than ever, ubiquitous and have become the primary tool to convey meaning. As Versaci goes on to explain,

If part of our job as English teachers is to make our students life-long readers who are astute and eager interpreters of the world around them – and I believe it is – then we need to address our students’ visual literacy.’

(2008, p. 96)

This new generation’s shift towards a predominantly visual intelligence needs to be reflected not only in how we teach – for instance, offering visual input and information as often as possible – but also what we teach. In fact, sequential art can guarantee an adequate practice of these visual competences like no other literary genre can. It should also be mentioned that our students today have a remarkable ease of reading and understanding the often very complex language of comics. Versaci explains these new reading skills as follows:

(...) the act of reading a comic cuts much more close to how our students today receive information. I’m thinking particularly of the Internet, where the sites that I see my students visiting regularly are densely packed and ask readers to move their eyes diagonally and up and down in addition to side by side – the same kind of movements that come with reading comic book panels and pages. (2008, p. 97)

Considering this generation’s predisposition towards visual input, comics and graphic novels should be recognised to be a useful resource to awaken the students’ interest in literature, to foster their reading and analytical skills and to educate them about narrative strategies and storytelling techniques.

Content-based and project-based learning

The language classroom today offers students the possibility of acquiring the target language in new stimulating ways that allow authentic learning to take place. Content-based and project-based instruction are two examples of a growing set of methodology at the language teacher’s disposal, which enable learners to strengthen their language abilities by focusing on non-linguistic subject matter.

H. Douglas Brown defines content-based learning (CBL) as a learning approach in which ‘language becomes the medium to convey informational content of interest and relevance to the learner. Language takes on its appropriate role as vehicle for accomplishing a set of content goals’ (2007, p. 55). This learning method has multiple benefits: firstly, CBL shifts the focal point away from linguistic features to meaning. It thus contrasts considerably with the traditional (second) language curriculum, where language competences are primarily developed by focusing on the target language itself. The students get the chance to increase their knowledge in hitherto unexplored domains while at the same time practicing their speaking, writing and comprehension skills in the target language. As Nik Peachey from the British Council explains, ‘this is thought to be a more natural way of developing language ability and one that corresponds more to the way we originally learn our first language ’(Peachey, British Council, 2003). Secondly, CBL can be highly motivating for students. Brown notes that CBL can help students become aware of ‘their own competence and autonomy as intelligent individuals capable of actually doing something with their new language’ (2007, p. 56). This can boost the learners’ confidence and increase their intrinsic motivation for learning the language.

Finally, CBL also offers a welcome challenge to teachers, who need to become what Brown calls ‘double experts’ (2007, p. 56). Indeed, teachers can thus widen their perspective by exposing themselves in-depth to a subject matter other than their specialty, which is the second language.

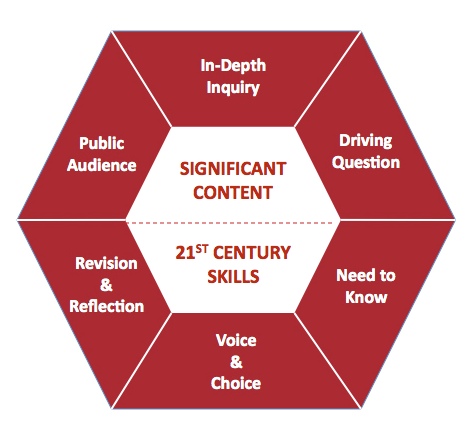

In project-based learning (PBL), the students do an in-depth inquiry about an authentic and motivating topic over a set period of time. The project revolves around a particular challenge or problem, which the students need to tackle together by using cooperative skills and by working autonomously.

source: www.bie.org/about/what_is_pbl

As the diagram proposed by the Buck Institute for Education (BIE) aptly shows, a primary condition for a successful implementation of PBL is that the subject matter of the project has significance for the learners, i.e., the learners need to recognise its value and be interested in it. According to the BIE, the students also need to have ‘a clear vision of an end product’ (Buck Institute for Education) right from the start of the project. Giving the students a clear goal to achieve ‘creates a context and reason to learn and understand the information and concepts’ (Buck Institute for Education) that the students will acquire in the course of the project. Furthermore, this final product should also be presented in one form or another to the public, as a way of ‘increasing students’ motivation to do high-quality work, and [adding] to the authenticity of the project’ (Buck Institute for Education). Yet although the outcome of the project is certainly important, PBL is first and foremost focused on the process of reaching these final objectives.

Last but not least, it should be emphasised that PBL very much relies on cooperative learning methods such as group work. Herbert Gudjons even refers to a “general indispensability of cooperation” in project-based learning situations, which help the students to learn “from and with one another” (2001, p. 87). The ability to communicate and cooperate belongs to what the BIE refers to as ‘21st century skills’ in the diagram depicted above, as these skills have become increasingly important in today’s globalised and connected world.

Group work

The comic project not only aimed to foster the students’ writing and reading skills but also to offer the students the chance to experience a shared sense of achievement by working in groups with their peers. Whilst traditionally, schools tend to encourage individualistic and competitive learning strategies, there has been a considerable shift towards cooperative and collaborative learning methods in the past years (Johnson and Johnson, 2004, p. 188). This new tendency can be explained by the numerous benefits that group work has proven to have for the students’ learning process, overall achievement and psychological health (Johnson and Johnson, 2004, p. 188). First and foremost, group work allows students to help one another to achieve their shared learning objectives. As Atkinson and Raynor rightly note, ‘achievement is a ‘we’ thing, not a ‘me’ thing, always the product of many heads and hands’ (1974). Indeed, it is much easier and more rewarding for students to work on a particular task cooperatively with their peers than doing so on their own. Mixed ability groups, for instance, allow weaker students to work together with stronger students who can support and guide them in their learning process. In their publication Assessing Students in Groups, David and Roger Johnson demonstrate that ‘cooperation tends to promote higher achievement than competitive or individual efforts’ (2004, p. 34) and that students working in cooperative groups ‘tend to be more involved in activities (...) and attach greater importance to success’ (2004, p. 188). In fact, the effects of group work on students’ behaviour and their overall learning attitude can be quite remarkable: indeed, research has confirmed that cooperative learning increases intrinsic motivation and dramatically improves students’ willingness and effort to achieve set goals (2004, p. 34). Johnson and Johnson emphasise that group work can be especially useful in tasks where ‘new and complex knowledge and skills need to be mastered or extraordinary effort is needed’ (2004, p. 8). Perhaps most importantly, they also assert that groups can ‘ferment creativity and the unlocking of potential’ (2004, p. 9). This struck me as a particularly appealing benefit of group work when I started setting up the comic project. As my project description will show, the task that my students completed in groups was highly demanding in terms of creative input, and I felt it was important that the students could join efforts in the creative writing production phase.

Comic project: from theory to practice

Having set the theoretical groundwork of this project, it is now time to take a closer look at the various phases of the project itself.

Project description and objectives

Part 1: Theory

As preparation for the first part of the project, I asked the students to read Robert Louis Stevenson’s novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde over the Easter holidays. They received a worksheet to guide their reading of the story and to help them become more aware of Stevenson’s characterization techniques. The students were asked to take notes of key descriptions of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’s personality and physical appearance. This task was meant to draw the students’ attention to the striking contrasts that Stevenson created between the two characters, which slowly begin to dissolve as the story progresses. As a way of fostering the students’ ability to visualise characters in a story, I asked them to paint or draw their vision of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. This attempt to illustrate the duality of the two main characters in the story was important for the project as a whole; indeed, it encouraged students to read closely for key descriptions of Jekyll and Hyde’s personalities and looks in order to translate this textual information into visual imagery. Straight after the Easter break, the students were thus able to present their illustration to the class and compare their vision of Jekyll’s double personality with those of their classmates. In order to check whether the students did their homework of reading the story over the holidays, the class did a small multiple-choice quiz at the beginning of project.

The first two lessons dedicated to the project first and foremost aimed to offer an overview of the novella and an introduction to some key narrative techniques. By focusing on selected scenes in the novella, we were able to analyse and discuss Stevenson’s use of narrative devices – such as characterisation, imagery and point of view – in context. In order to offer the students clear definitions of these concepts, which they could refer back to later on in the project, I distributed a handout with brief theoretical definitions to the students. I was fully aware that Stevenson’s novella presented a challenge to the students in terms of language and concepts, and therefore I felt it was important to talk about the plot in detail to assure full comprehension before we could move on to a more in-depth analysis of important themes in the novella. For many of my students, reading a classic in English was a new experience, and some of them told me that they felt intimidated by the idea of reading classic literature. This was confirmed by the questionnaire the students filled out at the beginning of the project: indeed, only four of the seventeen students claimed to be interested in reading classics, mostly due to the difficult language in literary novels. This result startled me and convinced me of the urgency of including classic literature in the project as well. As a way of facilitating access to classic literature, I chose to focus on selected scenes of the graphic novel Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (which the students received as handouts) alongside the original version by Stevenson. In the fourth and fifth lesson of the project, the students thus divided up into four groups and received a worksheet with questions about a particular scene in the novel and graphic novel. The students were asked to contrast and compare both versions, and take notes of their observations. The main objective of this double-lesson was to foster the students’ reading and analytical skills as well as to offer them an introduction of the genre of the graphic novel. The tasks in these lessons required an ability to read closely – both text and images – and an awareness of the narrative strategies we talked about before (especially imagery and characterisation).

The lessons dealing with the graphic novel Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde allowed the students to discover inductively some of the key principles and narrative techniques of the genre of sequential art. Indeed, by focusing on the way that the comic tells the story as opposed to the novella, the students became aware of strategies a comic artist can use to create atmosphere in a panel (setting, imagery) or to highlight particular personality traits of a character (characterisation). These two lessons lay the groundwork for the theoretical lessons about sequential art, which were scheduled as a next step. Scott McCloud’s publications Understanding Comics and Making Comics, which, as I already stressed in Chapter 2, are milestones in the theory of sequential art, were the main source of information for the comic theory lessons. I meticulously composed a ‘Making Comics’ booklet for the class summarising the most important aspects of the genre of comics. Particular focus was laid on the various kinds of panel transitions as well as the different ways in which words and images can be combined in a comic. For both of these focal points, I devised activities, which the students completed in pairs or in groups, to put the theory into practice. By the end of these lessons, I wanted the students to be able to comprehend the narrative techniques of comics and use the specific lexis of comic theory.

These theoretical lessons marked the end of the first part of the project and prepared the ground for the more active production phase. I should mention here that The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde not only offered me the opportunity to highlight the distinction of storytelling techniques of prose as opposed to comics, but it also allowed us to explore a theme which would form the basis of the entire project: the double. Indeed, the concept of duality and of the double life is one of the key elements in Stevenson’s story and offers endless possibilities of exploration. I decided to use this theme, which we discussed in great detail in the third lesson of the project, as a red thread that would run throughout the entire project.

Part 2: Production

In the first lesson of the production phase of the project, the students were told that they were going to write short stories of about 400-600 words in groups of 4 (and one group of 5), which offered a modern interpretation of the ‘double-life’ concept that we discussed in the context of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. With some guidance, the students were able to come up with examples of people living a double life in our society today, thereby realising that the theme of ‘the double’, which Stevenson focused on in his story, is still very much relevant in the 21st century. The class suggested a wide range of examples, from people who have affairs in their marriages and murderers who pretend to live a normal life in society to classic superhero stories (such as the Clark Kent/Superman dichotomy) and secret agents. The students received a worksheet including the organization of the individual groups, clear instructions and tips for the short story they should write and explanations about the alternating roles (chair, notetaker, timekeeper) they should allocate in their groups. Once the students had assembled in their respective groups, they began discussing the theme and decided what kind of ‘double-life’ scenario they wanted to base their story on.

In the first two lessons, the groups had to come up with a precise plot and develop the characters in their stories. As a next step, they had to write a first draft of their story, before editing it and handing it in. In total, the class had four weeks to finish up their short stories at home and at school. During this month, the students were given five English lessons to work on the stories in class and consult me when necessary. The narrative techniques of prose, which we analysed in the context of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, provided an important foundation for the students’ writing. Indeed, the students were asked to pay particular attention to their characterisation technique and to create a story that the reader could easily visualise.

Once they had handed the stories in, I corrected and evaluated their texts which they would now transform into their very own comics. The production phase of the comics took up a total of eight graphic design lessons and had a duration of four weeks. Whereas the short stories were written collaboratively in groups of four or five, I decided to let each student create his/her individual comic about the story he/she wrote in class. Producing a comic is a personal endeavour and I wanted each student to be able to express his/her vision of the story in his/her own style. Another aim was to show the students that when we read, we all picture the story differently; reading is an act that happens inside every person’s imagination. The end result of the project would demonstrate this idea forcefully, as the four or five comics created about the same story differed greatly from one another.

During the graphic design lessons, the students' art teacher helped them to translate the story from text to visual imagery and offered them advice in terms of composition and technique. I also decided to sit in in these lessons to encourage and remind the class to make use of their knowledge of comic theory in the production of their own comics. Each panel had to fulfill a particular function to progress the story and thus had to be chosen with great care. The students also had to think about the connection of the image to the text included in the panels, as well as the transitions between the different panels. During these lessons, the students also had the chance to get some inspiration and analyse the techniques of some comic masters by browsing through a large variety of graphic novels and comic. The class also received the exact guidelines for the comic beforehand: the comics should be spread out on two A3 pages, drawn in black and white with no more than 16 panels in total. By limiting the panels to eight per page, the students were forced to strip the story down to its most essential moments and tell the story with only a few carefully selected images and text elements. This allowed students to develop their ability to summarise a story effectively and to focus their attention on a manageable body of work.

Part 3: Presentations

The last phase of the project consisted of student presentations about their work. Each group started by summarising its story to the class and explaining the story’s rationale in relation to the theme of ‘the double’. Next, every student talked about his/her comic adaptation of the story. I asked the students beforehand to select a few panels and analyse these in detail in the presentation, paying special attention to the word/image connection and the transitions between these panels. Finally, the presentation was also an opportunity for the students to talk about their own experience of the project: did they enjoy working in groups? What was their biggest challenge in the project? Although the students got the chance to give more detailed feedback in an evaluation form, this oral feedback was also valuable because it offered the students and me the opportunity of discussing the project together.

The final productions – both the short stories and the comics – were exhibited in the school foyer in the last week of school, and were printed as a comic booklet to offer the students and the Lycée Aline Mayrisch a tangible trace of the project. As a further step to share the project with the school community, the four best comics (selected by the graphic design teacher and me) were also featured in the ‘Periskop’, the school’s quarterly paper.

Writing and reading skills

As already mentioned in the introduction, a main objective of the comic project was to foster the students’ writing skills and their competences to read both image and text (sometimes simultaneously). For many of my students, this was their first creative writing experience in English class. Therefore, I deemed it important to provide them with the necessary understanding of narrative techniques in advance, which they could then explore first-hand when writing their own short story. The checklist and the ‘short story tips’ that I provided the students with to offer them an additional help in their writing process were, in my opinion, vital to draw their attention to key issues to consider when writing their story. Whilst I noticed that several students consciously made use of the checklist during their group work sessions, others clearly preferred to work without such guidance and to simply dive into the writing phase. What I considered to be important was to give the students the option of using this checklist, without presenting these short story tips as a mandatory aspect of the writing phase. Above all, I wanted the students to have fun inventing a story and bringing characters to life. Indeed, my priority in teaching writing skills was to give the students an appetite for creative writing in general, and to help them understand which narrative tools writers can use to create a powerful story with intriguing characters. In the first lesson of the writing sequence, I was pleased to notice that most students were eager to share their ideas for their story with their peers, and that they did not feel intimidated by the blank page. Indeed, most groups quickly began writing the first draft of their story, adding ideas along the way. I should add here, that I quickly became aware that the initially imposed word limit of 400-600 words was insufficient, and I therefore decided to increase the limit to 750 words.

If I had had more time at my disposal for the project as whole, I would have explored the writing process in greater depth. One could, for instance, have used a portfolio system to make the students assemble their various drafts and to show the evolution of the writing style. In fact, I believe that I should have marked the initial draft of their story that they handed in as well as the final version where they could incorporate my corrections and suggestions. This would have allowed me to put more emphasis on process as opposed to product, which would have also been more in line with the project-based learning approach that I implemented.

During the writing process, I consciously decided to stay on the sidelines, adopting what Brown calls the ‘facilitative role of the writing teacher’ (2007, p. 396). Brown advises teachers to ‘offer guidance in helping students to engage in the thinking process of composing but, in a spirit of respect for student opinion, [not to] impose his or her own thoughts on student writing’ (2007, p. 396). Once I provided the students with the corrected version of their stories, I considered my intervention into their written production to be completed. In retrospect, I believe that I should have checked the adapted quotes and abstracts from the short story that the students incorporated into their comics as well, as I noticed later on that some comics included grammatical mistakes.

To what extent, then, did our analysis of narrative techniques in prose and the short story writing impact the students’ writing skills?

Even though the submitted stories were certainly not error-free and occasionally included some rather awkward expressions and sentence structures, I must say that I had never seen my students being so focused on their writing style. Monitoring the group work sessions of the short story writing, I repeatedly witnessed students discussing stylistic options and making suggestions to improve the overall effect of the story. Personally, my goal has thereby been achieved: the project has encouraged the students to write more consciously bearing important narrative techniques of prose in mind.

The final auto-evaluation revealed that a striking 13 out of 17 students believed that the project has helped them improve their writing skills. It is my hope that this experience of writing their own short story has encouraged some of my students to possibly explore creative writing further in the future.

It is important to note that fostering the students’ writing skills relied directly on the project’s previous focus on reading skills. It was only by paying close attention to the narrative techniques of prose, which we explored in the context of Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, that the students could incorporate some of these concepts in their own writing. As my introduction and project description have already pointed out, developing the students’ reading skills – of texts as well as of images – was a primary goal of the project. By allowing the class to contrast and compare the novella and the graphic novel of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, the students learned that the act of reading can take many forms and that images and words are equally powerful tools to convey a story effectively. This comparison further revealed that it is possible to read and understand a story with only a few carefully crafted images complemented by text. Many of the students mentioned that although the graphic novel clearly left some details out, the reader still managed to understand the story and get a sense of the atmosphere by looking at the interplay of text and image in the graphic novel. Observing my students’ growing awareness of the various reading strategies and their impressive visual literacy was one of the most interesting elements of the project for me.

Ideally, I imagined that the project would trigger a curiosity in my students to read classics or/and graphic novels. Following the initial questionnaire, which exposed that a clear minority of the students were interested in reading classic literature, I was delighted to find out that at the end of the project, 9 out of 17 students claimed that the project sparked their interest in classics. If the project managed to encourage more than half of the class to read classics in the future, I am happy with what I achieved in terms of decreasing their apprehension of reading classic literature. I was aware that I would most likely not be able to awaken a genuine interest in literature in all of my students, and I should say that that was not really my objective.

Similarly, their interest in comics was also exceptionally high when they finished the project: 16 out of 17 students stated that they would read comics or graphic novels in the future. Crucially, however, the comic theory that they encountered in the project has equipped them with the necessary knowledge to access the unique language of comics and read panels more intelligently. As student P. noted: ‘I certainly won’t read a comic again without looking at the transitions and the different kinds of styles.’

Creative skills

Perhaps one of the most unusual aspects of this project devised for English class was how highly demanding it was in terms of creative input. Indeed, several components of the project required students to explore their imagination and make use of their creative skills. As I designed the project, I felt rather confident that this class would be up to the challenge, considering that they all chose the arts as their focal point for the final three years of secondary school. The Jekyll and Hyde drawings, which kick-started the project, already demonstrated that the students were able to visualise the textual descriptions of the characters in Stevenson’s novella, grasp the duality of the characters and translate them into imagery. Reading a story creates an imaginary world in our minds; the activity of drawing the characters as one pictures them in one’s mind is by all means not an easy task. Yet it is important as a way of making the abstract characters in the story tangible. This first creative task thus functioned as a bridge between text and image. Some of the results were impressive in that they clearly showed the split personality of Jekyll, and visually played with the good/evil dichotomy. Personally, I considered the students’ inventive and original illustrations to be a promising start for the project.

The creative writing process was equally challenging for the students. Instead of making them recycle other people’s ideas, I wanted my students to recognise their own creative potential and use their imagination to come up with their very own story dealing with the theme of ‘the double’. As we have seen, this creative process was devised as collaborative effort. Having no previous experience of creative writing in English, writing the stories individually may have been daunting for some students. As one of my students claimed, ‘Personally, writing a story on my own would have been disastrous. Thankfully, we could help each other in order to put a great story on paper.’

In terms of creative input, there is no doubt that the comic adaptations were the most time-consuming and demanding element of the project. In fact, this task tied in directly with the Jekyll and Hyde drawings at the beginning: in both tasks, the students had to translate text into image. Looking back, I believe that telling the students to use precisely 16 panels (i.e. 8 panels per page) was too limiting. With a task such as this, it is necessary to leave the students a maximum amount of flexibility for expression; some students may have been able to tell the story efficiently with only 16 panels, yet others may have needed 4 more panels. Therefore, if I were to redo the project, I would tell the students that they have between 16 and 20 panels at their disposal.

Much of the positive feedback in the final evaluation form revolved around the comic theory and production. As F. explained, ‘the thing I enjoyed most was to draw the comic, do research on how to draw specific objects and places, and the thinking process involved in finding the right perspective and image.’ Another student, N., noted: ‘I enjoyed thinking about every character, every panel and every scene. It was interesting to see how much work it is but at the end you can be really proud of the result.’ Seeing the students’ final productions and listening to them present their work to the class, I believe that I succeeded in familiarising them with the genre of sequential art and showing them the infinite creative possibilities of the genre.

Group-work

Considering that a significant part of the comic project was founded upon collaborative working methods, it is necessary to assess how successful these group work sessions actually were. I am satisfied with my choice of dividing the students up into groups myself, as this allowed me to compose teams of students with varying abilities. The stronger students could thus help out the less-able students to achieve their common objectives. I believe that the group work sessions were especially valuable to develop the students’ interpersonal skills. I noticed that the teams began to bond in these sessions, and that the students genuinely enjoyed collaborating with their peers. The results of the evaluation form clearly confirmed this impression: 16 out of 17 students stated that they liked working in groups. Whilst M. noted that the group work was valuable because the students ‘learn to stick together’, N. said that ‘it was fun to imagine a story with them’. C., one of the students who struggled the most in English class, explained that she liked ‘working in groups, because it was an opportunity for us to share our ideas. The presentations were good too, because we could see and also share what we created over the weeks.’ Only one of the students, E., complained that she felt she did most of the writing in her group. To avoid such feelings of frustrations, it may be useful to monitor the groups even more closely and to use Johnson and Johnson’s suggestion of asking the students to keep ‘group folders, in which they record each member’s work and contributions to the project’ (2004, p. 97). Judging from my own observations, however, I believe that all of the students felt the necessary level of individual and group accountability.

Overall

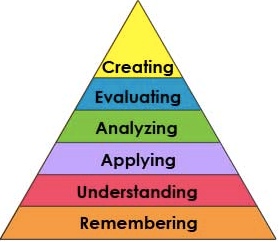

In fact, the structure of the project roughly follows the pyramid shape of (the revised version of) Bloom’s taxonomy. The pyramid offers an overview of the various intellectual levels of learning behaviour.

source: ww2.odu.edu/educ/roverbau/Bloom/blooms_taxonomy.htm

The quiz at the very beginning of the project corresponds to Bloom’s category of ‘remembering’: the students simply had to recall the plot of the novella and demonstrate that they read the story carefully. The ‘understanding’ level of the pyramid may help us to describe the project’s focus on narrative techniques of prose and the comic theory lessons. Indeed, these lessons aimed to help the students understand these concepts and prepare them for the following phase. This next stage – the ‘applying’ and ‘analysing’ level – required the students to compare the narrative strategies of prose and sequential art and to put the comic theory they encountered before into practice (by analysing, for instance, various panel transitions). The project thus gradually moved towards higher thinking skills, with the final category – ‘creating’ – taking the lead role in the story writing process and the comic production phase. Bloom’s taxonomy may thus be a useful tool to understand the connections between the multiple phases of the comic project.

To conclude my assessment, I would like to briefly discuss the interdisciplinary component of the project. In view of the students’ comments and appraisals in the final questionnaire, I feel certain that they appreciated the interdisciplinary angle of the project. F., one of the strongest students in class, noted that ‘it gave the project a real continuity’. P. explained: ‘I think it was good to be marked in both classes seeing as, in my opinion, they were co-dependent.’ In fact, 16 out of 17 students answered ‘yes’ to the question whether they liked that the project took place in English as well as art class. N. stated that ‘the comic needed theory and practice to be [combined], so it was really helpful to see the theory in English class and to work on it in art class’. E. added that ‘it was a different and new approach.’

Personally, crossing the limits of my subject and collaborating with a colleague from another discipline has been one of the most rewarding teaching experiences I have had up to date. I believe that students can gain great insight by approaching a topic from various perspectives. Much of the content we teach our students in different subjects could be easily connected to help the students see that many ideas, topics and concepts of various disciplines overlap. In fact, an interdisciplinary teaching approach prepares the students much more efficiently to what will expect them in the real world after secondary school. No matter which professional direction they choose to take, I have no doubt that our students will be challenged regularly to transgress their area of expertise and familiarise themselves with new ideas and subjects. An interdisciplinary approach to learning is, in my opinion, an important element of successful instruction which will, hopefully, play an increasingly important role in our schools.

The comic project was a highly diverse and challenging project, aimed to develop the students writing and reading skills as well as to increase their motivation in English class. Looking back on the project as a whole, I must say that the experience exceeded my (already quite high) expectations. Watching the students present their work in the final oral presentations was a full circle moment for me. As I listened to the descriptions and analysis of their comics, I could see how proud they were of the work they have achieved, within their teams as well as about their individual creative output. It proved to me how valuable project-based learning is for the students, as it allows them to have an authentic, tangible learning experience.

Of course, not every aspect of the project was flawless. Perhaps the most important change that I would carry out in any future reenactments of the project is to plan in more time for the comic productions, in order to prevent any last-minute stress and the risk of a decrease in motivation. I also believe that it would be possible to explore a similar comic project with a class other than an E section. Indeed, I believe the genre of graphic novels appeals to teenagers in general, also those who do not have a particular interest in the arts. Furthermore, comics and graphic novels could also function as a transition to classic literature by letting the students read the graphic novel of a particular story before they read the original novel. Whilst my project revolved around the topic of ‘the double’, teachers can draw from an endless list of other possible subjects to foster the students’ interest in sequential art.

Primary sources

Stevenson, Robert Louis, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and Other Tales, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006

Klimowsky, Andrzej and Schejbal, Danusia, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde: a Graphic Novel, SelfMadeHero, London, 2009

Secondary sources

Atkinson, John William and Raynor, Joel, Motivation and achievement, Winston, Washington DC, 1974, quoted in Johnson and Johnson, Assessing Students in Groups, Corwin Press, Thousand Oaks/California, 2004

Brown, Douglas H.,Teaching by Principles: an Interactive Approach to Language Pedagogy, 3rd edition, Pearson, New York, 2007

Eisner, Will, Comics and Sequential Art, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 2008

Gudjons, Herbert, Handlungsorientiert lehren und lernen, Verlag Julius Klinkhardt, Bad Heilbrunn, 2001

Johnson, David and Johnson, Roger, Assessing Students in Groups, Corwin Press, Thousand Oaks/California, 2004

McCloud, Scott, Making Comics, HarperCollins, New York, 2006

McCloud, Scott, Understanding Comics, HarperPerennial, New York, 1993

McTaggart, Jacquelyn, ‘Graphic Novels – The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly’ in Frey, Nancy and Fisher, Douglas (eds.), Teaching Visual Literacy, Corwin Press, Thousand Oaks, 2008

Versaci, Rocco, ‘ “Literary Literacy” and the Role of the Comic Book’ in Frey and Fisher (eds.), Teaching Visual Literacy, Corwin Press, Thousand Oaks, 2008

Websites

Buck Institute for Education, www.bie.org/about/what_is_pbl (last accessed 9th August 2012)

Peachey, Nik, 'Content-based-instruction', The British Council, 2003,

www.teachingenglish.org.uk/articles/content-based-instruction (last accessed 10th August 2012)

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|