A Comparative Study of Two Feedback Methods on Iranian EFL Learners’ Question Formation

Mahshad Tasnimi, Iran

Mahshad Tasnimi, PhD, is an assistant professor of TEFL at the English department of Islamic Azad University, Tehran North Branch, Iran. She is interested in second language acquisition, language teaching methodology and testing. E-mail: mtasnimi@yahoo.com

Menu

Introduction

Current approaches to form-focused instruction

The role of negotiation in corrective feedback

Method

Participants

Instrumentation

Procedure

Results and discussion

Conclusion

References

Appendix A

Appendix B

Providing students with feedback has been always a matter of debate in second language acquisition. The value of grammar teaching was downplayed by some scholars (Truscott, 1996, 1998) and it was claimed “language should be acquired through natural exposure, not learned through formal instruction” (Nassaji & Fotos, 2004, p. 127).

However, recent research has demonstrated that learners do not achieve very high levels of linguistic competence from entirely meaning-focused instruction, which is wholly concerned with communication of meaning, and no attention is given to the forms. Therefore, this route to linguistic knowledge is of limited value, except for beginners (Ellis, 1990, 2002). In this regard, Nassaji and Fotos (2007) assert that classroom based research has found convincing evidence that “instruction including some kind of FFI [form-focused instruction] is more effective than instruction that focuses only on meaning” (p. 11).

Current research in SLA has led to a reconsideration of the role of grammar due to four reasons. First, Nassaji and Fotos draw on Schmidt’s (1990, 2001) hypothesis that noticing is a necessary condition for language learning. They put that most SLA investigators agree that language cannot be learned without some degree of consciousness and that noticing plays an important role in L2 learning. Second, according to Pienemann’s (1989; 2007) teachability hypothesis which suggest that developmental features are fixed and can not be changed by instruction, while variational features benefit from instruction any time, it is possible to influence sequence of development through instruction if teaching coincides with the learners’ level of development. Third, inadequacies of communicative methodology where the focus is primarily on meaning-focused communication and grammar is not addressed renewed interest in grammar instruction. The evidence found in support of positive effects of grammar instruction is the forth reason. A well referred study by Norris and Ortega (2000) confirmed the effectiveness of L2 instruction by the results of a meta analysis of 49 FFI studies. The researchers concluded that FFI produces gain of the target structure, and that explicit types of instruction are more effective than implicit types. Furthermore, the effectiveness of L2 instruction is found durable (Nassaji & Fotos, 2004). Generally, “current research indicates that learners need opportunities to both encounter and produce structures which have been introduced either explicitly, through a grammar lesson, or implicitly, through frequent exposure” (Nassaji & Fotos, 2004, p.130). In this regard, a number of researchers have proposed various FFI classifications. One of the first and widely cited one is Long’s distinction between focus on form (FOF) and focus on forms (FOFS). Focus on forms is based on traditional approaches to language teaching in which linguistic forms are isolated and decontextualized in order to be taught or tested one at a time. On the other hand, focus on form follows a task-based syllabus in which learners’ attention is drawn to grammatical forms in the context of communication. There is a change between a focus on meaning and a focus on form (Ellis 1994; Nassaji & Fotos, 2004, 2007). Long believes that FOF is learner centered and occurs when needed, while FOFS is not needs-based and often results in boring lessons (Nassaji & Fotos, 2007). As far as FOF is concerned, it is mainly viewed as reactive responses to communication problems.

Ellis (2002) states that reactive FOF “involves the treatment of learner errors” (p. 423). To put it another way, it involves the teacher’s reaction to a problem in the course of communication. A good classification of reactive FOF is presented by Lyster and Ranta (1997) and Lyster (2004). What follows is a summary of their taxonomy:

Explicit feedback: explicit provision of the correct form

Racasts: reformulation of the learner’s utterance and providing learners with correct forms. (This is an implicit feedback.)

Prompts: indicating that the learner’s utterance is not correct, but not providing learners with the correct form. Prompts are of four types:

Clarification requests: implicitly indicating to the learner that a repetition or reformulation is required (e.g., Pardon me?)

Metalinguistic feedback: implicitly indicating to the learner that there is an error (e.g., Can you find your error?)

Elicitation: directly eliciting the correct form from the learner (e.g., How do you say X in English?)

Repetition: repeating the learner’s erroneous utterance especially by rising intonation

According to Ellis (2002), “reactive focus on form can be more or less implicit/explicit” (p. 426). Ellis states that explicit correction has the advantage of directing students’ attention to the correct form. However, it has the disadvantage of “turning a communicative task into a language-getting activity” (p. 426). Ellis asserts that explicit feedback can be performed in a number of ways. The simplest one is signaling an error directly. Another is using metalanguage to indicate what is wrong with an utterance (e.g., Tense). Another option is providing a correction and then providing opportunity for the student to practice. Using metalinguistic explanation of the correct form is another way of giving explicit feedback. Commenting on where to use explicit or implicit correction, Ellis (2002) puts the following:

If they [teachers] think that the student already knows what the correct form is and is capable of identifying the error for him/herself they may opt for a very implicit form of feedback (e.g. a recast) but if they think that the student does not know the form or will have difficulty in identifying what the error is they are more likely to choose an explicit form of feedback (e.g. a metalingual explanation). (p. 426)

N, Ellis (2007) draws on research in implicit and explicit learning and put that when material to be learnt is simple, learners benefit from explicit instruction. In contrast, when material is complex, implicit instruction is more effective.

In keeping with interests in focus on form, the role of negotiation has addressed much theoretical and empirical attention (Nassaji & Fotos, 2004; Lyster & Ranta, 1997; Lyster & Mori, 2006; Mackey, 11999; Tsang, 2004; Van den Branden, 1997). Defining negotiation as “the back and forth interactional strategies used to reach a solution to a problem in the course of communication” (p. 119), Nassaji (2007) states that the importance of negotiation in learning process originates from the vygotskian sociocultural theories of L2 learning which put particular emphasis on the role of student-teacher interaction. In the sociocultural view, language learning fundamentally is a mediated process and one whish is “dependent on face-to-face interaction and shared processes, such as joint problem solving and discussions” (Mitchell & Myles, 2004, p. 195). Asserting that the dialogic characteristics of negotiated feedback provide opportunities for scaffolding, Nasssaji (2007) puts that learners have opportunities to find out and self-correct their own errors during negotiation. Considering the role of negotiation of form, Lyster (2001) states that it provides learners with opportunities to make important form-function links in the target language without interrupting the flow of communication. Furthermore, he puts that negotiation of form might benefit L2 learning in at least two ways:

(a) by providing opportunities for learners to proceduralize target language knowledge already internalized in declarative form …(b) by drawing learners’ attention to form during communicative interaction in ways that allowed them to re-analyze and modify their nontarget output as they tested new hypotheses about the target language. (p. 274)

Although the role of negotiation and its possible effects on the learning process have recently received considerable attention in the field of SLA, most of the research in this area has focused on oral errors. However, the research findings on written errors indicate that when learners participate and become engaged in the feedback process, the effectiveness of feedback increases (Nassaji, 2007; Nassaji & Cumming, 2000).

In the present study, the researcher examined the role of two kinds of feedback in an EFL classroom in the context of addressing question formation. Question formation relates to the realm of word order in grammar. Taking word order into account, Pienemann (1989; 2007) asserts that it is developmental in that it is fixed and constrained by processing mechanisms. Pienemann’s processability theory maintains that the impact of teaching is restricted to learning of items for which the learner is ready. Therefore, “teaching can only promote acquisition by presenting what is learnable at a given point in time” (Pienemann, 1989, p. 63).

This study aimed at answering the following questions:

Does the question formation of participants receiving explicit feedback on their assignment differ significantly on the pre-test and post-test?

Does the question formation of participants receiving negotiation on form on their assignment differ significantly on the pre-test and post-test?

Is there any significant difference between question formation of the participants receiving negotiation of form and that of those receiving explicit feedback on their assignments?

In order to investigate the above research question empirically, the following null hypotheses were stated:

H0 (1): There is no statistically significant difference between the pre-test and post-test mean scores of the participants who receive explicit feedback on their assignment on question formation.

H0 (2): There is no statistically significant difference between the pre-test and post-test mean scores of the participants who receive negotiation on form on their assignment on question formation.

H0 (3): There is no statistically significant difference between the post-test mean scores of the participants who receive explicit feedback and the mean score of those who receive negotiation on form on their assignments on question formation.

A total of 31 male students participated in this study. The participants were of various fields studying at the Islamic Azad University of Qazvin, with an average age of 20. All had taken general English course with the researcher. The type of sampling employed in this study was cluster sampling. That is, the unit of selection did not involve individuals, but a group of individuals who were naturally together. The sample comprised two classes. The participants were supposed to be homogeneous because they have been filtered out by the university according to their English score on the university entrance exam.

The instruments utilized in the present study were two teacher-made tests which were qualitatively validated by two instructors’ judgments.

One was used to identify learners’ stage of development in terms of word order (a placement test) (see Appendix A). The items in this test consist of scrambled words. The learners’ task was to unscramble them. The test consists of 19 items, which were statements, negatives and questions. The reliability index of this test obtained through Kuder-Richardson (KR-21) formula was .73.

The other teacher-made test consists of 15 scrambled questions. Like the placement test, the learners’ task was to unscramble them. This test was served as both pre-test and post-test (see Appendix B). The reliability index obtained through Kuder-Richardson (KR-21) formula was .65.

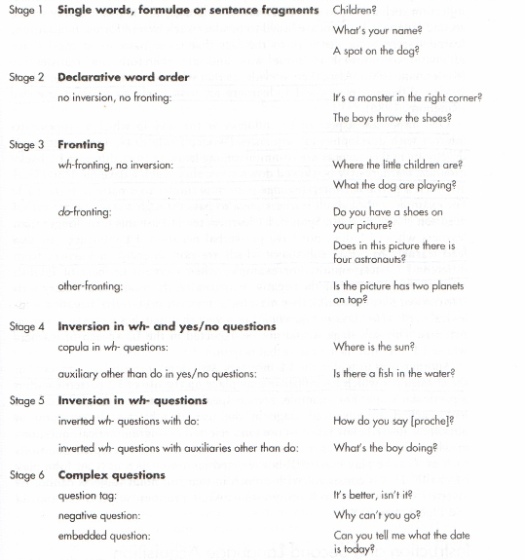

Certain procedures were adopted during this study. The sample comprised of two groups: a group receiving written explicit feedback on their own errors, the other group receiving negotiation on form on a sample of errors. Having run placement test, the researcher came to the conclusion that they were at the fifth level of developmental stages for question formation according to Spada & Lightbown’s (2002) scale (see Figure 1). In the next step, another teacher-made test on just question formation (at the students’ level of development) was administered as a pre-test to both groups. The final stage was administering the post-test.

Figure 1. Developmental stages for question formation (Spada & Lightbown, 2002, p. 125)

The design of this study was nonrandomized pretest-posttest design, one of the quasi-experimental designs.

The treatment procedure was carried out within ten sessions. At the end of each session, the learners were presented by six to ten items to be done as an assignment in the classroom. Some of the items were yes/no questions which were to be unscrambled to a question. Others were statements with some bold parts. The learner’s task was making a wh-question by omitting the bold part. The two following items are two examples:

- Yes/no question: her mother/she/has/bought/a nice present?

- Wh-question: He will go to the cinema tomorrow afternoon.

Having done the assignment, the participants delivered it to the researcher. For the next session, the researcher provided explicit written correction for the participants receiving explicit feedback and returned their assignments to them. In contrast, the other group did not receive any explicit feedback on their assignments, but they were provided by negotiation on form. That is, a sample of students’ errors was projected on the screen and then there was negotiation between teacher and students to correct the errors. In this phase, either a student was called or the whole class tried to fix the error. If the initial response was not successful, the teacher pushed and guided the learner(s) further towards identifying and correcting the error, allowing for more opportunities for negotiation and resolving the error. This treatment was audiotaped each session. Two examples of the treatment are as follows:

1. [The students are looking at this wrong question on the screen: Why they will go

to Dubai?]

T: Can you fix the error?

Ss: Why will they go to Dubai?

[The students are looking at this: Has him brought a nice shirt his uncle from Canada?]

T: Amir, what would you do to correct this?

S: Has his uncle brought a nice shirt him from Canada?

T: Try your best!

S: Has his uncle brought him a nice shirt from Canada?

Because of the nature of the feedback, those participants receiving negotiation on form were exposed to feedback time more than the other group. To compensate for the time, those who received explicit feedback were given the same amount of time to take a look at their errors and ask any question on their correction if they had. However, no negotiation was carried on. The researcher just provided them with the answer of their question.

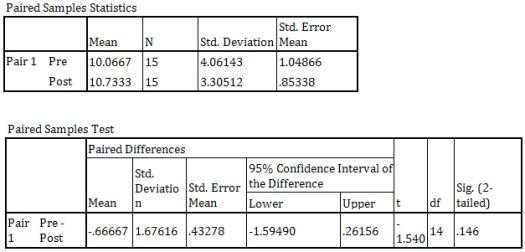

Investigation of null hypothesis 1: In order to investigate the possible difference between the pretest and post-test mean scores of the participants who received explicit correction on their assignments, a paired-samples t-test was carried out. As Table 1 shows, there was not a significant difference in scores (M = 10.7333, SD = 3.30512), t (14) =-1.540, p.05. Therefore, the null hypothesis is supported. By virtue of this finding, it can be claimed that providing students with explicit correction on their assignments does not lead to a higher performance of question formation, at least as far as the present study is concerned.

Table 1

Paired-samples t-test for participants receiving explicit feedback

Paired Samples Statistics

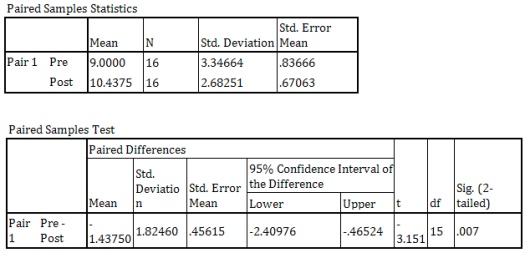

Investigation of null hypothesis 2: Conducting a paired-samples t-test, it was found that there was a significant difference in scores. As Table 2 shows (M = 10.4375, SD = 2.68251), t (15) =-3.151, p.05. As a result, the null hypothesis is rejected. In other words, there is statistically significant difference between the pre-test and the post-test mean scores of the participants who receive negotiation on form on their assignments. This significant change in the participants’ performance from the pre-test to the post-test can, therefore, be attributed to the type of feedback, negotiation on form, they received in the course of this study.

Table 2

Paired-samples t-test for participants receiving negotiation on form

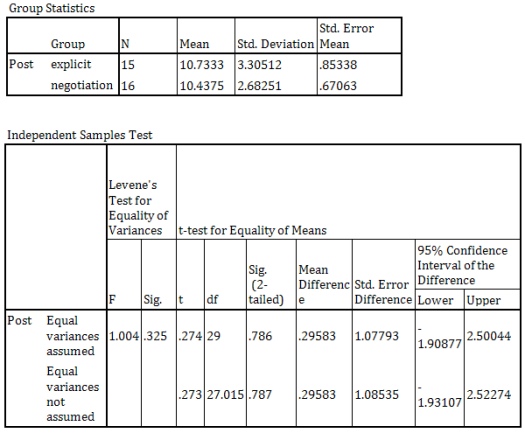

Investigation of null hypothesis 3: The researcher has carried out an independent-samples t-test to compare the mean score of the participants who received explicit feedback and that of the participants who received negotiation on form on their assignments. There was not a significant difference in scores for the participants who received explicit feedback (M = 10.7333, SD =3.30512) and the participants who received negotiation on form, t (29) =.274, p.05. The findings support the suggestion of null hypothesis 3 which denied the existence of any discrepancy in the mean scores of the two groups on the post-test; hence this null hypothesis is supported (see Table 3).

The findings of the first and second hypotheses are consistent with the earlier findings of Nassaji (2007) who claims that “the effectiveness of feedback increases when learners participate and become engaged in the feedback process” (p. 128). However, the finding of the third hypothesis goes against the effectiveness of the negotiation on form feedback in comparison with the explicit form feedback. Since learning is not a linear process, some possibilities have to be taken into account. One possibility is that a delayed effect may be at work (Ellis, 1990, 1994). According to the delayed effect hypothesis, “instruction does not seem to result in the immediate acquisition of new features, except in rather exceptional circumstances” (Ellis, 1990, p. 169). That is, although data did not show a statistically significant difference between the performance of the two groups on the post-test, instruction may “speeds up learning in the long term” (ibid.). Another possibility is that the instruction was not extensive enough. The instruction in this study carried out in only ten sessions, which may not have been sufficient for students to internalize what they have been presented.

Table 3

Independent-samples t-test for all participants

This study set out to determine the effect of explicit feedback and negotiation on form feedback on question formation of Iranian EFL learners. Based on the findings of the present study, it can be concluded that although negotiation on form facilitated the process of question formation in the participants receiving that kind of feedback, there was not a statistically significant difference between the performance of two groups receiving two different kinds of feedback (explicit vs. negotiation on form). However, it is important to note that the results reported here are based on data from two university EFL classrooms. Therefore, the findings of this study should be interpreted within the limits of the context in which the study took place. Finally, since the issue of corrective feedback is controversial in L2 learning, future research can duplicate the present study in different research designs.

Ellis, R. (1990).Instructed second language acquisition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Ellis, R. (1994). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R., Basturkmen, H, & Loewen, Sh. (2002). Doing focus-on-form. System, 3, 419-432.

Ellis, N. (2007). The weak interface, consciousness, and form-focused instruction: Mind the

door. In S. Fotos & H. Nassaji (Eds.), Form-focused instruction and teacher education: Studies in honor of Rod Ellis (pp. 17-34). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lyster, R. (2001). Negotiation of form, recasts, and explicit correction in relation to error types

and learner repair in immersion classrooms. Language Learning, 51 (suppl. 1), 265-301.

Lyster, R. (2004). Differential effects of prompts and recasts in form-focused instruction. Studies

in Second Language Acquisition, 26 (3), 399-432.

Lyster, R., & Mori, H. (2006). Interactional feedback and instructional counterbalance. Studies in

Second Language Acquisition, 28 (2), 269-300.

Lyater, R., & Ranta, L. (1997). Corrective feedback and learner uptake. Studies in Second

Language Acquisition, 20 (1), 37-66

Mackey, A. (1999). Input, interaction, and second language development. Studies of Second

Language Acquisition, 21 (4), 557_587.

Mitchell, R., & Myles, F. (2004). Second language learning theories (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Nassaji, H. (2007). Reactive focus on form through negotiation on learners’ written errors. In S.

Fotos & H. & H. Nassaji (Eds.), Form-focused instruction and teacher education: studies in

honor of Rod Ellis (pp. 117-129). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nassaji, H, & Cumming, A. (2000). What’s in a ZPD / A case study of a young ESL student and

teacher interacting through dialogue journals. Language Teaching Research, 4 (2), 95-121.

Nassaji, H., & Fotos, S. (2004). Current developments in research on the teaching of grammar.

Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 24, 126-145.

Nassaji, H., & Fotos, S. (2007).Issues in form-focused instruction and teacher education. In S.

Fotos & H. Nassaji (Eds.), Form-focused instruction and teacher education: Studies in honor of

Rod Ellis (pp. 17-34). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Norris, J. M., & Ortega, L. (2000). Effectiveness of L2 instruction: A research synthesis and

quantitative meta-analysis. Language Learning, 50 (3): 417-528.

Pienemann, M. (1989). Is language teachable? Psycholinguistic experiments and hypotheses.

Applied Linguistics, 10 (1), 52-79.

Pienemann, M. (2007). Processability theory. In B. VanPatten & J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in

second language acquisition. (pp. 137-154). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Schmidt, R. W. (1990). The role of consciousness in second language learning. Applied

Linguistics, 11 (2). 129-158).

Schmidt, R. W. (2001). Attention. In P. Robinson (Ed.). Cognition and second language

instruction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Spada, N., & Lightbown, P. M. (2002). Second language acquisition. In Schmitt, N.

(Ed), An introduction to applied linguistics (pp. 115-132). London: Arnold.

Truscott, J. (1996). The case against grammar correction in L2 writing classes. Language

Learning, 46 (2), 327-369.

Truscott, J. (1998). Noticing in second language acquisition: A critical review. Second Language

Research, 14 (2), 103-135.

Tsang, W. K. (2004). Feedback and uptake in teacher-student interaction: An analysis of 18

English lessons in Hog Kong secondary classroom. SAGE Publication, 35, 187-209.

Van den Branden, K. (1997). Effects of negotiation on language learners’ output. Language

Learning 47 (4), 589-639.

A teacher-made test served as a placement test

Word Order

Form a sentence using the following words.

sister / has / my / got / a dog

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

wrote / last week / they / at school / a test

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

give / the present / tomorrow / we / him / will

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

must / at five o'clock / leave / we / the house

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

tonight / want / to the cinema / to go / we

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

our holiday / will / at home / we / not / spend / next year

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

did / I / him / see / not / last night / at the party

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

to a party / not / we / tonight / going / are

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

to the cinema / we / want / not / do / tonight / to go

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

not / now / she / in England / is

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

right now / have / not / we / time / do

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

haven't / recently / seen / I / him

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

playing / the kids / are / OUTSIDE

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

were / EVERYWHERE / we / for / looking / you

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

the piano /my sister/ awfully /plays

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

play / at / you / the weekends / do / tennis

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

go / last night / out / you / did

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

the train / when / leave / does

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

him / she / did / the truth / tell / why

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

A teacher-made test served as both pre-test and pos-test

Question Formation

Form a QUESTION using the following words.

go/last night/ out/you/did /to your friend’s house

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

wear/he/does /a T-shirt/in the winter/in Canada

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

absent/the other day/has/who/been

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

to the cinema/Peter/is/going/now/this evening

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

was /who/driving/at half past seven/home

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

were/the children/yesterday afternoon /where/playing

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

bought/why/Catherine/has/a new bag/me

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

last night/her/at the party/ gave/who/a present

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

like to do /what/on holidays /Julia/does

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

Ashley/going/right now/where/is

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

right now/you/are/taking/a test/in this class

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

singing/who/is/a song/in bathroom

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

ask/did/her teacher/why/she/that question/this morning

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

has/how long/been/in Iran/Mary

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

sends/who/every day/a message/at this time/you

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------?

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Building Positive Group Dynamics course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|