Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge Rod Bolitho, the consultant to the project, Jamilya Gulyamova, the Project coordinator from the British Council, authorities of the institutions, the past and current members of the PRESET Project team, teachers and students involved in piloting and implementing the new curriculum.

Curriculum for Preparing Teachers of English in Uzbekistan: Now and Then

Nodira Isamukhamedova, Uzbekistan

Nodira Isamukhamedova (MA in TESOL, University of Leeds, UK, PhD in Linguistics, National Uz-bekistan University) is an Associate Professor at the Uzbek State World Languages University. She is ELT professional with extensive experience of teaching, teacher training at a University level. She has served as a National Coordinator to the partnership project of the British Council and the Ministry of Higher Education in Uzbekistan on reforming the English language pre-service teacher training pro-gramme across the country. E-mail: nodira.isa@gmail.com

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Fundamentals

Language improvement strand

Methodology strand

The cultural component

Independent study

Conclusion

References

This article presents a comparative study of the traditional and the new University BA curriculum for preparing future teachers in Uzbekistan. The new curriculum is the product of the collaborative project of the British Council and the Ministry of Higher Education. The article describes the philosophies underlying the curriculum, the aims and objectives of the contained courses as stated in relevant cur-riculum documentation.

Since gaining independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Uzbekistan has launched several salient reforms in the area of education. Even though, there were successful attempts at restructuring the edu-cational system, the content and the delivery of English Language Teaching (ELT) in Uzbekistan re-mained largely unaltered. However, the issue of a Presidential Decree on the Teaching of Foreign Languages in December 2012 [1], prioritising the learning of English from primary right through to postgraduate level, provided the momentum that was long-awaited and hoped-for. As an immediate response to the Decree, the new BA curriculum for preparing teachers of English at a University level was endorsed from September 2013 in all 18 institutions located in all 12 regions.

The reform, though it may seem revolutionary, is actually evolutionary. This curriculum is the product of a long-term partnership project between the British Council and the Ministry of higher and second-ary specialised education (MHSSE) in Uzbekistan. The project was launched in 2008 after the Baseline Study, i.e. analysis of the current situation to identify the starting points for a project, was conducted in 2007. The project (unofficially called the PRESETT project) was aimed at achieving lasting improvement in the standard of English language teaching in Uzbekistan by enhancing the learning experience of ELT PRESETT students and by setting clear exit levels of proficiency in English, referred to international standards.

So by 2012 the renewed curriculum had already been developed and piloted gradually in most of the involved institutions. This meant that a significant majority of university teachers of English received training and guidance on the implementation of the newly developed curriculum. The pilot findings revealed clear evidence of the success of the new curriculum as in language tests the students of the pilot groups outperformed their peers from the traditional classrooms to a considerable extent. The curriculum change process which is in place in Uzbekistan is challenging, yet inspiring like other re-forms in teacher education programmes around the globe [e.g., 2,3, 4].

As a National Coordinator to the project it was my honour to work closely with the project managers from the British Council, especially Jamilya Gulyamova, the Deputy Director of the British Council Uzbekistan, Rod Bolitho, the UK consultant, local authorities, a team of enthusiastic curriculum de-velopers, as well as pilot teachers. The experience that we gained together through the project has been shared through international and local publications and conference presentations. In particular, the re-flections on the factors contributing to successful change management [5], the involvement in the pro-ject as a way of continuous professional development [6] have been reported in peer-refereed journals, whereas challenges and opportunities of the reform, establishing professional learning communities through the curricular reform project were presented at IATEFL, NILE TESOL and UzTEA confer-ences. Nevertheless, the actual descriptions of the old and the new curricula were sporadic and patchy. With the aim to fill this gap, the present article seeks to compare and contrast the traditional and new curricula for preparing teachers of English in Uzbekistan. For this purpose, defining the terms ‘curriculum’ and ‘syllabus’ is seen as pivotal. Obviously, there are diverse definitions proposed by scholars [7,8,9]. We, the project members, regard a ‘curriculum’ in broad terms referring to “the totality of content to be taught and aims to be realized within one educational system" [9:4]. Whereas a ‘syllabus’ refers to the content or subject matter of an individual course/module. Thus a curriculum may or should contain several syllabi. In this vein, a national curriculum is the umbrella framework which embraces the content, the aims and the methodology of the English language teacher education programme.

At the time of writing this article, there is one comprehensive document embracing all the components of the new curriculum. Meanwhile, the term ‘traditional’ or ‘old’ for the purposes of this article have been used for any materials related to the curriculum, syllabi developed by different related institutions, coursebooks or handbooks used before the adoption of the new curriculum at a national level in Sep-tember 2013.

One of the distinctive features of any University level curriculum in Uzbekistan is that they are loaded with various subjects not directly related to students’ specialty. This comes in the frame of the state’s vision of preparing a harmoniously developed generation who are knowledgeable, at the same time, politically and socially active citizens possessing high moral values [10]. So, like other University level curricula in Uzbekistan the curriculum for preparing specialists of English is divided into 4 blocks of subjects: humanitarian and socio-economic subjects (about 25% of the whole curriculum), mathematics and natural sciences (10%), general professional subjects (40%), specialisation subjects (15%), as well as additional subjects’ block (10%). The 4 year Bachelor programme is offered through nearly 30 hours of weekly contact time extended to almost 40 weeks annually. Admittedly over the last years the MHSSE is making efforts to decrease the number of contact hours gradually by allowing more time for independent work. Yet the curriculum still remains to be rather packed [11:116-117]. There are usually more than 10 subjects to be studied per term ranging from specialty courses to geography, mathematics, political studies, history of Uzbekistan and many more. The special subjects are built around the fol-lowing strands – Linguistics (Theoretical Grammar, Theoretical Phonetics, Lexicology, Stylis-tics), British and American Literature, as well as practical classes of English.

From the outset we were aware of certain ‘no-go’ areas in the general curriculum which was governed by the Ministry. Based on the Baseline Study and upon consultation with the authorities, in the framework of the project, the decision had been made to focus on the two strands, namely Language Improvement and Methodology strands. These two strands in terms of study load comprise about 50% of the overall 4-year Bachelor Degree program, with nearly 1700 contact hours.

Indeed, the language improvement and methodology components are the most essential, if not the sole, components in any PRESET programme for teachers of modern languages in the world. Undoubtedly, a language teacher should possess a deep and extensive knowledge of the target language as this is fun-damental to good language teaching [12]. In contrast to language teacher education programmes in some western countries, in Uzbekistan, where English is a foreign language and learners have limited access to the target language and native speakers, the prioritisation of language improvement courses is justified. [13]. On the other hand, teachers should be methodologically competent to be able to perform teaching tasks effectively [14].

It should be noted that besides these two core strands there are several other added-value components that were also reconceptualised – Intercultural learning, Independent study skills development, and Teaching Practice as well as Classroom research. In the following sections I will try to analyse each of the components in more detail.

Traditional curriculum

The language improvement component of the traditional curriculum lasted for 4 years, offering in average 12 contact hours per week. The component was broken down to several courses like Practice of Oral and Written Speech (aka Analytical Reading), Home Reading, Practical Phonetics, Practical Grammar, Conversation and in some contexts Current Events. Nonetheless, there was usually one syllabus for all the courses. Furthermore, the syllabus was based largely on one textbook series [15]. The textbook series (1,2,3,4) developed by a group of Soviet authors and edited by V.D. Arakin in 1960s had seen numerous editions even in the new millennium with minor modifications.

The coursebook by Arakin was written in the times when teaching and learning English was “politically unpopular, suspect and dangerous, since it is inevitably implied ‘mixing with foreigners’, who were officially called ‘potential enemies”, when teachers “never set their eyes – or ears – on a native speaker of foreign language, taught generations of students without any equipment, without authentic foreign language teaching materials [16]. In such harsh times it was safer to refer to literary texts in English as the source of language. Clearly, such a tendency lingered on even in the new century as the aim of the traditional curriculum which is written in the Uzbek language is translated as – the practice of oral and written speech as the specialty course implies reading and understanding literary works of the target countries, getting information on the main events and phenomena through reading press as well as being able to retell and give a written account of the gained information (translated by the author) [17: 3].

The analysis of the existing traditional curriculum documentation did not reveal any clear requirements to the exit level of graduates, let alone the interim levels among the Years of studies. Instead, the text-books served as the milestones of achievement depending on which series (1,2 or 3,4) a student has covered. Sadly, even the textbooks in use did not state any sound level descriptors. Consequently, teachers and obviously students were not able to describe their own level of proficiency [12].

Being based on mainly one or two textbooks a traditional syllabus usually indicated the Unit number and/page number of the relevant textbook. The syllabus, like the textbooks, were organised into themes, grammar, phonetic points. An excerpt from such syllabus is given in Figure 1.

Lesson One: Meals

- Phonetics: About Intonation; Intonation of Pa-renthesis

- Grammar: The Present Perfect Tense; Impera-tive Sentences in Indirect Speech; Special Questions in Indirect Speech

- Conversation: Text-Dialogue: Meals (from Essential English for foreign Students, Book 2 by C.E. Eckersley pp.199-203)

- Reading: A Flower-girl Eliza is Having Her First Lesson of English, An extract from “Pygmalion” by B. Shaw.

- Home Reading: Introduction, Chapter I, pp.7-15 from “Jane Eyre” by Charlotte Bronte

|

Figure 1. An excerpt from Syllabus on English language course for first year students majoring in English [20].

As it can be seen from Figure 1 the curriculum represented the Classical Humanistic model where a curriculum consists of the content that needs to be transmitted to the learner. The content is “a valued cultural heritage, the understanding of which contributes to the overall intellectual development of the learner” [19: 71]. Such a model of curriculum is concerned with making sure learners master the grammar rules and vocabulary. Exemplary teaching procedures consist of explanation of rules, memorization of lists of vocabulary, making up sentences using the taught grammar point or vocabulary, drilling, translation exercises.

The Practical Grammar course lasted for 2 years and covers a wide range of grammar points. However, there was an army of teachers who believed grammar courses were never enough and proposed extending the course for all four years of study [18]. Another salient feature of the traditional curriculum is teaching phonetics, which aimed at teaching students pronounce discrete phonemes. The procedure for teaching phonetics included “explanation of the articulation of the phonemes; demonstrating the articulation of the phonemes by the teacher with the help of visual aids or schemes; reproducing the phonemes by the students with the help of a mirror under the control of the teacher; the pronunciation of the phonemes by the students individually or in chorus; listening to the tape and repeating every word in chorus after the announcer; the individual reading of words by the students with the help of a mirror under the control of the teacher; the first training reading of words by separate students with the simultaneous listening by means of ear-phones; the second training reading of words by every student with correcting the errors; controlling reading of the exercises [20: 4].

The source for learning the grammar points and vocabulary usually came from literary texts representing ‘high culture’. Texts were taken from original British and American literature of XIXth and XXth cen-turies. Thus reading was believed to be the main skill in mastering the language. Reading skills implied: ‘Silent reading’ and ‘Reading aloud’ - ‘silent reading - the student should be able to read and make grammatical analysis and understand literary, political texts with the speed of 350 signs per minute; reading aloud – a student should be able to read aloud expressively not difficult texts’ [21:6]. Reading sub-skills such as scanning and skimming were rarely indicated in syllabi as an aim for teaching reading.

So, reading aloud, retelling, translation, and learning by heart 1-2-page long texts were the usual routines in traditional classrooms.

Teaching vocabulary was another essential part of the traditional curriculum, even though there was no separate course devoted to Vocabulary. Instead, vocabulary was used as the overarching requirement for each level of study. For instance, Year 2 textbook targeted at enriching learners’ active vocabulary with 850 lexemes (550 stem words and 300 collocations). As the authors claimed the choice of vocabulary was governed by “their usage, theme of the lesson as well as need for widing learners’ vocabulary through synonyms, derivatves and others” [22:2].

Issues of register were rarely addressed in the traditional curriculum, thus almost no reference to spo-ken English. Outdated vocabulary, or even direct translations from the Russian language occurred even in new editions in 2005 – If it doesn't rain, I shan't have to take my umbrella with me… The children found that it would be interesting to go on an excursion [22:3].

Speaking skill development was stated by teachers and students to be the most important skill but, unfortunately, it was their weakest point [18]. The traditional curriculum claimed to develop learners’ skills of producing monologues as well dialogues, both prepared and spontanous speech. There were certain communicative speaking activities embedded in some syllabi such as making presentations, debates, role plays etc. However, the practices of retelling, answering questions, discussions, reading ready-made dialogues aloud in pairs prevailed. In fact, a handbook for Conversation course developed by one of the Universities in Uzbekistan is in fact a book with thematical, non-authentic dialogues with their translations alongside [23] (see Figure 2 for an excerpt).

Dialogue:

An English language evening |

Transtion into Uzbek:

Ingliz tili kechasi

|

- Were you at the Tashkent Teacher’s Club last night?

- No, I wasn’t. What was on there?

- By whom was it arranged?

- Was it well attended?

- The hall was filled to capacity.

- Very many people: pupils, their parents and teachers were anxious to be present.

- What was the performance like?

- The program included recitations of English and American poetry, singing of songs and acting of excerpts and scenes from English and American plays.

- All the actors were Moscow school-children

|

- Kecha kechqurun Toshkent o’qituvchilari uyida bor oldingizmi?

- Yo’q, u yerda nima bo’ldi?

- Kim tashkillashtirgan edi?

- Odam ko’p edimi?

- Zal to’la edi.

- Konsertga bormoqchi bo’lganlar talaygina edi: o’quvchilar, ularning ota-onalari, o’qituvchilar.

- Qanaqa ko’rinish edi o’zi?

- Programmada qo’shiqlar Ingliz, Amerikalik shoirlar sherlaridan na-munalar, shuningdek ingliz va ameri-kancha sahnalardan ko’rinishlar.

- Aktyorlarning barisi Moskva maktab o’quvchilari edi.

|

Figure 2. Handbook for Conversation course [23:27].

In this vein, accuracy (phonetic, grammatical, lexical) wasconsidered to be the focal point in developing students’ speaking skills. Other facets of effective communication such as fluency, coherence and cohesion were neglected. As a result, students and teachers voiced their concerns about their speaking skill – ‘I know grammar and many words but can’t speak’, ‘I am afraid to speak in front of my students as I may make mistakes’[18].

The most neglected skills of all in traditional curriculum were the listening and writing skills. If the former might be justified by poor resources, the latter seemed to be left out without any sound explanation. Again, in writing, as in other skills, prominence was given to form rather than meaning: “A student should be able to write dictations, containing the content vocabulary, beautifully and free of mistakes. Orthographic dictation should be about 180-200 words and not more than 5 mistakes should be allowed” [21:6].

Translation was regarded as the fifth language skill in traditional syllabi. For this reason, translation exercises appeared in all the courses and the coursebooks. However, as most coursebooks in use were written in Russia, the translation exercises were all in the Russian language. This created extra difficul-ties for Uzbek natives with poor Russian language proficiency.

In a nutshell, the language improvement strand of the traditional curriculum seems to be underpinned by Classical Humanist tenets implemented through grammar-translation methods. Use of classical lit-erary texts, rote learning, primacy of form over meaning, predominant focus on accuracy rather than fluency, and emphasis on translation are the characteristics of the old curriculum.

New curriculum

The most salient feature of the new curriculum is in its link with the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). The CEFR [24] has been used to define exit levels, in the develop-ment of syllabi for language courses, in designing assessment tasks as well as the exit test. Like in many countries where the CEFR has been applied [e.g.25, 26], it had a positive impact on the whole programme. The success of the PRESET project led to the development of national educational stand-ards based on CEFR for all levels of education: from primary right across the higher education. Thus, with the help of the project team, exit levels referenced to CEFR were defined for school-leavers, graduates of vocational colleges and higher education institutions. Likewise, this initiative has been extended to the standards for teaching other modern languages, such as German, French and Spanish.

The exit level for BA graduates in English programs was set ambitiously at C1 level, with interim levels for Year 1 – B1, Year 2 – B2. Thus the main objective of the revised curriculum reads: “Graduates of the program as future teachers of English will be expected to demonstrate: ability in listening, reading, speaking and writing to the level of C1 on the CEFR and sufficient understanding of the pedagogical implications of knowledge about language” [27:5].

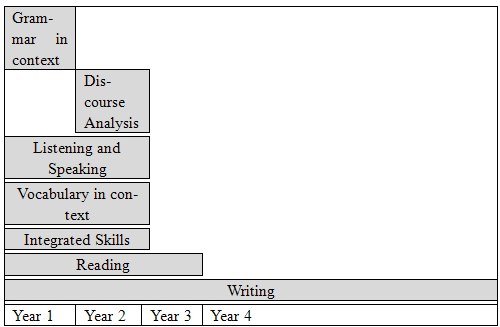

The set objective stipulated the choice of the courses for the Language Improvement strand. The dis-tribution of the language improvement courses can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The new curriculum for BA in English: the Language Improvement strand

Each course for each year of study is documented as a separate syllabus. The syllabi sets out the aims and objectives of a course, indicative content, approaches to teaching and learning, learning outcomes, as-sessment profile, as well an indicative bibliography. Besides, to exemplify the curriculum principles in practice sample lesson plans were developed for each course. The Assessment profile has a more detailed explanation in the form of Assessment Specifications where sample assessment tasks and criteria are given for summative and formative types of evaluation.

In contrast to the traditional Grammar course, the new course has been named ‘Grammar in con-text’ to put the emphasis on learning grammar not for the sake of learning rules, but for the sake of effective communication. Thus the objective for the course is set as: “By the end of Year 1 students will be able: to use grammatical structures to convey meaning in communication; recognise and use structures appropriately both in spoken and written English; to under-stand the link between form and meaning of new grammar structures in different communicative settings; to notice the characteristic features of English grammatical patterns and structures and compare them with those in L1 to enhance learning of those patterns and structures; to understand the importance of accuracy in communication; to use grammar reference books independently [27].

Similarly, the ‘Vocabulary in context’ course also emphasizes not only enlarging students’ passive vocabulary but their skill in using active vocabulary in communication. Besides, a range of strategies for learning and storing vocabulary, guessing, working with dictionaries and corpora are there to be taught in this course which lasts for two years.

In contrast to the traditional curriculum the new one does not have a separate course on phonetics. Phonological features are mainly dealt with in the Listening and Speaking course. Logically, pronunciation, stress, intonation, rhythm relate to, and are actualised in, authentic speech.

Later in Year 2 a course on ‘Discourse Analysis’ is introduced. The learning outcome states that students by the end of the course should have developed: “the ability to distinguish and ana-lyze specific features of spoken and written discourse for building effective communication; the ability to distinguish specific features of different written discourse types and genres; the ability to understand how grammar, lexis and phonology are used in discourse” [27].

A sample task given in Figure 4 can illustrate the concept of the course.

The1 schoolmaster was leaving the2 village, and everybody3 seemed sorry. The4 miller at Cresscombie lent him5 the small white tilted cart and horse to carry his goods to the city of his destination, about twenty miles off, such6 a vehicle proving of quite sufficient size for the departing teacher’s effects (from Jude the Obscure, by Thomas Hardy).

- How many schoolmasters were there in the village? How do you know?

- Does the reader already know which village is meant here?

- Who does this refer to?

- How many millers were there at Cresscombie? How do you know?

- Who does this refer to?

- A vehicle like what?

- Which of these references are anaphoric and which are exophoric?

|

Figure 4. A sample task for the Discourse Analysis course [28].

The Reading course enjoys a longer span and covers a range of authentic texts from menus to websites, as well as professional articles. Reading skills and strategies such as skimming, scanning, reading for gist and others are highly emphasised and practised.

The Writing course which is offered for all 4 years is definitely the most striking difference compared to the old curriculum. Students learn how to write gradually from simple letters to argumen-tative essays. The culmination of the writing course is the Year 4 where students are given guidance and support on writing their final qualification papers. Another distinctive feature of the course lies in the adopted methodology – a process approach to teaching writing. This approach recognises writing not as a linear process, but as complicated and cyclical. So, students go through the whole process of writing – from brainstorming and planning to writing first drafts, revisions, proofreading and others together where the teacher and peers provide feedback and support at each stage [29,30,31]. It takes about a month to write up a final version of a piece of writing.

The most popular course among students and teachers is named ‘Integrated Skills’. It aims at developing learners’ communicative competence through integration of all skills and language areas. The format of the course is what it makes it so popular among students. The course is entirely built on project tasks chosen for each month. Students work on each task in small groups inside and outside the classroom. The project tasks vary from designing a brochure on healthy lifestyle to creating a short film on family values. The project based approach helps to connect the classrooms with the real world and serves as an inspiring tool for developing language skills in integration [32,33,34].

One of the ways of integrating the language courses is through the adoption of a topic-based approach to the curriculum. In our context, topics with a wide range of subtopics were chosen for each month. Over two years, all language courses (i.e. Listening and Speaking, Vocabulary, Reading etc.) are linked through topics. The suggested topics can be narrowed down to meet students’ needs and interests and to promote their critical thinking. For example, Health may be used as a topic in all language courses by narrowing it down to such subtopics as visiting a doctor, illnesses and human body, healthy lifestyle, smoking, alcohol drinking, drug addiction, traditional and modern medicine, AIDS, opportunities for disabled people etc.

Topic-based integration allows students to regard the curriculum holistically, enables them to use and recycle the learnt vocabulary on a specific topic in writing, speaking and others. The variety of sub-topics allows flexibility for teachers in finding the resources and keeping students’ interested and in-volved. For example, Health can be explored in Writing through filling in a form at a Hospital, whereas the Integrated Skills course students may be involved in creating a poster based on a survey they have conducted about what people in Uzbekistan do to keep fit.

Thus the new curriculum was constructed with the view of Communicative Language Teaching, Task-based learning, a Project-based approach, topic-based integration, and Process-orientation prin-ciples.

The traditional curriculum had only one course specifically targeted at teaching the English language. It was the methods course which described the theoretical rationale and practical implications of language teaching approaches, methods, procedures, and techniques. This kind of traditional approach had been practised and reported widely [35,36,37,38].

The syllabus for this course named “Methods of teaching a foreign language” contained 50 academic hours. The topics included theoretical background of methods of teaching; psychological, linguistic underpinnings of the methods of teaching; aims of teaching a foreign language; methods and principles of teaching a foreign language; history of methods; history of teaching English in Uzbekistan; teaching grammar, pronunciation, vocabulary, speaking reading, writing and listening; lesson planning; planning extracurricular activities [39].

Thus, the course heavily relied on the annals of teaching foreign languages. Practical issues like teaching skills and language areas were covered to a lesser extent. Even so, these topics were taught in a pre-scriptive manner, offering “a recipe books or cookbooks for teaching” that was duly criticized in the literature [38].

The course was delivered through a set of lectures (a lecturer read out from script, occasionally shooting questions at students) and seminars where students were supposed to retell what they had been told during the lectures. The course was usually delivered in either Uzbek or Russian language.

In the global ELT mainstream there has been a transition from methods to methodology in line with constructivist theories of learning – “a shift away from a top-down approach to methods as “products” for teachers to learn and “match” and toward a bottom-up approach to methodology as reflections on experiences”[38]. In terms of models of teacher education described by Wallace – the ‘craft’ model, the ‘applied science’ model and the ‘reflective’ model [40] – the traditional curriculum would prevailingly fall into the category of the ‘applied science’ model. In contrast to the ‘craft’ model which focuses mainly on imitative and static experiential learning, the ‘applied science’ model takes into account the latest developments in the area. However, the fodder for criticism is the split between re-search and professional practice. Such a model was typically housed in Universities like in Uzbekistan, where the University lecturers would impart the theoretical knowledge to prospective and current classroom teachers. It was up to the classroom teachers to put the knowledge into practice and if any-thing went wrong, the culprit was the teacher, who probably had not understood the theory well. This kind of belief led to downgrading of “the value of the classroom teacher’s expertise derived from experience” [40].

The Reflective model shifts the perspective of perceiving teachers as ‘consumers of knowledge’, ‘empty vessels’ to be filled in, to acknowledging teachers as thinkers, practitioners who construct their own working theory – in short, a ‘reflective practitioner’ who theorizes from practice [40,41].

Thus, several objectives were put forward in the methodology strand of the curriculum according to which graduates are expected to demonstrate:

- sufficient understanding of the pedagogical implications of knowledge about language;

- practical understanding of how learners learn languages;

- ability to critically evaluate, adapt and write materials;

- ability to plan and deliver lessons and sequence of lessons;

- understanding of a range of teaching approaches and ability to apply them according to the teaching and learning context;

- understanding of approaches to testing and assessment;

- ability to evaluate and reflect upon their own learning and teaching;

- ability to research their own practice;

- competence in the area of language awareness and language analysis for pedagogical purposes;

- a clear vision of the role of English in international communication” [27:5].

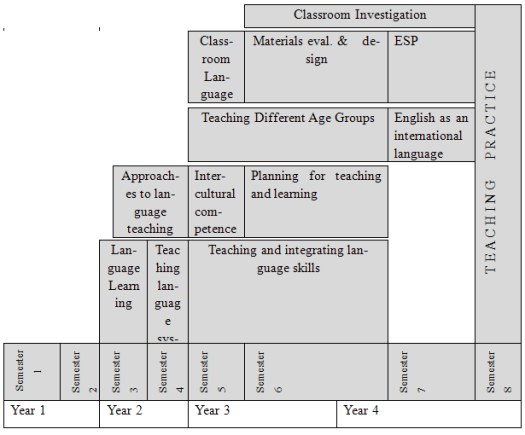

To achieve the defined objectives a set of courses were developed which start from Year 2 and increase year by year. Meanwhile the language courses decrease in number of the offered courses and hours. In fact, the hours for the methodology strand are taken from the language improvement strand in the tra-ditional curriculum. The list of methodology courses are given in Figure 5.

The courses are delivered in the form of workshops organized based on the Experiential Learning Cycle devised by Kolb [42] and its adaptations to teacher training contexts [43, 44]. The model assumes stages of experiencing, reflection, conceptualization and active planning (see Figure 6 for a sample lesson). Experience (individual or shared; past or present) can also be presented as ‘loop input’ [45] which presumes modelling a training activity.

The added value of the new curriculum that it helps students to gradually build their skills in doing classroom research and reporting the results in the form of their final Qualification paper. While Classroom Investigation course among other topics discusses Research Methods, Data Analysis tools, Writing 4 deals with academic conventions like how to write a literature review (structure types, useful phrases etc.). This was not the case in the traditional curriculum; the allocated supervisors carried sole responsibility for helping students to work on their thesis. In reality, it was almost impossible for a supervisor to guide students who have almost no knowledge and skills in doing research. That often resulted in plagiarism, frustrations of students and supervisors. Similarly, the traditional curriculum could not prepare students for the Teaching Practice effectively. In contrast, the new curriculum gives clear and step-by-step guidance for the Teaching Practice for the parties involved: the students, the Universi-ty-based supervisors, school-based mentors.

Figure 5. Methodology strand of the new curriculum

Lesson outline

Course: Teaching and Integrating Language Skills

Topic: Task-based learning as a way of teaching skills in integration

Lead-in

Objective: to explore students’ perceived beliefs to start where they are

Discussion of the terms exercise, activity, and task: Do you think these terms are similar? Or is there any difference? What do they mean? Can you give any examples?

Activity 1 Task

Objective: to expose participants to a typical task – ‘new’ shared experience

Students are exposed to a typical task which targets development of all skills in integration.

The offered task can be an adaptation of the task shared by D.&J. Willis http://willis-elt.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/EmpireStateBuildingfinal.pdf

Activity 2 Reflection on the experience

Objective: to give participants an opportunity to reflect on the task

Structured reflection on the experienced task: Will the activity engage learners' interest? Is there a primary focus on meaning? Is there a goal or an outcome? Is success judged in terms of outcome? Is completion a priority? Does the activity relate to real world activities?

Also reflection on their own experience as learners: Have you experienced such tasks in your English language classes in school? In the University? What were they like? Did you enjoy them? What are the advantages of such tasks?

Activity 3 Input

Objective: to let students construct their understanding of TBL based on the reflection on the experience and theoretical input.

Discussion of related readings and summarizing the principles of TBL. For example, Willis J. (2008) Six types of task for TBL. http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/six-types-task-tbl; Willis J. (2008) Criteria for identifying tasks for TBL https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/criteria-identifying-tasks-tbl

Activity 4 Active planning

Objective: to let students plan further steps.

Students (in small groups or individually) turn a traditional activity to a task (including pre and post task stages) for a specific group of learners in mind. They have to make sure to address all lan-guage skills and language areas.

Example of an activity to be upgraded as a task:

Work in pairs. Tell your partner about how you spent your weekend.

|

Figure 6. Outline of a methodology lesson exemplifying the Experiential Learning Cycle [28].

It should be admitted that it is difficult to differentiate some of the courses into Language or Method-ology such as Independent Study Skills, Classroom Language, and Developing Intercultural Compe-tence. Therefore to some extent the division is provisional as close interaction between the two strands is assumed in the process of preparing teachers of English language.

The presence of a cultural dimension in foreign language teacher education programmes has a relatively long history. In this vein, the traditional curriculum offered a course titled “Country study” which aimed at giving factual information on geography, political set up, traditions and other components of big ‘C’ culture [46,47,48]. In English language classes, as well, there were topics targeted at raising students’ awareness of cultural facts of the target country and their own, in this case mainly the USA, the UK and Uzbekistan [49].

Latest developments in this area put the emphasis on developing an ‘intercultural speaker’- someone who has an ability to interact with ‘others’, to accept other perspectives and perceptions of the world, to mediate between different cultures[50,51,52]. The components of intercultural competence contain knowledge, skills and attitudes for effective interaction. Thus, the new curriculum aims to de-velop students’ intercultural competence through tasks within the Integrated Skills course as well as providing a separate course on Developing intercultural competence. Typical activities on developing intercultural competence within Integrated Skills course would be case studies, projects, tasks aimed at discovering beliefs, values, behaviours of other cultures (not limited to only An-glo-American culture), comparing other cultures with one’s own, interpreting, explaining, relating events or documents of cultures. For instance: Students are asked to respond to the following situa-tion: “Imagine an American or Japanese finds your group’s webpage/blog in the Internet. What things might they find unusual or strange in your webpage/blog. Are there any cultural elements that are known only to the residents of Uzbekistan? If there are, so what adjustments should you make to make it understandable to foreigners? [27].The course on Developing Intercultural Competence in Year 3 aims at developing students’ intercultural competence with its implications for teaching English [27]. The course covers such topics as notions of culture, cross-cultural awareness and intercultural competence, extralinguistic issues in cross-cultural communication such as body language, taboos, stereotypes, ways of expressing politeness, dealing with culture clashes and others. So this is the course for students to conceptualise their own intercultural competence, and make plans for their prospective teaching practice. To this end, the course looks at such sources for teaching and learning of culture as media, films, literature as well as materials like coursebooks, lesson plans for analysing intercultural issues. The pinnacle of the course is the development of materials by students for teaching intercultural concepts. Ultimately, students by the end of the intercultural learning component of the curriculum are expected to have developed: “the ability to think critically about and resolve problems in intercultural communication; a high level awareness and understanding of linguistic and extralinguistic issues in communication of their own and target culture; the ability to evaluate, adapt, design materials for teaching culture” [27].

Another dimension of the cultural component is the acknowledgement of the English language as an international language. Thus teaching English is “no longer linked to a single culture or nation but serves both global and local needs as a language of wider communication” [53:24). A course named ‘English as an International Language’ is aimed at developing students’ understanding and critical awareness of the linguistic, historical, social and cultural circumstances contributing to the development of English as an international language; enabling them to identify and differentiate be-tween varieties of English [54,55,56]; empowering them to make informed choices while deciding on the varieties of English in their future teaching practice.

To sum up, the traditional curriculum in terms of the cultural dimension is targeted at imparting knowledge on big C culture of Anglo-American countries. In contrast, the new curriculum targets at developing learners’ intercultural competence involving critical awareness, skills and open attitudes thereby enabling them to interact with different cultures. In this way, students come to see English as a means of international communication.

One of the positive moves in higher education in Uzbekistan over the last years was the recognition of independent learning as increasingly important. According to the national standards 24 academic hours should be allocated weekly for students’ independent study. Almost no guidance as given on how these independent study hours should be best used. Consequently, most universities organized so called ‘in-dependent study classes’ where students would come and do their homework in presence of a teacher [57:15]. Topics and activities are suggested in each subject syllabus. The activities usually replicate the classroom practices, i.e. students are given extra texts and asked to read and retell, translate, do some grammar or vocabulary exercises [58]. Moreover, independent study is also assessed in each course.

In contrast, the new curriculum regards independent study as an integral part of the courses. Students are expected to devote this time to reading, research and preparing assignments. It is assumed that stu-dents who use the independent study hours conscientiously to their advantage will achieve better re-sults in course assessments than those who do not. However, there is no formal assessment of this element of the curriculum as it is impossible to monitor and to subject to criteria. There may be some evidence in reflective writing, but in reality this is already assessed against appropriate criteria within the overall assessment criteria for each module.

To be able to make best use of the allocated independent study and the whole learning experience within higher education institutions, a student should be independent and autonomous. An autonomous learner is someone who takes responsibility for his/her learning deciding what, how, when and where to learn [59,60]. In the new curriculum learner autonomy is regarded as a set of skills and strategies that need to be developed in students who to a large extent come from teacher-dominated backgrounds. For this purpose, the special course titled ‘Independent Study Skills’ was incorporated. The course introduces the study and transferable skills required in a higher education environment. It covers many areas of university study such as reflection, ability to make independent decisions, awareness of own learning styles, self-assessment, setting learning goals, managing time, using library and Internet resources and others. Independent study skills then continue to be part of other courses of the curriculum. For example, one of the assessment tasks within Listening & Speaking Year 2 course requires students to reflect on their proficiency and make further plans: “Write a reflective essay of about 200 words using the following points: the level you think you have reached according to the CEFR in terms of listening, spoken production and spoken interaction (please give examples); describe any problems you have had or still have with listening, spoken interaction and spoken production; the level you would like to achieve by the end of Year 4; describe what exactly you would like to be able to do in each skill: listening, spoken production and spoken interaction; describe how you are going to achieve your objectives, specific actions you are going to take” [61]. To be able to do this task, they need to be able to self-assess, to reflect on their learning, set realistic plans which are the characteristics of an autonomous learner.

So, independent study in the traditional curriculum was usually treated as formal time allocated for doing extra activities independently but in the presence of a teacher. The extra work designated for independent study is assessed separately, then summed up to the total score of a student in each course. In the new curriculum, independent study is built in to any assessment tasks within a course. Inde-pendent study is believed to be a set of skills that need to be developed in students to enable them to make the transition from their teacher-dependent mind-set to autonomy.

Thus, the comparisons between the old and the new curricula made it possible to summarise the philosophies embodied in the relevant curricula (see Figure 7). Due to the size constraints some aspects of the curricula were left out without further elaboration. However, I believe the article sheds some light into the ELT context in Uzbekistan in general.

| Traditional curriculum | New curriculum |

| Teacher-centered | Learner-centered |

| Classical Humanism | Social Constructivist |

| Applied science model of teacher training | Reflective model |

| Knowledge-based approach | Competence-based approach |

| Cultural knowledge | Intercultural competence |

| Grammar-translation | Communicative Language Learning |

| Teaching about the language systems | Teaching how to use the language in communication |

| Focus on form rather on meaning | Language forms as an aid to creating meaning |

| Emphasis on accuracy | Balance between accuracy and fluency |

Rote learning

Reading aloud

| Task-based approach

Experiential learning |

| Norm-referenced assessment | Criterion-referenced assessment |

Figure 7. Philosophies underlying the curricula

However, these assumptions should be regarded as generalisations, presuming exceptions. It is not our aim to label the old and the new curricula in black and white colours. There have always been enthusiastic and dedicated teachers experimenting with innovative ideas despite all the economic, social, political constraints. Thanks to such teachers the reform of the curriculum has been possible.

Presidential Decree (PD #1875) of the Republic of Uzbekistan on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (2012). Xalq so’zi Newspaper, 11.12.2012, Issue 240 (5660). Available online in Uzbek and Russian languages at: http://www.lex.uz/pages/getpage.aspx?lact_id=2126032

Fullan, M. (2007). The New Meaning of Educational Change. Routledge.

Korthagen, F., Loughran, J., & Russell, T. (2006). Developing fundamental principles for teacher education programs and practices. Teaching and teacher education, 22(8), 1020-1041.

Niemi, H. (2011). Educating student teachers to become high quality professionals-a Finnish case. CEPS Journal, 1(1), 43-66.

Gulyamova, J. & Isamukhamedova, N. (2012). English Reforms in Uzbekistan (excellent examples of partnership and co-creation). Teacher Trainer Journal, Spring/March 2012 - 26 /1, 7-9.

Gulyamova, J., Irgasheva, S. & Bolitho, R. (2014). Professional development through curriculum reform: the Uzbekistan experience. Innovations in continuing professional development of English language teachers (ed. by D.Hayes). London: British Council, 45-62. Available online at: http://englishagenda.britishcouncil.org/books-resource-packs/innovations-continuing-professional-development-english-language-teachers

Brumfit, C.J. ed. (1984). General English Syllabus Design. Curriculum and Syllabus Design for the General English classroom. New York: Pergamon Press, Maxwell House.

Nunan, D. (1988). Syllabus Design. Oxford University Press.

White, R. (1988). The ELT Curriculum: Design, management, innovation. Oxford: Blackwell.

National Program for Personnel Training.

Education in Uzbekistan: Matching Supply and Demand (2008). National Human Development Report. United Nations Development Programme. Available online at:

Bolitho, R. (1988). Language awareness in teacher training courses. In Duff (ed.). Explorations in teacher training, 72-84. UK: Longman.

Cullen, R. (1994). Incorporating a language improvement component in teacher training programmes. ELT Journal, 48(2), 162-172.

Reynolds, A. (1992). What is a competent beginning teacher? A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 61(1), 1-35

Bolitho, R. Materials used in Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. In: B. Tomlinson (ed.) (2008): 213-22

Ter‐Minasova, S. G. Traditions and innovations: English language teaching in Russia. World Englishes 24.4 (2005): 445-454.

Matyakubov, J.& G.Atakhanova. (2008). Syllabus for the course Oral and Written Practice of English. Tashkent: Uzbek State World Languages University. (in the Uzbek language)

PRESET Baseline Study Report. (2008) Tashkent: British Council.

Richards, J. C., & Renandya, W. A. (2002). Methodology in Language Teaching: An anthology of current practice. Cambridge University Press.

Nigmatov, H., Shermatov, A., Ismailov, A., Rakhimov, G., Yakubov, F, Ne’matov, B. (2010). Practical Course of English: first year a handbook for the first year students of foreign languages institutes. Samarkand: Samarkand Institute of Foreign Languages.\

Tursunboyev, B. (2007). The working syllabus on the course Oral and Written Practice of English. Karshi: Karshi State University. (in Uzbek).

Arakin, V.D. (ed.) (2005). A Practical Course of English (7th Edition). Moscow: Humanitarian Publishing Centre VLADOS.

Haydarov, A. A. & Rasulov, Z. I. (2008). Modern Talking in English. A Handbook for Conversation classes. Bukhara: Bukhara State University.

Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. (2001). Council of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available online at: www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/Source/Framework_EN.pdf

Nagai, N., & O’Dwyer, F. (2011). The actual and potential impacts of the CEFR on language education in Japan. Synergies Europe, 2011, 141-152

Tarnanen, M., & Huhta, A. (2008). Interaction of Language policy and Assessment in Finland. Current Issues in Language Planning, 9(3), 262-281

Curriculum for Bachelor’s Degree English language teaching Programme. (2013). Tashkent: British Council, MHSSE.

Sample lesson plans for Curriculum for Bachelor’s Degree English language teaching Programme. (2013). Tashkent: British Council, MHSSE.

Hedge, T. (1993). Writing. Oxford: Oxford University Press

White, R. & Arndt, V. (1991). Process Writing. Harlow: Longman.

Pritchard, R., & R. L. Honeycutt. (2007). Best practices in implementing a process approach to teaching writing. In: Best practices in writing instruction. 28-49.

Hedge, T. (1993). Key concepts in ELT. ELT Journal, 47/3: 275 – 7.

Stoller, F.L. (1997). ‘Project work: A means to promote language and content’. Forum 35/4.

Fried-Booth, D. L. (2002). Project Work. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anthonv, E. (1963). Approach, method, technique. English language teaching, 63-7.

Blair, R. W. (ed.) (1982). Innovative Approaches to Language Teaching. Rowley, MA: Newbury House

Richards, J. & Rodgers, T.S. (1986). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crandall, J. J. (2000). Language teacher education. Annual review of applied linguistics, 20, 34-55.

Baratova, K. (2007). Working Syllabus for the Course Methods of teaching a foreign language. Karshi: Karshi State University. Available online at: http://uz.denemetr.com/docs/768/index-277394-1.html

Wallace, M. J. (1991). Training Foreign Language Teachers: A reflective approach. Cambridge University Press.

Schön, D. (1983).The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. London: Temple Smith.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential Learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Malderez, A. & Wedell, M. (2007). Teaching Teachers: Practices and processes. London: Continuum

Wright, T. & Bolitho, R. (2007). Trainer Development. available from: www.lulu.com

Woodward, T. (2003). Loop input. ELT Journal 57.3, 301–304.

Chastain, K. (1976). Developing Second Language Skills: Theory to practice. Rand McNally College Pub. Co.

Tomalin, B. & Stempleski, S. (2013). Cultural Awareness. Oxford University Press.

Pulverness, A. (1995). Cultural studies, British studies and EFL. Modern English Teacher, 4: 7-7.

Samandarov, Sh. (2009). Handbook for the English language course, Year 1. Namangan: Namangan State University.

Kramsch, C. J. (1983). Culture and constructs: Communicating attitudes and values in the foreign language classroom. Foreign Language Annals, 16 (6), 437-448.

Byram, M., & Zarate, G. (1994). Definitions, objectives and assessment of socio-cultural competence. Council of Europe

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Multilingual Matters.

McKay, S. L. (2002). Teaching English as an International Language: Rethinking goals and perspectives. NY: OUP.

Crystal, D (2003) English as a Global Language. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Graddol, D. (2005). English Next. British Council.

Pennycook, A. (1994). The Cultural Politics of English as an International Language. Longman, New York

Independent learning practice in higher education in Uzbekistan. Current situation and recommendations for further development. (2006). Tempus project final report. Tashkent: Westminster University in Tashkent. Available online at: http://www.wiut.uz/wp/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/Tempus%20Final%20%28Eng%29.pdf

Ochilov, Kh. & Allayarova, G. (2008). Handbook for Independent study in English language course Years 1-4. Navoi: Navoi State Pedagogical Institute (in Uzbek).

Holec, H. (1981). Autonomy and Foreign Language Learning. Oxford: Pergamon Press

Little, D. (1991). Learner Autonomy: Definitions, issues and problems. Authentik Language Learning Resources Limited.

Assessment specifications for the Curriculum for Bachelor’s Degree English language teaching Programme. (2013). Tashkent: British Council, MHSSE.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|