My French Learning Experience. A Diary Study

Simone Lira Calabrich, Brazil

Simone Calabrich, a Fulbright alumni, has a Master’s Degree in English Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics from King’s College London and a graduate certificate in TESOL from the University of Nebraska at Omaha. Her research interests are authenticity and use of technology in second language learning. E-mail: calabrich.simone@gmail.com

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

The Role of motivation and strategy use in my French learning experience

Conclusion

References

Some non-experienced language teachers often fail to understand the struggle their learners go through when attempting to master a foreign language, especially if said teachers are monolingual and have never attempted to learn a foreign language themselves. In this paper, I report my own short-term attempt, and struggle, to learn French whilst keeping a diary which I used to reflect on my own learning. I hope my account, which I relate to the relevant literature, can inspire other language teachers to pursue the same. This paper can be useful for non-experienced teachers wishing to immerse themselves in a language learning experience in order to better understand what goes on with their learners and be better equipped to guide them through the learning process. The two themes I focus on in this paper are motivation and strategy use in second language learning.

Studying foreign languages has always been a part of my adult life. At the age of 18, I embarked on a self-instructed journey to learn English and have never stopped studying it since then. Formally instructed exposure to other languages has followed subsequently but the same effort and dedication to achieve high proficiency levels was never applied again. When challenged by peers to engage in a second self-instructed language learning experience, I decided to select a language which, though sharing typological similarities with Portuguese, i.e. my first language (L1), had never appealed to me linguistically or culturally. In this paper, I will report my French learning experience, which I critically self-evaluated whilst keeping a language learning diary. My diary entries have clearly shown me that non-realistic expectations, unclear goals, lack of motivation, and little exposure to natural input were the main constituents of the initial stages of my French learning experience. Only after focusing on real life applicability did I start feeling motivated to continue learning. Furthermore, my persistence and extensive use of strategies helped me attain perceptible comprehension progress eventually.

I hope this account will encourage other second language (L2) teachers, especially the monolingual ones, to attempt learning a foreign language, either autodidactically or in a regular language course, and to keep a language learning diary, in order to better understand the struggle some of their language learners might be going through, especially in terms of how fluctuating motivation levels can be and a how a simple change of course can make the difference when a given strategy does not seem to be working.

Motivation

Motivation is widely accepted as one of the strongest predictors to second language-learning success, as proposed by Skehan (1989). Without motivation, it is believed learners are less likely to initiate and fully engage in L2 learning, which might consequently also hinder their progress and ultimate attainment. Upon scrutinizing my diary entries, I noticed that different issues recurrently investigated in motivation studies have emerged during my attempt to learn French.

During the social/psychological period of L2 motivation studies, Gardner and Lambert (in: Gardner 1985, Dörnyei 1990, Dörnyei 2005) proposed that individuals’ engagement in language learning could have an interpersonal/affective dimension, arising from a desire to socially and linguistically integrate in the target culture, or could have a practical/instrumental dimension, arising from a need to accomplish an academic or professional objective, for example. Dörnyei (1990) suggests that learners who demonstrate integrative motives are more likely to achieve higher levels of attainment in the target language.

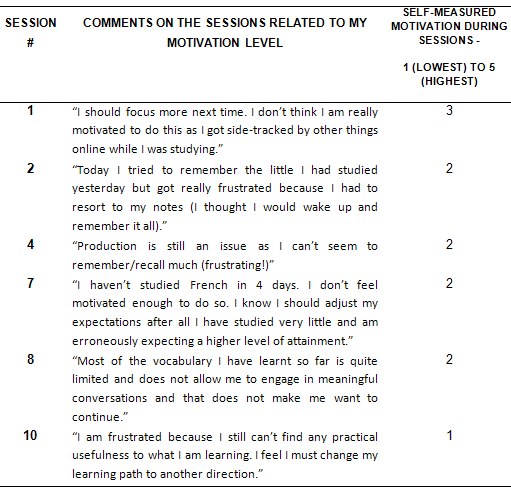

Never having had any interest in Francophone matters shaped my language learning experience as a solely instrumentally-oriented one at first. The first sessions were predominantly negative due to my initial lack of integrative interest in learning French along with my unrealistic expectations of producing language promptly and accurately, my poor memory skills, and my incapability to perceive (or perhaps to assign) meaningful relevance to what I was attempting to learn. Table 1 below presents some examples extracted from my diary entries showing my (de)motivation level at initial stages:

Table 1. Extracts from my French learning diary logs presenting examples of low motivation levels during initial sessions.

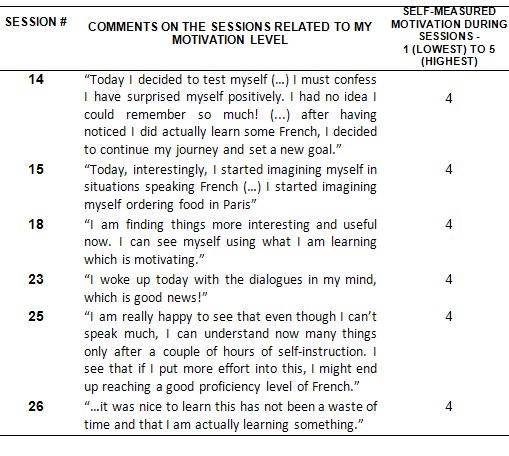

Selinker and Gass (2008), following a process-oriented approach in L2 motivation studies, refer to the non-static nature of motivation and how it can experience a restructuration over time depending upon different circumstances. A shift in my motivation level can be perceived following the undertaking of a self-assessment test (session #14) which indicated what learning strategies were more efficient and the progress I had made thus far. Table 2 shows instances of higher motivation levels and the emergence of a more positive attitude towards the learning endeavour after session #14:

Table 2. Extracts from my French learning diary logs presenting examples of high motivation levels following a successful self-assessment test.

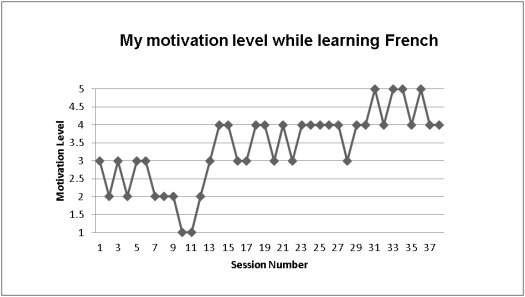

The shift in my motivation level (see Figure 1 below for a graph showing the development of my motivation self-measured over the sessions) derived from the progress realization, constitutes what Dörnyei (2005) identifies as the ‘motivational retrospection’ occurring during the postactional stage, which is the third stage of Dörnyei’s triple-phasic model of L2 motivation. According to Dörnyei’s cognitive–situated approach, students’ retrospective evaluation of their progress determines the subsequent steps individuals take in their learning path. The other two stages proposed by Dörnyei relate to the initial establishment of a goal (the preactional stage), and to the driving force to execute the activity while in pursuance of the goal despite the obstacles and distractions the individual might encounter (the actional stage).

Figure 1. Graph showing my self-measured motivation level while attempting to learn French.

According to Gardner (1985), establishing a goal, applying effort, having a determined desire and sustaining positive attitudes towards the endeavour are four significant aspects found in motivated learners with both instrumental and integrative orientations. In my French learning experience, I established three goals (in sessions #1, #14 and #26) and applied concomitant effort to achieve each one of them. Though positive attitudes only arose after session #14, the striving desire to overcome the linguistic hurdles was ever-present while in pursuance of my goals.

The importance of goal establishment was also emphasised by Dörnyei (1998), who supports the setting of proximal subgoals, as opposed to distal ones, such as ‘becoming fluent’, as those are more likely to assist learners in perceiving their ongoing progress or the need to modify their study plans.

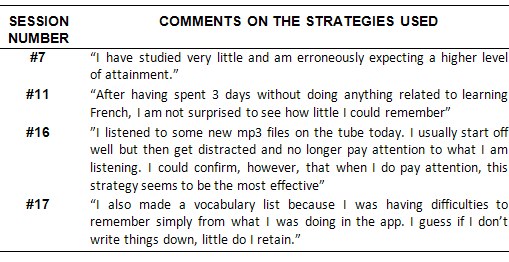

Having successfully learned and mastered an L2 through self-instruction previously contributed positively to this experience. I attempted to apply some of the same strategies I had used when learning English in order to verify which ones would be useful given that I was now learning an L2 I initially had no interest in. Due to my experience in learning foreign languages previously, whenever a strategy seemed ineffective in my attempt to learn French, I would ascribe its alleged failure to my inadequate usage of it or to my lack of focus and effort, rather than considering myself an incompetent learner and/or desisting from the task altogether (see Table 3 below for examples). The attribution theory, proposed by Weiner, supports the idea that individuals are more likely to succeed when they attribute their failures to extrinsic factors, such as strategy use, as opposed to underestimating their own cognitive capabilities (in: Dörnyei 2005). According to the attribution theory, future achievements are commonly dependent on individuals’ past experiences, which should shape learners’ motivational disposition accordingly.

Table 3. Extracts from my French learning diary showing examples of my insufficient effort when employing strategies.

My persistence and the strategic learning I deliberately undertook, demonstrated through my discerning use of a variety of resources available for L2 learning, such as language learning apps, YouTube videos, language learning websites, textbooks, audio recordings, along with an extensive use of authentic materials, such as French newspapers, children’s stories, songs, have contributed to the shift in my motivation level and its upkeep throughout this experience. In the next section, I will discuss the role played by my use of strategies while attempting to learn French.

Strategy Usage

Andrew D Cohen (2011a) defines language learner strategies as the thoughts and actions individuals consciously use when learning or attempting to use an L2, as well as when accomplishing any language-related task. Macaro (2001), conversely, draws attention to the inability demonstrated by some learners to articulate their strategy usage, defending the notion that the use of strategies is not necessarily performed consciously by learners. While acknowledging the controversy in this issue, Andrew D. Cohen (2011b) emphasizes that what makes learning strategic is the element of consciousness present in the strategy implementation. As an experienced language teacher, when attempting to learn a language myself, I pro-actively and consciously employ various strategies in order to facilitate and accelerate my learning. Some of the strategies used during my French learning experience had been employed previously in other L2 learning contexts while others were novel as I wanted to expand my repertoire of strategies.

The number of strategies available for L2 learning is virtually infinite as learners can creatively devise new strategies to suit their unique learning styles. In this paper, I will focus on the strategies classified according to the function they perform, the skill areas they can be applied to, and whether the strategy concerns the L2 learning process or L2 usage (in: Macaro 2001, Cohen and Weaver 2006, Cohen 2011) as these were the most salient in my experience.

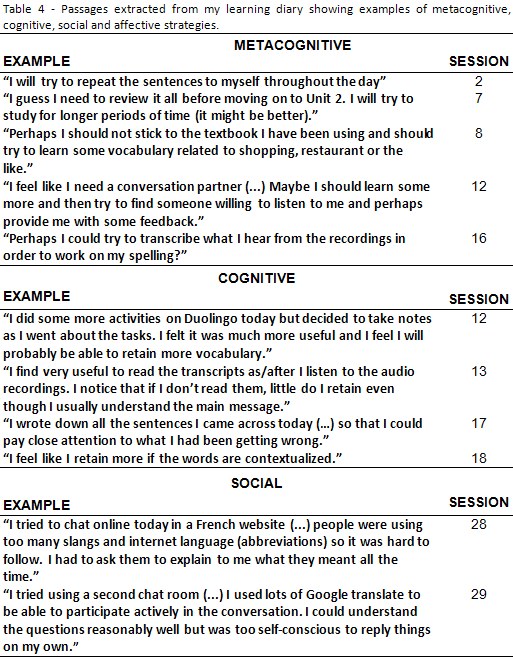

According to Macaro (2001), function-related strategies as proposed by O'Malley and Chamot (1990) can be summarized as follows:

- Metacognitive strategies refer to the strategies employed by learners to organize their language learning process, when planning what steps to take in their learning path, for example;

- Cognitive strategies refer to the strategies learners employ to deal with the mental processes of learning and using the target language resources, such as how to group and retain vocabulary;

- Social strategies refer to the strategies learners use to socially cope with communicative demands, as when learners search opportunities to engage in interpersonal communication with speakers of the target language and how they negotiate meaning to get their messages across;

- Affective strategies refer to the self-regulatory strategies employed by learners to deal with the crucial psychological aspects involved in L2 learning, such as anxiety or (de)motivation.

Instances of the four types of function-related strategies above can be found in my French learning experience, as demonstrated by the examples in Table 4 below:

Andrew D Cohen and Weaver (2006) point out that the greater the number of strategies individuals use, the more successful they are likely to be at L2 learning. Andrew D. Cohen (2011b) notes that research has shown that higher-proficiency learners make extensive usage of metacognitive strategies in particular.

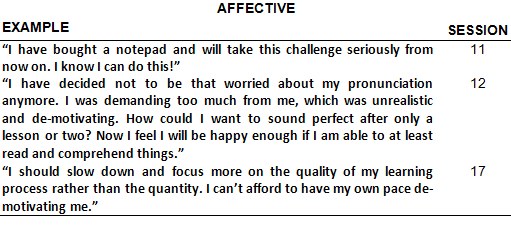

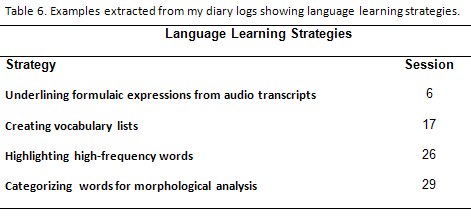

Language learner strategies can also be categorized according to the skill areas they can be applied to (Andrew D Cohen, 2011a). Various strategies can be employed in order to operationalise and facilitate the learning of productive areas (speaking and writing) and receptive areas (listening and reading). When coming across a challenging text, for example, learners may skim and scan it, activate their schematic knowledge by brainstorming themes related to the topic, and focus on paralinguistic elements in order to enhance their overall comprehension. In my French learning experience, several instances of skill-related strategies have appeared. Some examples can be found in Table 5 below:

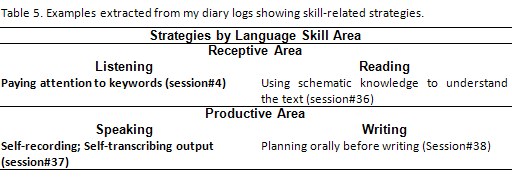

The third strategy classification concerns the conscious actions taken by learners to cope with the demands imposed by the L2 learning process itself or by the need to put the L2 into usage. Andrew D Cohen and Weaver (2006) define language learning strategies as the deliberate steps taken to approach and use the resources available to learn the L2, whereas language-use strategies as relating to the conscious processes used to compensate for the gaps occurring during the language use per se.

Table 6 shows some of the language learning strategies I employed in order to optimize my study routine and maximize my noticing of important patterns and structures in French:

Due to the solitary nature of my French learning experience, few were the strategies I employed for L2 production (see Table 5 above for examples). In communicative contexts, be it in the classroom or in real-life circumstances, L2 learners might use one of the following subsets of language-use strategies, as summarized by Andrew D Cohen and Weaver (2006):

- Retrieval strategies, i.e., conscious attempts to recall vocabulary learnt;

- Rehearsal strategies, i.e., the act of planning the utterances mentally before actually externalizing them;

- Communication strategies, i.e., creative and successful attempts to communicate despite having limited lexical knowledge and/or poor grasp of syntax;

- Cover strategies, i.e., conscious attempts to demonstrate a level which is higher than the learner’s actual level by making use of complex formulaic expressions or circumlocutions to impress interlocutors.

Having reflected on how strategic my L2 learning was and the extent to which motivational issues affected my progress whilst studying French will most certainly have a positive effect on my teaching practice. In the next section, I will present a conclusion of how this learning experience has significantly changed and reinforced some of pedagogical beliefs.

After having attempted to learn French in such an analytical manner, five aspects related to motivation studies and strategy usage in L2 learning have gained paramount importance to me, and I shall apply due effort to ensure their continuous implementation in my pedagogical practice. The five aspects are as follows:

- I consider now to be of the utmost importance to help learners find out what truly motivates them so that they can (re)direct their L2 study routine sensibly, eliminating de-motivating routes whilst pursuing a satisfying yet productive learning path. Csizér and Kormos (2009) note that an intrinsic interest in learning an L2 impacts greatly on learners’ success.

- When embarking on an L2 learning journey, I have noticed that a great number of students are unaware of how far they wish to go or the necessary steps they must take to achieve their target, which makes learners bring unrealistic expectations to their learning endeavour. This experience has showed me the importance of assisting students in establishing sub-goals (as opposed to the commonly unclear, distal and not viable “achieving ultimate proficiency” goal), since proximal goals provide learners with immediate incentive (Dörnyei, 1998) as they monitor learners’ progress continuously and are therefore more likely to maintain motivation at steady levels. The devising of a study plan should accompany the setting of sub-goals in order to enhance learners’ chances of success. When sub-goals are achieved at last, learners must decide whether that point will be their final destination in their L2 learning journey or just a stopover.

- The fact that I was learning things which did not afford me immediate real-life applicability in the initial stages of my French learning experience affected my motivation level significantly. My self-instructed experience has evidenced to me that only by carefully selecting the items to be taught will I be able to make my teaching a genuinely relevant learning experience to my students. Learners must be provided, not only with extensive comprehensible input, but mainly with meaningful input so that they can stay motivated until they are cognitively ready to produce output (since comprehension will inevitably precede production). If the teaching environment does not provide learners with the input they wish/need, it is paramount to encourage learners to obtain input themselves outside the classroom, as proposed by Ellis (2008). I, personally, consider voluntary exposure to the target language to be of the utmost importance for optimal L2 development.

- Although it is widely accepted that the teaching of strategies is not unanimously infallible in L2 pedagogy, learners must be introduced to a vast array of strategies for them to choose from so that they can draw on their learning styles wisely in order to maximize their outcomes. Manchon (2008) suggests that there is a fundamental correlation between strategy use and second language development. In Anderson’s (2008) view, the use of metacognition assists learners in making conscious decisions about what can be done to improve their learning. Having this in mind, I intend to enhance the teaching of metacognitive strategies in particular in order to help my students be in charge of their own learning, leading them to the autonomous use of all the educational and authentic resources readily available to empower them as active L2 users, rather than merely passive L2 learners.

- While it may be virtually impossible to tailor every single lesson to cater each learner’s need, as a teacher, I aim to vary the types of activities and approaches used in class on a regular basis to favour different learning styles, which, according to Oxford (2003), also helps learners develop beyond their comfort zone if they are encouraged to experiment with strategies to broaden their learning styles. Having experimented with different resources to learn French has enabled me to perceive that visual, auditory and kinaesthetic individuals must all be contemplated at some point in their L2 learning path.

This experience has emphasized the notion that students should be afforded opportunities to be able to control their language learning themselves in an educational setting where L2 instruction respects and matches learners’ linguistic needs and individual characteristics. Encouraging students to engage in L2 learning strategically and autonomously, and helping learners become less dependent on teachers should be a foremost objective.

Anderson, N. J. (2008). Metacognition and good language learners. Lessons from good language learners, 99-109.

Cohen, A. D. (2011a). Second language learner strategies. Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning, 2, 681-698.

Cohen, A. D. (2011b). Strategies in learning and using a second language (2nd ed. ed.). Harlow: Longman.

Cohen, A. D., & Weaver, S. J. (2006). Styles-and strategies-based instruction: A teachers’ guide: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

Csizér, K., & Kormos, J. (2009). Learning experiences, selves and motivated learning behaviour: A comparative analysis of structural models for Hungarian secondary and university learners of English. Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, 98-119.

Dörnyei, Z. (1990). Conceptualizing Motivation in Foreign‐Language Learning*. Language learning, 40(1), 45-78.

Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Language teaching, 31(03), 117-135.

Dornyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner : individual differences in second language acquisition. Mahwah, N.J.: L. Erlbaum.

Ellis, R. (2008). Principles of instructed second language acquisition. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics. Retrieved January, 9, 2009.

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning : the role of attitudes and motivation. London ; Baltimore, Md., U.S.A.: E. Arnold.

Macaro, E. (2001). Learning strategies in foreign and second language classrooms: Continuum London.

Manchon, R. M. (2008). Taking strategies to the foreign language classroom: Where are we now in theory and research? IRAL-International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 46(3), 221-243.

Oxford, R. L. (2003). Language learning styles and strategies: Mouton de Gruyter.

Selinker, L., & Gass, S. (2008). Second language acquisition: An introductory course: Taylor & Francis.

Skehan, P. (1989). Individual differences in second-language learning. London ; New York New York, NY: Routledge, Chapman and Hall.

Please check the English Improvement course at Pilgrims website.

|