Social Constructivism and Metacognition in an EFL Context: Inspecting the Contribution of Critical Thinking to EFL Learners’ Social Intelligence

Alireza Zaker, Iran

Alireza Zaker is currently a Ph.D. student of TEFL, Islamic Azad University (IAU), Science and Research Branch, Tehran, and an active member of the Young Researchers and Elites Club, IAU. Over the past few years, he has been teaching Advanced Research, Language Assessment, Language Teaching Methodology, Language Learning Theories, and Practical Teaching courses at IAU and some state universities in Iran. His specific areas of ELT research include Latent Variable Modeling, Language Assessment, Research Methodology, and Teacher Education.

Articles and Conference Presentations: http://srbiau.academia.edu/AlirezaZaker

E-mail: alireza.zaker@gmail.com

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Method

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

References

There is now a unanimous consensus that learning English as a Foreign Language (EFL) is inseparable from learners’ social and metacognitive capacities. Based on this premise and the profound significance of inspecting the way these internal capacities interact in a systematic way, this study investigated the relationship between EFL learners' Critical Thinking (CT) and Social Intelligence (SI). 174 randomly selected EFL learners, between the ages of 19 and 26 (Mage = 22 years), participated in this study. These EFL learners, who were being instructed chiefly through English, completed two questionnaires pertinent to CT and SI. The Spearman rank order coefficient of correlation was employed to analyze the collected data. The obtained results indicated that the relationship between EFL learners' CT and SI is significant and positive. Furthermore, running a linear regression revealed that CT can predict 46.4 percent of EFL learners’ SI. This was followed by calculating the prediction equation, making it possible to compute/predict the SI score of an individual using their CT score. Regarding the limitations and drawing upon the findings, the article concludes with some pedagogical implications and some avenues for future research.

According to the social constructivism theory of learning, a favored theory of learning, knowledge, including language competence, is actively constructed by the individual through a social and experiential process (Ashton-Hay, 2006; Sprenger & Wadt, 2008). Therefore, the factors affecting English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners’ social performance are of paramount importance when it comes to promoting language learning. Some of these factors are the psychological factors and peculiarities of learners which are believed to play a major role in materializing the desired pedagogical goals in a language learning context (Lightbown & Spada, 2013; Nosratinia & Zaker, 2014, 2015; O' Donnell, Reeve, & Smith, 2012; Zaker, 2013, 2015). It is believed that these internal factors can predict learners’ motivation and social performance (Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2002). However, the literature does not provide many examples of such a focus.

Social Intelligence (SI) is one of the significant factors in predicting individuals’ social performance and communication (Aminpoor, 2013; Dong, Koper, & Collaço, 2008). As Goleman (2006) states, Edward Thorndike has introduced the basic assumptions of SI in 1920. Ford and Tisak (1983) defined SI as “one’s ability to accomplish relevant objectives in specific social settings” (p. 197). Moreover, Marlowe (1986) defined SI as “the ability to understand the feelings, thoughts, and behaviors of persons, including oneself, in interpersonal situations and to act appropriately upon that understanding” (p. 52). According to Goleman (2006) SI consists of two main components: social awareness and social facility. In his view, social awareness is “what we sense about others” and social facility is “what we then do with that awareness” (Goleman, 2006, p. 84).

According to Goleman (2006), social awareness has four major aspects, namely primal empathy, attunement, empathic accuracy, and social cognition. Primal empathy has been defined as the ability to sense others’ nonverbal emotional signals. Attunement is concerned about being focused on someone and actively listening to that person. Empathic accuracy, a cognitive capacity, is based on primal empathy and is about the understanding of other person’s current experience. Social cognition, the last component, is about the knowledge of the way the social world works, for instance, the rules of etiquette, resolving social quandaries, and deciphering social signals (Goleman, 2006).

Social facility, the second component of SI (Goleman, 2006), employs the social awareness and attempts to create smooth and effective interactions with others. Goleman (2006) states that social facility has four components: synchrony, self-presentation, influence, and concern. Synchrony is about communicating through nonverbal tools. Self-presentation is the capacity to present oneself in a favorable way, e.g. making a good impression. Influence is the capacity to form the consequence of interaction in a constructive way, and, finally, concern is appreciating another individual’s needs and taking appropriate action (Goleman, 2006).

SI is believed to be affected by both internal and external factors (Taylor, 1990). Moreover, Weis and Süb (2007) state that SI is affected by individuals’ cognitive and metacognitive abilities. This is why inspecting the way SI is associated with the acknowledged and studied mental factors becomes reasonable. Critical Thinking (CT) is one of these factors which is attracting increasing attention in the domain of Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL). In fact, CT is believed to be one of the metacognitive factors which exert enormous impact on the process of learning EFL (Connolly, 2000; Fahim & Zaker, 2014; Kabilan, 2000; Nosratinia & Zaker, 2013, 2015). It has been stated that in order to become proficient in a language, language learners should employ CT through the target language (Kabilan, 2000). Moreover, Dam and Volman (2004) argue that CT is a major factor in determining and predicting one’s desire to socialize and interact with others in different contexts, including language learning contexts.

Socrates, being recognized as the pioneer of CT tradition, favored reflectively questioning commonly held beliefs and assumptions; moreover, he favored the idea that reasonable and logical beliefs should be separated from beliefs not supported by evidence or rational basis (Cosgrove, 2009). As stated by Astleitner (2002), CT "is a purposeful, self-regulatory judgement which results in interpretation, analysis evaluation, and inference, as well as explanations of evidential, conceptual, methodological or contextual considerations upon which the judgement is based" (p. 53). It has been stated that CT would enable an individual to scrutinize and explore an issue from different standpoints (Willingham, 2008), and numerous studies have provided empirical evidence that teaching CT skills would facilitate language learning (Chapple & Curtis, 2000).

Based on the abovementioned premises, it can be argued, although theoretically, that both SI and CT can facilitate the process of language learning. However, there is no evidence if these factors are systematically associated or not. It seems that that the answer to this question can provide EFL teachers, learners, and curriculum developers with the capacity to promote or even manipulate either of SI and CT, based on the possibilities and characteristics of the teaching context, in order to encourage the other one, being SI or CT, and ultimately promote language learning. Moreover, the answer to this question can enhance our level of understanding of these psychological constructs. Motivated by these assumptions, this study attempts to systematically study the way EFL learners’ SI and CT are associated through answering the following research questions:

Q1: Is there any significant relationship between EFL learners' critical thinking and social intelligence?

Q2: How much can EFL learners' critical thinking predict their social intelligence?

Participants

The participants in this research consisted of undergraduate EFL learners majoring in English Translation and TEFL at the Islamic Azad University, South Tehran Branch. In these full-time undergraduate courses, English is the main medium of instruction; however, occasional use of learners’ L1 (Persian) is tolerated. From the abovementioned population, 174 male and female EFL learners (120 females, 69%, and 54 males, 31%), between the ages of 19 and 26 (Mage = 22 years) were selected via cluster random sampling.

Instruments

Two instruments were employed in order to collect the data, representing participants’ CT and SI levels; they were:

- The critical thinking questionnaire, developed by Honey (2000); and

- The social intelligence questionnaire, developed by Safarinia, Solgi, and Tavakkoli (2011).

Critical Thinking Questionnaire

The Critical Thinking Questionnaire intends to explore what a person might or might not do when thinking critically about a subject. Developed by Honey (2000), the questionnaire aims at evaluating the three main skills of comprehension, analysis, and evaluation of the participants. This questionnaire is a Likert-type questionnaire with 30 items which allows researchers to investigate learners' ability in note-taking, summarizing, questioning, paraphrasing, researching, inferencing, discussing, classifying and outlining, comparing and contrasting, distinguishing, synthesizing, and inductive and deductive reasoning.

The participants were asked to rate the frequency of each category they use on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from never (1 point), seldom (2 points), sometimes (3 points), often (4 points), to always (5 points). The participants' final scores are calculated by adding up the numbers of the scores. The ultimate score is computed in the possible range of 30 to150. The participants were allocated 20 minutes to complete the questionnaire.

In this study, the Persian version of this questionnaire was employed which was translated and validated by Naeini (2005). In a study conducted by Nosratinia and Zaker (2015) on EFL learners, the reliability of this questionnaire was estimated to be 0.79 using Cronbach's alpha coefficient. In this study, the reliability of CT questionnaire was estimated to be 0.81 using Cronbach's alpha coefficient which demonstrated a fair degree of reliability.

Social Intelligence Questionnaire

Originally developed by Tet in 2008 (as cited in Safarinia et al., 2011), this questionnaire is designed to estimate the degree of SI among individuals. This instrument attempts to explore different aspects of SI by asking questions pertinent to the ability to understand the feelings, thoughts, and behaviors in interpersonal situations and the way the individual would act upon that understanding.

This questionnaire consists of 45 yes-no questions. The correct answer receives 1 point and the wrong answer will get no points. A number of the items are reverse-scored items; therefore, the correct answers include both yes and no answers. The language of the original version of this questionnaire is English; however, in order to make sure that language proficiency does not affect the answers, in this study the Persian version of this instrument was employed.

The Persian version of the test has been translated and validated by Safarinia et al. (2011). Through the process of validation, Safarnia et al. (2011) have realized that 9 items should be excluded from the Persian version of the test. Accordingly, the Persian test has 36 items, and the total score can range from 0 to 36. The participants were allocated 15 minutes to complete the questionnaire.

Safarnia et al., (2008) reported a reliability index of 0.78 for this instrument estimated by Cronbach's alpha coefficient. In this study, the reliability of SI questionnaire was estimated to be 0.76 using Cronbach's alpha coefficient which demonstrated a fair degree of reliability.

Procedure

In order to address the research questions of this descriptive research, certain procedures were pursued. To begin with, the researcher obtained a formal approval for carrying out the research where the data were to be collected (see participants). Based on the nature of correlational studies, no criterion was adopted to establish homogeneity among the participants. The data collection phase began with codifying three available classes for every session of questionnaire administration. Thence, one of these three classes was chosen randomly for administering the questionnaires, and the other two classes were excluded from the study. This selection procedure followed the principles of cluster sampling which is believed to increase the validity and generalizability of the findings (Best & Kahn, 2006; Springer, 2010).

In each selected class, the EFL learners were initially briefed on the objectives of this study, and completing the questionnaires was not obligatory. They were also assured of the confidentiality of the information they provide. The participants were, thence, briefed on how to complete the questionnaires in Persian. The order of administering the two questionnaires was randomized by the researcher with the aim of controlling the order impact exerted on the completion process and validity of the data.

After this randomization, the two questionnaires were distributed among the participants, and the filling out process was observed to make sure the participants could understand the questions easily. 35 minutes was the time devoted for completing the questionnaires. After collecting the questionnaires, they were scored and the total scores of the questionnaires comprised the data for the statistical analyses elaborated below. Before moving to the next section, it should be mentioned that, initially, 250 individuals received the questionnaires; nevertheless, only 174 sets of the questionnaires were usable, and the rest of them were excluded from the data due to the incompleteness of answers and other similar usability issues.

Preliminary analyses

Before answering the research questions of this descriptive study (Springer, 2010; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007), it was needed to check a number of assumptions and perform some preliminary analyses. These analyses would determine the legitimacy of running the analysis along with the type of statistical techniques, i.e. parametric or non-parametric. To begin with, the assumptions of interval data and independence of subjects (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007) were already met as the present data were measured on an interval scale and the subjects were independent of one another. In addition, it was needed to check some other significant assumptions through exploring the features of the data. These assumptions, according to Tabachnick and Fidell (2007), are:

- Linear relation between each pair of variables,

- Homoscedasticity, and

- Normality of the distribution of the scores.

The following sections will check the three abovementioned assumptions which are pertinent to the first research question of the study. However, as the legitimacy of addressing the second research question is dependent on the answer given to the first research question, the preliminary analyses pertinent to the second research question are reported after addressing the first research question.

Linear relation between each pair of variables and homoscedasticity

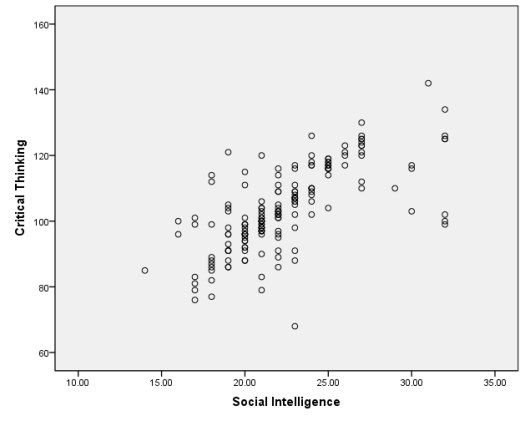

In order to check the linearity of relations, it was needed to visually inspect the data by creating a scatter plot (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Scatterplot of critical thinking and social intelligence

As depicted in Figure 1, there was no kind of non-linear relationship between the scores of the two variables, such as a U-shaped or curvilinear distribution. Consequently, the linearity of relation was confirmed. Moreover, the distributions were not funnel shape, i.e. wide at one end and narrow at the other; therefore, the assumption of homoscedasticity was met.

Normality of the distributions

In order to check the normality of the distributions, the descriptive statistics of the data were obtained which are reported thoroughly in the next sections.

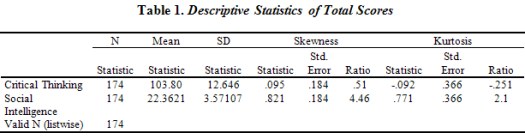

Descriptive statistics of the scores

The descriptive statistics pertinent the scores on the two instruments of the research appear below, in Table 1.

As reported in Table 1, the distributions of CT and SI scores were not normal as almost all the skewness ratios and the kurtosis ratios (except one case) did not fall within the range of -1.96 and +1.96. Moreover, the inspection of the actual shapes of the distributions through checking the histograms of distributions did not adequately support the normality of the scores’ distributions.

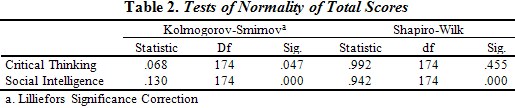

Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test of Normality

In order to assess the normality of the distribution of the scores further, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was run, results of which are presented in Table 2.

As presented in Table 2, the Sig. values are less than .05. Therefore, it is suggested that the assumption of normality is violated.

The first research question

As stated earlier, the first driving force behind conducting this study was to systematically investigate the relationship between EFL learners’ CT and SI. Consequently, the subsequent question was posed as the first research question of this study:

Q1: Is there any significant relationship between EFL learners’ critical thinking and social intelligence?

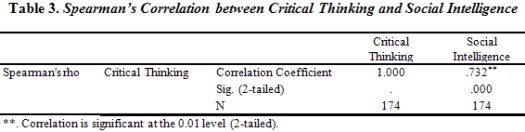

According to the results of the preliminary analyses reported above, it was not legitimate to employ a parametric statistical technique to address this research question. As a result, the data were analyzed using the Spearman rank order coefficient of correlation. Table 3 shows the result of this analysis.

The obtained results showed a significant and positive correlation between the two variables, ρ = .73, n = 174, p < .01, and high levels of CT were associated with high levels of SI. This signified a large effect size supplemented by a very small confidence interval (0.653 – 0.792).

Preliminary analyses pertinent to the second research question

As the answer to the first research question confirmed the existence of a positive, significant, and meaningful relationship (Henning, 1987) between CT and SI, it was legitimate to consider the second research question. The second research question of this study was answered through running a linear regression analysis. However, there are a number of assumptions which had to be checked before performing the analysis. According to Tabachnick and Fidell (2007), these assumptions are:

- Sample size

- Multicollinearity

- Normality

- Outliers

Sample size

There are different ideas about the legitimate number of participants needed for running a regression. Among these, Tabachnick and Fidell’s (2007) criterion is highly recommended by many experts. Tabachnick and Fidell (2007) proposed a formula for calculating sample size requirements, taking into account the number of independent variables: N > 50 + 8m (where m = number of independent variables). In this analysis, there was one independent variable, being CT, calling for a sample including more than 58 participants. Therefore, based on having a sample including 174 cases, this assumption was met.

Multicollinearity

Multicollinearity deals with the relationship among the independent variables. More specifically, multicollinearity exists when the independent variables are highly correlated (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). However, as there was only one independent variable in this analysis, this assumption was not checked.

Normality

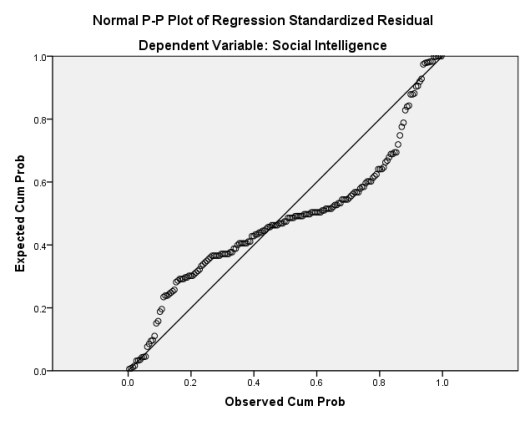

One of the employed techniques for checking normality in a regression analysis is inspecting the Normal P-P Plot. Here, we hope that the points lie in a reasonably straight diagonal line from bottom left to top right. Figure 2 presents the Normal P-P Plot of regression standardized residuals.

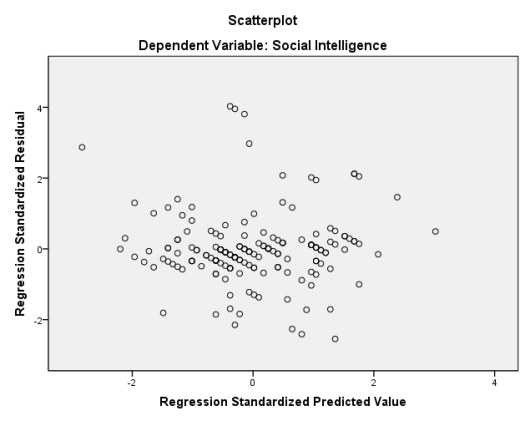

The inspection of Figure 2 suggests some deviation from normality. However, the scatterplot of standardized residuals (Figure 3) showed that residuals were roughly rectangularly distributed, with most of the scores concentrated in the center.

As observed in Figure 3, there was no clear or systematic pattern to the residuals.

Outliers

The presence of outliers can be detected from the scatter plot of standardized residuals (Figure 3). According to Tabachnick and Fidell (2007), outliers are cases that have a standardized residual of more than 3.3 or less than -3.3. The inspection of Figure 3 suggested that there are some cases which exhibit the characteristics of outliers. However, in large samples, it is common to find a number of outlying residuals (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Therefore, after meeting the assumptions of running a regression analysis, it seemed systematically justified to address the second research question, reported below.

The second research question

After inspecting a significant relationship between CT and SI and inspecting the possibility of running a regression analysis, the researcher attempted to answer the second research question of the study, stated below:

Q2: How much can EFL learners' critical thinking predict their social intelligence?

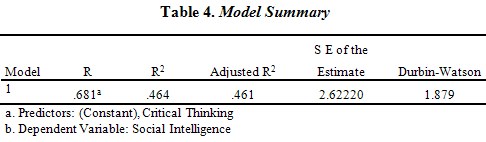

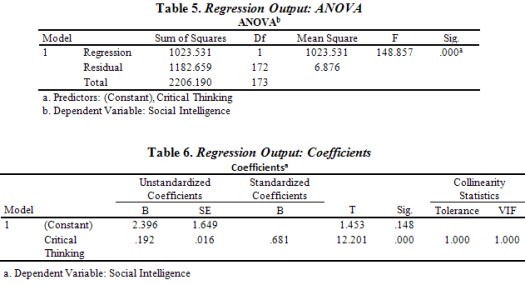

A linear regression analysis was run to probe how much EFL learners' CT can predict their SI. Based on the results displayed in Table 4, it was concluded that CT can predict 46.4 percent of EFL learners’ SI (R = .681, R2 = .464). The adjusted R2 value was .461. The difference between the observed and adjusted R2 (.464 - .461 = .003) indicated that the observed predictive power had .003 (.03 percent) difference with the population index. Based on these results it can be concluded that the regression model enjoyed the generalizability power. Moreover, the Durbin-Watson index of 1.879 indicated that the assumption of independence of errors was met.

Table 5 examines the statistical significance of the regression model. The results (F (1, 172) = 148.85, p < .05, eta squared = .86 representing a medium to large effect size) indicated that the CT significantly predicted SI.

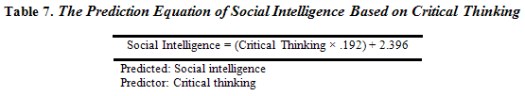

Table 6 displays the regression coefficients which can be used to formulate the regression equation, as shown below (Formula 1):

Social Intelligence = (Critical Thinking × .192) + 2.396 (1)

The beta value of .192 indicated that one full standard deviation change in CT resulted in .192 standard deviation change in SI. The results of the t-test (t = 12.201, p < .05) indicated that the beta value of .681 enjoyed statistical significance. The other two important statistics, i.e. Tolerance and VIF (variance inflation rate), indicated that the assumption of lack of collinearity, too high correlation among all variables, was met. Tolerance values less than .10 and VIF values higher than 10 are problematic.

As stated earlier, this study was an attempt to scrutinize the association between EFL learners’ CT and SI. The analysis of the data provided a number of findings which reveal the nature of these variables, especially in this context. Each of these findings will be discussed in this section. To begin with, the answer to the first research question which was provided through a correlational analysis provides a systematic understanding about the way CT and SI are associated.

The constructivist view of language learning favors an active and social process of learning (Ashton-Hay, 2006; Sprenger & Wadt, 2008). Many factors affect this social ability, measured here by SI (Aminpoor 2013; Dong, Koper, & Collaço, 2008). According to Weis and Süb (2007), SI is affected by individuals’ cognitive and metacognitive abilities, measured here by CT. A myriad of studies have attempted to study CT from different perspectives (Fahim & Zaker, 2014; Kabilan, 2000; Nosratinia & Zaker, 2014, 2015); however, no systematic attempt has studied the way CT and SI are associated.

The first research question of this study attempted to systematically inspect the way CT and SI are associated. As the assumptions of employing parametric statistical techniques were not met, this correlational analysis was carried out by using the Spearman rank order coefficient of correlation. The obtained results showed a positive, significant, and meaningful correlation between CT and SI, ρ = .73, n = 174, p < .05, and high levels of CT were associated with high levels of SI, signifying a large effect size supplemented by a very small confidence interval (0.653 – 0.792). This finding seems to systematically confirm Wilson’s (2010) argument in which social and reflective capacities are assumed related. This finding also provides support for Treverton’s (as cited in Moore, 2007) idea about the significance of CT in social performance and learning.

After observing this significant relationship between CT and SI, it seemed reasonable to ask about the exact amount of CT’s contribution to SI. Although the answer to this question might not provide a fixed equation for all learning contexts (Best & Kahn, 2006; Springer, 2010), it can provide a more tangible idea about the way CT affects social performance and potential social learning. Answering this question required running a linear regression analysis which was run after checking the preliminary assumptions.

The results of the regression analysis indicated that CT can predict 46.4 percent of EFL learners’ SI (R = .681, R2 = .464). Moreover, the researcher calculated the prediction equation in which the SI score of an individual can be calculated using their CT score. This formula is presented below:

Although more studies are needed to confirm these findings (Best & Kahn, 2006), the abovementioned points strongly favor the significant role of CT in EFL learners’ social performance, and as a result, language learning process. Moreover, as language learning is the main concern in our field, it would be reasonable, even necessary, to inspect the way CT and SI, as two major mental elements (Dong et al., 2008; Nosratinia & Zaker, 2014, 2015), contribute to language learning; this, perhaps, can be achieved through including CT, SI, and different language skills as the variables of the studies.

The process of learning a second language is believed, unanimously, to be a social and cognitive process (Wilson, 2010). This perspective seems to be contemporaneous with the learner-centered focus on learning in which learners are given an active role in developing language proficiency (Bell, 2003; Kumaravadivelu, 2008, 2012; Nosratinia & Zaker, 2014, 2015). This autonomous capacity among learners is believed to be influenced by the amount of participation in the learning context and social context, as well as the metacognitive capacity to approach learning in a reflective manner.

The abovementioned concerns seem to have in common with the foundational premises of social constructivism in which learning is assumed to be an active, reflective, and social process (Fosnot, 2006; Lunenburg, 2011). In the school of constructivism, it is believed that learners “actively construct their knowledge, rather than simply absorbing ideas spoken to them by teachers” (Lunenburg, 2011, p. 3). As a result, it is a valid concern to inspect the way through which, EFL learners’ reflective and social capacities can be developed. This study estimated EFL learners’ social ability through SI as a valid representative of social competence (Aminpoor 2013; Dong, Koper, & Collaço, 2008). According to Weis and Süb (2007), SI is affected by individuals’ cognitive and metacognitive abilities, estimated here through CT as a valid representative of metacognitive capacities (Fahim & Zaker, 2014; Nosratinia & Zaker, 2014, 2015; O' Donnell, Reeve, & Smith, 2012).

So far, no systematic attempt has studied the way CT and SI are associated; accordingly, this descriptive study attempted to study the way CT and SI are correlated among EFL learners. One further goal of this study was to calculate and report the share of CT in predicting SI, hoping to provide a clearer understanding about the way CT and SI are related. Both male and female EFL learners participated in this study. The results of the data analysis process indicated that a significant and positive correlation exists between CT and SI. Moreover, it was observed that CT can predict 46.4 percent of EFL learners’ SI, and the SI scores can be calculated by employing this formula: Social Intelligence = (Critical Thinking × .192) + 2.396.

The main implication of this finding seems to be the importance of encouraging CT among EFL learners. EFL teachers can employ different techniques to achieve this goal, ranging all the way from implicit support to explicit instruction. For instance, EFL teachers can explicitly acquaint EFL learners with the basic principles and components of CT (i.e. problem identification, context definition, listing choices, options analysis, listing reasons explicitly, and self-correction; Nosratinia & Zaker, 2014).

EFL teachers can also encourage CT through providing positive feedback and encouragement when CT is observed in learners’ behavior (Karagiorgi & Symeou, 2005). However, this calls for possessing a reasonable degree of familiarity with this construct on the side of the teacher. Moreover, EFL learners should be informed about how CT can assist and promote learning different language skills.

EFL teachers should endeavor to integrate CT–oriented activities with other learning tasks and activities in the classroom. On the other hand, creating an atmosphere of valuing CT and learners’ responsibility for learning can be highly conducive to learners’ learning quality and quantity (Nosratinia & Zaker, 2014). Teachers should plan the instruction in a way that encourages the mental capacities required to operate autonomously. In a nutshell, EFL teachers should encourage personal and social consciousness in the learners and attempt “to enable students to become the architects of their own education so that they can invent themselves during the course of their lives” (Eisner, 2003, p. 652).

Considering the materials employed for EFL/ESL classes, the findings of the present study can contribute to syllabus designers’ understanding about the way CT can assist communicative capacities and language learning. According to Dam and Volman (2004, p. 375), “learning by participation always involves reflection”. Therefore, EFL syllabi should put more attention to interactive activities and learners’ active role. Furthermore, an EFL syllabus can enhance learners’ CT through addressing epistemological beliefs, promoting active learning, and following a problem- based approach (Dam & Volman, 2004). This way, and based on the results obtained in the present study, EFL learners’ SI and learning can be facilitated.

Based on the obtained result and the depicted background of the study, it seems reasonable to argue that achievement and diagnostic EFL/ESL tests which embody CT and SI can equip language teachers with a more informed and comprehensive understanding of EFL learners’ cognitive, metacognitive, and social capacities. As a result, the chance of making wiser and more appropriate pedagogical decisions on the side of EFL teachers would substantially increase (Nosratinia & Zaker, 2014). Similarly, if CT and SI are included in prognostic tests, e.g. placement tests, the possibility of establishing the link between learners’ CT and SI levels and the language course in which they are enrolled would significantly raise.

Considering the characteristics and limitations of this study, e.g. the limited focus of the study which included only two variables, the unexplored interaction between the variables of this study and language skills, the unexplored interaction between the variables of this study and other mental factors, the characteristics of the participants, and the characteristics of the data collection process, there are many avenues for further research. For instance, other studies can explore the interaction between the variables of this study and other cognitive, metacognitive, and personality factors. It is also suggested to study the way CT and SI interact with language skills among EFL learners. Another option would be conducting the same study among other age groups. Moreover, a study in which there are equal numbers of male and female participants would remove gender as a potential confound. Finally, in order to increase the generalizability and reliability of the results, the quality of the employed data can be enhanced by employing qualitative instruments like open-ended questions, interviews, and observation.

Aminpoor, H. (2013). Relationship between social intelligence and happiness in Payame Noor University students. Annals of Biological Research, 4(5), 165-168.

Ashton-Hay, S. (2006) Constructivism and powerful learning environments:Create your own! Paper presented at the 9th International English Language Teaching Convention: The Fusion of Theory and Practice, Middle Eastern Technical University, Ankara, Turkey. Retrieved May 22, 2015, from http://eprints.qut.edu.au/17285/1/17285.pdf

Astleitner, H. (2002). Teaching critical thinking online. Journal of instructional psychology, 29 (2), 53-77.

Bell, D. M. (2003). Method and postmethod: Are they really so incompatible? TESOL Quarterly, 37 (2), 325-336. doi: 0.2307/3588507

Best, J. W., & Kahn, J. V. (2006). Research in education (10th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapple, L., & Curtis, A. (2000). Content-based instruction in Hong Kong: Student responses to film. System, 28 (3), 419-433. doi: 10.1016/S0346-251X(00)00021-X

Connolly, M. (2000). What we think we know about critical thinking. CELE Journal, 8, Retrieved April 20, 2003, from http://www.asiau.ac.jp/english/cele/articles/Connolly_Critical-Thinking.htm

Cosgrove, R. (2009). Critical thinking in the Oxford tutorial (Master's thesis, University of Oxford) Retrieved from http://www.criticalthinking.org/files/ Critical%20Thinking%20in%20the%20Oxford%20Tutorial.pdf

Dam, G. T. M., & M., Volman (2004). Critical thinking as a citizenship competence: teaching strategies. Learning and Instruction, 14, 359–379. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2004.01.005

Dong, Q., Koper, R. J., & Collaço, C. M (2008). Social intelligence, self-esteem, and intercultural communication sensitivity. Intercultural Communication Studies, 17(2), 162-172.

Eisner, E. W. (2003). Questionable assumptions about schooling. Phi Delta Kappan, 84(9), 648-657.

Fahim, M., & Zaker, A. (2014). EFL learners’ creativity and critical thinking: Are they associated? Humanising Language Teaching, 16 (3). Retrieved from http://old.hltmag.co.uk/jun14/mart01.htm

Ford, M. E., & Tisak, M. S. (1983). A further search for social intelligence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 75(2), 196-206. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.75.2.196

Fosnot, C.T. (2006). Constructivism: Theory, perspectives, and practice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Goleman, D. (2006). Social intelligence: The new science of human relationships. New York: Bantam Books.

Henning, G. (1987). A guide to language testing: Development, evaluation, research. Cambridge, MA: Newbury House.

Kabilan, M. K. (2000). Creative and critical thinking in language classrooms. The Internet TESL Journal, 6 (6). Retrieved November 21, 2005 from http://itselj.org/Techniques/Kabilian- CriticalThinking.html

Karagiorgi, Y., & Symeou, L. (2005). Translating constructivism into instructional design: Potential and limitations. Educational Technology & Society, 8(1), 17-27.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2008). Understanding language teaching: From method to postmethod. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2012). Language teacher education for a global society: A modular model for knowing, analyzing, recognizing, doing, and seeing. New York: Routledge.

Lightbown, P., & Spada, N. (2013). How languages are learned (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lunenburg, F. C. (2011). Critical thinking and constructivism: Techniques for improving student achievement. National Forum of Teacher Education Journal, 21(3), 1-9.

Marlowe, H. A. (1986). Social intelligence: Evidence for multidimensionality and construct independence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 78(1), 52-58. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.78.1.52

Moore, D. T. (2007). Critical thinking and intelligence analysis. Washington, DC: National Defense Intelligence College. doi: 10.1037/e509522010-001

Naeini, J. (2005). The effects of collaborative learning on critical thinking of Iranian EFL learners (Unpublished master's thesis). Islamic Azad University at Central Tehran, Iran.

Nosratinia, M., & Zaker, A. (2013, August). Autonomous learning and critical thinking: Inspecting the association among EFL learners. Paper presented at the First National Conference on Teaching English, Literature, and Translation, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran. Retrieved from http://www.civilica.com/Paper-TELT01-TELT01_226.html

Nosratinia, M., & Zaker, A. (2014). Metacognitive attributes and liberated progress: The association among second language learners’ critical thinking, creativity, and autonomy. SAGE Open, 4(3), 1-10. doi: 10.1177/2158244014547178

Nosratinia, M., & Zaker, A. (2015). Boosting autonomous foreign language learning: Scrutinizing the role of creativity, critical thinking, and vocabulary learning strategies. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 4(4), 86-97. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.4p.86

O' Donnell, A., Reeve, J., & Smith, J. (2012). Educational psychology: Reflection for action (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68-78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). An overview of self-determination theory. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 3-33). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Safarinia, M., Solgi, Z., & Tavakkoli, S. (2011). Investigating the validity and reliability of the Social Intelligence Questionnaire among university students in Kermanshah. Social Psychology Research, 1(3), 57-70.

Sprenger, T. M., & Wadt, M. P. S. (2008). Autonomy development and the classroom: Reviewing a course syllabus. DELTA, 24, 551-576. doi: 10.1590/S0102-44502008000300009

Springer, K. (2010) Educational research: A contextual approach. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics. Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc.

Taylor, E. H. (1990). The assessment of social intelligence. Psychotherapy, 27(3), 445-457. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.27.3.445

Weis, S. & Süb, H. (2007). Reviving the search for social intelligence—A multitrait- multimethod study of its structure and construct validity. Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 3-14. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.027

Willingham, D, T. (2008). Critical thinking: Why is it so hard to teach? Arts Education Policy Review, 109 (4), 21-29. doi: 10.3200/AEPR.109.4.21-32

Wilson, B. G. (2010). Constructivism in practical and historical context. Retrieved May 22, 2015, from http://carbon.ucdenver.edu/~bwilson/Constructivism.pdf

Zaker, A. (2013). The relationship among EFL learners’ creativity, critical thinking, and autonomy (Unpublished master’s thesis). Islamic Azad University at Central Tehran, Iran.

Zaker, A. (2015). EFL learners’ language learning strategies and autonomous learning: Which one is a better predictor of L2 skills? Journal of Applied Linguistics-Dubai, 1(1), 27-39.

Please check the English Improvement course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Secondary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|