Systemic Approaches to Units of Editing

Shibu Simon, India

Shibu Simon teaches at India’s ‘National Defence Academy’ at Pune under the Ministry of Defence. He has introduced the genre ‘Editing Studies’ in English and has published seven books on ELT and is an active researcher in TESOL. E-mail: ambatshibu@rediffmail.com.

Menu

Introduction

Editing units and editing strategies

Systemic analysis of editing units

Conclusion

Notes

References

For any science, one of the essential and often the most controversial preliminary steps is defining the units with which to operate1. Because of the difficulty experienced in analysing the complex process of editing, there has not been much headway in defining the unit of editing. It is generally thought of as the linguistic unit (Shuttleworth and Cowie 1997: 192) which the editor uses when editing and at which level the source text (ST) is recodified into target text (TT). Various units have been proposed as units of editing – word, phrase, clause, sentence, paragraph or the text itself. Newmark (1988: 66-67) even proposed that “all lengths of language” have the potential to function so “at different moments and also simultaneously.” It may seem that editors often work at the level of sentence or paragraph, but they cannot afford to neglect the function of the whole text, and references to its inter-textuality2 and extra-textual3 features.

In general, editing units are linked to editing strategies. To a great extent the smaller the units, the greater the dependence on ‘grammatical’ and ‘stylistic’ editing strategies while ‘structural’ editing strategy aims at capturing the sense of longer stretches of language.

Grammatical editing is editing at the primary level. Here the editor is basically engaged in checking the text for errors in relation to the rules of grammar and conventions of its language use. Besides, it checks the text for such basic submission requirements, prescribed by the editorial board, as its length, specifications related to font, margins, titles, references, diagrammatical representations, paragraph alignment, spacing and indentation. Source text interference/presence will be the highest in this kind of editing since the editor more or less retains the form of the source text along with its lexical choices and syntactic patterns as long as the edited text’s comprehensibility is not compromised. Consequently, editor interference will be the lowest since grammatical editing doesn’t offer much scope for editor interpretation4 and negotiation5. However, domestication6 will be a casualty if the ST was originally written by an author for whom source language (SL) was a foreign tongue and with whose culture the writer has limited familiarity.

Stylistic editing includes grammatical editing and is considered as an editing strategy at an advanced level. At this stage, the editors are primarily concerned with the stylistic options available to them in the place of the lexical and syntactic choices exercised by the ST writer. Besides improving cohesion and reading comprehension, stylistic editing strategy enhances domestication by focussing on the general style and force of the native tongue. Increased editor presence correspondingly reduces the source text interference. Unlike in grammatical editing, the stylistic editing resorts to less explicitation and this helps reduce the length of the edited texts.

Structural editing includes stylistic editing but is considered hierarchically the highest and the most radical form of editing strategy. It is necessitated when the source text doesn’t respond adequately to the text type7, target audience and the purpose of editing. It involves mostly subordination and/or coordination of ideas and the corresponding changes in syntactic patterning coupled with summary/rewording/expansion of the source text as the situation demands. Effective editor presence reduces source language interference and increases its domestication.

The Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure’s (1916/1983) invention of the linguistic term ‘sign’ corresponds to the concept of ‘word’, generally considered as the smallest unit of editing. Sign, by nature arbitrary and in a relationship of contrast with other signs in the same language to derive its distinctive meaning, unifies signifier (image) and signified (concept).

Halliday’s (1985/94) systemic analysis of English grammar is based on a hierarchical rank scale starting with ‘morpheme’. He focuses on ‘clause’ as a representation of meaning, and in a ‘simple sentence’, it may be noted the clause always approximates to a sentence.

Newmark (1988) focuses on ‘sentence’ as the natural unit of meaning and states (165) that in spite of transpositions8 and rearrangements, sentence generally retains the status of being the smallest unit in linguistic processing.

In the context of translation, Vinay and Darbelnet reject the ‘word’ as the unit and focus on the ‘semantic field’ rather than on the formal properties of the individual signifier. For them, the unit is “the smallest segment of the utterance whose signs are linked in such a way that they should not be translated individually” (1995:21). They prefer to call this unit as ‘lexicological unit’9 or the ‘unit of thought’.

Eugene Nida (1964:268) points out that in practice the language processing unit will typically tend to be not individual words but small chunks of language building up into the sentence called “meaningful mouthfuls of language”.

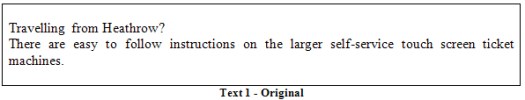

It can be seen that a unit of editing corresponds more to a semantic field than to grammatical units like word, phrase, clause, sentence or even paragraph. As a semantic unit, it is comparable to a ‘unit of thought’. These units of thought in turn are made up of lexicological units which may or may not correspond to the concept of grammatical categories. The example given below is a poster at the underground ticket office at Heathrow airport, London (Hatim and Jeremy 20).

Grammatically, this poster comprises two sentences – an interrogative sentence and an assertive sentence with the existential verb form. By virtue of positioning, the interrogative sentence functions like a title, and the two sentences can be thought of as constituting two paragraphs. Any professional editor working on this short text will process it as one entity in spite of its apparent bifurcation into two sentences or paragraphs since semantically it comprises one thought unit. An interesting editing aspect to be noted in this context is the existence of smaller thought units within larger thought units. Thus an editor is likely to break down the text further into the title and the instruction. The instruction subsequently may be sub-divided into

There are / easy to follow instructions / on the larger self-service touch screen ticket machines.

It can be also noted that even the smaller thought units correspond to semantic units than to grammatical categories. Thus the title is a sentence (shortened with the grammatical subject deleted) and the rest are phrases. Sometimes, a heading can be a unit of thought, at other times a unit of thought may run into paragraphs.

The edited text is guided by the principles of ‘domestication’ and ‘explicitation.’ The existential verb phrase (there are) gives way to a polite phrase (please see) to make the text polite and therefore domesticated to gain the naturalness of the native tongue. Similarly, the over-crowded adjectival phrases and classifiers (larger, self-service, touch screen, ticket) are reduced to minimum (larger) and ‘easy to follow instructions’ hyphenated (easy-to-follow) to render the sense clearer than in the source text.

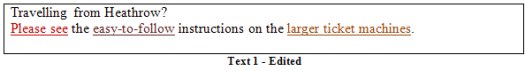

In yet another example (Hatim and Jeremy 19), taken from a leaflet distributed in Madrid airport in 2001 in the background of foot-and-mouth disease outbreak, the text (which is a literal translation of Spanish ST), read as follows:

Analysis of source text/target text pair will indicate that the editing focussed on two thought units – ‘outbreak of the disease’ (unedited) and ‘disinfection of footwear’ (structurally edited) – which do not correspond to any one grammatical unit since one thought unit corresponds to a ‘phrase’ and the other to a ‘clause’.

Also note that the edited text is once again guided by the principles of domestication (all passengers arriving from UK and France are kindly requested) and explicitation (special carpets provided in the airport).

To conclude, Reiss and Vermeer’s concept of ‘functionality’ (1984) is worth referring to as a test for successful transfiguration of a source text into target text. This would amount to expecting the TT to perform the purpose associated with its ST before its transformation. An edited or translated software for example should still deliver the desired action for which it was originally conceived. The functionality of edited/translated literary and advertisement texts will correspond to insulating their stylistic features from violation in the target version. Thus Hemingway’s choice of short, simple sentences in the place of long, complex and compound sentences and Proust’s penchant for embedded sentences are parts of the functionality of their texts since their linguistic style is reflective of their unique world view and therefore basic to the interpretation of their texts. Thus whatever may be the units of editing chosen, the editor has to pay attention to the type of text and its cultural, stylistic and ideological features to render politically correct edited versions.

The notion of the unit of editing can be explored further10 with the help of recent technological developments. The ‘lexicological units’, for example, can be further examined using examples from electronic corpora11 or with the help of a search for the units on any internet search engine (eg; www.google.com). Another possible method is using TAPs (Think–Aloud Protocols) where the editor, novice or professional, is encouraged to ‘think aloud’ while recodifying the ST into TT and is painstakingly recorded to research the editor’s thought processes (Lorscher 1991). The results may be fuzzy because of the problems associated with analysing what is essentially a cognitive process. This suggests that editing unit is a shifting concept in the process of editing and can easily span linguistic boundaries.

In a humanising language teaching environment, ‘editing’ has come out as an effective language teaching tool. This is because editing is primarily a task-based activity the successful completion of which, individually or in a group, gives learners the reward of satisfaction and helps reduce their tension and anxiety of learning considerably. It is assumed this article will give language teachers an insight into the complex mental processes involved in editing which begins with the selection of an appropriate editing unit as the first step of recodifying the source text into an edited text. Teaching is a two-way process where teachers facilitate their learners to un-learn and learn as much as they themselves do. The symbiotic nature of this interaction demands education for the educated as well the educators. As the adage claims, “Every time you teach your students, you are either taught or un-taught!”

1 The sentence quoted appears in Vinay and Darbelnet’s classic work Comparative Stylistics of French and English. Though basically a study in Contrastive Analysis, the work influenced the field of translation studies and contributed to the definition of translation units.

2 Inter-textuality involves the dependence of one text upon another. Whereas vertical inter-textuality is more an allusion, horizontal inter-textuality makes direct reference to another text.

3 Texts themselves are not isolated but function within their own socio-cultural, political and ideological environment.

4 Editing, like translation, is basically a form of interpretation where an editor must aim at rendering (Eco 4-5) “not necessarily the intention of the author but the intention of the text” – the intention of the text being the outcome of an interpretative effort on the part of the editor, as is the case with any reader, critic, or translator.

5 Negotiation is a process (Eco 6) in which “in order to get something, each party renounces something else, and at the end everybody feels satisfied since one cannot have everything.” If editing is viewed as negotiation, the editor is the negotiator between the source text (ST) and the target text (TT) – between their linguistic, cultural and social meanings.

6 Domestication is making a text’s meaning transparent and making its language fit with the expectations of the TT audience (Venuti 21). This strategy involves downplaying the foreign characteristics of the language and culture of the source text by adopting a transparent, fluent style. In contrast, foreignization or foreignizing strategy attempts to “bring out the foreign in the TT itself, sometimes through calquing of ST syntax and lexis or through lexical borrowings that preserve SL items in the TT” (Hatim, Basil, and Jeremy Munday 230).

7 Different text types like narrative, persuasive, and expository require different yardsticks of editing (Reiss 2000).

8 ‘Transposition’ involves change in grammatical features without affecting meaning. For eg; ‘immediately’ for ‘as soon as I start.’ Here meaning remains more or less the same but grammatically ‘a phrase’ is substituted by ‘a ‘clause’ (subordinate).

9 The lexicological unit contains lexical elements grouped together to form a single element of thought.

10 The methodology used in this investigation has been to reconstruct the unit of editing by analysing various source text-target text pairs or based on the surmise from one’s experience of what units are generally used to produce a ‘possible’ edit. Still another method used was to look at draft edits where the revisions may give clues about the mental process involved.

11 Corpora constitute an electronically readable database of naturally produced texts written for genuine communication. Such a corpus can be analysed linguistically by a computer for research purpose.

Eco, Umberto. Mouse or Rat? Translation as Negotiation. London: Phoenix, 2003.

Hatim, Basil, and Jeremy Munday. Translation: An Advanced Resource Book. New York: Routledge, 2004.

Lorscher, W. Translation Performance, Translation Process, and Translation Strategies: A Psycholinguistic Investigation. Tubingen: Gunter Narr, 1991.

Newmark, P. A. Text book of Translation. New York and London: Prentice Hall, 1988.

Nida, E.A. Towards A Science of Translating. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1964.

Reiss, K., and H.J. Vermeer. Grundlegung Einer Allgemeinen Translationstheorie. Tubingen: Niemeyer, 1984.

Reiss, K. Translation Criticism: Potential and Limitations. Trans. EF Rhodes. Manchester: St Jerome and American Bible Society, 2000.

Saussure, F, de. Course in General Linguistics. Trans. and ed. R. Harris. London: Duckworth, 1916/1983.

Shuttleworth, M., and M.Cowie. Dictionary of Translation Studies. Manchester: St. Jerome, 1997.

Vinay, J.P., and J. Darbelnet. Comparative Stylistics of French and English: A Methodology for Translation. Trans. and ed. J.C. Sagar and M.J. Hamel. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 1995.

Venuti, L. The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation. London and New York: Routledge, 1995.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the British Life, Language and Culture course at Pilgrims website.

|