Here and Now: A Language and Culture Course for Teachers in the Post-Brexit U.K.

Mark Andrews, U.K. and Uwe Pohl, Hungary

Mark Andrews is a teacher trainer currently working as training director at SOL (Sharing One Language) in Devon, England. He is interested in the interface of language and culture, working with the local and working with the ‘here and now’ in the world and the ELT classroom. He is a big supporter of teacher associations in Central and Eastern Europe. E-mail: maarkandrews@gmail.com

Uwe Pohl is German-born teacher educator based at Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest. He enjoys working with beginning teachers as a major part of his job. His current professional interests are mentoring, trainer training and intercultural communication. E-mail: uwe.pohl@gmail.com

Menu

Introduction

A positive start to the course in the midst of uncertainty

Now what?!

The Brexit vote in North Devon

How did this happen? - the role of the media and the use of language

Preparing teachers for sensitive fieldwork

Building bridges: learning from and appreciating the diversity of our group

A few general learning points for us

References

1 September 2016 marked the 25th anniversary of the founding of SOL (Sharing One Language) in Devon, UK. In those twenty-five years this charity has welcomed over 46,000 students and 6000 English teachers, mainly from countries in Eastern Central Europe, to South West England. As a result they have come to appreciate not only a variety of SOL language and teacher development courses but also a beautiful part of Britain few of the teachers had known anything about.

But this year’s Authentic British Language and Culture course, a regular feature of SOL teacher training, took place in an entirely new and strange situation – in post-Brexit Britain. The course had brought together 20 English teachers from Romania, Poland, Ukraine, Serbia, the Czech Republic, Kosovo, Croatia, Slovenia and Hungary. All the teachers were keen to explore British culture in and around the town of Barnstaple but wondering whether they were still welcome.

In this article, we would like to share our impressions and insights from working with these English teachers in the U.K. in the immediate aftermath of the Brexit vote on 23 June 2016. We will first describe some of the local/regional features of this vote and how we reacted to it as course leaders. In this way, we hope, to provide a personal account of the experience. We will also highlight a few general considerations for teaching or training in ‘unexpected circumstances’ as well as the particular benefit of co-training in this context.

Like most people, the two course leaders were surprised by the outcome of the referendum just about a week before the course as most opinion polls had seemed to predict a narrow victory for the “Remain” camp. Being EU nationals as well as SOL trainers, we were now wondering what this would mean not just for Britain and the EU in general but also for SOL and its summer courses in the years to come. We were also uncomfortably aware of the fact that the first tangible outcome of the Brexit vote was a wave of (reported) incidents directed at nationals from other EU countries throughout the UK.

Communication via social networks reflected the range of public opinion – from those who felt this referendum should have never happened, to those who believed that many Britons voted without being well-informed or, by contrast, that they knew what they were doing, did the right thing and that leave voters shouldn’t be judged rashly. Here are just a few voices from online posts representing these different perspectives:

“Today is a momentous day in the history of Britain: The British people have voted to leave the EU! Our war heroes and ancestors will be smiling down on our people today for freeing themselves from the shackles of the EU superstate.”

“As always with referenda, many people answered the wrong question. They were not asked – do you think it’s fair that your family and place has been left behind and that nobody at the top seems to care. But that is the question they [actually] answered. And their answer was yes - and they are right. Even though it was the wrong question. The irony and the tragedy of this is that those places that feel left behind and voted leave often have had more money and support from Europe than those that voted to stay.”

“There was a mountain of info available if you could be arsed to locate it. Many voters are beyond facts or experts, though, and voted with their guts.”

“I don't think that everybody is "racist" who voted [LEAVE]. We shouldn't judge them and call everybody ‘racist’ at once, but be open to their fears, desires, as well. Some of them were immigrants (2nd generation). Interesting, isn't it? Yet they voted against the present leaders of the EU. Because they couldn't make themselves heard otherwise.”

In the wake of this referendum outcome, we felt as course leaders that we had to rethink our initial course outline and address the following questions:

- How can we find a positive start to the course while, at the same time acknowledging the participants’ uncertainty and perhaps even worry in the face of this new situation?

- How do we meet the teachers’ need to get more inside information on how the result of the referendum came about without the issue hijacking the course agenda?

- How do we encourage the participants to do extensive fieldwork on British culture – a core element of the course – in their host families, Barnstaple and the surrounding area with sensitivity and without putting them at undue risk?

- How can we turn the situation and issues at hand into an intercultural learning opportunity and make best use of the national diversity of our teachers’ group?

Getting off to a good, motivating start is an essential element of any course. In this case, though, we felt we needed to deal with the situation before the official course began while our group of teachers was making its way from London Heathrow to Barnstaple by coach. Earlier personal communication from participants on arrival had already revealed that many teachers were keen to find out more about the Brexit vote and were concerned about its potential impact on their stay in the U.K.

For this reason, we wanted to send a clear and powerful ‘welcome’ message to these teachers, whose Eastern Central European countries had repeatedly been singled out as the origins of unwanted EU nationals by some British politicians and media. Mark had already brought some T-shirts with a modified SOL logo and was looking for the right opportunity to display it. At the same time we needed to avoid an antagonising pose in public, one that could pit the teachers against anyone who saw things differently in what was to be their home for the next ten days.

In the end we decided to greet the group with a symbolic gesture: as they returned to the coach after a short break in Salisbury, each participant was personally welcomed by the trainers, Péter Medgyes, our guest presenter, and SOL’s director, Grenville Yeo.

All four were sporting the T-shirts and gave each teacher a cowrie shell which had been washed to the shores of England by the gulf stream, enriching the coastal landscape rather than spoiling indigenous English beaches.

For participants to get a local perspective on the ‘big British picture’ is one of the key principles of our culture and language course. For this reason, we added an input section on the background to the referendum to the course programme. Here we would like to highlight the main aspects of that session.

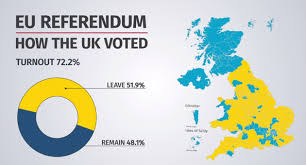

As can be seen on the map above, the West Country – Dorset, Somerset, Devon and Cornwall - overwhelmingly voted ‘Leave’. For those readers who have been to Devon it might also be interesting to know that Ilfracombe, Woolacombe, Lynton and Lynmouth, Appledore, Bideford and Clovelly voted to leave whereas Exeter, the biggest place we visit, voted to remain.

This is the more surprising because North and West Devon as well as Cornwall - being among the poorest and economically disadvantaged areas of Western Europe - have benefitted greatly from EU regional support. Ilfracombe, Appledore, Bideford and Clovelly have received hundreds of thousands of pounds of investment from the European Fisheries Fund. Appledore alone got £600,000 to refurbish its fishing docks and and to build a modern fish processing centre while Ilfracombe got £60,000 for a new fuelling berth. North Devon as a whole was granted “transition status” within the European Union three years ago. Writing in the North Devon Journal at the time, Sir Graham Watson, the then Member of the European Union for the region, said such status meant. that "extra European money for Devon will bring new jobs, will bring economic growth and will provide the funding needed to expand our skills base in the West Country.”Nonetheless, here like elsewhere in Britain, a small but significant majority of people – countrywide 37% of the eligible electorate, voted for the UK to leave the EU.

Relentless right-wing political campaigning over several years which blamed migrants, immigrants from EU countries and the EU as an institution for the UK’s social and economic problems was certainly a key factor in persuading people to vote Leave.

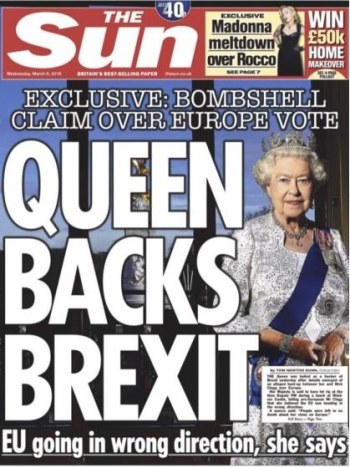

As the headlines above illustrate, some mainstream media and the use of language have played a particular part in this campaign, especially in the crucial months leading up to the referendum.

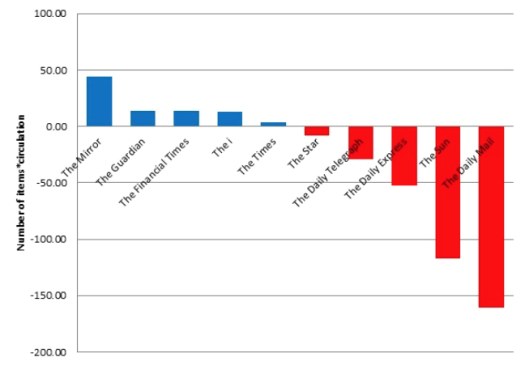

For example, in the print media in the period between 6 May and on the eve of the referendum on 22 June, 80% of the coverage was for “Leave” and 20% for “Remain”. The figure on the right shows the volume of IN (blue) and OUT (red) items weighted by circulation between 6 May and 22 June.

At the same time, tabloids like The Sun, The Daily Mail or The Daily Express deluged the British public with stories that, though not true, contributed to an overall impression that the UK was being overrun by migrants and that ‘sane’ public figures like the Queen favoured leaving the EU.

For example, on 22 May the Sunday Express reported 12 Million Turkish citizens as saying they would come to the UK. This, the paper claimed, raises “the prospect of a migrant influx which would place an unprecedented strain on the UK’s struggling public services including the NHS.” The same day the paper reported that a “deal was already being done to give Turks visa free access” Nowhere did it mention that Turkey will never become a member of the European Union without the agreement of all 28 member countries, which means that any member state (like the UK) can always veto Turkey’s joining the European Union.

Through our use of language we construct the world. One of the most powerful slogans of the LEAVE campaign was “We want our country back!. It is powerful because it sounds like common sense but crudely over-simplifies the process and complexity of working together in an inter-national organization aiming to achieve common goals and standards, however imperfectly.

Taking a longer, historical perspective, there has also always been a kind of ‘island mentality’ which, especially in England, considers Europe an entirely separate place. Britons fly “to Europe”, go “to Europe” for their holidays, Europeans drive on the wrong side of the road, measure distances in kilometers rather than miles and weigh themselves in kilos rather than stones and pounds. And there is the English Channel, which separates the English part of the U.K. from what is often referred to ‘mainland Europe’. “Fog in the Channel, Continent Cut Off" was a regular weather forecast in Britain in the 1930s as well as a newspaper headline. All of these things are expressions of Britain seen as distinct from the rest of Europe. Sometimes this notion is combined with the yearning for an imaginary past, a lost empire and the idea of England as a kind of romantic rural retreat. The problem is that the world has moved on and there is no going back to ‘the way things were’. In his blog, the linguist George Lakoff put it like this:

“Brexit used the metaphor of ‘entering’ and ‘leaving’ the EU. There is a universal metaphor that [nation] states are locations in space: you can enter a state, be deep in some state, and come out that state. If you enter a café and then leave the café, you will be in the same location as before you entered. But that need not be true of states of being. But that was the metaphor used with Brexit; Britons believed that after leaving the EU, things would be as before when the entered the EU. They were wrong. Things changed radically while they were in the EU.”

The Brexit vote has changed the political landscape – nationally and internationally – and the long-term consequences of this result are difficult to predict. What Britons are now definitely left with for a long time to come is a deeply fractured country. As Tony Wright, a fellow-teacher trainer from Devon, wrote in a Facebook comment: “The issue of the EU is more than a simple door-slamming” because none of the deep-seated social and economic problems facing Britain are likely to go away any time soon.

For the past five years a central strand of this course has been an ethnographic approach to cultural study (Corbett 2010). As soon as they arrive in Britain, our participants are encouraged to get out ‘into the field’ - the local context of North Devon - to ‘dig deeper’ and get under the surface of British culture by observing, noting and talking to locals about what they experience on a daily basis. The interviewing part of such fieldwork is tricky at the best of times as it requires some basic knowledge of interviewing techniques as well as a ‘feel’ for what to ask about, who to approach, when and how to initiate an interview with strangers. In the present situation of heightened sensitivities these questions became paramount for an educative and safe intercultural experience.

We therefore led a preparation session on how to conduct effective interviews and, working from an actual interview transcript, got the teachers to arrive at a number of strategies for planning and conducting good interviews, such as

- Use of lead-in questions to warm up the interviewee and put them at ease

- Calling an interviewee by his or her first name

- Listening and observing attentively for any signs of unease or unwillingness to enter a particular topic

- Importance of back-channelling: responding with encouraging responses/noises

- Introducing personal/more difficult questions with a softening statement

- Paying attention to the types of questions asked, e.g. preferably open/ wh-questions

- Thinking about the sequence of questions: from less to more personal ones

- Asking questions in a way that always allows the interview to decline or opt out

- Ample expressions of appreciation for a person’s readiness to be interviewed, to offer personal information and opinions or to be recorded

We were happy to note that, in the course of the next ten days, the teachers interviewed not just their the host families they stayed with but also policemen, lifeguards, surfers, passengers on local buses, shop owners and local residents.

In their diaries many noted what they found interesting in their conversations with the locals about the Brexit issue:

“Very interesting: whoever I met said he’d voted for REMAIN!? So who voted for LEAVE?! …Those who voted for remain are really disappointed and the others seem unsure what they voted for.”

“The genie is out of the bottle: it’s so sad to see that something has definitely changed in this country. When I hear people speaking about it – the Polish shopkeeper, the Danish lifeguard – it seems as if we were in a different time, namely the 1930s…. It’s a kind of ‘déjà vu’ feeling and I can just hope that history won’t repeat itself…”.

“I was shocked to find out that there were some threats to a Polish lady who owns a shop [here]. They bully her children at school. Nevertheless, everybody assured us that we are welcome here and apologised for the result.”

As the English teachers who attend SOL training courses are predominantly from countries in Central and Eastern Europe, the composition of any group tends to be culturally diverse. Over the past few years we have come to appreciate the great potential of the diversity on the course more and more. For us, the people on this course are the course and a fair part of the actual content gets generated by learning from each other. But we also realised after previous courses that doesn’t happen by itself and now pay special attention to extra space and tasks for people to engage with each other.

Here is, for example, an activity we learned from a Hungarian EFL teacher and which we always do on the first day of the course. Each group member randomly picks another’s name and becomes that person’s secret ‘guardian angel’. This means being kind to that person in some small way on a daily basis, such as striking up a conversation, buying them an apple or ice-cream, sitting next to them on the bus. We found such encounters go some way towards overcoming the natural tendency to stay together with ‘your own kind’. They create an opening for empathy and an interest in ‘cultural/national others’.

In a separate session on the make-up of our identities – personal, regional, national – the teachers also introduced some things they had brought from home: realia, symbols, photos or local foods. The idea is to explore these dimensions and to provide a forum for each participant to share what they see as iconic features of their countries and cultures. We have done this activity repeatedly and although participants appreciate the sharing aspect as well as some interesting information, it is not unproblematic.

Showcasing of this kind runs the risk of becoming stereotypical, one-dimensional, static and, occasionally, even offensive. As one teacher observed this time, “[In some group members I noticed a] tendency to glorify one’s country at the expense of another. This is not the point of our course or this session…”

Cultural identity, according to Cultural Studies specialist Stuart Hall, “is a matter of becoming as well as being”. As he also points out, “cultural identities come from somewhere, have histories [but] like everything which is historical, they undergo constant transformation... they are subject to the continuous ‘play' of history, culture and power.” (Hall 1990:225).

So perhaps a productive alternative to ‘showcasing’ would be to look for living connections between cultures. For example, it is interesting to note what appeared on the breakfast table of the authors co-writing this article. Poliska or Polenta or Mamaliga together with figs from a shoot of a tree in Istria Croatia that was replanted in Novi Sad in Serbia, olives from Spain and lyutenitsa from Bulgaria. All of these foods are common to the countries we work in, sometimes with different names, and it might be fascinating to retrace their paths in the play of Central European history.

The 2016 post-Brexit training experience reminded us that educational practice always happens in the ‘here and now’ of the world outside the class or training room. We can, of course, choose to ignore unexpected developments. They may be on everybody’s mind but dealing with them may not be seen as part of a lesson/session plan or, indeed, of our job. But this can lead to the ‘elephant in the room’ phenomenon and is, for us, a missed opportunity. We have found that responding consciously and proactively to ‘real world’ events creates another form of authenticity - (English) language use becomes authentic because it helps to communicate real concerns, beliefs and emotions of the language user. It is also in keeping with Christopher Brumfit’s famous reminder 20 years ago that ELT should be concerned with “the theoretical investigation of real-world problems, in which language is a central issue.” (Brumfit 1995:27).

However, making use of the social context in which language and education are situated is challenging as well as rewarding. It means working with sensitive issues and process, i.e. staying tuned to the participants’ subtle, nuanced responses and changing tack as and when appropriate. From a co-training perspective (Pohl et al 2016), this requires negotiating changes to the programme, keeping constant (eye) contact during shared sessions, reviewing each training day and, generally, being prepared to trust the other trainer’s judgements.

The fact that we are not two British people running the course actually adds to these aspects of co-training. Our similarities as well as our differences – personal, professional, cultural – sensitize us to the importance of looking at people and cultural phenomena in a multidimensional way and makes us appreciate what Kramsch (1993) calls ‘third places’, i.e. the inter-cultural.

A final word about our course in the context of SOL. International reconciliation in Eastern Central Europe is not an explicit part of the organisation’s mission as a British charity. But we believe that all SOL courses are especially suited to positively influencing teachers (and thus their students!) from a region which is still grappling with the legacy of long-standing, territorial and religious conflicts. We agree with historian Theodore Zeldin, who argues persuasively for a different kind of ‘conversation’ between and among people when he writes:

“To know who one’s ancestors were, and what they were proud of, can no longer suffice for people who think of themselves as different from their parents, as being unique with opinions of their own, and who feel uncomfortable with traditions embedded in violence.” (Zeldin 1994:76)

This is why, on our course, building personal relationships and exploring each others’ cultures is given so much space and attention. At a time when the European Union is in such a critical state, we look forward to more opportunities through SOL, regional teacher associations and like-minded international partners to combine language education with the wider goal of furthering peace and understanding on our continent.

Brumfit, C.J. (1995) Teacher professionalism and research. In: G. Cook and B. Seidelhofer (eds.) Principle and Practice in Applied Linguistics. Oxford: OUP.

Corbett, J. (2010) Intercultural Language Activities. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

Kramsch, C. (1993) Context and Culture in Language Teaching. Oxford: OUP.

Hall, S. (1990) Cultural identity and diaspora. In: Rutherford, J. (ed.) Identity, Community, Culture, Difference. London: Lawrence & Wishart, p. 225.

Lakoff, G. (2003) Metaphors We Live By. London: The University of Chicago Press.

Pohl, U., Szesztay, M and T. Wright (2016) In Praise of Team Training. ELT Professional. Issue 103, March, p. 57-61.

The People’s Referendum Report 2016. Remain United: A Progressive Alliance for European Unity

Zeldin, T. (1994) An Intimate History of Humanity. Harpercollins Publishers.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|