An English Teacher’s Inquiry into Own Instructional Practices

Stefan Rathert, Turkey

Stefan Rathert has been working for more than 17 years as an English teacher at Kahramanmaraş Sütçü İmam University, Turkey. He has written articles for and about Humanising Language Teaching (together with Zühal Okan in ELT Journal, 2015, 69/4). His research interests include professional development and teaching methodology. E-mail: strathert@gmail.com

Menu

Introduction

Identifying a problem in my instructional practice

The role of teacher language and teacher talk in language learning

Questioning

Wait-time

Aim of the study

Methodology

Participants and context

Data collection tools and procedures

Results and discussions

Questionnaire

Semi-structured interview

Wait-Time

Transcriptions

Teacher journal

Conclusions and implications

References

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

In this paper I revisit an instance of data-led reflective practice (Walsh & Mann, 2015), in which I examined my own instructional practice. The inquiry, which I carried out two years ago, examined teacher talk, questioning and wait time. Apart from presenting the development of the data collection tools, the procedures followed and the results gained, I attempt to give an account of the challenges I faced and benefits I reaped.

Teaching young adult EFL learners at a Turkish state university has its distinct challenges, especially when the university is located in a rather remote area of the country and therefore lacks prestige: Students selecting such a university not only have gained low scores in the student selection examination and often possess a certain learner profile which is strikingly different from that of students’ entering more prestigious universities, but also often come with negative attitudes towards learning English not seldom resulting from a frustrating English learning experience at secondary and high school.

For these reasons, it is of utmost importance to create a climate in which students are eager to participate actively in the learning process. Obviously, there are numerous factors which play a role in generating such a positive climate. For teachers, their own instructional practices in the classroom are critical because they can modify them. Thus, rather than blaming students for their negative feelings towards English, lack of motivation, or poor performance in exams or daily classroom work, teachers should constantly question their own classroom practice as reflective practitioners (Schön, 1991; Bartlett, 1990).

In my own teaching practice, I have often noticed that, even if there is apparently a good relationship between me and my learners, over a period of time ‘bad habits’ break through, i.e. part of the learners lose their interest in my classes and seem to ‘miss the train’ being unable to follow the course of the lesson. Needless to say, this is a frustrating experience for both the teacher and the learners. Speaking with some certainty about my own perception, such a situation is likely to cause a feeling of being rejected and to trigger negative feelings towards my students because they seemingly do not accept what I offer in my class.

Naturally, I cannot be sure of how my students perceive my classes. I observe ‘hopeless cases’ who completely give up following the lessons actively (and consequently stop studying outside the classroom, e.g. by reading graded readers or using course book CD-ROMs) obviously being unable to make sense of learning English. Additionally I hypothesize that my attempts to create a communicative focus in my classes as well as my expectation of students to be active (rather than only receptive) might be a problem if we concede that there is a mismatch to their previous learning experience.

As a response to this perceived problem I asked two colleagues of mine to observe my classes independently to get outsider opinions. While one of the observers told me that the input I gave was too challenging being too much over the students’ level, the other observer denied the existence of such a problem. One observer found that I did not use praise/reward sufficiently. Either observer indicated that there was a lot of interaction in my class, but the thread of the lessons got lost now and then. One of the observers pointed with great certainty to a lack of sufficient wait-time I gave my students after asking a question.

Based particularly on this observation I hypothesized that I do not allocate sufficient time to my students for their answers, especially to those students who perform weakly forcing them to participate actively in the lesson and being impatient with them when answers are not provided immediately. Furthermore, I possibly repeat questions too fast or reformulate questions without giving enough time to answer, a ‘strategy’ which probably confuses the weaker students, so that they ‘miss the train’ in the lesson.

During this study, I gave reading skill classes (two groups, each three hours per week), in which I did not have to deal with teaching grammar explicitly and intensively. This gave me the opportunity to focus on content rather than on form. There were often, especially in pre- and post-reading activities, discussions (provided by the reading skill book used), which served my more or less communicative language teaching. Also in the while-reading stage of a lesson, I tried to give students space to negotiate meaning, believing that, if both teacher and learners are responsible for classroom interaction, language acquisition most likely takes place following the social constructivist theory of learning (cf. Walsh, 2003, pp. 124-5). However, I observed that sometimes the extrovert students dominated the classes and the participation in my classes was not satisfactorily spread. Furthermore, lessons sometimes seemed to lack ‘structure’, i.e. parts of a lesson proceeded in an uncontrolled way.

The importance of teacher language and talk for instructed SLA has been widely acknowledged. Research emphasizes that teacher language is likely to elicit learning when it provides opportunities for learners to negotiate meaning and express themselves, or clarifies lesson content (Harfitt, 2008; Walsh, 2003, Walsh, 2002). Its adequateness to its pedagogic goal, referred to as mode by Walsh (2003, 2006), is essential for eliciting learner participation. Walsh distinguishes four modes: managerial mode (aiming at organizing classroom interaction, setting up activities), materials mode (aiming at dealing with material used for language learning), skills and systems mode (aiming at focusing on meaning, form or skills) and classroom context mode (aiming at personalizing by making learners express themselves). Walsh has developed ‘Self-Evaluation of Teacher Talk’ (SETT) procedures. They allow the teacher to analyse part of a lesson by checking if the teacher language is congruent to the specific mode present; the mode is defined by the pedagogic goal that underlies it. Ideally, teachers using SETT procedures are enabled to identify a part of their lesson by matching it to one of the modes, and then to assess their own teacher language used in this specific situation in terms of appropriateness to the mode.

Questioning, a specific form of teacher language, is probably the most frequent kind of teacher talk in the classroom serving a great deal of functions. Questioning does not have to be done in form of interrogatives exclusively, but can also occur in form of e.g. statements or imperatives. It is commonly understood as the first part of the conventional IRF structure (Initiation – Response – Feedback); it is distinguished between display questions, in which the teacher knows the answer, and referential questions, in which the information to be given in the answer is unknown to the teacher and which are consequently characterized by a higher cognitive level (Ur, 1996; Crookes and Chaudron, 2001). Referential questions, in particular, have been regarded as an effective tool to elicit greater student participation (Harfitt, 2008) and they are likely, especially when students’ opinions are asked, to generate a feeling of satisfaction in students since they allow them to express an opinion that is related to their own knowledge or experience (Ragawanti, 2009).

Ur (1996, p. 230) offers a criteria catalogue for effective questioning. She proposes

- clarity (do the learners understand the meaning of the question?);

- learning value (is the question relevant for the learning process?);

- interest (is the question interesting for the learners?);

- availability (is the question suitable regarding the level of the learners group or does it only address advanced students?);

- extension (is the question likely to elicit a variety of answers?); this criterion might not be valid when display questions are asked;

- teacher reaction (can the students be sure that their answers will be accepted with respect?).

as categories to be used in analysis of effective classroom questioning.

Wait-time refers to the length of time teachers give students to answer a question. It is believed that giving students sufficient time to answer will have positive effects on the quality of students’ answers and consequently contribute to language learning (Nunan, 1991; Ur, 1996; Crookes & Chaudron, 2001). Nunan (1991) reports that teachers generally give less than one second wait time and even after training they fail to give more than one or two seconds wait-time; providing three to five seconds wait-time, however, leads to an increase in the length of student answers, increases the number of unsolicited answers, decreases the number of failures to respond and leads to a variety of student responses in terms of extension. Not surprisingly, the teacher’s capability to wait is regarded essential to create a classroom which is conducive for critical and creative thinking (Udall & Daniels, 1991, pp. 74-77). Research, however, suggests no unambiguous picture on how wait-time might affect learning efficiency, and the complexity of classroom interaction suggests that controlling wait-time in spite of the fact that it can be easily manipulated by teachers will not lead to a straightforward improvement of instructional practice (Crookes & Chaudron, 2001, p. 40).

Having identified a potential problem in my own teaching, and examining related literature, I decided to examine my own teaching in order to find answer to the following questions:

- Does the teacher’s questioning create or impede students’ opportunities for learning?

- Is the wait-time appropriate to elicit students’ active participation?

- Do students perceive the teachers’ questioning as useful for their own learning?

This study was carried out in two reading skill classes (3 hours per week) with 25 students (15 female and 10 male) and 21 students (10 female and 11 male), respectively. Both learner groups were in an English preparatory program of a Turkish state university, and the groups were selected conveniently, i.e. the research was done in the classes I taught. The study took four weeks.

In order to answer the research questions, I decided to use four different data collection tools. This decision was not only driven by the need to provide triangulation, but also to investigate my own teacher talk, questioning and wait-time from different perspectives.

A closed-ended questionnaire using a 5-item Likert scale (from strictly agree to strictly disagree) was used in order to understand the students’ perception of the teacher’s questioning (Appendix 1). In formulating the questionnaire items the categories suggested by Ur (1996) were taken into consideration and wait-time was added as a separate category. Formulations were partly taken from Essex College (2011). It was decided to use multi-item scales in designing the questionnaire (Dörney, 2003). For this reason, a set of three questions for each category was written and shown to a group of master students and an academic teacher as well as to some colleagues in the department where the action research was carried out. Suggestions for modification were considered. Then a Turkish native speaker was asked to translate the questionnaire into Turkish and another Turkish native speaker translated it back into English in order to check the translation. After that, the questionnaire items were ordered randomly, and the Turkish version of the questionnaire was then given to a class that I had taught in the first term of the academic year. The students were asked to indicate unintelligible or misleading items, which was not the case. The data of the pilot study were tested for reliability with Cronbach’s Alpha test resulting in an acceptable value of ,748.

For the statistical analysis of the data of the participants, the steps in the pilot study were repeated, and additionally the item scores for the questions belonging to the same category were summed and then divided by 3. Thus, results for the seven categories (and not for each question) were obtained. Moreover, the data for the two learner groups were processed as a single data set since the potential differences between the learner groups were not in the interest of the study, and it was assumed that the results would be more reliable because of the larger data set. The data were processed for mean, mode, and standard deviation.

A sample of the students involved in the action research was interviewed by the teacher in order to get a deeper understanding of the students’ perceptions. The semi-structured interview was applied after the questionnaire results had been gained. For the semi-structured interview the questions were developed covering three areas of clarity of lesson structure, satisfaction with own participation and participation in the learner group (see Appendix 2).

To select the participants for the interview, a purposive sampling was used: I decided to ask a very proficient, a fairly proficient and a less proficient student in each class, respectively, in order to cover a variety of students. While inviting students, I was asked in two cases to accept a classmate as participant in the interview so that two interviews became ‘pair-interviews’. The interviews were analyzed with content analysis (Miles and Huberman, 1994).

In order to analyze the teacher’s questioning style and wait-time allocated a videotape recording was used. Videos were recorded over a period of four weeks. Parts of lessons which were teacher-centered were recorded. The duration of all videotape recordings was approximately 390 minutes. Wait-times were measured by using the video recording, i.e. specialist equipment was not used, which turned out to be problematic. Transcripts were made to reveal patterns of classroom discourse characteristic for my questioning (Harfitt, 2008; Thornbury, 1996). However, for practical reasons and due to time constraints transcripts were made only for those parts which were regarded relevant for the first research question.

Additionally, a journal was kept by the researcher (entries usually written immediately after the lessons) in order to report learner reactions to activities applied in the lessons. A journal as a tool to collect information was chosen since it is not only a record of events, but also provides opportunities for interpreting, analyzing, evaluating and planning teaching as a part of professional reflection (Borg, 2006; Richards & Lockhardt, 1996). Thus, the journal complemented the results gained with the other instrumentation tools and procedures.

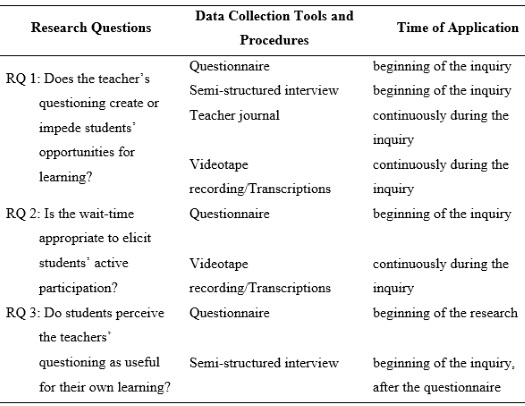

The data collection tools and procedures in relation to the research questions are shown in the Table 1. Additionally, the time of application is given for each instrument.

Table 1

Data collection tools and procedures in relation to research questions

In this chapter, the results of the data analysis are presented separately for each data collection tool and procedure. Then, the analysis results are discussed.

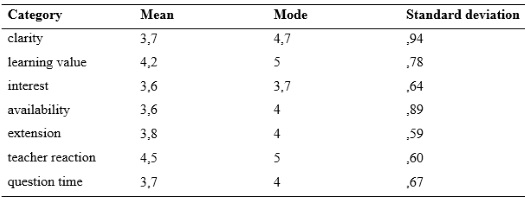

The questionnaire results are given in Table 2. Due to the fact that part of the learners in one of the classes were continuously absent and, thus, had no base to evaluate my teaching, instead of the 46 participants in both groups, only 40 participants took part in the questionnaire. Since multi-item scales were used, the answers for questions belonging to the same category were summed up and divided by 3. Therefore, some values for mode are not given in integers, but in decimal numbers. The reliability was tested with Cronbach’s Alpha resulting in a value of ,867.

Table 2

Learner perceptions of teacher talk, questioning and wait-time

The results for the category clarity indicate that, in general, the participants agree or strictly agree to the statement that the questions I ask are clear and understandable. The mean and standard deviation values suggest, however, that this is not true for all participants. It can be concluded that the clarity in questioning is not given for the less proficient students.

The results for the category learning value indicate that my questioning is regarded relevant for the learning process. Both the value for the mean and the standard deviation suggest that this is valid for most of the learners.

In the category interest it was asked if the questions I ask in the lessons are likely to attract the interest of the participants. In this category, the results obtained are the lowest among all categories. Even though the results suggest that the participants agree that the questions are appealing, a tendency towards uncertainty can be stated.

The category availability refers to the suitability of the questions according to the level of learner proficiency, i.e. if the language I use can be understood by the learners. Similarly to the results for interest, availability is evaluated as given but not among all learners. The results suggest that less proficient learners may have problem in understanding my questions.

Also the results for extension, which refers to the potential of questioning to trigger a variety of answers, show that the participants generally think that my questioning possesses such a feature; however, a slight tendency towards uncertainty can be observed.

A clear result is given to the issue if I react in a respectful way to the answers given by my students. Both mean and mode indicate that the participants agree or strongly agree that their answers are accepted respectfully.

The questions in the category question time aimed to find out if the participants received the wait-time provided by my as sufficient in order to give an answer. Similarly to the results for interest, availability and extension the results indicate general satisfaction among the participants but also suggest uncertainty to some extent.

By and large the questionnaire results suggested rather the absence of serious problems related to my own questioning. However, it cannot be excluded that part of the participants gave ‘good marks’ to my questioning as a reward for the – according to my own observations - generally good relationship that I have to my students.

To come to a deeper understanding of the - in my perception - not always satisfactory classroom interaction I asked four participants in each group if they had problems in following my lesson and to evaluate their own participation as well as the participation in the learner group in general.

In the analysis some common patterns emerged: The participants said that it was possible for them to follow my classes and that the language I used was not too distant from their own level. One of the less proficient students (who, in the meantime, failed to enter the final exam because of low grade point average) said:

I can follow your lesson so so. It depends on how well prepared I come to class. (…) I don’t participate enough. That’s because I don’t understand and I don’t understand because I’m not well prepared. The lack of own participation depends on me (#5).

The individual participation and that of classmates or the learner group in general were seen critical by the students. The students argued that lack of active participation was an issue of individual responsibility rather than connected to teacher behaviour. On enquiry, participants said that non-participating students didn’t like English because they had learned English for too long a time and got fed up with it. One participant assumed that the habit of being passive had remained as an outcome of high school experience. Moreover, low self-efficacy was given as an account. Another point brought forward was that the preparatory program was primarily directed towards exams and not on learning English:

We aren’t focused on learning English but on studying for exams. We move forward too fast in the lessons [to cover the content to be asked in exams]. Our single aim is to pass exam. When we fail, we give up working. This is a general problem in class. Everybody thinks of nothing but exams. (…) Teachers go to the next unit even if students haven’t grasped the content (#4).

According to explanations of some of the participants, a climate of resignation has spread in part of the preparatory students as the following excerpts show:

You can do what you want. It will be impossible for you to reach students who are not interested in English (#1).

Students don’t want to participate because they are not interested in the lesson. Those students who don’t want to participate don’t participate in other lessons, either. This is not related to you, but there is no wish to participate (#2).

You can change your teaching style however you want, if we aren’t willing, nothing will change (#5).

The students who never come [to the lessons] have developed a prejudice against English, so they don’t come (#6).

To sum up, the interviews have revealed that there is in fact a lack of active involvement of part of the students in classroom interaction. This has been identified as a general problem in all classes. According to the students’ explanations, negative attitudes towards English are particularly caused by a strong focus on exams in the preparatory program. Nearly all interviewees emphasized the learners’ own responsibility for this situation.

Due to the fact that no special equipment for measuring the wait-time was available, this part of data collection turned out to be extremely difficult. Because of insufficient sound quality, it was often not clear if an unintelligible student’s utterance was a response to a question or unrelated. This was particularly a problem since students often started to speak without hand raising. In my classes this practice has come into being, probably due to the low number of learners, and is not regarded disturbing. To find a practical solution, I decided to focus on passages in which the measure of wait time was possible. In this regard, the results are limited as they cannot claim to be representative.

The passages were five 3-4 minute periods of teacher-fronted parts in lessons. 103 questions were counted in these parts. I assumed that different types of questions require different large amounts of wait-time. I decided to use Bloom’s taxonomy of thinking levels as a criterion and identified questions as related to knowledge or comprehension level as one group, and related to application, analysis, synthesis and evaluation as the second group (Udall and Daniels, 1991, p. 114). Wait-time was defined as the span between the moment when the teacher stopped to talk and the moment when the student started to talk (for methodological aspects of wait-time research see Heinze & Erhard, 2006). Time was measured with the time display of the media player on the computer, which is another source for inaccurate results. 85 questions were asked at lower thinking levels and only 18 at higher thinking level. The average wait-time for questions at lower thinking level was 1,63 seconds, the average wait-time, the average wait-time for questions at higher thinking level was 2,35. Two results are striking: the low wait-time at both levels, and the low number of questions at higher thinking level.

Apart from the statistical evidence, the analyses of the transcriptions in the next paragraph strongly suggest inappropriateness of wait-time in my questioning.

Even though the insufficient sound quality definitely also affected the transcription of part of the lessons, these constraints seemed less severe for this form of data processing in the study.

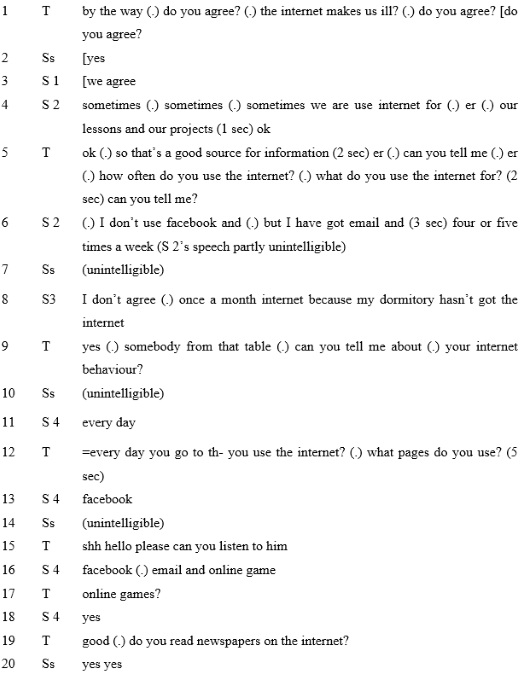

In the following, I will analyze three transcripts which I believe contain representative samples for recurrent problematic patterns in my questioning. I will use the third person singular referring to me since I believe that this form of ‘stepping back’ helps analyze and reflect on the own teaching in a more accurate manner. For transcription conventions see Appendix 3.

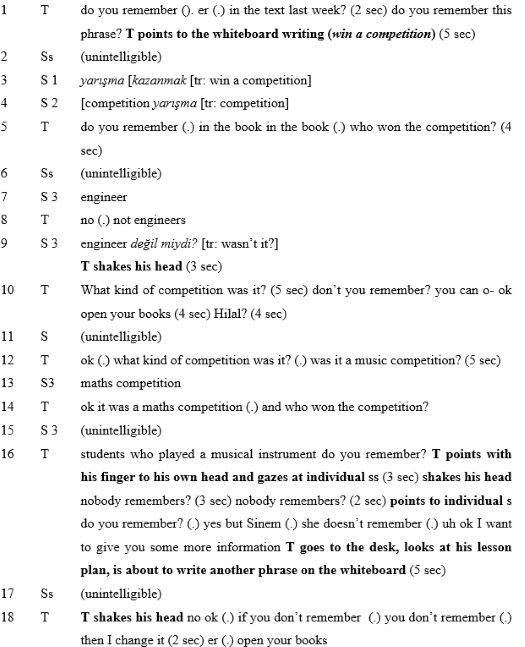

Extract 1

In the first example, the teacher repeats the content of a reading done in the previous week. He writes key phrases from the text on the whiteboard in order to elicit students’ utterances referring to the reading. The students are told to keep the book closed.

The questioning in turn 1 is problematic for some reasons. The teacher asks the students if they remember a phrase occurring in the reading. It is probably not clear for the students what answer is expected. After a rather long pause (5 seconds), a Turkish translation is provided by two students (turn 3 and 4). In turn 5, the teacher asks who won the competition, which is responded with a wrong answer. Having not received a correct answer and leaving the question unanswered, in turn 10 another question is raised. After this question remains unanswered as well, the teacher deviates from the plan and allows the students to open the book. As the recording reveals, part of the students does not look at the book, but start muttering. In turn 12, the teacher resumes the question from turn 10, but without giving time, the question is modified to a yes-no question. Turn 16 is also remarkable since the teacher here changes the classroom mode (Walsh, 2003): the focus is removed from the content of the reading text (material mode in Walsh’s terminology) and the teacher actually complains about the (in the teacher’s perception) students’ poor performance in an offensive way addressing several students directly through eye contact. The questions (do you remember?) remain unanswered and obviously lack any pedagogic goal. Finally, the teacher completely deviates from his lesson plan and works on the reading text in the book.

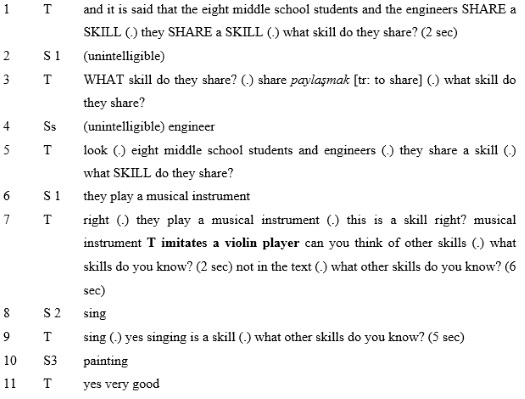

Extract 2

With a similar problematic questioning begins extract 2. The teacher asks questions about a reading text, which the students can look at.

During the first five turns, students’ participation is not satisfactory even though a translation of a vocabulary item is given in turn 3. The question posed is a display question that requires identifying an item in the reading text from the students. The teacher, however, tries to fill the gap immediately after posing the question instead of giving sufficient time for students to find the answer. Thus, opportunities for learning are not provided. In turn 7, a mode switching occurs and the teacher tries to personalize the topic ‘skills’ by giving students opportunities to name some other skills and (later in the discourse not transcribed here) to tell what skills they are good at. After posing the question in turn 7, six seconds wait-time is provided, and students start to contribute. The following interaction (not shown here) is characterized by extended learner turns and short teacher turns.

Extract 3

The importance of asking clear, unambiguous questions in the language classroom is illustrated in excerpt 3. In groups, the students have thought of supporting arguments for the statement ‘The Internet makes us ill’. After collecting the arguments on the whiteboard, the following classroom interaction takes place:

In this part of the lesson, the students are invited to express their own opinions on the statement introduced earlier in the lesson. In the terminology of Walsh (2006), this part of the lesson refers to the mode of classroom context, in which learners are given the opportunity to express themselves in an established context by practicing oral fluency. Classroom interaction is characterized by shorter teacher and longer learner turns, avoidance or minimizing of error correction, content feedback, scaffolding and dominance of referential questions as well as requests for clarification.

Taking this self-evaluation model as criterion for excerpt 3, it can be stated, that the opening questions in turn 1 are not appropriate at all. Apart from the repetition of the question, which emerged as a habitual pattern in many of the classroom interactions analyzed, a yes-no question is not suitable to trigger students’ opinions towards content. This example as well as the question in turn 19 clearly violate the demand for questions to have the quality of eliciting a variety of answers (category extension; Ur, 1996) Unsurprisingly, the first responses are rather unreflective in form of ‘yes’ (turn 2 and 20). In turn 4 it is then student 2, one of the most proficient students in the class, who produces a piece of language that takes a stand on the content. The scaffolding in turn 5 (so that’s a good source for information) can be evaluated positively according to SETT. In the same turn, however, two referential questions are asked in immediate succession, and after an insufficient amount of wait-time can you tell me? is added. Similarly, asking two questions at a time is also done in turn 12 (note the misplaced use of pages). In this turn student 4 is addressed. The delay in responding (5 seconds) might be accounted for with the inappropriate questioning.

A better questioning behaviour is displayed in turn 9, although the students’ response cannot be considered satisfactory. Another, quite often observed questioning habit emerges in turn 17: A contribution of student 4 is echoed with rising intonation for no obvious reason triggering a ‘yes’. All in all, the questions used in this extract seemed to occur rather accidentally, although this lesson stage was planned as classroom context mode at this point of the lesson. We will return to this point in the conclusion. Compared to interactual features established by Walsh (2006), this extract is a poor sample of classroom context mode.

For this action research I started to keep a journal. In the first proposal I planned to use field notes. However, I changed this plan because the concept of teacher journals as a tool for holistic reflection, which I learned about in an MA seminar, convinced me of its advantages.

Even though I knew that the journal entries would be used as data for this inquiry, I wrote surprisingly few things about questioning. The most frequently emerging issue was that of lack of active student participation. As I formulated in an entry, “participation was in waves, sometimes more, sometimes less”. In teacher-centered parts of lessons, which I will concentrate here on, I reported quite often that only the more proficient students participated in the classroom interaction. This was particularly true for content-directed conversations, in which students usually had to respond in a personal way. Language work, especially when I introduced new vocabulary without using the learners’ mother tongue, was perceived well by students. At such lesson stages, students have the opportunity to negotiate meaning, which seems intellectually appealing also to those students whose participation is limited in other parts of the lesson.

At times, I clearly formulated weaknesses of lessons as a result of flawed teacher behaviour, e.g., “the following classroom conversation wasn’t satisfying because only few students participated, and it seemed unstructured. I should explicitly write down questions I will ask in class in the lesson plan”. The inappropriateness of questioning was addressed in this entry: “The intro of the lesson was not OK because it didn’t activate students and my own questioning was a helpless attempt to achieve goals”.

The issue of participation was also mentioned in the journal entries as regards absenteeism. After the midterm exam in the middle of the term, a lot of students decided to stay away from class. This was another factor that made teaching difficult: “It is difficult to engage students when half of the class is absent and there is no ‘fire’”.

I conducted this reflective practice in order to evaluate a part of my own teaching. For this reason, I decided to collect data from three different perspectives: the students’ perception of my teaching through questionnaire and semi-structured interview, my own reflection written down in a teacher journal, and a video recording with. In particular, the analysis of the video material in form of transcripts turned out to be the most powerful tool to find an answer to the research questions. So, the answer to the first research question is that there are aspects of my own questioning that impede students’ opportunities for learning. Addressing the second question I would like to claim that, despite the technical constraints that hindered an accurate analysis, wait-time provided was frequently not suitable to elicit the students’ active participation.

The third research question dealt with the students’ perception of my teaching. Even though I would not like to doubt the honesty with which the students answered the questionnaire, it seems to me that the questionnaire results have to be handled with care for two reasons: Firstly, the students might have given positive responses because there is obviously a good, cooperative relationship between me and my students. Secondly, I perceived that the students were delighted when I told them to carry out a kind of classroom research. The video camera in the classroom, the invitation to interviews might have given them a feeling of being appreciated, which was possibly reflected in the questionnaire results. Interestingly, even though the wait-time measuring turned out to be highly problematic and, indeed, unsatisfactory, I assume that the results I gained about wait-time are more reliable than those related to the students’ perception of my teaching.

The analysis has specifically produced the following results:

- In my questioning, I have the tendency

- not to provide learners with sufficient wait-time,

- to ‘fill the gap’, i.e. to avoid moments of silence,

- to ask questions in immediate succession,

- to reformulate questions in immediate succession so that clarity is diminished,

- to formulate questions that are not in accordance with the pedagogic goal of the lesson stage,

- primarily to ask questions addressing lower levels of thinking.

- My teaching is not as firmly grounded on communicative principles as I have assumed.

- In the preparatory program in my department there is a climate of resignation among part of the students.

- Teaching is too much focused on exams and not on teaching English in the learners’ perception.

Apparently, the last three bullet points represented results emerging as by-products of the inquiry indicating issues beyond my own teaching. As implication, I reasoned that I would have to work on my own questioning, which would include the following strategies:

- applying techniques to enhance wait-time as suggested by Udall and Daniels (1991, pp 74-77) (e.g. counting silently to ten after posing a question),

- formulating questions in lesson plans beforehand to avoid using questions seemingly accidental and to address higher levels of thinking,

- asking colleagues to observe my lessons under the specific aspect of questioning,

- occasionally recording lessons and making transcripts, which I found particularly useful to make things visible.

Making things visible and challenging assumptions about the own teaching might be the subtitle to this kind of reflective practice I carried out. Even though I was only able to identify problematic issues in my teaching (without applying and testing solutions), and even though - surely due to lack of own experience - one of the data collection procedures could not be applied as planned, I should like to point out that the experience of this inquiry has raised my awareness of the importance of researching the own classroom to become a reflective teacher. (Actually, since the time of this study, I have regularly invited colleagues to peer observation and asked them to focus on teacher talk, questioning and wait-time, and I have collected minute papers from my students to get feedback about my teaching.)

Saying this, I hope that my paper is not another sample of what Maley (2016) has labelled pseudo-research produced in MA or Ph.D. programmes (even though it is the outcome of an MA course), but may be regarded as an example of data-led reflective practice giving a model for and/or encouraging other teachers to examine their own instructional practice. Needless to say, my inquiry (to avoid the word ‘research’) raises the question of how applicable research is for language teachers or in how far teacher research should be conceptualized differently from academic research to make it relevant and accessible for teachers (cf. Smith, 2015). This is indeed the subject of an intriguing debate in this journal (http://old.hltmag.co.uk/jun16/mart02.htm). From my own point of view, an inquiry into own instructional practice requires some systematic approach, which includes reviewing (research-informed) literature, aim setting and a systematic way of collecting, analyzing and interpreting data; otherwise it is likely to produce unreliable and invalid information about teaching and learning. In that sense, inquiry into instructional practice conducted as systematic investigation has indeed the quality of research doable by and relevant for teachers (Saraceni, 2016).

Bartlett, L. (1990). Teacher development through reflective teaching. In J.C. Richards & D. Nunan (Eds.) Second Language Teacher Education (pp. 202-214). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Borg, S. (2006). Teacher cognition and language education. Research and practice. London: Continuum.

Crookes, G. & Chaudron, C. (2001).Guidelines for language classroom instruction. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (pp. 29-42). Heinle & Heinle.

Dörneyi, Z. (2003). Questionnaires in second language research. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Essex College (2011), Students’ Feedback Questionnaire. Retrieved March 2, 2012 from: http://www.essexcollege.co.uk/links-data/downloads/EC_Students_Feedback_Feb_2012.pdf

Harfitt, G. J. (2008). Exploiting transcription of identical subject content lessons. ELT Journal, 62(2), 173-181.

Heinze, A. & Erhard, E. (2006). How much time do students have to think about teacher questions? An investigation of the quick succession of teacher questions and student responses in the German mathematics classroom. Zentralblatt für Didaktik der Mathematik 38(5), 388-398. Retrieved March 15, 2012 from: http://subs.emis.de/journals/ZDM/zdm065a4.pdf

Maley, A. (2016).‘More research is needed’ – a mantra too far? Humanising Language Teaching 18(3). Received 30 October, 2016 from: http://old.hltmag.co.uk/jun16/mart01.htm#C9.

Miles, M.B. and Huberman, A.M. (1994) Qualitative data analysis.2nd edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Nunan, D. (1991). Language teaching methodology. A handbook for teachers. Prentice Hall.

Ragawanti, D. T. (2009). Questions and questioning technique: A view of Indonesian students’ preferences. k@ta 11:2, 155-169. Retrieved December 12, 2011 from: http://puslit2.petra.ac.id/ejournal/index.php/ing/article/viewFile/17891/17819

Richards, J.C. & Lockhardt, C. (1996). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Saraceni, M. (2016). Re-defining research. Humanising Language Teaching 18(3). Received 30 October, 2016 from: http://old.hltmag.co.uk/jun16/mart02.htm

Schön, D. (1991). The reflective practitioner. New York: Basic Books.

Smith, R. (2015). [Review of the book Teacher Research in language teaching: A critical analysis by S. Borg]. ELT Journal 69(2), 205-208.

Thornbury, S. (1996). Teachers research teacher talk. ELT Journal 50(4), 279-289.

Udall, A.E. & Daniels, J.E. (1991). Creative active thinkers. 9 strategies for a thoughtful classroom. Chicago: Zephyr Press.

Üstünel, E. & Seedhouse, P. (2005). Why that, in that language, right now? Code-switching and pedagogical focus. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 15(3), 302-325.

Ur, P. (1996). A course in language teaching. Practice and theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Walsh, S. (2002). Construction or obstruction: teacher talk and learner involvement in the EFL classroom. Language Teaching Research 6(1), 3-23.

Walsh, S. (2003). Developing interactional awareness in the second language classroom through teacher self-evaluation. Language Awareness 12(2), 124-142.

Walsh, S. (2006). Talking the talk of the TESOL classroom. ELT Journal 60(2), 133-141.

Walsh, S., & Mann, S. (2015). Doing reflective practice: a data-led way forward. ELT Journal 69(4), 351-362.

Please click HERE to download appendix 1.

Please click HERE to download appendix 2.

Please click HERE to download appendix 3.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|