Translated Writing: A Unique Opportunity for Second Language Learners to Write More Effectively

Reza Zabihi and Zeinab Hashemi Moghaddam, Iran

Reza Zabihi is Assistant Professor of Applied Linguistics at University of Neyshabur, Neyshabur, Iran. His major research interests include individual differences in second language writing. He has published over 50 research articles in local and international journals and has served on the editorial boards of nine international journals; affiliation: University of Neyshabur, Neyshabur, Iran. E-mail: zabihi@neyshabur.ac.ir

Zeinab Hashemi Moghaddam holds an MA degree in TEFL from Khorasan e Razavi Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Neyshabur, Iran. Her main areas of research is language teaching and L2 writing; affiliation: Department of English, Khorasan e Razavi Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Neyshabur, Iran. E-mail: zb.hashemi69@gmail.com

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Method

Participants

Instruments

Procedures

Results

Discussion

References

A growing body of research has been investigating how L2 writers, while writing in the second language (L2), make use of their first language (L1). In view of this, the present study was conducted to examine the effect of translation on the enhancement of Iranian Intermediate EFL learners’ writing ability. The participants (N = 30) were prompted to perform two writing tasks: (a) writing directly in English (learners’ L2) and (b) writing in their L1 (Persian) and then translating it into English. They were also assigned a checklist, a retrospective verbal report, to express their attitudes towards the two modes of writing. Analysis of the results revealed that translation can be of help to some learners to enhance their writing ability. In effect, the results indicated that there was a significant difference between two writing tasks in terms of using expressions, transitions, and grammatical points. The vast majority (80%) of students reported they think in Persian, as “often” or “always” while doing the English task in the direct writing mode. This finding suggests that teachers should incorporate translation strategies into their writing courses and explicitly teach students how to employ effective strategies in different situations. The provision of instruction and practice in using L1, particularly in planning and organizing learners’ writings, may be of benefit to some learners in performing certain writing tasks.

Research in first or second language writing has attracted the attention of educators for decades (Friedlander 1990; Uzawa 1996; van Weijen, van den Bergh, Rijlaarsdam & Sanders, 2009). Early studies show that L2 writers use L1 in L2 writing but the extent to which they do in their writing is imprecise or the amount they use are not the same (Wolfersberger, 2003; van Weijen, et al., 2009). Since writers with low L2 proficiency are likely to rely on their L1 than those who are proficient in L2, several studies have tried to examine the L1 transfer in L2 writing process (Jones & Tetroe, 1987 as cited in Wolfersberger, 2003). For one thing, a number of studies have been conducted to discover how L2 writers make use of their first language (L1) while writing in the second language.

The role of the native language comprehensively influences a second language acquisition which includes the use of forms and meanings, and culture. Lado (1957) stated, “Individuals tend to transfer the forms and meanings, and the distribution of forms and meanings of their native language and culture to the foreign language and culture both productively when attempting to speak the language and to act in the culture, and receptively when attempting to grasp and understand the language and the culture as practiced by natives (p. 2).” According to Kaplan’s (1972) claim, the errors in L2 writing are due to the intervention of L1. He explains further that second language learners write expository writing style in English with different organizational patterns from those of native speakers as they can be seen as the rhetorical organization from the L1 and culture. Regarding cognitive influence, Boroditsky (2001) found that abstract thoughts developed in L1 affected L2 use. He concluded that L1 thinking influenced learners for L2 meaning construction.

In fact, past research has demonstrated significant correlations between L1 and ESL data (Silva, 1992). Taking a translation approach to writing in the second language, the cohesion of the text, including markers of transition and syntactic complexity, could actually be enhanced. Further, given the broader use of terminologies and set of phrases in line with L1 expressions, learners would be able to develop the extent of their expressions (Cohen & Brooks-Carson, 2001). Similarly, Brooks (1996) showed that employing such an approach to writing would significantly improve learners’ writings as well as syntactic complexity, including more frequent use of coordination and subordination. Cohen and Brooks-Carson (2001) also argue that the translated approach to writing might cause the lower quality of grammar, in particular syntax. Thus, it seems necessary that the investigators consider participants’ ability to use, a vast number of cohesive devices, complex syntactic structures, breadth of terminologies, and grammatical structures in L1.

Several studies show that the transfer from learners’ L1 to their L2 writing affects the quality of their L2 writing. For example, Wang and Wen (2002) examined how Chinese university students’ L1 affected their writing and whether their dependence on Chinese was related with their English proficiency. The results showed that students with higher English proficiency relied less on Chinese when they wrote in English than those with lower English proficiency. The students were more likely to rely on L1 when they were generating and organizing ideas, but more likely to rely on L2 when occupied in writing a text. Similarly, Wang (2003) examined the frequency of adult Chinese ESL learners’ language switching of L1 to L2 writing and the effects on the quality of their L2 writing. The study found that adult ESL learners’ L2 proficiency did not decrease the frequency of language switching from L1 to L2 writing.

Other studies have demonstrated similarities between the L1and L2 composing processes. Jones and Tetroe (1987), for example, looked at Spanish-speaking ESL writers generating texts in Spanish and ESL; they found that the quality of planning transfers from Ll to L2 and thus certain aspects of a writer's L1 writing process transfer to that person's L2 writing process. In an analysis of advanced ESL learners with differing Ll backgrounds composing in their respective Ll and ESL, Hall (1990) showed that the students' revisions were strikingly similar across languages, suggesting use of a single system in revising across Ll and L2. Further, Arndt's (1987) study with Chinese-speaking graduate-level ESL students also revealed that the processes and strategies of each individual writer remain consistent across Ll and L2 composing (compare Lay, 1982).

These studies seem not only to provide evidence for transfer of already existing Ll writing strategy to L2 writing (compare Berman, 1994), but also to suggest the possibility of" composing universals" that go beyond the likeness of Ll and L2 writing (Krapels, 1990, p. 53). Corresponding to the abovementioned studies, Cohen and Brooks-Carson (2001) examined the usefulness of another approach to writing in a second language. They invited thirty-nine intermediate students of French to work on two different writing tasks: (a) writing directly in French (L2) and (b) writing in first language (English), and then translating it into French. The participants were also asked to fill out a number of scales concerning the strategies they used while writing directly in French as well as those they used while writing first in English and then translating it into French as well as their attitudes regarding two modes of writing. Findings indicated that, while 26 students outperformed in their direct writing across all the writing scales, 13 of them did better in the translated one. It is worth mentioning that no grammatical significant differences were established across the two writing modes as there was a significant difference in scales of expression, transition and clauses. In addition, according to the results of the retrospective verbal report, it was revealed that learners were often thinking in English while writing directly into French. These results indicated that the two writing tasks were actually not of a different nature.

Wolfersberger (2003), who only studied low proficiency L2 writers, also found that they frequently used their L1 during prewriting and made use of translating from their L1 to their L2 in order to compensate for their limited ability to write in their L2. In line with this, Beare and Bourdages (2007) found that highly proficient bilingual writers hardly used their L1 at all during L2 writing (p. 159). Moreover, Woodall (2002) complicated the discussion even further, by including the difference between cognate and non-cognate languages as an additional independent variable in his study. He found that overall, intermediate-proficiency writers switched more often from their L1 to their L2 than high proficiency writers, but this effect was influenced by whether they were writing in non-cognate (Japanese/English) or cognate languages (Spanish/English). Therefore, Woodall argued that there seem to be important differences in L1 use between writers. Indeed, ‘‘some students appeared to control their L-S [language switching], using their L1 as a tool. For others, L-S seemed out of control, and the L1 seemed more like a Crutch to obtain cognitive stability’’ (Woodall, 2002, p. 20).

The general finding appears to be that the use of the L1 during L2 writing can be beneficial, but not in all situations and not for all writers (Cohen & Brooks-Carson, 2001). This appears to depend on writers’ L2 proficiency (Akyel, 1994; Beare & Bourdages, 2007; Wang, 2003; Wang & Wen, 2002; Wolfersberger, 2003; Woodall, 2002), the type of task (Wang & Wen, 2002), topic-knowledge (Friedlander, 1990; Krapels, 1990; Lay, 1982; Qi, 1998), or on whether the L1 and the L2 are cognate or non-cognate languages (Woodall, 2002). Furthermore, the reasons for L1 use and which cognitive activities are carried out in L1 also remain somewhat unclear. The L1 can be used to solve linguistic or lower-order problems (Beare, 2000; Jones &Tetroe, 1987; Qi, 1998; Wang, 2003; Woodall, 2002), but is also used for higher-order activities such as planning or to prevent cognitive overload (Beare, 2000; Centeno-Cortes & Jimenez, 2004; Cohen & Brooks-Carson, 2001; Jones & Tetroe, 1987; Knutson, 2006; Krapels, 1990; Qi, 1998; Uzawa & Cumming, 1989; Wang, 2003; Whalen & Menard, 1995;Woodall, 2002). Wolfersberger (2003), who only studied low proficiency L2 writers, also found that they frequently used their L1 during prewriting and made use of translating from their L1 to their L2 in order to compensate for their limited ability to write in their L2. In line with this, Beare and Bourdages (2007) found that highly proficient bilingual writers hardly used their L1 at all during L2 writing (p. 159).

Unfortunately, studies directly relating L1 use during L2 writing to text quality are few and far between, but there are indications that both translation from the L1 to the L2 and L1 use during L2 writing can be beneficial for some writers (Cohen & Brooks-Carson, 2001; Kobayashi & Rinnert, 1992; Uzawa, 1996; Uzawa & Cumming, 1989). Moreover, unlike Cohen and Brooks-Carson’s (2001) study which explored the effect of translation on the writing of English and Spanish Intermediate learners of French while participants were under time pressure, the present study was designed to focus on Iranian intermediate EFL learners where there was no time pressure for the learners’ performance. Considering the importance of knowing about learners’ attitudes on second language learning (Al-Tamimi&Shuib, 2009; Chalak & Kassaian, 2010; Ismail, Hussin, & Darus, 2012) and granted the fact that to understand second language writing and its differences with its first language counterpart, it is recommended that researchers analyze not only learners’ writings but also their attitudes (Silva, 1992). The following research questions are going to be addressed in the present study:

- What effect does translation have on the Iranian Elementary EFL learners’ writing ability?

- What is the nature of the learners’ attitudes towards direct English writing vs. translated English writing?

The present study uses a non-experimental intact group comparative research design (Fraenkel & Wallen, 2006) to investigate the effect of translation (from L1) on L2 learners’ writing ability.

Based on an Oxford Placement Test (OPT), a total of 30 Intermediate Iranian learners of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) studying at the Mehr Hatef Institute were selected for this study. The overall rationale for the selection of intermediate-level learners was that these participants, due to their relative lack of L2 proficiency, were more likely to resort to their L1 (Persian) and then translate into the L2 (English). They ranged in age from 15 to 24.

Oxford Placement Test (OPT), contain 60 multiple choice items will select as an instrument. This test consist of grammar (20 items), vocabulary (20 items), reading comprehension (20 items) with a writing section. The time for answering the questions is 45 minutes. The overall rationale for the selection of intermediate-level learners is that these participants, due to their relative lack of L2 proficiency, were more likely to resort to their L1 (Persian) and then translate into the L2 (English). Therefore, after correcting the papers, 30 learners will select as the intermediate-level group based on the categorizations put forth in the OPT manual. I use a pilot study for this kind of test, therefore this test indicating high reliability.

Writing Tasks: we had two topics for the writing tasks, taken from the course book (American File) covering during the course of study: (a) An Email to Friends to Thank Them. (writing first in Persian and then translate into English). (b) Nightmare Trip (writing directly in English).

Checklist: Students’ Attitudes toward direct and translated writing task. In addition, students were given a separate checklist to investigate their attitudes towards the two kinds of writing tasks. The checklist is a modified version of the one used in a previous study by Cohen and Brooks-Carson (2001). Learners will ask to indicate based on a five-point rating scale the degree to which they agreed with statements about the effectiveness of translation as a strategy and to supply additional feedback on the experiences they had during the completion of the essay tasks. Cronbach’s alpha, the index of internal consistency, was computed for each of the multi-item factors, direct writing mode and translated writing mode.

Data Collection: The data for the present study will collect in four class sessions. In the first session, students will ask to write the first writing task, Nightmare Trip, directly in English. In the second session, participants will ask to write the second writing task, An Email to Friends to Thank Them, in their native language, Persian. In the third session, participants will ask to translate the Persian text into English. In the last session, students were given a checklist assessing their attitudes concerning the two writing tasks.

Data Analysis: Two experienced raters who have been teaching English for more than ten years will score the two writing tasks. The inter-rater reliability between the raters was obtained at .80, indicating high reliability. A multi-trait rating scale, taken from the previous study (Cohen & Brooks-Carson, 2001), were used to assess four multi-trait aspects of writing that focused more on the form and function of the writing than on the content of the ideas: expression (freedom from translation effect, variety in vocabulary, and sense of the language), transitions (organizational structure, clarity of point, and smoothness of connectors), clauses (use of subordination and use of relative pronouns), and grammar (prepositions/ articles, noun/adjective agreement, and verbs).

The data obtained from the checklist will codify and enter into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, version 16). Descriptive statistics will use to determine the mean and standard deviations of the statements in the checklist. A Paired samples t-test was run to determine the significant difference between students’ performance in the translated and direct English writings.

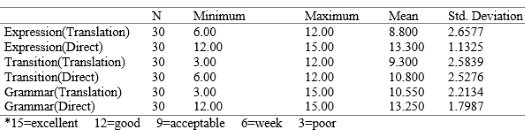

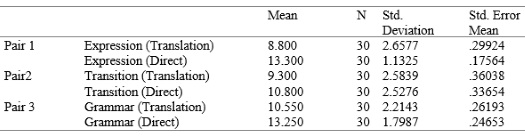

With reference to the first research question that asked whether translation has any effect on learners’ second language writing ability, the researcher at first scored learners’ writings in terms of expressions, transitions, and grammatical structures. As shown in Table 1, students performed better in the direct writing task than in the translated one. Students’ performances on the direct writing task were rather good in terms of expression (mean=13.300), transition (mean=10.800), and grammar (mean=13.250), while their performances on the translated task were rather weak in terms of expression (mean=8.800), transition (mean=9.30), and grammar (mean=10.55).

In other words, these findings pointed to the superiority of performances in the direct writing task than in the translated one. Specifically, learners performed better on the direct writing task than on the translated one in terms of expression, transition, and grammar. These results are to some extent similar to those of Cohen and Brooks-Carson (2001) in which two-thirds of the students performed better on the direct writing task across all scales, while one-third of the students outperformed the translated task.

Table 1

Students’ Performances in Translated Writing Task vs. Direct Writing Task

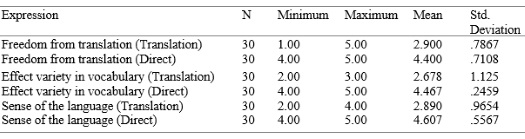

In terms of the expressions used in both writing tasks, only slight negative transfer in the direct writing task (mean=4.40) and a moderate negative transfer in the translated task (mean=2.9) were discovered. The variety of vocabularies in the direct writing task was good (mean=4.46), whereas the variety of vocabularies used in the translated writing task was week (mean=2.678). Regarding the sense of language, there was good control over native-like expressions in the direct writing task (mean=4.60), while the control over native-like expressions in the translated task was week with a mean of 2.890 (Table 2). Therefore, it may be concluded that translating from an L1 into the target language would not be a proper writing strategy as it established the deterioration of writing abilities in terms of using expressions.

Table 2

Performances in Translated Writing Task vs. Direct Writing Task in terms of Expressions

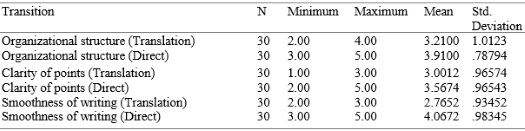

Relating to the transitions used, the results recommended a partial difference between the translated writing as opposed to the direct writing task. The organizational structure, clarity of points, and smoothness of the writing were partially good in the direct writing task with the means of 3.91, 3.56 and 4.06. On the other hand, organizational structure, clarity of points were acceptable in the translated writing task with the means of 3.21, 3.0012 and smoothness of the writing was week in the translated writing task with the means of 2.76 (see table 3). Therefore, it would not be a proper writing strategy to translate from a first language into the target language as the research reported in this study pointed to the deterioration of writing abilities in terms of using transitions.

Table 3

Students’ Performances in Translated Writing Task vs. Direct Writing Task in terms of Transitions

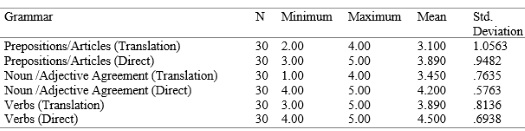

Regarding the grammatical points, the use of prepositions/articles (mean=3.89), noun/adjective agreements (mean=4.20) and verbs (mean=4.50) in the direct writing task was good. However, the use of prepositions/articles (mean=3.10), noun/adjective agreements (mean=3.45) and verbs (mean=3.89) in the translated writing task was acceptable (see table 4). Thus, given the results reported in table 4 which pointed to the deterioration of writing abilities in terms of using grammatical structures, translation from an L1 into the target language does not seem to be a proper writing strategy.

Table 4

Students’ Performances in Translated Writing Task vs. Direct Writing Task in terms of Grammar

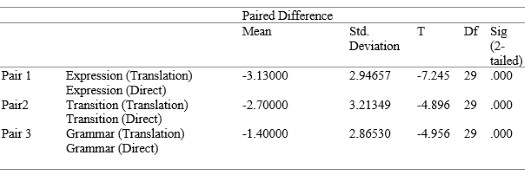

In order to establish whether there is a significant difference between the two writing tasks, a paired sample t-test was performed. The results recommended significant differences between the two writing tasks in terms of using expressions (p=.000 0.05), transitions (p=.000 0.05), and grammatical points (p=.000 0.05), though the difference between means were not high (see tables 5 and 6). As can be seen in these tables, learners had greater success in their performance on the direct writing task than on the translated one regarding the use of expressions, transitions, and grammatical structures. This finding also indicates that translating from an L1 into the target language is not a proper strategy.

Table 5

Paired Samples Statistics for Performances in Translated Writing Task vs. Direct Writing Task

Table 6

A Paired Samples T-test for Performances in Translated Writing task vs. Direct Writing Task

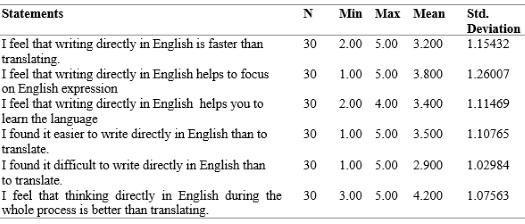

This study also attempted to assess students’ attitudes towards the two writing tasks (the second research question) and, in doing so, descriptive statistics was run. A key finding resulting from the retrospective verbal report data gathered by means of checklists was similar to that of Cohen and Brooks-Carson (2001), considering the fact that the direct writing mode was not quite “direct”. The results are summarized in tables 7, 8, and 9. Based on the findings, students considered direct English writing to be faster than translated writing (mean=3.2); they largely found direct English writing as a help to focus on English expressions (mean=3.8) and to learn English better (mean=3.4) (see Table 7). They felt that thinking in English during the whole process was better than translating (mean=3.5) and moderately found it easier to write directly into English than to translate (mean=2.9).

The findings indicated that learners perceived direct English writing to be faster than its translated counterpart. In sum, the majority of learners expressed their tendencies to write directly in English, while only a few of them preferred to translate from L1 into L2.

Table 7

Students’ Attitudes toward Direct Writing Task

*1= not at all 2= a little 3= moderately 4= quite a bit 5= completely

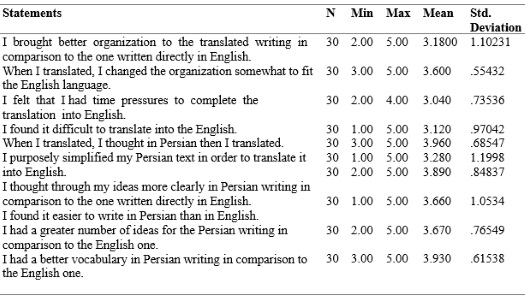

In the translated writing task, participants mentioned that they moderately brought better organization to the translated writing (mean=3.18) in comparison to the one written directly in English. They pointed out that they changed the organization of the first writing to fit the English language (mean=3.6), had time pressure to complete the translation task (mean=3.04), found translating to English difficult (mean=3.12), and thought in Persian before translating into English (mean=3.96) (see table 8). They also stated that they purposely simplified their Persian text before translating it into English (mean=3.28).

Although the subjects were instructed to write one essay directly in English without translation, just like the study of Kobayashi and Rinnert (1992), the vast majority of them reported thinking in Persian “often” or “always” while doing the English essay in the direct writing mode. This finding also supported the results of the study carried out by Weijen et al. (2009) whose subjects used their first language while doing the task in their second language. In other words, the subjects in the present study reported having thought in Persian most of the time that they were supposedly engaged in the direct English writing task. This finding, supported by Cohen and Brooks-Carson (2001), proposes that, while in the translation approach learners were involved in written translation on the paper, in direct writing they were involved in mental translation. Such a finding also coincides with those of Cohen and Brooks-Carson (2001) where participants in the direct writing condition reported using their L1 very often while writing in their L2, even though they were not supposed to. This is also in line with Sasaki’s (2002) study in which novice learners, subsequent to the instruction, still tended to translate from their L1 into the L2 while writing in L2.

Table 8

Students’ Attitudes toward Translated Writing Task

*1= not at all; 2= a little; 3= moderately; 4= quite a bit; 5= completely

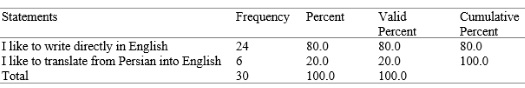

Moreover, the findings revealed that students largely thought more clearly about their ideas in Persian (mean=3.8), found writing in L1 easier (mean=3.66), had a greater number of ideas (mean=3.67) and a better vocabulary in Persian writing task (mean=3.93) in comparison to the English one (see table 8). In sum, 80% of the subjects expressed that they tended to write directly in English, while 20% preferred translating from L1 into L2 (see table 9).

Table 9

Students’ Attitudes towards Translated Writing task vs. Direct Writing task

This study was aimed at examining the effect of translation on enhancing Iranian Intermediate EFL learners’ writing ability. To explore the results of two different composing processes, one writing directly in English and the other writing first in Persian and then translating into English ,as well as the administration of a checklist to the subjects to assess their attitudes toward the two modes of writing.

The analysis of the data gave us a number of findings regarding the effectiveness of direct and translated writing in the Iranian EFL context. The findings pointed to differences between two writing tasks in terms of the use of expressions, transitions, and grammatical points. Despite that fact that translation may be time-consuming and undoubtedly harmful to language learning in the long term, they still thought of translation as an effective means to practice English essay writing and help English learning as well as enlarge vocabulary and master the grammatical structures if there would be the help of dictionaries and other possible references and helps.

It is interesting to note that the students reported thinking through Persian much of the time that they were supposedly engaged in the direct English writing task. This report suggests that, while for the translated writing task they were engaged in written translation on paper, they were nonetheless engaged in mental translation during the direct writing task. The point is that the two tasks, then, were not necessarily distinct in nature, but rather overlapping.

Indications from the psycholinguistic literature are that the connection between concepts and the L1 is much stronger than between concepts and the L2, which would explain why at early stages of L2 acquisition there is a tendency among learners to attach L2 words to L1 equivalents through whatever form of translation (Kroll & de Groot, 1997). Translation serves to reduce the load on working memory since instead of going directly from the concepts to their L2 representation, the L2 writers are first expressing the concepts in the L1 and then translating to the L2.

As noted at the outset of this paper, studies by both Brooks (1996) with English-speaking writers of French and Kobayashi and Rinnert (1992) with Japanese writers of EFL had found distinct advantages for the translated writing mode. In the Brooks study, the students had been asked to prepare the two essays out of class, first in draft form and then in revised form, using software for French word-processing. So they had spent a considerable amount of time preparing the essays in both the direct and translated writing modes. In the Kobayashi and Rinnert study, the students were given an hour of class time to write each of two essays on two successive days, one in Japanese L1 and then one in the FL, English. Then, on a third day they were given another hour to translate one of the essays into English.

This procedure gave them ample time to assure that their translated essays were of the highest quality they could produce. The current study was intended to simulate typical writing situations that students face when they participate in classroom assessment. Perhaps it is a better measure of the impact of a given writing mode since it is possible that in the other two studies, the extra time factor could have neutralized differences or perhaps even given the advantage to one of the modes, such as to translate writing, which is not the most effective choice for some or many learners when under time pressure.

The present study highlighted a number of important results regarding the advantages and disadvantages of writing directly in L2 and translated writing from L1 to L2. Those results helped in extracting the following instructional recommendations. Teachers should expose students directly to the norms of writing in L2 and provide them with enough and continuous opportunities to practice writing in different genres in L2. At early stages, teachers should explicitly highlight the differences between the norms of writing in L1 and L2 as writing in Persian is to some extent different from writing in English. Students should always be encouraged to reflect on their writing experience in L2 and they should always be encouraged to use their first language writing experience when writing in L2. Finally, students should be helped to become aware of the strategies they use when writing in L1 and they should be taught how to transfer and use those strategies when writing in L2.

However, the present study was conducted within certain limitations. For one, it may be argued that the small size of the sample in this study may not be a true representative of the larger population of Iranian EFL learners; another study might involve a larger sample of the participants from different educational settings. The reliability of the results was affected by different issues. One of these is that most of the studies relied on a small number of participants. Small samples have sampling errors and therefore, lower the reliability of the results (Alreck & Settle, 1995). Second, the participants’ attitudes were obtained merely by the administration of a questionnaire. Apparently this does not allow a sound generalization regarding their attitudes about direct versus translated writing tasks. Other studies may be carried out to investigate whether the results of this study are true with qualitative research methods including interviews and think-aloud protocols.

Be that as it may, based on the findings discussed above, the following pedagogical implications can be put forward so as to help language teachers in dealing effectively with second language writing in the classroom. Most notably, the fact that learners have used their L1 while writing in L2 suggests that teachers should incorporate translation strategies into their writing courses and explicitly teach students why and how to employ effective strategies in different situations; as was pointed out by Cohen and Brooks-Carson (2001). Learners may think about the topic in the L1, engage in mental translation, or write a text in their L1 and then translate it into the L2. Earlier research (Jones & Tetroe, 1987; Friedlander, 1990; Kobayashi & Rinnert, 1992) had suggested that the L1 or dominant language may be best used to plan and organize the writing while the TL is best for writing on the sentential level.

Results from this study would support the notion that thinking through the L1 or dominant language may be a benefit for some students in certain writing tasks, and therefore the study seems to lend some support to the value of generating training or coaching materials dealing with translation strategies. For example, the materials could provide suggestions for how the systematic use of translation might serve effectively as a means for organizing ideas and for expressing them in a concise, lexically acceptable, and grammatically appropriate manner. Given the significant relationship between ratings for variety in vocabulary and for both ease in direct writing and ease in translating, it would seem that particularly at an intermediate level, training could focus on how students go about selecting appropriate vocabulary for a given writing context and the role that mental and written translation might play in the selection process.

Needless to say, training materials would need to include a series of caveats, indicating that translation strategies may have a differential effect, depending on the nature of the task (e.g., an in-class essay with/without time pressure, an in-class essay exam, or an essay as homework), the topic, the learning style preferences of the writer, and so forth. Furthermore, teachers can use the results of the checklist concerning students’ attitudes toward the translated writing task versus the direct writing task as a guide to determine the strategies that have the potential to improve learners’ writing ability. They can provide instruction and practice in using L1, especially in planning and organizing their writings, which may be a benefit for some learners in performing on certain writing tasks. Third, cultivating, maintaining and enhancing the perceptions of EFL learners toward different writing tasks should be an important goal to be pursued by all educators in the field of second language writing.

Akyel, A. (1994). First language use in EFL writing: Planning in Turkish vs. planning in English. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4, 169–197.

Alreck, P. L. & Settle, R. (1995). The Survey Research Handbook. Boston, Massachusetts: Irwin McGraw-Hill.

Arndt, V. (1987). Six writers in search of texts: a protocol-based study of L1 and L2 writing. ELT Journal, 41 (4), 257-267. Oxford.

Al -Tamimi, A., & Shuib, M. (2009). Motivation and Attitudes towards Learning English: A Study of Petroleum Engineering Undergraduates at Hadhramout University of Sciences and Technology. GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies, 9(2), 29-55.

Beare, S., & Bourdages, J. S. (2007). Skilled Writers’ Generating Strategies in L1 and L2: An Exploratory Study. In G. Rijlaarsdam (Series Ed.) & M. Torrance, L. VanWaes, & D. Galbraith (Vol. Eds.), Studies in Writing Vol. 20, Writing and Cognition: Research and Applications (pp. 151-161). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Brooks, A. W. (1996). An Examination of Native Language Processing in Foreign Language Writing. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Vanderbilt University, Nashville.

Centeno-Cortes, B., & Jimenez Jimenez, A. (2004). Problem-solving Tasks in a Foreign Language: The Importance of the L1 in Private Verbal Thinking. International Journal of Applied Linguistics.14, 7-35.

Chalak, A., & Kassaian, Z. (2010). Motivation and Attitudes of Iranian Undergraduate EFL Students towards Learning English. GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies, 10 (2), 37-56.

Cohen, A. D., & Brooks-Carson, A. (2001). Research on Direct Versus Translated Writing: Students’ Strategies and Their Results. The Modern Language Journal, 85(2) 169¬ 188.

Fraenkel, J.R., & Wallen, N.E. (2006). How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education (7th ed ). Forth Worth: Holt Rinehart and Winston Inc.

Hall, C. (1990). Managing the complexity of revising across languages. TESOL Quarterly, 24, 4340.

Ismail, N., Hussin, S., & Darus, S. (2012). ESL Students’ Attitude, Learning Problems, and Needs for Online Writing. GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies, 12(4), 1089¬-1107.

Jones, S., & Tetroe, J. (1987). Composing in a second language. In A. Matsuhashi (Ed.), Writing in real time: Modelling production processes (pp. 34–57). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Kaplan, R (1972). Cultural thought patterns in inter-cultural education. In H.B. Allen & RN. Campbell (Eds.), Teaching English as a second language: A book of readings (2nd ed., pp.294-310). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Knutson, E. M. (2006). Thinking in English, Writing in French. The French Review, 80(1), 88-109.

Kobayashi, H., & Rinnert, C. (1992). Effects of first language on second language writing: Translation versus direct composition. Language Learning, 42, 183–215.

Krapels, A. R. (1990). An overview of second language writing process research. In B. Kroll (Ed.), Second language writing: Research insights for the classroom (pp. 37–56). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lado, R. (1957). Linguistics across cultures. Ann Arbor: Michigan University Press.

Lay, N. D. S. (1982). Composing processes of adult ESL learners: A case study. TESOL Quarterly, 16, 406.

Qi, D. S. (1998). An inquiry into language-switching in second language composing processes. Canadian Modern Language Review, 54, 413–435.

Uzawa, K. (1996). Second language learners’ processes of L1 writing, L2 writing and translation from L1 into L2. Journal of Second Language Writing, 5, 271–294.

Uzawa, K., & Cumming, A. (1989). Writing strategies in Japanese as a foreign language: Lowering or keeping up the standards. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 46, 178-194.

Van Weijen, Daphne et al. (2009). L1 use during L2 writing: an empirical study of a complex phenomenon. Journal of Second Language Writing, 18(4), 235-250.

Wang, L. (2003). Switching to first language among writers with differing second-language proficiency. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12, 347–375.

Wang, W., & Wen, Q. (2002). L1 use in the L2 composing process: An exploratory study of 16 Chinese EFL writers. Journal of Second Language Writing, 11, 225–246.

Whalen, K., & Menard, N. (1995). L1 and L2 writers’ strategic and linguistic knowledge: A model of multiple-level discourse processing. Language Learning, 45, 381–418.

Wolfersberger, M. (2003). L1 to L2 writing process and strategy transfer: A look at lower proficiency writers. TESL-EJ: Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language, 7 (2), 1–15.

Woodall, B. R. (2002). Language-Switching: Using the First Language while Writing in a Second Language. Journal of Second Language Writing, 11, 7-28.

Please check the English Language course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary course at Pilgrims website.

|