Editorial

First published in English Teaching Professional, March 2010, Issue 67

Looping the Loop

Simon Mumford, Turkey

Simon Mumford teaches EAP at Izmir University of Economics, Turkey. He has written on using stories, visuals, drilling, reading aloud, and is especially interested in the creative teaching of grammar. E-mail: simon.mumford@ieu.edu.tr

Menu

What is loop input?

Questions about questions

Preposition placement

Modals

Comparatives and superlatives

Conditional maze

Rule and mistake sentences

Grammar explanations

Articles and missing, wrong and extra words

References

Loop input is a teacher-training technique, described by Tessa Woodward, which creates a parallel between input and training processes. So, for example, a trainer gives the trainees information on dictation – in the form of a dictation. This idea could be extended to contextualising grammatical structures for students. By creating a link between the structure focused on and the activity and/or example sentences used to practise it, teachers can increase their repertoire of activities and provide benefits to learners. Here are some ideas on how this works in practice.

Students play the game ‘Twenty questions’ but, instead of objects, they think of a simple four-word question, e.g. Do you like ice cream? The questioning then involves metalanguage, such as pronouns and auxiliary verbs. You may need to demonstrate first as this is quite a complicated concept. Here is an example game:

S1 OK.

S2 Is it a Yes/No question?

S1 Yes.

S3 Is there an auxiliary verb?

S1 Yes.

S2 Is there the verb to be?

S1 No.

S3 Is it do?

S1 Yes.

S4 Is there a pronoun?

S1 Yes.

S3 Is it you?

S1 Yes.

S4 Is it about sport?

S1 No.

S2 Is it about entertainment?

S1 No.

S4 Is it about food?

S1 Yes.

S3 Is it about savoury food?

S1 No.

S2 Sweet food?

S1 Yes.

S2 Is it Do you like chocolate?

S1 No.

S2 Do you like ice cream?

S1 That’s right.

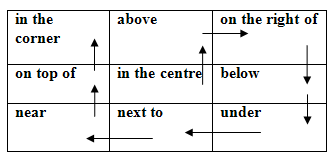

The students are given a blank 3 x 3 grid. The instructions below are read out to them or supplied in written form. The students then have to write the appropriate word or phrase in each square and draw the appropriate arrow to the next square. When their answers have been checked, they work in groups to try to reconstruct the original instructions using the grid.

Instructions

Write ‘in the centre’ in the centre square. Write ‘above’ above it. On the right of ‘above’ write ‘on the right of’. Write ‘below’ below it. Write ‘under’ under ‘below’. Next to ‘under’ write ‘next to’. Near ‘next to’ write ‘near’, and on top of ‘near’ write ‘on top of’. In the last square, write ‘in the corner’.

Solution:

Modal verbs are often used to talk about rules, but modals themselves are subject to rules, so we can use them as content and metalanguage. Here is a ‘true or false’ quiz about modal verbs.

True or false?

- May can be used instead of can in requests and permission.

- We mustn’t use don’t have to instead of mustn’t.

- We must use to after ought.

- We must use to after must.

- Only should can be used for advice.

- Ought to can often replace should for advice.

- We can replace can with could in requests.

- We should use must for advice.

- In certain situations we may write shan’t for shall not.

- We must use to after let, but we are not allowed to use to after allow.

Solution: 1T, 2T, 3T, 4F, 5F (ought to can also be used), 6T, 7T, 8F, 9T, 10F

The students put the following sentences, which all contain comparative and superlative structures, in the correct order, according to the instructions given in the sentences:

- Simon says the sentence which has the most ‘s’ sounds inside should certainly be situated in the most central position.

- The longest sentence, with the most vocabulary items and, therefore, the greatest number of letters and the longest distance between the first and the last words and the most information, goes first.

- The shortest goes last.

- Of the two remaining sentences, the one that has greater complexity should be placed between the longest sentence and the centre.

- The easier one should go next to the shortest sentence.

Solution: b, d, a, e, c

To complete this maze, the students need to understand both the instructions and the example conditional sentences given. Start at Square 1.

Square 1

If there will be a mistake in this sentence, you would have gone to Square 4, but if there is no mistakes, go to 3.

|

Square 2

If I were you, I’d go to Square 8.

If I was you, I’d go to Square 7.

Go to the square given in the most grammatically correct sentence.

|

Square 3

If unless means the same as if, go to 6. If it doesn’t, go to 12.

|

Square 4

If you got the last answer correct, go to 6. If you did not, go back to 1.

|

Square 5

If this square is number 5, go to 10. But just supposing it had been number 6, then you would have had to go to 3.

|

Square 6

If you didn’t study English, you wouldn’t be able to understand this sentence.

If this sentence is correct, go to 11, if it is incorrect, go to 10.

|

Square 7

If your father had been a billionaire, you wouldn’t have to work.

If this is a good sentence, go to 2. If not, go to 10.

|

Square 8

If the if clause always has to come first, go to Square 10.

Go to Square 5 if it can come after the main clause.

|

Square 9

If eight minus one makes ten, go to square 10. If it doesn’t, go to the square which is the correct answer to this sum.

|

Square 10

If you have visited all the other squares before coming to this one, then you have correctly completed the maze. If not, start again!

|

Square 11

If this square is in the third column and the bottom row, go to 3. If not go to 12.

|

Square 12

If you are doing this between three and five o’clock in the morning, go to 2. If not, go to 9.

|

Solution:

Square 1: there is a mistake; Square 4: landing here shows you are correct, go to 6; Square 6: correct; Square 11: it is; Square 3: it doesn’t; Square 12: you’re not; Square 9: it makes 7; Square 7: a correct mixed conditional (past condition with result now); Square 2: were is traditionally correct; Square 8: the sentences show that the second is correct; Square 5: ignore the unreal conditional: Square 10: Finished!

To help the students notice mistakes, contextualise each one in a sentence that gives the rule, and ask them to correct the errors. (Answers given in brackets.)

- He always using present continuous without the verb to be. (He is always…)

- You know how to use an auxiliary verb in present simple questions? (Do you ...?)

- If you will show me how to use ‘if’ with the present simple, I will not make a mistake. (If you show …)

- I forgetted that some past tense verbs are irregular. (forgot)

- For making sentences expressing purpose, use an infinitive. (To make …)

- Use ‘a’ the first time you introduce a word, but use ‘the’ for a same word later. (… for the same word ...)

- Teachers should not to let students use unnecessary words. (… not let students …)

- When use an adverb clause, don’t forget to use a participle. (When using …)

- don’t forget to start every sentence with a capital letter and end with a full stop (Don’t … stop.)

- You don’t need to use a conjunction before a clause that which starts with a wh- word. (… clause that or which ... but not both)

The following sentences, all taken from Cambridge Grammar of English, contain an example of the grammar point they describe. More advanced students can be asked to highlight the part of the sentence that illustrates the point, as shown here.

- A defining relative clause identifies the noun which it post-modifies and distinguishes it from other nouns. (p 327)

- Often adverbs are fully integrated in the clause. However, adverbs may be less integrated in the clause structure and may modify the whole structure or utterance. (p 458)

- Present day English has four main processes of word formation: prefixation, suffixation, conversion and compounding. (p 474)

- A subordinate clause can be part of a sentence when it is dependent on the main clause. (p 554)

- Regular or habitual events are usually referred to in the present simple. (p 599) (active or passive)

One type of grammar exercise omits necessary words and adds unnecessary words. The students’ task is to correct these. The articles a and the are useful in the metalanguage used to refer to the missing or extra words: eg A verb is needed here. The preposition is wrong/unnecessary. The indefinite article denotes something missing and the definite article refers to a word which is wrong/unnecessary. The reason for this is that, for a missing verb, we are not referring to a definite word at this stage, only pointing out that one type of word (a verb) is missing. On the other hand, where there is an extra, unnecessary word, because we can all see the particular word we are referring to on the paper, we use a definite article. The following demonstrates an exercise on articles:

Correct the following sentence: I went for holiday to the France, and I had wonderful time swimming in a sea.

‘There should be an a before holiday and wonderful.’

‘The the before France is unnecessary.’

‘The a before sea is wrong. It should be the.’

(The bold words show articles used as metalanguage, words in italics refer to words in the sentence.)

Solution. I went for a holiday to France and I had a wonderful time swimming in the sea.

Example sentences about imaginary people or unfamiliar places may have little relevance to the students. One alternative is to make the important information, the language itself, the content of the sentences. Associations and parallels between content and activity can lead to new ways of thinking about language and, as Tessa Woodward puts it, exploit the possibility that ‘certain people learn more deeply as a result of … reverberation between process and content’.

Carter, R. and McCarthy, M. Cambridge Grammar of English CUP, 2006

Woodward, T ‘Loop input’ ELT Journal 57/3, 2003

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English Language Improvement for Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|