The Effects of Unseen Observation on Teachers’ Behaviors Associated with their Classroom Talk

Saeed Ayiewbey and Ali Rayati Damavandi, Iran

Saeed Ayiewbey received his M.A. from Mazandaran University, Iran. He has lectured in Iranian Universities including IAU and PNU universities. His research interests include teacher education, language testing and discourse analysis. E-mail: saeedayiewbey@gmail.com

Rajabali Rayati Damavandi is an assistant professor in the department of English Language and Literature, Mazandaran University, Iran. He has a Ph.D. in Applied Linguistics and he has been teaching BA and MA courses in TEFL. His courses of interest are teaching methodology, practice teaching, and teaching language skills. His research interests are teacher education and reflective teaching. E-mail: r.rayati@umz.ac.ir and alirayat@yahoo.com

Menu

Abstract

An Investigation to the Effects of Unseen Observation on Language Teachers’ Behavior Associated with their Classroom Talk

Research questions

Reflective teaching

Stage 1. Pre-training

Stage 2. Professional education/development

GOAL: Professional competence

Unseen observation

Background to the study

Methodology

The interviews

Participants

Data

Data analysis procedure

Analyzing the data

Answering the research questions

Discussion

Implications

Research Limitations

References

Traditional form of classroom observation has been carried out with diverse purposes. The major problem with this form is its interventionist nature; it prevents teachers and students alike from showing their natural everyday behavior. To remedy this problem, unseen observation has been assumed, in the current study, to pass the duty of observation from the observer to the teacher. Four novice teachers were interviewed, both before and after their teaching events; the interviews were audio-recorded and later transcribed and analyzed in order to examine to what extent they become responsible for observing their own classes as a result of unseen observation. Results indicated that the course of unseen observations failed to contribute to the participants’ improvement in their career. Implications are discussed.

Observation as a tool for teacher development offers a very promising perspective. The activity has, almost always, taken on the form of an external person, who may be a supervisor, a more experienced teacher or a colleague, attending a teacher’s class trying to focus on specific area of the teacher’s teaching practices which manifests itself as a problematic element in the class. S/he comes to the class, sits in the least disturbing place inside the class and tries to be as quiet as possible during the class time. Once the class comes to an end, the observer and the teacher undergo a discussion through which s/he provides his/her ideas about what s/he witnessed in the class which may later be used as ground for the teacher’s behavior change.

Despite the benefits observation provides for teachers and other stake-holders alike, observation is usually associated with a number of shortcomings. The very first of them is the fact that the teacher and the students alike are unlikely to show their every-day activities and performances when there is someone who, they think, is looking at them with a magnifying glass. Another problem with this approach to classroom observation is that in most cases observers often tend to pass value judgments on the teacher’s manners of teaching.

As a consequence of the problems associated with the traditional form of doing observation, one solution appears to be what has been called “unseen observation” introduced by Rinvolucri (as cited in Quirke, 1996). A typical unseen observation includes the teacher’s filling out a questionnaire involving items focusing on a specific area. This will help the teacher raise his/her awareness about that area. It is followed by actual teaching; the teacher enters the class and starts teaching, with his/her awareness arisen. After the class ends, the supervisor, peer or the colleague enters into a conversation with the teacher about his/her behavior on that particular area, relying on the teacher’s account of the event. What follows next is more like the steps in other forms of observation; they negotiate their perspectives and later changes in behavior may occur.

What seems to be the most promising point with an unseen observation is the fact that no outsider enters into the classroom. This will delete out the unwelcome consequences of his/her attendance in the class. Another improvement may be that through unseen observation the channel for passing value judgments is closed down. Furthermore, it may help the teacher take on a more independent role regarding his/her own development.

The present study which is of an exploratory nature makes an attempt to find out if unseen observation can be beneficial for English teachers or not. It will be carried out in the context of Iranian teachers, most of whom either have not been to any teacher education course, or if they have been, they have not been made familiar with the benefits of observation or self observation. The type of in-service programs set up for Iranian teachers are mostly what Wallace (1991) terms “crafts model” (p. 6), or what Schön (1983) refers to as “technical rationality” (p. 21), with little attention being paid to the more promising approach, the reflective approach. Therefore, it seems quite obvious that Iranian teachers need help and support of more knowledgeable agents to improve in their career.

Regarding the above account the research questions for the present study are posed below:

- Does Unseen observation have any effects on teachers in motivating them to adopt a critical position towards their teaching behaviors associated with their classroom talk?

- Does Unseen observation contribute to the creation of a state in teachers in which they feel as if they are being observed during teaching while they are not actually?

The origin of this concept is attributed to Dewey’s writings in 1933. He defined reflection as “turning a subject over in the mind and giving it serious and consecutive consideration”, thereby enabling us “to act in a deliberate and intentional fashion” (as cited in Freese, 1999). It is an approach to teacher education which emphasizes reflective action over routine action. In this approach the teacher is encouraged to put his/her current practices, beliefs behind them, and probably covert, reasons why s/he does them under critical reflection. This will lead to the teacher’s increased awareness of his/her own beliefs and philosophies, which may help his/her find justifications for his/her personal behavior or discard them in favor of more appropriate ones. This cycle of reflection on practice is a continuous one with reflection resulting in the formation of new practices which are themselves later reflected upon. The final outcome of this process is the accumulative gain in professional expertise. As is apparent here, this approach does not believe in one-shot attainment of the goal, as is the case with what Wallace (1991) calls the “Crafts model” or Schön (1983) terms the “Technical rationality” of educating professionals; rather it sees the achievement of expertise as happening over time.

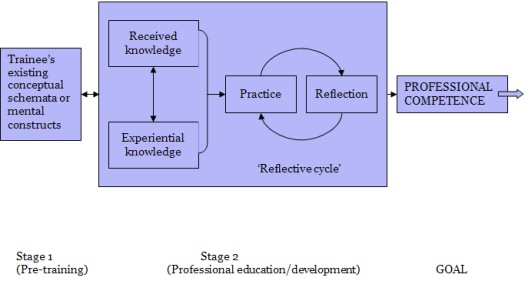

The model of reflective teaching acknowledged throughout this volume is Wallace’s (1991) model a presentation of which comes here. This model comprises three levels: stage 1. pre-training, stage 2. professional education/development and 3. GOAL.

Figure 1. The reflective practice model of professional education/development. (from Wallace, 1991, p.49)

This stage is the one which the trainee is at just before he starts his developmental activity. This stage, therefore, makes an attempt to account for a teacher’s existing ideas and philosophies. The inclusion of this stage aims, according to Wallace, to “…emphasize the fact that people seldom enter into professional training situations with blank minds and/or neutral attitudes” (p. 50).

Two types of knowledge are distinguished in this stage; the received knowledge and the experiential knowledge. The received knowledge comprises those beliefs, attitudes, known facts and pieces of information that the individual receives from other agents regarding a certain subject matter. On the other hand, experiential knowledge is those beliefs or attitudes that a teacher develops as a result of his engagement in actual teaching.

What lies at the heart of reflective approach to teaching is the relationship between these two types of knowledge. This relationship is in the form of reflection on both types of knowledge which leads to the identification of one’s own tacit knowledge or modifying the existing ones into new and more suitable bits of knowledge. The aim is to discover one’s own hidden philosophies and find better ways of doing things. This reflection can be before the event, during action known as “reflection-in-action” or after the event, “reflection-on-action.”

Wallace’s concept of goal sees competence as a starting point, a point of departure towards horizons that will be followed in one’s professional life, but never arrived As such, it sees the professional in general and the teacher in particular in an on-going and never-stopping process of development.

The idea of unseen observation originates from J.L. Moreno’s psychodrama during 1920s in the field of psychotherapy. In a psychodramatic approach to treating patients, they are requested to role-take in a drama along with other patients; then they are requested to show their spontaneous feelings to a particular subject they confront on the stage. This procedure of treatment is used to find solutions for past and present or maybe future problems. Psychodramatists believe that in this way a patient may pour out his/her inner crises, feelings, passions, etc.

It is the idea behind psychodrama that may have given rise to this form of observing teachers; i.e. relying on the individual’s own accounts to gain access to and dealing with his/her problems. This methodology may look much like body treatment by physicians, who do not enter into the patient’s body, relying on what he provides them as a description of how he feels and of what part of his body has problems. Likewise, in an instance of unseen observation the other party does not go into the class, and relies on the teacher’s account of classroom events as a basis for later discussions and feedback.

In the earliest days of the field of applied linguistics the main preoccupation was with devising aptitude tests. The concern with such tests was soon criticized for the selective nature of these tests, and later changes in the scientific and technological atmosphere of the world resulted in the shift of attention being turned from aptitude tests to teaching methods, along with a requirement for researchers to bring forward scientific rigor to their claims. The prominent tool, on which the studies associated with such thinking were based, was observation. Examples for these researches are Keating’s 1963 study of the effectiveness of language laboratories and (Smith, 1970), known as the Pennsylvania Project Report, which aimed to prove the superiority of the audiolingual method. This was the first appearance of observation.

Another research tradition that was emerging simultaneously with the above researches was the one which built observation as the major research procedure. This inclination to doing researches utilized observation as the tool for gathering data of the actual classroom behavior of the teachers. What was common among them was the researchers’ reliance on observation as the tool which would enable them to record what teachers did in classes and make micro-comparisons between the ideal behaviors and the current ones, as opposed to macro-methodological comparisons. One example of a research in this tradition was Jarvis’s paper (Jarvis, 1968). Politzer, also, published his paper in 1970 in which he attempted to find out good vs. bad teaching behaviors. He was “…concerned with validating particular teaching techniques which happened to be quite narrowly associated with a particular teaching method” (Allwright, 1988, p .34).

Rothfarb (1970) attempted to investigate the effectiveness of teaching language at her time. Her paper, at first, seemed to offer a descriptive picture of local practices. She started out by the assumption that practice that revolves around oral skills yields the maximum benefit. Thus it can be deduced from her assumption that although she claimed to be engaged in descriptive study, her work was prescriptive in basis and was not much different from Jarvis’s and Politzer’s works in this regard.

This preoccupation with observation as a research design was not the only view of it. Another group of researches took it to be used in an entirely different approach: that as a feedback tool for training teachers. The intent was for observation to make valid, objective and to-the-point recordings to be utilized for giving appropriate feedback for teachers which later would result in behavior change on the part of the teacher. Example is Moskowitz’s 1968 paper in which he preoccupied himself with securing behavior change through the provision of accurate and relevant feedback. Similarly, Grittner in 1969 in a book titled “Teaching Foreign Languages” took the same idea of observation and set out to instruct student teachers to make self-observations using Nearhoof’s observation system.

Early 70’s were the years which witnessed gradually increasing doubts and objections to Flanders and his observation systems. Bailey, for example, in 1975 expressed her doubts over the categories involved in this system, their practicality, interpretation and time requirements. Rosenshine in 1970 made objections to the entire procedure, stressing his disbelief in dislocated zeal in Flanders’s claim to have found a relationship between teacher behavior and learner achievement. These objections resulted in the emergence of some alternatives to Flanders’s system. One of these alternatives was offered by Fanselow, (Fanselow, 1977), who attempted to bring uniformity to the field of applied linguistics by introducing a system which could be used by everyone in the field. In 1976 Long and his colleagues, impressed by Barnes’s work who was interested in language use among learners for learning, started their study which aimed to ‘explore’ the structure of group work. They started with systems like Flanders’s and Moskowitz’s and finally proposed their own system, the ‘Embryonic Category System, (ECS).’

Up to this point observation has been used for diverse purposes with the main purpose being as a research design. However, as Allwright (1988) sees it, it lacked a focus. He points to the fact that observation had a location and a general procedure for doing researches, the location being the language classroom and the procedure being to look at classroom events. What observation, for Allwright, lacked was the absence of what to look for in class. It was at this point that a number of inter-disciplinary studies, notably the field of second language acquisition, emerged. Therefore, observation borrowed the focus from these disciplines and was used to carry out SLA researches. Allwright’s own study (Allwright, 1975) of learner errors, Gaies’s (1977) work on teacher talk as input and Seliger’s 1977 paper on learner interaction can be mentioned as examples, and this procedure continues today.

The uses of observation described up to now were as diverse as methodological researches to SLA researches. However, the view of observation as a tool for teacher development is not as old as these studies. Although Rothfarb (1970) points to the merits of observation for teachers in their professional growth, and although Krumm (1973) points to the necessity of building observation training in teacher education courses, the atmosphere in which these studies were carried out was not so much concerned with teacher development as it was with the purposes mentioned earlier.

Nevertheless, researchers in other fields have explored the role of self observation or self assessment on an individual’s behavior. Ross and Bruce (2007), for example, investigated the effects of the provision of self-assessment tool on the changes of a mathematics teacher’s behavior. They found that its provision contributed to the teacher’s growth by (1) influencing his definition of excellence in teaching, (2) helping him select improvement goals by providing him with clear standards of teaching, (3) facilitating communication with the teacher’s peer and (4) increasing the influence of external change agents on teacher practice.

Montgomery and Baker (2007) investigated the effects of teachers’ self assessment on their written feedback and on learners’ perception of this feedback in writing in an intensive English as a second language program. They found that the teachers’ self assessment and their actual performance of giving feedback did not match well.

Bailey (1990) cites some studies of teacher diaries as the tool to probe into their behavior. She cites Deen’s (1987) diary study of her own diaries as she taught a project-based course in Dutch at the same time that she was taking a graduate seminar on project-based language teaching. Her diary study combines her own observations about the course with written comments from the professor of the graduate seminar. Bailey also cites Ho’s (1985) study on the use of English and/or Chinese to teach remedial English classes in secondary schools in Hong Kong in order to investigate the teacher’s actual feelings and frustrations experienced in making the language choice.

Quirke (1996) conducted a study in which he trained a number of teachers on the use of unseen observation, and attempted to investigate the effectiveness of such training on the teachers’ behaviors. He reports an effect for his instruction. But his paper suffers from a number of methodological shortcomings. The first, and to me the most outstanding, of which is the lack of an appropriate tool for measuring the effectiveness of his training, a shortcoming which will be dealt with in the present study by interviews which will focus on the exact activities the teachers implement. Quirke used his own observation of the post study behavior of his participants and in some instances their personal impressions. But he does not make it clear that how these behaviors were results of the instructional part of the study. Furthermore, in reporting the effects of his instruction, he reports activities that bore no relevance to in-class teaching. However in a later study he used the same name, i.e. “unseen observation” for a form of observation which was radically different from that of his 1996 study. In it he captures the learners’ perspective and their ideas regarding the teacher’s teaching in order to “…come a little closer to understanding what was happening in these specific learning contexts.” (Mizon & Quirke, 2000, p. 4). But as stated earlier the methodology used in this study was different from the one adopted in his earlier study and also adopted in the present study.

The present qualitative research has adopted a case study design to probe into the behavior of the participants. The number of participants of this study, i.e. four, may seem contrary to the title of “case” studies; however, Mackey & Gass have allowed for “…more than one individual learner or more than one existing group of learners”, (p. 172), to be used in such a study.

The interviews were the friendly conversational events during which the researcher carried out discussions with the teachers. (The terms “interviews” and “discussions” are used interchangeably and mean the same throughout this volume). The discussions focused on the topic of “teacher talk” and were held in Farsi. The structure of the interviews, as proposed by Quirke (1996), was as follows: pre-course interview, pre-lesson interviews, feedback interviews, post-course interview.

Pre-course interview, which was hold before the course started, to give a general picture of the aims of the study to the teachers.

Pre-lesson/feedback interviews, which were three-time pairings of interviews held both before and after the actual teaching events, to raise teachers’ consciousness (before), and to help them remember, post facto, what happened in the class (after). Discussions were based theoretically on Amy & Tsui’s (1995) approach to teacher talk.

Post-course interview, held after the course to solicit the teachers’ impressions of and suggestions for the improvement of how the interviews would better be held.

The participants for this study were 4 teachers, aged between 20-25, two of whom were male and the other two of whom were female. They were teaching in an institute in Babolsar, Iran. Three of the teachers were senior students of English and one was a senior student of economics, in the University of Mazandaran, Iran. The teachers had the experience of teaching for 1, 3, 4, and 5 years prior to this study, therefore, they can be regarded as less experienced teachers. The element of experience is an important consideration, since, as Cosh (1999) quotes Lortie , the teachers’ own experience is more important than the training they receive in their development and less experienced teachers are more willing to engage in such development.

The data utilized for this study were the transcriptions made of the audio-recorded discussions held between the researcher and the teachers. Each discussion was recorded and later transcribed. The number of transcriptions for each teacher was 8, with the total number of 32. The total lengths of the interviews for each teacher varied between 120 to 140 minutes, culminating in nearly 520 minutes of recordings in sum.

The data analysis phase of the study was not a one-shot event. It took place during a process of recording, transcribing and analyzing and re-analyzing after the second round of transcribing and this cycle continued until the very last interview of the course, the post-course interview. This manner of data analysis, therefore, seems to be an inductive, top-down way of approaching the issue, a manner which Corbin and Strauss call “immersion in the data”, (Corbin & Strauss, 2008, p. 46).

Teacher no. 1

This teacher, seemingly, benefited from unseen observations, although not substantially. This claim, as to the insubstantial change in the teacher’s teaching practices, can be supported by two reasons; one is the lack of any evidence, either observed or reported, of a thorough change in the teacher’s behaviors. The second reason is the teacher’s own statement in the post-course interview:

T: I had tried new things. I had some inputs, but no output, [I had no discarded behavior]. It means that I believe in my past behaviors. For me, and if we look at the reasonings I gave in the interviews, my ways are right. But it is natural if I want to add to or cut from them. (eighth interview)

In contrast to his statement in the post-course interview, teacher no. 1, however, appeared to indicate minor signs of improvement during the weekly progression of the course. After the first feedback interview, the teacher displayed no token of any possible change or reflection taken place after the corresponding pre-lesson interview. At the start of the interview the teacher stated:

R: What happened to your teaching after we talked about teacher questions?

T: Well, the procedure was our routine system, with the same events; like asking questions for starting and … (third interview)

This very statement reveals that the first interview and its agenda did not appeal to the teacher and, consequently, that he followed his own teaching predispositions. Elsewhere in the same interview, his manner of responding to questions that were mostly in the format of ‘Did you pay attention to …in the class?’, was in such way that as though the researcher was making a question to obtain his ideas, despite the fact that such responses had already been received in the pre-lesson interview. To illustrate the point look at the following extract:

R: Did you pay attention to the questions you asked in different points of class time?

T: Of course. I told you before. Sometimes I ask pre-made questions… This is one aspect of my questions. Even some cases show up in which I have to … (third interview).

The question made by the researcher requires either a “yes” or “no” answer. If the former was the case, then the teacher would express the ways through which he had been pre-occupied with the issue. Apparently, uttering responses that resemble more to be answers for questions in the format of ‘Have you paid attention to … in the class?’ – questions made in the pre-lesson interviews – points to the fact that the latter of responses i.e. “no” is the case here. I refer to this kind of responses as ‘re-stated responses’ – responses already made in the pre-lesson interview – throughout the rest of the present volume, for ease of reference, since this kind of responses made by the teachers are many.

The third interview, also, bore little signs of changed behavior or any attempt at ameliorating them. The teacher’s responses, again, were mostly of the ‘re-stated’ type. The most noticeable instance of disregard to the pre-lesson questions is obvious in the following extract:

R: Did you notice if your explanations engaged the learners or not?

T: Uuuuh

R: No?

T: Not no. The answer is never ‘no’. I can’t say “yes”; I can’t say “no”, either… (seventh interview)

However, the teacher again stated that the alternatives provided by the researcher were running through his mind during his teaching. But the observable result of this awareness is none.

During the post-course interview the teacher mostly implied the awareness raising property of unseen observation, as was the case with the second and third feedback interviews discussed above. The accounts he provided during the progression of the course of unseen observation revealed little signs of any movement beyond raising his awareness as a result of the interviews. Therefore, it can be claimed that the course of unseen observation resulted in raising the teacher’s awareness, only, and no accompanying behavior change took place for him.

Teacher no. 2

She was a young teacher and also a senior student of English literature. She was teaching for a few learners as a private tutor.

Teacher no. 2 manifested little signs of the effects of unseen observations. This claim can be supported by the teacher’s lack of interest in the questions asked in the interviews. This lack of interest could be detected during the progression of the interviews. We now turn to this point.

In the first feedback interview the teacher’s statements revealed that the questions asked in the pre-lesson interview were not successful in attracting the teacher’s attention. The following extract illustrates an example taken from this interview:

R: The few questions you asked, did they attract your attention?

T: My own attention?

R: Yes, I mean you may pay more attention.

T: Yes.

R: Did you draw any specific conclusion?

T: No. Not a specific conclusion. (third interview)

Although the teacher gives a “yes” answer, what follows can be an indication of otherwise, i.e. “no”, since if she had been interested in the questions, she could have provided more details and also she could have expressed her impression of the questions raised during the interview.

The second feedback interview included one instance of changed or improved response. In the pre-lesson interview the teacher in response to the question of “Do you attend to the grammar or content of the learners’ responses?” had stated “I don’t know.” However, she stated in the feedback interview that it is to the grammar of the learners’ responses that she attends to. Nevertheless, the second feedback interview also included instances of unchanged responses. For example:

R: What did you do with correct utterances?

T: If it was a two-way discussion, I didn’t make any interruption. (fifth interview)

This was exactly what she had stated in the pre-lesson interview, with no further details.

Although at times little signs could be detected which referred to the minor effects of unseen observations in the teacher’s behavior, overall, as the evidences indicated above, the observations failed to create in Teacher no. 2 the eagerness to reflect on the contents of the questions asked in the interviews.

Teacher no. 3

Teacher no. 3 appeared to make little benefit from the course of unseen observation. This claim can be supported by what he stated in the feedback interviews. We now turn to the analysis of the weekly progression of the interviews.

In the first feedback interview he expressed his deep satisfaction with the last teaching event before which the pre-lesson interview was held. He reported using a particular type of questioning which resulted in an active class atmosphere. When asked for the motive behind this change of behavior he answered:

R: Why, do you think, your class was different? What element created that atmosphere?

T: Look…For one thing, it was for the second or third time that I was teaching the point. Also, these interviews were effective. (third interview)

The teacher claims to be influenced by the interviews. This is the most significant point in the first feedback interview.

During the second feedback interview he manifested almost no sign of the effects of unseen observations on his behaviors. The following piece of extract illustrates the point:

R: Did you correct immediately or after delays?

T: No … There were no delays. It depends on …, no delays. I repeat the learners’ utterances to see what they say.

R: I mean, is there always a delay?

T: Yes, always. I don’t correct immediately. (fifth interview)

Two points can be raised regarding this extract. The first is that the teacher makes contradictory statements in response to the repetition of the same question, i.e. “no delays” and “I don’t correct immediately”. This points to the teacher’s spontaneous thinking during the interview, which implies lack of thinking about the questions before the interview. The second point is that his statements are of the “re-stated” type of responses, which I explained earlier. This type of responses refers to the teacher’s failure to notice the agenda of the interview during his teaching time or after it.

The teacher in the third feedback interview also appeared not to benefit from unseen observation. Take, for example, the following piece of extract:

R: Did you pay attention to what you did to make your explanations comprehensible?

T: Yes, I told you. Maybe I would say I do many things, body language and examples. (seventh interview)

The teacher’s response is of the “re-stated” type. He, most probably has not been influenced by the agenda of the interview.

Overall, Teacher no. 3 exhibited little signs of progress as a result of the unseen observations. Except for the first feedback interview during which he reported a minor change in behavior, the rest of the interviews pointed to the failure of the interviews to motivate the teacher towards reflection.

Teacher no. 4

From the very first feedback session – third interview – teacher no. 4 manifested signs that she had been engaged in a reflection on her practice. During this interview she stated that she had changed her manner of asking open ended and close ended questions. Look at the following extract taken from this interview:

T: …Unlike before, this session I told complete sentences and then asked “Am I right?”

R: Why did you do so?

T: The last time you asked me if I ask open or close questions. I thought about it. If I ask close questions, that would be some sort of input for the learners, because they had many grammar errors. I wanted to fill their minds, indirectly, with the correct form….I asked them 8 or 10 times and didn’t give them much time. They gave short answers. Then I felt they learned some minor grammar points. (third interview)

In response to the same question of close-open questions the teacher, in the second interview, had firmly expressed she did not give much stress to close ended questions because of the limited scope of the answers they require. She believed, rather, in more open questions, which require longer stretches of discourse. Below is her actual statement:

R: Have you noticed where and when you usually use open or close questions?

T: To tell the truth, I don’t really rate close questions so much; because they are gone by a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’, and no communication follows them. So, when I ask an open question and he gives a short answer, I ask it another way or prolong it somehow. (second interview)

Compared to what she had stated in the previous interview, the former extract is a clear evidence of the teacher’s disbelief in her former ideas, and of her trial of an alternative course of action. This changed behavior is the first sign of the success of the unseen observation in triggering reflection in the teacher over her behavior.

The teacher also exhibited another occasion of reflection in the second feedback interview. In this interview the teacher revealed her reflection over why her learners made errors. The following extract shows this point:

R: Did you pay attention, while you were teaching, to the topics we discussed in the last interview? Did they interest you?

T: I thought about why some children misplaced some points in their work book. Most of them were on grammar. I thought about why they make so many errors. I don’t know. Did I not explain grammar well? Then I looked at their work book, and saw things that were new in it, which were not in their student book, like the word ‘jewelry’. If a child has not seen this, of course he will make an error on it. (fifth interview)

The teacher’s movement towards reflection could also be documented in the third feedback interview. The teacher, again, reports a change in her behavior, regarding the way she presented a listening passage. The following extract illustrates this point:

R: Did you pay attention to your explanations of the points in the page?

T: Well, I got one. I first let them listen. I explained the meanings of words as they came…I used to tell their meanings before the activity, but this time didn’t. I told them just to listen and fill in the blanks. I didn’t give the meaning of the passage, either. I put it for them. They could tell some shade of the meaning. Then I used synonyms. This way I gave them some time to engage.

R: Why did you change your way?

T: Well, we talked about student engagement the last session. I changed my way to see if their engagement got any better. (seventh interview)

The final instance of the teacher’s change in her beliefs and consequently in her behavior could be detected in the post-course interview. The following extract captures this point:

R: What is your evaluation of this project? Did it help you improve your teaching?

T: Yes.

R: How did it help?

T: The first thing was that, if a child doesn’t want to or is tired, [sic]. I used to think that it is my duty to tell it all, to explain everything. But there were times that I could see they were tired and my explanations had no use other than just making myself tired. So I decided to cut extra parts out; to talk less. This is what I thought about. I used to believe that we are supposed to explain, even if they don’t want us to. I saw myself talking for 20 minutes, but nobody would listen. Even they wanted me to stop. So I changed my mind. From now on I will explain the important parts, and if they don’t want me to, I will stop. But I will go on if just of them wants. (post-course interview)

The teacher’s comments are related to creating interest in teacher explanation and thus correspond to sixth and seventh interviews, during which the agenda included teacher explanations. But as was mentioned above, she pointed to her change of practice regarding student engagement in the seventh interview, and, therefore, was planning for this change in the time lag between sixth and seventh interviews, and it was after the seventh interview that she focused on securing interest in teacher explanation. It was a time when both pre- and post-lesson interviews related to teacher explanation had already been held, and she was not required, from the researcher’s part, to re-focus on her explanations. Therefore, it can be said that the last of the changes the teacher made in her behavior, was purely self-initiated. This self-initiated behavior, seemingly points to the interest the course of unseen observations had created in the teacher.

Another point which can be made regarding the teacher’s reflection and changed behaviors is that, the amount of teacher reflection increased with time for this teacher. This can be claimed from the number of instances of reflection the teacher displayed after feedback sessions; after the first two feedback sessions she displayed one instance for each, but after the third feedback interview, she displayed two instances. This can be a good evidence for the increase in the extent to which the teacher engaged in reflection as the course proceeded.

Overall, teacher no. 4 appeared to benefit from the course of unseen observations. She manifested signs of reflection from the first feedback interview onwards. The amount of reflection was more at the final stages of the course than the earlier ones for this teacher.

First research question: Does Unseen observation have any effects on teachers in motivating them to adopt a critical position towards their teaching behaviors associated with their classroom talks?

Two of the participant teachers in this study appeared to adopt a critical position, as a result of unseen observation, towards the way they have had used teacher talk in class. Teacher no. 1 reacted in a way that his awareness was raised due to the discussions held during the interviews. Teachers no. 2 and no. 3 did not display a noteworthy reaction to the course of the observations, with no reflection and no change of behavior. Teacher no. 4 displayed a type of reaction which included awareness raising, reflection and change of behavior.

The display of reaction is emphasized here, because it is not acceptable to expect to have fully-reflective teachers at the end of the course of unseen observation, and the provision of a stimulus is sufficient for the success of this work. One may argue that the provision of a stimulus for a course of interviews may be an insufficient criterion for its success. However, the point with such a course is that it is a developmental activity as are activities like journal writing, action research, writing lesson reports, etc. which Richards and Lockhart (1994) mention for a reflective teacher. We cannot expect of a teacher who has carried out an action research to come to a full understanding of his teaching. Likewise, in the present study, the expectation was not to have teachers with perfect manners of teacher talk at the end of the study, gained as a result of reflection on the concept. Rather professional competence, as Wallace says:

“… [is] a moving target or a horizon, towards which professionals travel all their professional life, but which is never fully attained. …professional certification (in whatever form it might take) is not a terminal point but a point of departure” (Wallace, 1990, p. 58).

Among the elements that contributed to the display of diverse reactions to the interviews on the part of the teachers are the teachers’ personalities, their intellectual inclinations, and the contexts of the interviews; the proceedings of the interviews with the same topic are certainly different for different teachers and these differences may obscure the effects the interviews may have on the teachers.

To bring forward a response to the first research question it can be claimed that unseen observation does not have similar effects on the behavior of different teachers. The participants did not react in similar ways to the course of unseen observation. Two of the participants appeared to benefit from the merits of unseen observation, while the other two failed to display such reaction. Therefore, the present study suggests that unseen observation, depending on different variables, produces different results; and that it is the duty of future line of research to investigate what these variables are.

Second Research question: Does Unseen observation contribute to the creation of a state in teachers that they feel as if they are being observed during teaching while they are not actually?

The principal problem with observation as mentioned earlier, is the “other’s intrusion”. Consequently, unseen observation is one attempt to counter this problem by removing the observer from inside the class and putting him/her out of the class, and still providing him/her with necessary means to observe the class. The chief of such means is the teacher’s report of the class. The teacher after the class reports to the observer and through the ensuing discussion they exchange ideas. One point with this discussion is that provided that certain conditions are met, such as teachers’ willingness, significance of the topic chosen, the friendly nature of the observer-teacher relationship, they are likely to create in teachers a feeling that they are being observed by someone while they are teaching, though they are not, actually. Once this feeling is created, much of the work has been done, since as long as such feeling presides over the teacher’s practice, the situation resembles to an occasion of traditional form of observation, but without its negative consequences.

The participants of this study manifested no signs of the creation of the feeling described earlier. Although the teachers were not asked directly during the recorded interviews whether such a feeling had been created in them – since the response to such a question is apparent: a “yes” – the off-interview conversations between the researcher and the teachers revealed that such a feeling had not been created. The reasons may be many. The most probable of these reasons, which explains the failure of the interviews to create such a state in teachers, is that they were not volunteers to take part in unseen observations. They were not reluctant, however. In other words, the researcher asked for their participation, and they agreed to participate. So, the teachers’ motive to keep with unseen observations may be much punier than a hypothetical volunteer who takes part in unseen observations based on personal desire. Other reasons, though possibly less significant than the one just presented, may be put forward such as the timing of the interviews, the topic (i.e. teacher talk), and so on. But to the present researcher their impact was not very strong.

To close the discussion on the findings for the second research question, the following answer to this question is provided:

Unseen observations failed to create in teachers the sense that they are being observed by someone while they are teaching, when there is no observer in the class, actually.

Reflective teaching is marked by adopting a critical position towards one’s own teaching. “Reflective teaching will make teachers question clichés they have learned during their early formative years…” (Akbari, 2007). Any activity that helps teachers engage in the reflective cycle is an invaluable tool to promote reflective teaching. In the present study unseen observation is hypothesized to be such a tool and the account to be presented below discusses the results of trying this tool with the participant teachers in this study.

The teachers in the present study displayed varying reactions to the course of unseen observation. Teacher no. 4, in particular, manifested a movement towards reflection as a result of the interviews held during the course; a movement which can be marked by changed behavior, trial of other and novel choices of action, craving to know more about her teaching and in- and out-of-class reflection over the issues raised during the interviews. Teacher no.1 came to a position, due to the interviews, in which his awareness of the different behavioral alternatives regarding his classroom talk was raised, with little or no changed behavior. Teacher no.2 and no.3 exhibited almost no sign of the effects the course of unseen observation may have had on their behavior. This variation in the results of the study may be attributed to contextual factors like time and place of the interviews, as well as to the teachers’ personal characteristics,

There appear to be some shade of discrepancy between the results of the present study and the one conducted by Quirke in 1996. Besides reporting the teachers’ satisfaction – which was a shared finding between the two studies – Quirke reports a number of more adventuresome activities from the part of his participants than what were observable for the participants of this study. Examples of these activities are leaving their own country, i.e. U.A.E. for the U.K. to take an M.A. in TEFL and initiating a diploma in TEFLA. This mismatch between the results may be attributed to two factors; one is the duration of the course of unseen observation. Quirke’s study took 9 months, while this study took only 2 months. The length of the course, certainly, is a determining factor, since a longer time is accompanied by more amounts of reflection, and consequently, by more development made, which may encourage more future developmental measures.

Another, but not less significant, explanation for the different findings of the two studies is that in Quirke (1996) the student teachers worked with the collaboration of a teacher trainer, i.e. the researcher himself. The present researcher, on the other hand, was a M.A. student whose superiority over the participants, in terms of knowledge of the subject matter, was related only to his readings on the subject of Teacher Talk, but who lacked the skills required for a teacher trainer, which, otherwise, would have enabled him to make up and pursue a more fruitful relationship than the one he established in this study. However, the improvement of this study over Quirke’s is its precision on the criterion for success of the work and the procedures that build such an assertion of success.

It was discovered that unseen observation has the potential to be utilized to assist a reflective teacher go through the “reflective cycle” of Wallace’s model, (Wallace, 1990), although it did not appear to be as useful as the techniques Richards and Lockhart (1994) mention as possible ways of probing into one’s own teaching, like journal writing, action research, peer coaching, teaching portfolios. Teachers can exploit the benefits it provides to improve their teaching. Since teachers may be dubious about or unaware of its merits, if they are left to their own resources, teacher education courses can build such observations into the make-up of their courses and give help to less experienced teachers on how to implement them and how to provide a focus for the activity to maximize the gains. Language schools and institutions alike can also foster undertaking this activity among their staff, with subsequent rewards or promotions for those who engage.

However, caution must be exercised in considering unseen observation a replacement for the traditional form of observation. Such a stance, for the present researcher, is far from being realistic. Unseen observation with the specific design adopted here is purely for developmental purposes, and at this state of knowledge, it seems, it cannot fulfill the other purposes that the traditional form can, purposes like staff appraisal, evaluation, giving feedback to teachers, assessing learners’ behavior, etc. even for development, unseen observation is not meant to replace its predecessor form. A teacher may feel more comfortable with observation with the traditional form than with the unseen form, and this preference should be respected and prioritized. As such, unseen observation is not a replacement; rather, it is an alternative, a complementary technique to other techniques of engaging in reflective action.

The first setback of this study was the timing of pre- and post-lesson discussion. In most cases there was a time lag of 2 or 3 days between the time which was most suitable for the discussions and the time of the actual discussions. It would be the most favorable timing if the pre-lesson discussion immediately preceded the lesson itself, and if the lesson was followed immediately by the post-lesson or feedback discussion. But for exactly the same reasons as mentioned above the organization of the interviews inside the institute was impossible and, consequently, an arrangement was made to hold them in the university where the teachers were studying. However, maximum effort was made to approximate the discussion time to those of the interviews.

Another deficiency of the present study might be the uniformity of the topic. That is to say that if the participants were allowed to choose a topic of their own interests, better results would be achieved. However, for the purpose of the uniformity of the data to make easier-to-understand interpretations, the topic of “teacher talk” was chosen by the researcher.

Akbari, R. (2007). Reflections on reflection: A critical appraisal of reflective practices in L2 teacher education. System, 35, 192-207.

Allwright, D. (1975). Problems in the Study of the Teacher’s treatment of Learner Error. In Allwright, D. Observation in the Language Classroom (pp. 198-213). Longman: Longman Group UK Limited.

Allwright, D. (1988). Observation in the Language Classroom. Longman: Longman Group UK Limited.

Amy, B., & Tsui, M. (1995). Introducing Classroom Interaction. Penguin English.

Bailey, K.M. (1990). The use of diary studies in teacher education programs. In Richards, J. C., & D. Nunan, (eds.), Second Language Teacher Education (pp. 215-226). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bailey, K.M. (2001). Observation. In D. Nunan, & Carter, R. (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to teaching English to speakers of other languages (pp. 114-119). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bailey, L. G. (1975). An Observational Method in the Foreign Language Classroom: A Closer Look at Interaction Analysis. Foreign Language Annals, 8(4), 335-344.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of Qualitative Research. Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. California: Sage Publications, Inc.

Cosh, J. (1999). Peer observation: a reflective model. ELT Journal, 53(1), 22-27.

Deen, J. (1987). A teacher’s diary study of an experiment in project-based language learning. Unpublished manuscript. TESL master’s program, University of California, Los Angeles.

Fanselow, J.F. (1977). Beyond RASHOMON-Conceptualizing and Describing the Teaching Act. TESOL Quarterly, 11(1), 17-39.

Freese, A.R. (1999). The role of reflection in pre-service teachers’ development in the context of a professional development school. Teaching and Teacher education, 15, 895-909.

Gaies, S.J. (1977). The Nature of Linguistic Input in Formal second Language Learning: Linguistic and Communicative Strategies in ESL Teachers’ Classroom Language. In Allwright, D. (Ed), Observation in the Language Classroom (pp. 214-223). Longman: Longman Group UK Limited.

Grittner, F.M. (1969). Teaching Foreign Languages. Harper and Row, New York. In Allwright, D. (Ed), Observation in the Language Classroom (pp. 85-95). Longman: Longman Group UK Limited.

Jarvis, G. A. (1968). A behavioral observation system for classroom foreign language skill acquisition activities. Modern Language Journal, 52(6), 335-341.

Keating, R.F. (1963). A Study of the Effectiveness of Language Laboratories: A Preliminary Evaluation in Twenty-one School Systems of the Metropolitan School Study Council. Inst. of Administrative Research, Teachers College, Columbia Univ.,

Krumm, H.J. (1973). Interaction Analysis and Microteaching for the Training of Modern Language Teachers. IRAL, 11, 163-170.

Long, M.H. (1976). Group Work in the Teaching and Learning of English as a Foreign Language: Problems and Potential. ELT Journal, 31(4), 285-292.

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. (2005). Second Language Research: Methodology and Design. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Mizon, S. & Quirke, P. (2000). UNSEEN OBSERVATIONS, Using the other 40 eyes in the classroom. Retrieved from www.philseflsupport.com/unseenobs_students.htm.

Montgomery, J.L., & Baker, W. (2007). Teacher-written feedback: Student perceptions, teacher self-assessment, and actual teacher performance. Journal of Second Language Writing. 16, 82-99.

Moskowitz, G. (1968). The Effects of Training Foreign Language Teachers in Interaction Analysis. Foreign Language Annals. 1(3), 218-235.

Nearhoof, O. (1969). Teacher Pupil Interaction in the Foreign Language Classroom: A Technique for Self-Evaluation. In Frank M. Grittner (Ed.), Teaching Foreign Languages, (328-340). New York: Harper.

Politzer, R.L. (1970). Some reflections on “good” and “bad” language teaching behaviors. Language Learning, 20(1), 31-43.

Quirke, P. (1996). Using unseen observations for an IST development program. The Teacher Trainer, 10(1), 18-20.

Richards, J.C., & Lockhart, R. (1994). Reflective teaching in second Language Classrooms. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rosenshine, B. (1970). Interaction Analysis: A Tardy Comment. Phi Delta Kappa, 51, 445-446. Reprinted in Sperry, (1972): 246-250.

Rothfarb, S.H. (1970). Teacher-Pupil Interaction in the FLES Class. Hispania 53: 256-260. In Allwright, D. (Ed), Observation in the Language Classroom (35-41). Longman: Longman Group UK Limited.

Schön, D.A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner. How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Seliger, H.W. (1977). Does Practice Make Perfect?: A Study of Interaction Patterns and L2 Competence. Language Learning, 27(2), 263-278.

Smith, P. (1970). A Comparison of the Audiolingual and Cognitive Approaches to Foreign Language Instruction: the Pennsylvania Foreign Language Project. Philadelphia: Center for Curriculum Development.

Wallace, M.J. (1991). Training foreign language teachers: A reflective approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|