Guess, Whose is This?

Efi Tzouri, Greece

Efi Tzouri studied English Language in Greece, specialised in Theatre education and production and has been teaching English for over 16 years. She is board member of TESOL Macedonia-Thrace Association. She loves working with refugee learners. E-mail: etzouri@gmail.com

Menu

Background

Aims

Description

Procedure

Conclusion

References

A lot of studies have been conducted in the field of Methodology regarding the teaching techniques that could be applied in order to build a refugee or migrant educational programme that is devoted to the educational as well as social or psychological needs of these sensitive members of our society who carry traumatic stress and culture shock (Editor, -. P, 2013) in their system. The most important element when we work with refugee young learners is to think a bit differently about how we organize our lesson and what kind of aspects we will decide to pay attention to. Only if our students feel that the classroom environment is safe and protective will they accept new challenges and take the opportunities we give them. “If we can help people feel good about themselves and safe with us, they will be able to learn so much more in the lessons to come.” (FutureLearn).

First and foremost, what is essential is to allow space for feeling and establish a safe environment for teaching by designing a lesson with sensitivity and consideration. We should always give the opportunity to learners to use the language they have been learning through interaction and group work and value learners’ experiences in the classroom. It is effective to design tasks that follow simple instructions, introduce one thing at a time and involve a lot of practice either through repetition (especially for the younger learners) or through role play and communicative activities. Also, it is extremely significant to provide help and support when it is needed, to make sure that everyone is engaged in the activities and participates easily and naturally in communication. Finally, what is more important when we create a task is to take our learners sensitive needs into careful consideration and design material that is based on real life contexts.

This activity aims at fostering self-expression and self-awareness by providing the opportunity to the young refugee learners to introduce themselves to the classroom, to talk about their preferences and to create space for feeling and openness. Additionally, a bridge between personal and school life can be built (Ada &Campoy, 2004) by establishing a safe environment for teaching. Finally, this activity is selected as an ideal one because it promotes group work, enhances multiculturalism, empowers creativity, and develops trust and space for interaction and communication.

Students are asked to bring a personal item in class. The activity can be divided in two parts. During the first part all items are placed in a box. Students do not reveal which item is theirs. Working in groups, their attempt is to guess which thing is whose. In the second part, students are asked to write a story about their personal objects (who gave it to them, why or why they bought it, why it is their favourite, what makes it valuable or important to them, what it reminds them of, where it was bought). Alternatively, they may be asked to write a poem about their object following a haiku format, acrostic poetry or a Grammar Framework poem (Scott Thornbury, 2005).

PART 1 – Guessing

- Students are asked to bring an item in class and they secretly place it in a box.

- Students are organized in groups and they are asked to pick two or three items from the box (the number of objects chosen depends on the number of students in class).

- We instruct the learners to put the items in front of them so that they can be visible to all the members of the group.

- Learners are then told to describe the objects, to ask about vocabulary, to guess whose these things are and to discuss the reasons why they believe these items belong to those classmates.

PART 2 – Self-expression

(In this part items return to their owners).

Story time

- Students are asked to write a story about the objects they brought to class.

- We can give instructions and guide them by posing some questions to consider:

- Who gave it to them?

- Why?

- Why did they buy it?

- Why is it their favourite?

- What makes it valuable or important to them?

- What does it remind them of?

- Where was it bought?

Outcome: They can read the stories in class or teacher can collect them and create a booklet.

Poetry time

Another task that could also be very creative as well as engaging is to ask students to write a poem about their item. It could be either a haiku, an acronym or a Grammar framework poem (the choice depends on the learners’ level). We provide clear guidelines concerning the form of a haiku poem or an acronym poem by giving examples:

Haiku poem: It consists of 3 lines and 17 syllabuses. Each line has a set number of syllabuses:

- Line 1: 5 syllables

- Line 2: 7 syllables

- Line 3: 5 syllables

Example: The sky is so blue.

The sun is so warm up high.

I love the summer.

(Feedback Form, (n.d.))

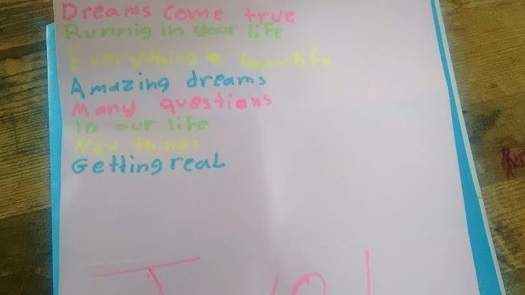

Acrostic poem: Learners can choose a word. It can be the name of the thing they brought to class or one of its characteristics (e.g. colour, shape). The first letter of each line is capitalized (see example below).

OR we give instructions of how to write a Grammar Framework poem:

- article + noun

- participle, participle, participle

- adjective, adjective

- repeat 1

- pronoun + verb

- pronoun + verb

- pronoun + always/never/still + verb

- repeat verse 1

- repeat verse 3

- repeat verse 2

Example

The school

Interesting, fighting, learning

Angry, joyful

The school

I learn

We love

I never scream

The school

Angry, joyful

Interesting, fighting, learning

(this poem is from Jewel Hussein, 10 years old)

Acrostic poem example:

Outcome: We can organise a poetry competition and we could publish the winning poems in the school newspaper/site or create a classroom blog where students’ stories and poems could be posted.

Identifying the current situation of refugee young learners, it becomes clear that it is of great importance to address their needs and to explore ways of helping them become engaged and feel motivated during the learning process. Designing creative activities for children in a multicultural classroom not only “encourages them to connect new information and skills to their background knowledge” (Cummins & Early, 2011, p.4), but also “affirms students’ identities as intelligent, imaginative and linguistically talented” individuals (Cummins & Early, 2011, p.4).

Ada, A. F., & Campoy, F. I. (2004). Authors in the classroom: A transformative education process. Allyn & Bacon.

Cummins, J., & Early, M. (2011). Identity Texts- The collaborative creation of power. Stroke-on-Trend: Trendham Book Publishers, 45-57

Editor, -. P. (2013, December 29). Acculturative Stress Definition. Retrieved July 12, 2017 from https://flowpsychology.com/acculturative-stress-definition/

Feedback Form. (n.d.). Retrieved January 07, 2018, from https://www.youngwriters.co.uk/types-haiku-poem

FutureLearn: https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/volunteering-with-refugees

Thornbury, S. (2005). Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Primary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

|