Elicited Imitation Tasks as Measurement of Language and Working Memory: Evidence from L2 learners of English

Ifigeneia Dosi and Selini Kamoura, Greece

Dr. Ifigeneia Dosi is a lecturer at the Hellenic Open University and a lecturer of Applied Linguistics at level 5 & 6 at the BA (Hons) English and English Language teaching programme of the University of Greenwich which is offered at New York College Thessaloniki. She is interested in bilingualism and language disorders. E-mail: dosi.if@gmail.com

Selini Kamoura is a teacher of English as a foreign language in Greece. She is graduate of the BA (Hons) English and English Language Teaching programmeof the University of Greenwich offered at New York College Thessaloniki. She is interested in second language acquisition and teaching.

E-mail: kamouraselini@gmail.com

Menu

Introduction

Background

The present study

Results

Summary and discussion

References

There has been a long debate whether Elicited Imitation Tasks (EITs) measure linguistic skills, or they are more based on the rote memory skills. Some studies have noted that the role of memory (either working memory or short term memory) is crucial for the performance on EITs (Alloway and Gathercole, 2005; Alloway, Gathercole, Willis and Adams, 2004). Few studies have claimed that the contribution of memory is more important than the contribution of language to EITs performance (Hamayan, Saegert, and Larudee, 1977). Nonetheless, other studies have not observed the impact of memory on the performance in EITs (Okura and Lonsdale 2012, Dosi, Papadopoulou and Tsimpli, 2016). There is however, a great number of recent studies which maintain that EITs draw on both language ability and cognitive resources, primarily from working memory (Riches, 2012; Klem, Melby-Lervaog, Hagtvet, Lyster, Gustafsson and Hulme, 2015), especially when the sentences are quite short (Fattal, Friedmann and Fattla-Valevski, 2011), since language processing is less demanding in short sentences and memory abilities are more possible to affect the participants’ performance (Alloway et al., 2004). Language proficiency also seems to affect the performance on the task (Bley-Vroman and Chaudron, 1994; Munnich, Flynn and Martohardjono, 1994). Limited is the evidence about Greek native speakers, who learn English as a second language (L2), such data would be useful for the educators to plan a more targeted lesson.

The present study investigates the language and working memory skills of native speakers of Greek, who learn English as a L2. Additionally, it also takes into account the aforementioned issues in order to test whether (a) EITs measure both linguistic and (verbal) working memory abilities and (b) language proficiency has any impact on participants’ performance. Hence, in the present study eight participants took part; half of them (n=4) were intermediate learners of English and the other half (n=4) were advanced learners of English.

EITs have been developed and used since the late 1960s, and are considered as a useful tool in first and second language acquisition research. According to this testing method, learners are required to listen to a number of sentences as stimuli, one sentence at a time, and then repeat them as accurately as possible, while researchers record the data for further analysis (Mozgalina, 2015; Slobin and Welsh, 1968). Slobin and Welsh (1968) along with other researchers of the field, argue that EITs are methods for assessing learners’ linguistic competence in the target language (Jessop, Suzuki and Tomita, 2007; Vinther, 2002). Many researchers focused on different aspects of language acquisition, such as implicit and explicit knowledge (Erlam, 2006), global proficiency (Bley- Vroman and Chaudron, 2013) and oral proficiency (Jessop, Suzuki and Tomita, 2007). Others, on the contrary, argue that EITs are more based on memory capacity, rather than pure language skills (Jessop, Suzuki and Tomita, 2007; Hamayan, Saegert and Larudee, 1977).

EITs are considered as a useful tool for measuring general language abilities (Ellis 2005, Erlam 2006), since they depict learner’s implicit knowledge (Marinis and Armon-Lotem, 2015). EITs have been used as an assessment and a diagnostic tool crosslinguistically for populations with language impairments (e.g. children with SLI). Apart from their use in monolingual speakers, recently, EITs have been administered in bilingual speakers (Chondrogianni et al., 2013).

Studies with bilingual children have shown that the age of onset to the L2 and the length of exposure to the L2 seem to play a crucial role in the performance of bilingual speakers (Chiat et al., 2013). In a study by Chondrogianni et al. (submitted) sequential bilingual children have been found to score lower than monolingual and simultaneous bilingual children on an EIT. However, the results revealed that there were no differences in morphological and structural errors among the three groups; rather, the sequential bilinguals made primarily lexical errors and this was confirmed by the fact that their performance on EIT was predicted by their lexical abilities and their age of onset to the L2. The result indicates that the role of lexical knowledge is important for the accurate performance on task. Additionally, EITs are complex linguistic tasks that depict language processing systems at many different levels, such as speech perception, lexical (vocabulary) knowledge, grammatical skills and speech production (Klem et al., 2015). Studies on L2 have pointed out that apart from processing, EITs exhibit language representations and indicate general language proficiency (Chaudron and Russell, 1990; Munnich et al., 1994).

There is a long discussion about the involvement of working memory abilities in EITs. Some studies note that either verbal short term or working memory are highly involved (Alloway and Gathercole, 2005; Alloway et al., 2004). Quite limited studies suggest that memory is more involved compared to language in those tasks (Hamayan, Saegert, and Larudee, 1977). Other studies have not found the contribution of memory in participants’ performance (Okura and Lonsdale 2012, Dosi et al., 2016). Nonetheless, in the study of Dosi et al. (2016) other cognitive skills (i.e. updating) seems to predict participants’ performance on EITs, which according to previous studies, updating involves complex working memory processes. There is a great number of recent studies which suggest that EITs require both linguistic and cognitive abilities (Riches, 2012; Klem et al., 2015).

Research questions and hypotheses

From the aforementioned presented studies our research questions are the following: (a) does language proficiency have an impact on participants’ performance and (b) do EITs measure both linguistic and (verbal) working memory abilities. Our hypotheses are that language proficiency will have an impact on participants’ performance and EITs will measure both linguistic and working memory skills.

The present study aims to test both linguistic and verbal working memory skills in L2 learners of English with Greek as L1. Different proficiency levels were also taken into account.

Participants

The participants of the present study were all adults with relatively high level of proficiency in the target language (English). Eight adult learners participated in the study; half of them (n = 4) were intermediate L2 learners of English (CEFR B2) and the other half (n = 4) were advanced L2 learners of English (CEFR C2). We should note that the participants did not take a proficiency test; they were selected based on the level of the language diplomas that they hold and the suggestion of their instructor. The participants were recruited by New York College of Thessaloniki, where they attended business classes. The age range of the participants was 20-30 years old with the mean age being at 22.5 years. Most of them were men (n=5) and the women were three (n=3). The overall years each participant had been learning English were considered as an important factor; the majority of the participants were learning English for an average of seven years.

Materials and procedure

Two offline tasks were administered to the participants; an EIT and a cognitive task, which tested the verbal working memory. Their answers were recorded and analyzed later on.

Elicited imitation tasks

The first task administered to the participants was a Sentence Repetition Task developed within the COST Action IS0804 ‘Language Impairment in a Multilingual Society: Linguistic Patterns and the Road to Assessment’ (Marinis and Armon- Lotem, 2015). Marinis (2015) designed this task in three different stages, varying in complexity of the grammatical structures used in the sentences, moving from the simplest to the most complex stage (Marinis and Armon-Lotem, 2015). The sentences tested negation, subordinate and coordinate structures (main clauses, adverbial clauses, relative clauses, a.o.). The task consisted of 32 sentences. The word mean per sentence was 8.68. The sentences were audio-tapped and the task was presented in a Power Point version.

Procedure

Each participant was tested individually in a quiet room. In order to familiarize the participant with the task, three practice sentences were administered and the participant had to recall the sentences as accurately as possible. During practice sessions, participants were given feedback for both accurate and inaccurate answers. The whole procedure was audio recorded.

Scoring

The task was assessed with respect to two factors, (a) grammaticality and (b) accuracy. The grammaticality scores referred to whether the utterance of the participant was grammatical or not. Thus, if the utterance produced by the participant was grammatical, (s)he received 1 point, while, if the utterance was ungrammatical, the participant received no points. Accuracy scores pertained to how accurately the participant repeated the sentence. If the participant’s utterance exactly matched the sentence given, the participant received 3 points, whereas, if the participant made any lexical or grammatical substitution, omission or addition, they received 2 points. Moreover, if the participants made two of the aforementioned errors, they received 1 point and, if the participant made three or more errors, they received no point. The maximum accuracy score is 96 (32x3).

Verbal working memory task

The backwards digit recall task is a computerized measure of verbal working memory from the Automated Working Memory Assessment (AWMA, Alloway, 2007). In this test the child is required to recall a sequence of spoken digits in reverse order. Digit sequences were audiotaped with the distance between the offset of a digit and the onset of the next one to be 1 second. Test reliability of the AWMA is reported in Alloway (2007) and test validity in Alloway et al., 2009). This is a span task in which the number of digits to remember increases progressively over successive blocks containing 6 trials each. The criterion for moving on to the next block was the correct recall of 4 out of the 6 trials. Testing stopped if the child failed in 3 trials in one block. The task consisted of 6 blocks, starting with 2-digit sequences in the first block and increasing to 7-digit sequences in the last block.

Procedure

Each participant was tested individually in a quiet room. In order to familiarize the participant with the task, three practice trials were administered in which the participant had to recall 2- and 3-digit sequences. During practice session, participants were given feedback for both accurate and inaccurate digit recalls. The examiner entered the scores in an evaluation grid.

Scoring

Each correct answer was given 1 point and there were no penalty points for wrong recalls. The first 4 consecutive successful recalls in each block were scored as 6 points; the participant then moved to the next block. If the fourth correct recall was on the fifth or the sixth trial, the participant got in total 5 and 4 points, respectively. The same scoring procedure was repeated across all 6 blocks. The highest possible score was 36 points.

The results of this study will be presented in two different sections; the first section includes the results of the EIT, whereas the second section presents participants’ performance on the verbal working memory task. Since there is a small scale study, we run non parametric test on the SPSS Statistical Analysis Program 21.

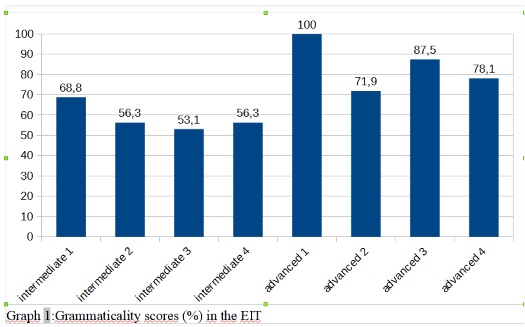

In the EIT, the grammaticality scores depict that the overall scores of the intermediate group is lower than the advanced group (58.6% and 84.4%, respectively; U(8)=.000, z=-2.323, p=.029). The result indicates that the group with the higher proficiency has the innate knowledge of producing grammatical sentences compared to the intermediate group, in which the sense of grammaticality in English is not so strong. Interestingly, in the advanced group there was a participant, who performed native-like (see Graph 1).

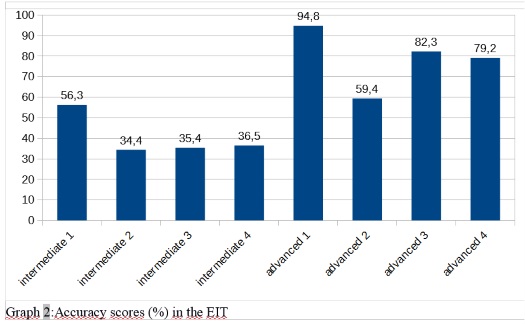

The results in the accuracy scores show that advanced group scored higher than the intermediate one (79% and 40.7%, respectively; U(8)=.000, z=-2.309, p=.029). In the intermediate group three out of four participants scored quite low (see Graph 2).

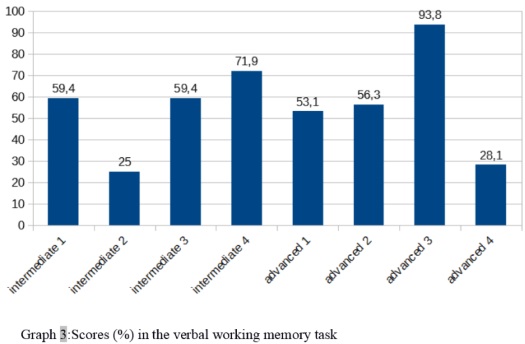

Our results in the verbal working memory task indicate that the intermediate group scored in total 54%, whereas the advanced group scored 57,8%. The two groups did not differ in terms of their performance on the task (U(8)= 7.000, z= -.290, p=.886). Interestingly, two participants scored quite low (25% and 28.1%) and one participant from the advanced group scored almost at ceiling (see Graph 3). Therefore, there are high standard deviations within the groups.

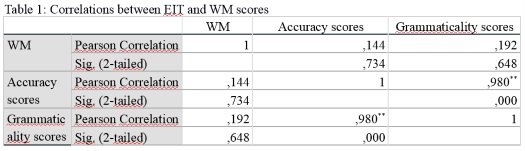

In order to answer to our second research question, we run Pearson’s correlations. We assume that if accuracy scores correlate with working memory scores that will be an indicator of the involvement of working memory in the EIT performance. We do not expect the grammaticality scores to correlate with the working memory (WM) scores, since sense grammaticality is not related to the memory capacity.

From our results the aforementioned hypotheses are not fully confirmed. Working memory scores do not seem to correlate neither with accuracy nor with grammaticality scores (r=.144, p=.734; r=.192, p=.648, respectively). Not surprisingly, accuracy scores seem to highly correlated with the grammaticality scores.

The present study focuses on whether EITs measure linguistic and/or working memory abilities. Our results showed that advanced L2 learners outperformed the intermediate ones in both grammatical and accuracy scores. In the advanced group, there was a participant who scored native-like. No differences were detected in the verbal working memory task. This outcome supports the claims of previous studies, that EITs are primarily methods of assessing learners’ linguistic competence (DeKeyser, 2003; Erlam, 2006). Based on this, participants seemed to focus on the meaning of the stimulus in order to more easily repeat it (DeKeyser, 2003). Lexical chunking was not examined in this study, but it is still possible that at least some of the participants used it as a mechanism to group the new information and perform better (Cowan, 2001).

Answering to our first research question, the level of proficiency played a significantly more important role in the participants’ performance in the linguistic task (Bley-Vroman and Chaudron, 1994; Munnich, Flynn and Martohardjono, 1994), but not in the working memory one, as expected. Answering to our second question, from the correlations between working memory and linguistic skills, the two skills do not seem to correlate with each other (contrary to previous studies, Riches, 2012; Klem et al., 2015). The results indicates that EITs measure more linguistic, rather than memory skills (Okura and Lonsdale 2012, Dosi et al., 2016). However, at this point we should note that the sentences used in the present study had the same length. Possibly, the results may differ if the sentences were shorter (Jessop, Suzuki and Tomita, 2007; Okura, 2011). In addition, we should bear in mind that there was a small number of participants, who took part in the study. It is likely that the result may be different if the sample was greater.

Another interesting finding is that the grammatical scores correlate with accuracy scores. The finding exhibits that the sense of grammaticality is related to how accurate the participant will repeat the answer (similar to other studies, Andreou, Dosi, Papadopoulou and Tsimpli, in press).

In a nutshell, the hypotheses of this study seem to be partially verified. More specifically, the participants of advanced level in English performed higher than the participants of intermediate level in the EIT. From the above we may deduce that EITs can be used as valid testing method of language skills and more specifically of language proficiency. Finally, the EITs do not seem to rely on working memory skills; therefore, from our results, EITs are better measurements of linguistic rather than memory skills. The present study suggests EITs as a useful tool and indicator of second language proficiency.

ANDREOU M., DOSI, I., PAPADOPOULOU, D. and TSIMPLI, I. M. (in press). Heritage and Non-heritage Bilinguals: the Role of Biliteracy and Bilingual Education. In Studies in Bilingualism. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

ALLOWAY, T. and GATHERCOLE, S. (2005). Working memory and short-term sentence recall in young children. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 17(2), pp.207-220.

ALLOWAY, T., GATHERCOLE, S., WILLIS, C. and ADAMS, A. (2004). A structural analysis of working memory and related cognitive skills in young children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 87(2), pp.85-106.

BLEY-VROMAN, R. and CHAUDRON, C. (2013). Elicited Imitation as a Measure of Second-Language Competence. In: E. Tarone, S. Gass and A. Cohen, ed., Research Methodology in Second-Language Acquisition, 1st ed. Routledge.

CHAUDRON, C., & RUSSELL, G. (1990). The status of elicited imitation as a measure of second language competence. Paper presented at the Ninth World Congress of AppliedLinguistics, Thessaloniki, Greece.

CHIAT, S., ARMON-LOTEM, S., MARINIS, T., POLISENSKA, K., ROY, P., & SEEFF-GABRIEL, B. (2013). The potential of sentence imitation tasks for assessment of language abilities in sequential bilingual children. In V. C. M. Gathercole (ed.), Bilinguals and assessment: State of the art guide to issues and solutions from around the world. Multilingual Matters.

CHONDROGIANNI, V., ANDREOU, M., & TSIMPLI, I. M. (submitted). Predictors of monolingual and bilingual Greek-speaking children’s performance on sentence repetition. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders.

CHONDROGIANNI, V., ANDREOU, M., NERANTZINI, M., VARLOKOSTA, S., &TSIMPLI, I. M. (2013). The Greek Sentence Repetition Task. COST Action IS0804.

DOSI, I., PAPADOPOULOU, D. and TSIMPLI, I. (2016). Linguistic and Cognitive Factors in Elicited Imitation Tasks: A Study with Mono- and Biliterate Greek-Albanian Bilingual Children. In: Proceedings of the 40th annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp.101-115.

ELLIS, N. C. (2005). At the interface: Dynamic interactions of explicit and implicit language knowledge. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 27, pp. 305-352.

ERLAM, R. M. (2006). Elicited imitation as a measure of L2 implicit knowledge: An empirical validation study. Applied Linguistics,27(3), pp. 464-491.

FATTAL, I., FRIEDMANN, N., & FATTAL-VALEVSKI, A. (2011). The crucial role of thiamine in the development of syntax and lexical retrieval: A study of infantile thiamine deficiency. Brain,134(6), pp. 1720-1739.

HAMAYAN, E., SAEGERT, J. and LARUDEE, P. (1977). Elicited Imitation in Second Language

Learners. Language and Speech, 20(1).

JESSOP, L., SUZUKI, W. and TOMITA, Y. (2007). Elicited Imitation in Second Language Acquisition Research. Canadian Modern Language Review, 64(1), pp.215-238.

KLEM, M., MELBY‐LERVåG, M., HAGTVET, B., LYSTER, S. A. H., GUSTAFSSON, J. E., & HULME, C. (2015). Sentence repetition is a measure of children's language skills rather than working memory limitations. DevelopmentalScience, 18(1), pp. 146-154.

MARINIS, T., & ARMON-LOTEM, S. (2015). Sentence repetition. In S. Armon-Lotem, J. de Jong & N. Meir (eds.). Methods for assessing multilingual children: Disentangling bilingualism from Language Impairment.Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

MOZGALINA, A. (2015). Applying an Argument-based Approach for Validating Language Proficiency Assessments in Second Language Acquisition Research: The Elicited Imitation Test for Russian. Ph.D. Georgetown University.

MUNNICH, E., FLYNN, S., & MARTHOHARDJONO, G. (1994). Elicited imitation and grammaticality judgment tasks: What they measure and how they relate to each other. ΙnResearch Methodology in Second-language Acquisition, E. Tarone, S. Gass& A. Cohen (eds.), 227-45. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

OKURA, E. (2011). A Study of the Correlation Between Working Memory and Second Language EI Test Scores. Master. Brigham Young University.

OKURA, E. and LONSDALE, D. (2012). Working memory’s meager involvement in sentence

repetition tests. In: Proceedings of the 34th Annual Conference of the Cognitive

Science Society. Austin: Cognitive Science Society, pp.2132-37.

RICHES, N. G. (2012). Sentence repetition in children with specific language impairment: an investigation of underlying mechanisms. International Journal of Language &Communication Disorders, 47(5), pp. 499-510.

SLOBIN, D. and WELSH, C. (1968). Elicited imitation as a research tool in developmental psycholinguistics. 1st ed. Berkeley: Language-Behavior Research Laboratory, University of California.

VINTHER, T. (2002). Elicited imitation: a brief overview. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 12(1), pp.54-73.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English Update for Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English Language course at Pilgrims website.

|