Multimodal Processing and Cognitive Load: Exploring EFL Learners’ Perceptions on the Effect of Bimodal Subtitling on Listening Comprehension

Foteini Malkogeorgou and Vasiliki Papadopoulou, Greece

Foteini Malkogeorgou is a lecturer of Methodology of Second Language teaching and material design, levels 5 & 6 at the BA (Hons) English and English Language teaching programme of the University of Greenwich which is offered at New York College. She is the academic manager of the ELT department of New York College Thessaloniki.

Vasiliki Pappadopoulou is an EFL teacher working at Anatolia. She is a graduate of the BA (Hons) English and English Language teaching programmeof the University of Greenwich offered at New York College. She is interested in second language acquisition and teaching.

Menu

Introduction

Background

Research questions and hypotheses

The present study

Results

Summary and discussion

References

Our interaction with our environment, artifacts and humans, is by nature multimodal. We sense the world using all our senses sight, hearing, touch, and smell. Humans can use their senses either simultaneously or parallel, to process the external stimuli. Advances in technology have provided opportunities with the design of digital multimedia for combining sound, text, and image and enhancing language acquisition. Multimodality also exists in traditional media such as film. Films involve the moving/dynamic picture (image) and speech (audio). Films, documentaries and other similar authentic media are used in the foreign language classroom to enrich the input offered to learners and facilitate second language acquisition and development. It is common practice to make available to the learners subtitles in the language of the audio (bimodal subtitles) with the assumption that listening, reading and following the moving picture at the same time may facilitate comprehension and develop their listening comprehension skills.

By adding a third modality however, the textual (subtitles) it is not given that it will enhance or facilitate processing, nor that the learner will be processing all modalities simultaneously as thetask of processing three modalities audio and text, which carry the same identical information, and a rich moving picture is complex and demanding and may createcognitive load effects because the processing requirements of the task could be ‘outpacing the processing capacity of the cognitive system’ (Mayer and Moreno 2003: 45). The cognitive load theory (CLT) developed by Sweller et al. (1999) is related to the make-up and limitations of the working memory. It is concerned with how learning can be facilitated and how the cognitive load effects can be reduced.

The present small scale study aims to explore learners’ perceptions on whether viewing the moving picture and simultaneously reading subtitles in a foreign language and listening to the same information in the target language creates cognitive load and how they deal with this demanding task in order to assist their comprehension.

Multimodal processing and working memory

Films offer a complex context, the spoken language and the rich in cues dynamic image. When this is subtitled then the viewers are also exposed to a third modality the textual which they are required to process at the same time. This is what Meskill (1996:182) refers to as a ‘multi modal processing’. It has been claimed by studies that when attempting to process information from multiple modes simultaneously a cognitive load exists. The cognitive load theory (CLT) is based on the limited capacity of the working memory (Miller, 1956; Baddley, 1986). The working memory is responsible for storing temporarily and processing information which is necessary in order to execute complex cognitive tasks (Baddeley, 2003). Baddeley’s (2010) working memory model assumes a multi-component memory that consists of three systems which have limited capacity of processing and storing information, the central executive and the two slave/subsidiary systems the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketchpad. The phonological loop stores speech-based information possibly purely acoustic, while the visuospatial sketchpad stores visual and spatial information. According to Mayer’s (2001) generative theory, understanding what a text means is facilitated when it is accompanied with pictures due to the extra explanation the picture provides but if spoken text (audio) is accompanied with pictures and written text as well, then this may create a processing problem. Mayer’s (2001) cognitive theory of multimedia learning posits that the human knowledge processing system contains two different processing channels one for visual/pictorial and one for the auditory/verbal (dual-channels assumption), each channel has a certain capacity for processing and active learning involvestransmitting a coordinated set of cognitive processes. This is in line with Paivios’ (1986) dual coding theory which identifies two distinct subsystems, the verbal system and a nonverbal system. The verbal system processes linguistic input, while the non-verbal is occupied with non-linguistic input such as images, these are processed separately but are connected.Baddeley’s (1986) working memory model sees these two processes as coordinated by a central executive which coordinates the two subsystems the visuospatial sketchpad and the phonological loop (Baddeley, 1986; Baddeley &Logie, 1999).

Another effect that results from exposure to the three modalities; audio, textual, and image, as in the case of films with bimodal subtitling, is that of the split-attention effect. The cognitive load theory (CLT) suggests that when learners have to split their attention between text and visual information which they try to mentally accommodate and assimilate, they may overwhelm the limited capacity of the working memory and thus learning may be constrained. When text is accompanied with pictures and speech this automatically is directed to the visual channel, while when the text and the audio carry identical meaning this may cause the redundancy effect (Toh, Munassar&Yahaya, 2010) as in the case of films with bimodal subtitles.

Implications for learning

While multiple media can provide authentic input and facilitate listening comprehension, at the same time it is significantly cognitively demanding because of the cognitive load challenge (Mayers and Moreno, 2003). Meaningful learning requires that the learners are substantially involved in processing cognitively throughout learning and that cognitive load is reduced. Thus while learning is facilitated with exposure to two modalities, pictures and aural information, it may be hampered when pictures are presented with written text because of the split of visual attention which takes place as the eye switches from picture to text and when the time available is limited, this split has even further negative effects on learning.

For this reason, it can be assumed that when the learning objective is to develop listening comprehension skills, this may be supported if the film is presented without subtitles otherwise the task becomes complex and it depends on individual differences how it will be managed by the learners. Lavaur and Bairstow (2011:455) tested the effect of subtitles on film comprehension on native French speakers of different levels of English (beginner, intermediate, and advanced). The results suggestthat the simultaneous presentation of the three types of information interfered with each other as both the aural dialogue and the subtitles carried the same meaning. Thus the beginners attained information from visual aspects rather than dialogue while for the intermediate participants the subtitles were more effective and for the advanced even though they scored the highest in comprehension, subtitles had a disturbing effect on them.Baltova (1999) conducted a study where she actually attempted to measure if subtitles assist listening comprehension, the results indicated that while L2 subtitles (Bimodal video) facilitated retention of vocabulary and content the written information, instead of being a support for the aural information, it was the main source for comprehension. In other words, the subjects (93 Canadian lower-intermediate learners of French) did reading comprehension rather than listening. Rokni and Ataee (2014) aimed through their experiment to analyzing the effect of subtitles through watching English movies on the speaking ability of students of 38 intermediate Iranian learners of English EFL. There were two groups the experimental and the control. Both groups observed the same English movie the experimental group watched it with the use of subtitles, while the control group watched it without the use of subtitles. After the study, students were required to take the speaking posttest. The results displayed a development considering speaking ability of the experimental group.

Brett (1997:39) measured listening comprehension performance of EFL learners in a computer-based multimedia environment which combined the three media and the traditional subtitled video. The computer-based environment scored higher and that is because the software design allowed learners to control their viewing and select what media they prefred and could control their viewing as well. These circumstances do not apply in the case of viewing a conventional video with subtitles. According to Diaz-Cintas and Remarl (2007), the reading of subtitles is demanding because the speed of reading is not controlled by the learner and because the position of the subtitles which is at the bottom of the screen may cause the viewer to miss what is happening on the screen and vice versa. They also posit that intralingua subtitles on the other hand, may facilitate language learning.Toh et al (2010) also gave control to the subjects of his study. They carried out a study to test whether visual verbal redundancy creates a cognitive load and affects learning for EFL learners. They examined the effects of multi modal redundancy on EFL learners. There were two groups, the redundancy group which consisted of 98 Yemen Learners college students and 111 college students in the modality group. The learners of the two groups were offered the choice to pace their viewing. The redundancy group was provided with static pictures, audio narration and on-screen text which was very well synchronized. The modality group was presented with the static picture and the audio narration only. The results showed that the redundancy group performed better and this was attributed to the fact that the learners had control over the pace of the multimedia material and the redundant synchronized text facilitated their understanding of the audio text. As Toh et al (2010) suggest, the cognitive load and split attention were minimized as the text was presented in the picture next to the referring part. They also posit that for learners of English as a foreign language understanding narration in the target langauge is cognitively demanding while the simultaneous presentation of the redundant text in the picture at the correct level reduces cognitive load. However, it was the instructional design that reduced the redundancy effect, the split attention effect, and the cognitive load through the synchronized presentation of small chunks and learner control. These conditions do not apply in the case of viewing films with bimodal subtitling.

Based on the literature and research presented the research questions explored in this small scale survey are:

- Do learners find watching an English documentary with bimodal subtitles a demanding task?

- Which media do they rely on to assist their comprehension and which do they consider unnecessary?

The participants of the study were 8 undergraduate studentsaged from 18 to 22 who study Business administration. The participants were chosen based on their results of a TOEFL test. This was done to ensure homogeneity in terms of their language level. The participants were B1 (CEFR) level. All students had Greek as their L1 and were attending an English language support course to improve their English. Two excerpts of the BBC Documentary “Wild Weather” were used. The excerpts used dealt with completely different aspects of weather conditions to ensure that the schemata built from viewing the first excerpt will not help in the comprehension of the second. The two sections together comprisedaltogether a 14 minute video. Excerpt A was viewed with bimodal subtitleswhile excerpt B was viewed without subtitles.A comprehension testwith 5 Yes/No questions and 3 multiple choice questions for each section of the documentary was designed to measure comprehension and a questionnaire was designed to explore perceptions and preferences (McDonough & McDonough, 1997). Questionnaires have been introduced by Paas, van Merriënboer and Adam(1994) to measure indirectly and subjectively learner perception of the mental effort required for a task. It is questionable whether mental effort indicate cognitive load but the answers do offer useful information to be considered for learning purposes. The questionnaire included 11 questions which explored their personal experience of observing the two excerpts but also comparing viewing with and without subtitles and choosing which media they consider as unnecessary to comprehend the excerpts. The type of questions included, Yes/No questions for quick factual information, multiple option answer questions to provide participants the option to select multiple answers and and avoid forcing them to choose one of the available options, the option ‘other’ was provided (McDonough & McDonough, 1997),like scale rating questions, specifically a 3 scale rating to save from possibly confusing the participants with more options (Jacoby &Matell1971: 496) and open – ended follow up questions which allow the respondents to express their views (Nunan, 1992) and may indicate more clearly what the respondents want to say and generate qualitative data, which is important when the aim is to understand attitudes and behavior (Guba & Lincoln, 1994)

Procedure

The experiment took place at New York College in Thessaloniki in a classroom with a big screen and loud speakers. The comprehension questions were first handed out to the participants. After the students had read the questions for the first excerpt, the handouts were taken away to ensure that they would not be distracted by trying to answer questions while watching the documentary, something that would have caused an extra load. The comprehension questions gave some kind of a purpose for watching and activated schemata. The participants watched excerpt A with the subtitles and afterwards they were given the handouts to answer the comprehension questions. The same procedure was followed for the second excerpt too. Finally, the participants were handed the questionnaire and were asked to complete it.

Data Management

Considering that the sample was small (n=8) the data generated were managed manually. Excel was used to draw bar charts to illustrate frequencies and pie charts to depict proportions and interpretations of the results are given in summaries. The qualitative data generated from the open-ended questions were organized in tables to find recurring answers and locate emerging issues, which are presented also in summaries (Opie, 2004).

The results show that higher comprehension was achieved for the subtitled excerpt as 45% of the participants achieved the highest score 80% correct answers, while for the excerpt which was not subtitled the same percentage was achieved by 25% of the participants. It seems that the subtitles assisted most of the students in understanding the excerpts. However, the question is how this was achieved.

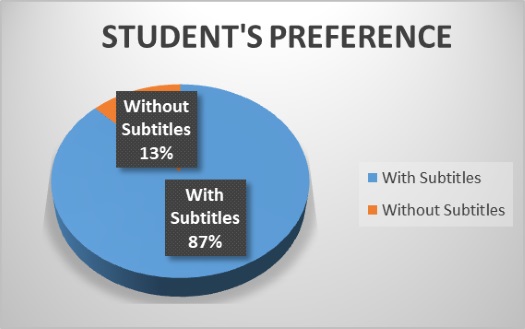

The results from the questionnaire which was completed by the students after watching both of the excerpts presented a significant preference for subtitles at 87% as illustrated in figure 1. Overall, the answers showed that the respondents who preferred the subtitled excerpt expressed their weakness in understanding spoken English and felt more confident with reading.

Figure 1

Only 13% of the students (figure 1) preferred watching the documentary without subtitles as they found the aural input easy to understand. These respondents seemed to have confidence in their listening skills.

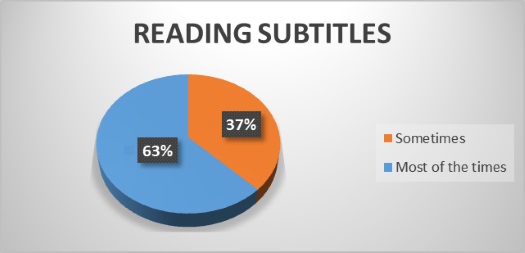

Regarding the question ‘how often they read the subtitles’, as shown in figure 2, 37% of the students answered ‘sometimes’ while the other 63% ‘Most of the times’, none of the students actually ignored them completely.

Figure 2

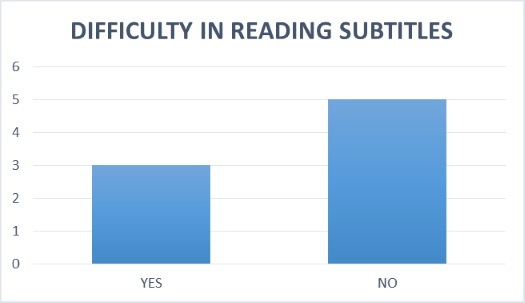

As illustrated in figure 3, just over half of the students did not find any difficulty in reading the subtitles, while 3 admitted that it was a difficult task and the difficulty was attributed by the participants to the ‘unknown words’ and the ‘difficulty in reading and watching at the same time’

Figure 3

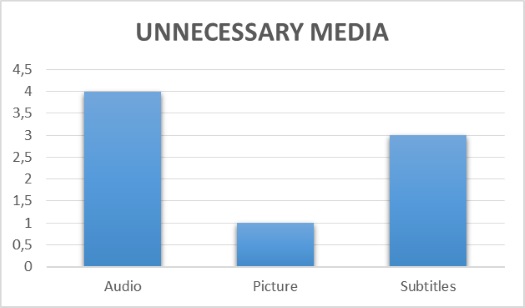

Finally, the participants were asked to decide which media they could do without if they were given the opportunity to take out one: audio, picture, or subtitles. As figure 4 illustrates, half of the respondents would opt to take out the audio while 3 respondents would choose to do without the subtitles and leaving 1 student that would choose to remove the picture.

Figure 4

The participants who preferred to remove the audio felt that reading subtitles helped them more as opposed to listening to the audio.

The findings of the present study show that intermediate students preferred the excerpt with subtitles, instead of the one without. It is clear that for the subtitled excerpt comprehension scores were higher and it appears that this was achieved through reading and viewing rather than listening and viewing. The data from the questionnaire indicated that a difficulty was created by the task of watching the video and reading the subtitles simoultaneously. On the other hand, when the participants were asked to take out one of the media most of them opted to exclude the audio, since they found it unnecessary for comprehension. It appears that those with poor listening skills relied more on their reading the text to comprehend the excerpts than on the spoken information. This is in line with Lavaur and Bairstow (2011) who suggest that viewers may tend to read more than listen if they do not comprehend the spoken language and Brett’s (1997) assertion that ‘reading text on screen seems to require relatively low effort’. Thus, the majority of the participants instead of doing a listening comprehension task did a reading comprehension task. Thus participants were selective as to choosing to process what they found most helpful in order to achieve the task.

As Perego et al (2010:243) found in an eye tracking experiment; ‘participants seem to deploy efficient and selective attention allocation strategies which enable them to reach a good understanding and a good recognition of presented information’. In the current study it seems that the majority of the participants did not process all three modalities and opted for reading in order to achieve the task.Therefore, when learners view a film with bimodal subtitles it is not given that they are practicing their listening comprehension skills or assisting these skills with the reading text. On the contrary, it is more likely that they are actually doing a reading comprehension task.

Baddeley, A. (2003). Working memory and language: an overview. Journal of Communication Disorders, 36(3), pp.189-208.

Baddeley, A. (2010). Working memory, thought, and action. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Baltova, I., 1999. Multisensory Language Teaching in a Multidimensional Curriculum:

The Use of Authentic Bimodal Video in Core French. Canadian Modern Language

Review 56 (1), 32-48.

Horz, H. and Schnotz, W. (2008). Multimedia: How to Combine Language and Visuals. Language at Work - Bridging Theory and Practice, 3(4).

Mayer, R. E., Heiser, J., &Lonn, S. (2001). Cognitive constraints on multimedia

learning: When presenting more material results in less understanding.

Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 187–198

Mayer, E.R. and Moreno, R. (2003).Nine Ways to Reduce Cognitive Load in Multimedia Learning, EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGIST, 38(1), 43-52

McDonough, J. & McDonough, S. (1997). Research Methods for English Language Teachers. London: Arnold

Meskill, C. (1996). Listening Skills Development Through Multimedia, JI. of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 5(2), 179-201

Nunan, D. (1992). Research Methods in Language Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Opie, C. (2004). Presenting data. In Opie, C. Doing educational research: a guide to first-time researchers. London: Sage, 130-161.

Paivio, A. (1986). Mental representations: A dual coding approach. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press

Paas, F. G. W. C., & van Merriënboer, J. J. G. (1993). The efficiency of instructional

conditions: An approach to combine mental-effort and performance

measures. Human Factors, 35, 737–743.

Rokni, A. J. S. and Ataee, J. A. (2014). The Effect of Movie Subtitles on EFL Learners’ Oral Performance, International Journal of English Language, Literature and Humanities, 1 (5), 201-215

Toh,S. C., Munasser,S.A.W and Yahaya, W.J.A.W(2010).Redundancy effect in multimedia learning: A closer look.Ascilite Conference Proceedings, Sydney. Available athttp://ascilite.org.au/conferences/sydney10/As... [Accessed: January 2015]

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Practical uses of Technology in the English Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

|