Ten Secrets of Effective Language Teaching

Luke Prodromou, Greece

Dr Luke Prodromou graduated from Bristol University in English with Greek and has an MA in Shakespeare Studies from Birmingham University; a Diploma in Teaching English as a Second Language (Leeds University, with distinction) and a Ph.D (Nottingham University), published as English as a Lingua Franca: a Corpus-based analysis (Continuum, 2010). He is also the co-author of numerous coursebooks (most recently: Smash, Flash on, Sprint), the award-winning Dealing with Difficulties (with Lindsay Clandfield) and Grammar and Vocabulary for Cambridge First (Longman). Luke is a founder member of the Disabled Access Friendly Campaign for which he wrote the ‘Wheelchair Sketch’. He has been a plenary speaker at numerous international ELT conferences, including IATEFL, UK. He was for many years a teacher and teacher-trainer with the British Council. He has also worked for ESADE, Barcelona, the University of Edinburgh, the University of Thessaloniki, Pilgrims Canterbury, NILE, Bell Schools et al. He currently teaches ELT Methodology, part-time, on the MA TESOL University of Sheffield International Faculty, City College, Thessaloniki. He also performs with the English Language Theatre/Luke-and-Friends.

Menu

Miss Cooper's Secrets

The secret of presence

Observation

Methodological correctness

A ten-year-old's advice to teachers

My favourite teacher surveys

Metaphors we learn by

Back to school

My dance diary

Empirical research

Conclusion: The deep structure of good teaching

References and further reading

Miss Cooper, my very first primary school teacher, was a teacher with an attitude – or, more precisely, with a parrot.

My first memory of Miss Cooper is when we all sat round listening to her reading fairy-tales: she usually chose her stories from the treasure trove provided by Hans Christian Andersen and the Greek myths. How did her storytelling work its magic? It began with ‘once upon a time’ and these words would open up new worlds of witches, princes and giants; dogs with eyes as big as saucers, gods who kept changing shape and an endless battle between good and evil. So much for the content of Miss Cooper’s stories. But what of her manner, her style of storytelling? Her voice compelled her overactive little charges to listen:...I may now be able to explain her use of volume but at the time I knew only a vague sense of pleasure in listening to her telling tales about heroes, gods and battles long ago.

One specific technique she always used and which never failed to motivate us to want more of her stories was the ‘cliffhanger’: Miss Cooper would stop at an exciting moment in the story, close her book and say: ‘We’ll continue with the story next Friday’. I particularly remember her applying this cliffhanger technique to the story of Orpheus and Eurydice: she paused for a whole long week just as Orpheus, with his lyre, was leading Eurydice out of the underworld; the young man was forbidden to turn round to look at his love; if he did, he would lose her to Hades forever. The suspense was killing; our attention next time was complete.

The second thing I remember about Miss Cooper, is the day she taught me to swim. In those golden days of the Welfare State, they used to take us to the swimming baths every Wednesday in order to teach us how to swim. The day came for me to swim a length: from one end of the pool to the other. As I splashed my way, yard by yard, from one end of the pool to the other, swallowing gulps of water, I felt I was drowning. Throughout this embarrassing ordeal, in full view of my infant peers, Miss Cooper walked along the edge of the swimming pool, bending over and saying loudly enough for me to hear her through the gurgling water in my ears: ‘you can do it, Luke, you can do it’...and I did it! Much wetter – both of us – but much happier.

So Miss Cooper’s second secret as a great teacher was encouraging pupils and enabling them to succeed.

And Miss Cooper’s third secret? I suppose today we would call it ‘classroom management’ or ‘dealing with discipline’. I was a naughty 6-year old. I did bad things like wetting myself or - even worse - pouring sand from the sandpit down the back of the little girl sitting next to me. I got told off, but that’s not what sticks in my mind. I remember Miss Cooper asking me to come to the front of the class and go to a table on which there was a parrot in a cage. Miss Cooper’s pet had red, blue and yellow feathers. My ‘punishment’ for misbehaving was to speak to Peter the Parrot. I loved it. Miss Cooper’s third secret was transforming bad behavior into a learning opportunity: instead of using threats, or conventional penalties, Miss Cooper deflected my energy and distracted my attention with something amusing and slightly magical. In the talking Parrot, there was humour and enchantment.

Yes, I still remember Miss Cooper, my first teacher.

A major landmark in my personal development was the discovery of theatre. I had started taking part in school plays from primary school days. I was an eight-year old Herod in the nativity play, slaughtering the innocents. Drama gave me the first insights into the connection between communication and the use of voice, body language and space, but also its role in creating the elusive quality of ‘presence’ – that strange ability to get yourself noticed, to engage people’s attention. Drama skills, on the interpersonal and intrapersonal level, helped one to find one’s inner voice or ‘presence’, the ability to be present in the moment and to make others be present and to listen attentively. But how is presence constructed?

On the interpersonal level, drama highlights the essential role of what we might call co-operative interaction. You can’t do drama on your own: even if you know how to use the big three (Voice, Body Language and Space) you can achieve nothing without working with others, in a spirit of collaboration. You have to listen and respond; it is through such interaction that the language takes shape; moreover, that mysterious but essential quality, presence, depends on this kind of interaction (Rodenburg, 2007). To be ‘present’ you have to focus, pay attention, and practise collaborative interaction. Research summed up in Borg (2006) confirms time and again the important role of responsive interaction in good language teaching.

Presence, so important to both actors and teachers, is not a solitary skill; it is, by definition, collective and interactive. This was a lesson I began to learn for the first time in the preparation and performance of school plays at primary and secondary school.

As I began my first formal study of teaching in order to acquire a professional qualification, apart from the list of academic papers we had to write, we also had to undergo teaching practice. This involved preparing a lesson and being observed by a tutor while teaching a real class and then receiving feedback on the lesson. Painful and nerve-wracking as the process was, it taught one to think about teaching, to notice aspects of one’s style as a teacher and to introduce changes to one’s practice. Observing each other at work is, I have found, one of the most effective means of teacher development.

One of the great privileges of my teaching career has been the opportunity my job has given me to observe other teachers in action in the classroom. Apart from the insights gained from watching a wide variety of teachers at work, it was fascinating to read the official examiners’ reports which summed up the main reasons why teachers pass and fail – or get distinctions. For example, the most successful candidates in one well known diploma course were, in a particular year, outstanding in the following ten areas:

| Subject area |

| 1 | Ability to establish rapport |

| 2 | Personality, presence, general style |

| 3 | Use of appropriate methods |

| 4 | General shape and balance of activities |

| 5 | Giving instructions |

| 6 | Use of aids and materials |

| 7 | Clarity of aims |

| 8 | Encouragement of learners |

| 9 | Voice: audibility, modulation |

| 10 | Patterns of interaction |

Table 1: qualities of successful teachers in teacher training scheme

It is interesting to see that the first two qualities of good teachers - in this scheme at least- had more to do with personal qualities than with technique, methodology or professional knowledge. The ability to build good relationships in class (‘build rapport’) and establish ‘presence’ are, it seems, defining characteristics of the good teacher in terms of acquiring this particular professional qualification.

As I report on the various ways in which I have acquired impressions of the good teacher over the years, it will be interesting to see if certain qualities and behaviours, such as encouraging learners, building rapport and voice, reappear again and again in different contexts and what this pattern may imply for teacher training and development.

But how do the requirements of teacher-training courses and formal qualifications such as the ones described in the previous section match what actually happens in classrooms? On most teacher-training courses it is conventional wisdom that a learner-centred communicative approach is a good thing. Many teachers will pay lip-service to such an approach and may even try to apply it, whether it is appropriate or not, on specific occasions; this is what we might call ‘methodological correctness’ - the unthinking application of prevailing notions of what is good and bad in teaching.

For example, in a methodologically correct approach, teachers are encouraged to apply a variety of interaction: whole class work, pair work and group work; a polite, friendly teacher who smiles is the default position; communicative games where students get up and mingle to complete a task are de rigueur. Teachers should not sit down throughout the lesson, they should get up and use the space; the focus on formal grammar is frowned upon, while teaching grammar to communicate is a good thing, and so on. Mainstream methodological correctness is made up of principles such as these and indeed, its basic features are no doubt generally good advice.

But teaching is not general: it always takes place in specific situations, with particular students, in real time. The needs of students unfold in concrete, complex ways and a good teacher is able not only to draw up appropriate lesson plans in the abstract, but to reflect critically on particular teaching situations and to interact with the class and its problems on the spur of the moment.

I will give an example of observing two teachers at work that made me question the conventional wisdom and to begin to see the qualities of good teaching as a complex matter with unpredictable elements interacting in subtle ways.

In table 2, I sum up what the two teachers, A and B, did.

| Teacher A | Teacher B |

| She sat throughout the lesson | She stood up |

| She was serious | She walked around |

| She focused on grammar | She smiled a lot |

| She corrected mistakes | She did pair work |

| She explained rules of grammar | She played games |

| She was polite | She was polite |

| She was friendly | She was friendly |

| She nominated | - |

| She was strict | She was lenient |

| She was reticent | She made amusing comments |

Table 2: the qualities of two teachers in action

The context was a secondary school in Europe. Teacher A, the co-ordinator of the English department at the school, was widely reputed to be a successful teacher. In this lesson, she was returning homework and giving individual students feedback on their errors. As she did so, she deviated from methodological correctness in a number of ways: she broke some of the guidelines - if not the ‘rules’ - of orthodox communicative approaches to language teaching: she focussed her lesson on grammar and, indeed, the formal aspects of grammar. She sat at her desk with a pile of corrected notebooks next to her and, naming each student, advised them on their work, giving simple, clear explanations of how the grammar worked. There were no jokes, no frills, just clear explanations conducted in a polite and friendly manner.

The second lesson, on the other hand, was meant to be ‘communicative’: the pupils were instructed to stand up and mingle; the aim was to exchange information with other people in the class, just as you might do at a party in the real world. For added authenticity, the teacher, always pleasant and friendly, put some music on. Naturally, the activity was noisy and the pupils, teenagers, were quite excited by the task. They spoke happily, mostly in their own language, ignoring the teacher’s repeated request to ‘speak in English, please, speak in English’. They were not following instructions and could not hear the teacher’s clarification of the instructions. The students were enjoying the task so much they were reluctant to sit down again; there were more polite appeals from the teacher to ‘please sit down’, hardly audible above the noise of the ‘party’. Eventually, in dribs and drabs, the students returned to their seats none the wiser about English or the purpose of the task. What had gone wrong? Was it poor instructions? Lack of appropriate support for the task or ‘scaffolding’? Was it the teacher’s personal qualities, her rather squeaky voice, lacking in authority?

The next section reports on a ten-year old pupil’s views on what good and bad teachers do. Although my young informant, my son Michael, was not present in either of the lessons I have described above, his words may begin to throw light on why the grammar lesson probably achieved more than the communicative lesson described in this section.

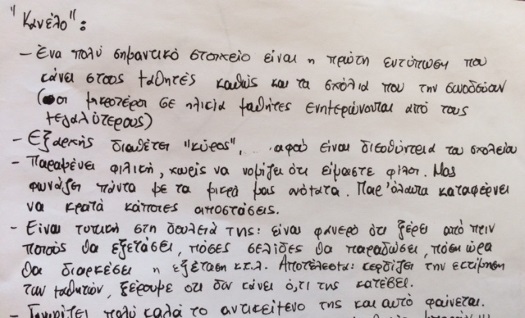

Here is what Michael, twelve years old, said about his good teacher:

Figure 1 A twelve-year old writes about his good teacher

- The first impression she makes on the pupils is very important.

- What people say about her, her reputation, is important. The young pupils hear about the teacher from older pupils.

- She has prestige – she is the head of the school.

- She is friendly without suggesting that we are friends.

- She always calls us by our first names. In spite of this, she keeps a certain distance.

- She is well organised. It is obvious that she has prepared the lesson and knows who she’s going to ask questions to, how many pages she’s going to cover, how long the checking is going to last. She earns pupils’ respect because they know she is not just making it up as she goes along.

- She knows her subject well.

|

What light do young Michael’s comments throw on the possible reasons why the grammar lesson was more successful than the communicative lesson in my brief case studies above? Both successful’ teachers, Michael’s and the one I had observed, Teacher A, had positions of authority in the school; although they used first names, they were friendly with pupils rather than being the pupils’ ‘friend’. Classroom Management was efficient, Michael’s teacher and Teacher A were well-organised and in control. Finally, they knew their subject well.

Teacher B’s behaviour can also be explained, to some extent, by what Michael says: the first impression was of a nervous teacher, she was too friendly, not well enough prepared, seemed to be improvising badly, and didn’t focus on particular students by name. In short, she seemed to be using inappropriate materials and methods for that particular class on that particular day.

BAD TEACHERS AS TESTERS

Michael, in another extract from his report, also had this to say about bad teachers in relation to testing practices:

- When we are taking a test, they say ‘you don’t have much time’ and they keep repeating it.

- They say the test is going to be difficult and that they are going to be very strict in their marking.

- They say that if we get bad marks our parents will ‘make us eat wood’ (punish us)

- Finally, when they give our tests back, they say we did terribly and they say mockingly ‘here are your howlers!’

It is interesting that this child’s view of the bad teacher has to do with the way the process of testing is handled: time constraints and marking are defining features of a test situation, as is the anxiety over the difficulty of the task and the embarrassment following poor performance. By implication, the qualities of good teaching should be the converse of these negative aspects of teaching. The defining features of testing as opposed to teaching do indeed come up in the same pupil’s description of the good teacher.

Michael, in the last part of his ‘report’ on teachers, makes the following comments about good teaching which may be considered the opposite of ‘testing’ approach to teaching:

- knows the students’ first name because this helps good relationships

- tells jokes to make the lesson more pleasant

- knows how to teach the essence of the subject

- asks what students already know about the subject before beginning the presentation

- should not use marks to terrorize pupils

- should ask questions to check understanding calmly and if the pupil gets stuck the teacher should ask something else...or to help the pupil

- should not discriminate between good and bad pupils but should treat them all equally

If we take these seven points in turn we see interesting links and contrasts between the concept of good teaching and the process of testing.

RAPPORT

Michael, identifies the importance of using pupils’ names in building good relationships in class. In exam-situations, of course, what matters is not the use of your first name but your candidate’s number; nobody cares what you like to call yourself as long as the name on the form and the index number match. In good teaching, we do care how the pupil likes to be called and we use this knowledge to create a sense of love, belonging and self-esteem (Maslow: 1954).

HUMOUR

Humour can be expressed in a number of simple ways, not necessarily through the telling of jokes, which is a skill some people have but others don’t.

Almond (2005) shares ways in which he uses humour in class that do not involve telling jokes:

- Making strange but encouraging noises to steer a learner towards the correct answer

- Wiping his brow and making a ‘phew’ sound when a student finally comes up with the correct answer.

- Blaming his pen when he makes a spelling mistake on the board

- Pretending to snore if a student is taking a long time to answer a question

- When drawing on the board, he points out that now the pupils can see why he became a language teacher and not an artist!

- Holding up two fingers if a student has made a mistake with the preposition ‘to’ (omission or intrusion) and four fingers if the mistake involves the preposition ‘for’.

Humour, of course, is conspicuous by its absence from the exam-situation. Testing is a serious, even solemn process; this solemnity is partly where it draws its authority from (Shohamy: 2001).

KNOWING THE SUBJECT

My young informant’s opinion that the teacher should know how to teach ‘the essence’ of the subject is a shrewd insight: being knowledgeable is not enough: one needs to be able to sift and select the most relevant aspects of the subject according to the needs of the class. Teachers must decide what to cover at any particular moment and to discard what may potentially confuse the students.

In examination situations, the texts are not chosen by criteria of relevance in terms of content but ‘testability ’in terms of level, length, and so on.

USING STUDENTS’ PREVIOUS KNOWEDGE

The pupil’s recommendation that good teachers draw on the learners’ background knowledge and build their presentation of the new topic on this knowledge is, according to serious empirical research (Borg: 2006), sound advice. Learners of English do not come cognitively naked into the classroom: they bring previous knowledge and experience on which their expectations are built; good teachers draw on ‘schema’ – the structure of preconceived ideas or frameworks for representing aspects of the world, which is helpful when perceiving, understanding and processing new information. My 10-year old anticipates the great cognitive educator, Piaget, in whose theory of development, children construct a series of schemata, based on the interactions they experience, to help them understand the world (Piaget: 1953)

TESTING v. TEACHING

My 12-year old son, Michael, once again puts his finger on a fundamental issue in successful English language teaching: the effect of testing models on the way we teach – the ‘washback effect’ (Alderson and Wall, 1993; Prodromou; 1995). Michael also identifies the role of motivation, intrinsic and extrinsic, in learning. The use of marks to inspire anxiety and even fear is a short-cut to ‘extrinsic motivation’ – it illustrates a carrot and stick approach to motivating learners and indeed is often adopted by parents to cajole their children into working harder so as to perform better in tests. My 10-year old disapproves of the strategy and like Dornyei (2001) recommends intrinsic motivation: getting learners to learn by making the subject interesting and relevant. Testing is all about extrinsic motivation, good teaching draws on both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

QUESTIONING AND ELICITING

An effective teacher needs to use language to present information clearly and to check understanding: these are general language skills but they are realized by the more specific sub-skills of asking questions, eliciting and prompting. The point young Michael is making is again one experts in pedagogy frequently make. Notice the use of the adverb ‘calmly’: ‘should ask questions to check understanding calmly…’; it’s not just the questions we ask but they way we ask them, the tone of voice we use. Not asking questions ‘calmly’ but in a threatening voice will raise levels of anxiety and may lead to failure to come up with the right answer. In all cases where a learner is struggling to reply the role of the good teacher says our 10-year old, is to reformulate the question (‘ask something else’) or to provide support with appropriate prompting (‘to help the pupil’). This sounds like a concise description of effective eliciting techniques.

FAIRNESS

A good teacher, as Michael points out, does not treat ‘weak’ learners less favourably than the better learners. On the level of teacher beliefs, clearly an attitude of fairness is a precondition for treating pupils ‘equally’ and, fortunately, there are techniques which can help in the achievement of this difficult task (Hess: 2001)

After asking young Michael to write his thoughts on what makes a good teacher, I proceeded to ask 100 or so colleagues and friends the same question: who was your best teacher and why? My respondents wrote a brief description explaining their answers which I then summarized according to the key concepts which tended to turn up again and again.

| The Top Ten (Adults) |

| 1 | Friendly |

| 2 | Explained well |

| 3 | A sense of humour |

| 4 | Knew the subject |

| 5 | Patient |

| 6 | Kind |

| 7 | Believed in students |

| 8 | Interesting |

| 9 | Talked about other things |

| 10 | Enthusiastic |

Table 1. Top Ten Characteristics of the Good Teacher (Adults responses)

I ‘triangulated’ these responses, based on young adults and adults’ responses, with a similar survey conducted with young learners by a colleague, Marisa Constantinides; the coincidences were intriguing:

| The Top Ten (Young Learners) |

| 1 | Friendly |

| 2 | Firm but not strict |

| 3 | Motivating and fun |

| 4 | Involves all learners |

| 5 | Humour |

| 6 | Does not burden learners |

| 7 | Passionate, Enthusiastic |

| 8 | Patient |

| 9 | Encourages, rewards all students |

| 10 | Calm and relaxed |

Table 1. Top Ten Characteristics of the Good Teacher (young learner responses)

From these lists, I will focus here on just four characteristics of the good teacher which are common to the two surveys: friendliness, humour, enthusiasm and belief in students.

FRIENDLINESS

It seems the most common characteristic of good teachers, according to the combined responses of learners of all ages, is ‘friendliness’. The concept of ‘friendliness’ is expressed in a variety of synonymous ways (‘nice’, ‘sympathetic’, ‘pleasant’) but whatever the means used, whether verbal or non-verbal, it all adds up to an ability to establish an informal, relaxing atmosphere in which learning can take place. In Krashen’s terms (1982), being friendly lowers the ‘affective filter’ and makes learners more receptive to learning and acquisition.

HUMOUR

Young Michael’s prioritizing of humour, in good teaching, discussed earlier in this article, also finds support in these wider surveys of students of all ages; it is clearly a helpful attribute in keeping learners’ attention and motivating them to learn.

ENTHUSIASM

A positive attitude or even passion for the subject we teach seems to be a universal quality of good teaching. Like being friendly and having a sense of humour, enthusiasm seems to be one of the defining features of good teaching everywhere and all times. It is often said that a teacher’s enthusiasm for their subject be it maths, geography or English, resulted in somebody either being good at the subject or growing to like it, an effect which is said to last a whole life-time.

BELIEF IN STUDENTS

Having confidence in students - and showing it in a number of verbal and non-verbal ways - seems to motivate learners and lead to more successful learning. This hypothesis receives support from research on the importance of teacher expectations on pupils’ performance (Rosenthal and Jacobson, 1982). In young Michael’s terms, the Pygmalion Effect of expectations means not frightening pupils with the fear of failure so often associated with ‘difficult’ tests but encouraging them with responses like: ‘don’t worry, it’s going to be easy’, ‘you’re going to manage it’ and ‘well done’. In sum, we should keep up the flow of praise to achieve positive reinforcement of behavior.

Another landmark in my personal and professional journey in search of the good teacher was an article by Thornbury (1991) which went outside the field of ELT in search of ways of designing better language lessons. Using a questionnaire, Thornbury asked his learner-informants to compare teaching to various metaphors – or similes: ‘a good lesson is like...theatre, painting, music etc’. Good lessons, Thornbury conclude, share features with, among other art forms, good films. They have plot, theme, rhythm, flow, and the ‘sense of an ending’. I replicated Thornbury’s survey with my own students. I distributed the following question, with the instruction to give reasons for their choice:

A good lesson is like....

a play at the theatre / a film/ a painting / a piece of music / a story etc Give your reasons.

|

The metaphors my informants chose, in order of popularity were:

| A good lesson is like... |

| 1 | A game |

| 2 | A play at the theatre |

| 3 | A film |

| 4 | A piece of music |

| 5 | A story |

| 6 | A dance |

| 7 | A painting |

| 8 | A good meal |

| 9 | A driving lesson |

| 10 | Something else |

REASONS FOR METAPHORS

A good lesson is like a game because...

‘Time passes quickly’, ‘Everyone enjoys taking part in the competition; it’s fun’,‘You have to know the rules’, ‘It’s all about learning through co-operation; team-work and learning from others’, ‘The teacher is the referee’, ‘Sometimes you win. Sometimes you lose: in the end you a winner’.

|

The ‘lesson-is-a-game metaphor’ is particularly popular with young learners for the fun, competitive element that defines all games; but some respondents pointed out the need to be co-operative and to follow the rules, if the player/learner is to succeed:

A good lesson is like a play at the theatre because...

‘you play a different role everyday’, ‘teaching is like acting or giving a performance’, ‘the students are an audience who participate’, ‘it is pleasant and gives you knowledge at the same time’, ‘it is difficult and needs a lot of work’, ‘the emotional and mental world of the students; it transports you to another world’, ‘you are curious – you never know what’s going to happen’.

|

The ‘lesson-is-a-play-at-the-theatre’ metaphor’ was chosen because role-playing is involved; others point out the body language aspect (‘we move’), the importance of interaction, participation and communication; some focus on the sheer pleasure arising from wanting to know what happens next. Finally, theatre and good teaching, say my informants, share the appeal to the emotions, cognitive skills and the imagination.

The ‘lesson-is-a-film metaphor’ shares with the ‘lesson-is-a-game-the lesson-is-a-play’ metaphors the prioritizing of pleasure (‘it is thrilling’), role-playing (‘it only succeeds if the participants play their part right’), ‘co-operative students’. However, the film metaphor highlights the role of the teacher as ‘director’ who stimulates the students’ mind and draws on the senses of seeing and hearing.

OTHER METAPHORS FOR THE GOOD LESSON

I was particularly pleased to see that the storytelling metaphor was quite popular amongst students as it seemed to confirm the pedagogic secret of Miss Cooper, my first teacher’s success: storytelling. Stories ‘calm’ the pupils; they make them ‘look forward to the next time’. In practice, this means, for example, beginning each new lesson with a flashback to the previous one. Our lessons, like good stories, should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but ongoing suspense, too.

METAPHORS: SUMMARY

It has been claimed that metaphors shape our everyday lives, the way we communicate but also the way we think and act (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980). If this is true, then looking at teaching in terms of metaphors from the art world, as we have been doing, may help us raise awareness of what happens when we teach well and may also lead to better classroom practice.

I have written elsewhere of the lessons we language teachers can learn from the way music weaves its magic (Prodromou: 2002) and how teachers can weave a coherent engaging lesson drawing inspiration from the techniques of musical composition (theme and variations on a theme, distinct movements but with features in common, variety of tempi, the use of key and modulation, dialogue and harmony between instruments, and so on). I am sure useful lessons can also be drawn from the work of painters, sculptors or good cooks!

Summing up the lessons learnt from comparing good teaching to other real-world aesthetic experiences, we can see a pattern whereby pleasure, co-operation and a clear, engaging structure are important. We need to structure our lessons to create a satisfying whole, which can be achieved by choosing and ordering activities smoothly and with a harmonious flow.

Going back to school to learn a language, or how to paint or even doing yoga, will almost always raise the teacher’s awareness of teacher-student interaction and the whole gamut of qualities and behaviours that motivate learners to learn. I have found learning Spanish from absolute beginner level an opportunity not only to acquire a new language, but to acquire new knowledge about teaching and what it feels like to be a student.

My most recent return to being a learner has been of a more physical nature than learning a foreign language. Five years ago, to combat my chronic clumsiness on the dance floor, and reluctance to get up and dance when everybody else was leaping around in gay abandon, I decided to register for classes in traditional Greek dances. In addition to the useful and pleasurable social skill of dancing, the lessons gave me the opportunity to observe my dance teacher at work; I kept a diary for every session of the first year, noting how the teacher explained the steps and her personal skills and classroom management skills. My aim was to compare her teaching to the work of language teachers, drawing useful conclusions regarding any differences but especially issues and solutions they had in common.

My very first dance lesson brought theory into vivid practice and gave me an alternative first-person experience of the mixed-level class. At home, I wrote my first entry in my dairy in an attempt to capture the group dynamics and my own confused feelings at the end of my first lesson in Greek traditional dances:

Extract 1

| The first lesson...large group of about 30 experienced dancers in a ‘beginners’ class. The speed was dizzying. The instructor fast and furious, displaying his virtuoso skills in the centre of the circle of student dancers. One dance following another at breakneck speed. Νο names, bad acoustics, the teacher’s voice unclear, as he often had his back to some members of the class, because we were in a circle. One bloke seeing my helplessness said, encouragingly: ‘don’t worry, just follow the rhythm’. But later I discovered some of these people had been at it for 3 – 4 years already. I realized I was the only absolute beginner. I left the class half-way through: the instructor followed me to the door and asked me where I was going...I replied: ‘this is not a beginners' class’. |

I decided to change class hoping to find myself with other beginners. I joined my new class and after the first lesson with his supposedly basic dance group, I wrote in my diary:

Extract 2

This class was better: slower, fewer people, with the teacher demonstrating and explaining the steps more. So I watched her feet closely and she would dance close to me, with her back towards me so I could follow. This helped.

But the teacher ‘Efstathia’ did nine dances in the same session. This was a problem: doing each dance once and then moving on -instead of repeating the same dance a few times till it becomes automatic or more fluent.

Large room, the acoustics very bad, couldn’t hear what the teacher was saying.

No names of fellow students.

In the (rare) break, people drift off round the room avoiding eye contact. Quiet. No rapport.

|

The teacher’s technique for explaining the dances was simply to demonstrate them as she talked through the sequence of steps. The teacher’s voice was still not clear enough and the quantity of material was too much for a beginner’s class. There was no ‘getting to know you’ activities using each other’s names so we were all a bit embarrassed to make mistakes and chat to each other in the brief breaks.

The rapport got better as we became familiar with each other’s names and backgrounds. As time went on, I developed a technique for remembering the steps, but the fear of error was still present:

Extract 3

I count the steps of each dance carefully and say them to myself as we dance; this helps with the sequence and rhythm but results in jerkiness of movement; but it’s better than getting the steps completely wrong. The steps and naming them like this is like an explicit deductive approach to grammar rules. Bad for fluency, though but that may come later.

I drifted naturally towards the few males in the group. I discovered their marital status, children, job and how long they had been dancing.

|

As the lessons proceeded, the teacher repeated dances and this proved useful. I also appreciated explicit correction of my mistakes, when it came from the teacher. When my peers corrected me, with all good intentions, it made me self-conscious and my performance got worse, not better.

Extract 4

| The teacher did the difficult dance from last week again and for the first time I realized I was making a mistake when the teacher pointed it out: she had allowed the mistake to fossilize. I’m glad she pointed it out (compare to peer correction by a much better fellow-student...which actually put me off more and made me make more mistakes not less).

|

I’d like to finish this journey with recent research into what makes for ‘expertise’ in language teaching. Borg (2006) sums up 25 years of empirical research into the subject. The expert teacher, according to a wide range of empirical studies looks a bit like this:

- pays more attention to language issues than novice teachers; has/does not have a specific language learning focus

- worries less about classroom management; makes classroom management a matter of routine

- uses her knowledge to make predictions about what might happen in the classroom

- tends to improvise more; makes greater use of interactive decision-making

- makes use of students’ errors.

- is technically skilled and emotionally intelligent.

|

The most recent empirical evidence (Griffiths, forthcoming) suggests that ‘good language teaching’ is characterised by complexity: successful teaching is a multi-dimensional process, shaped by both qualities and behaviours interacting in subtle and unpredictable ways. Effective teaching involves knowledge, beliefs and attitudes which inform behaviour, decisions and choices. Expert teachers are not only experienced practitioners, they are aware of their experiences and practices and they engage in reflection on them to enable them to make appropriate decisions in particular and concrete teaching contexts. Teaching is situated practice. Good teaching involves a never ending cyclical process of action and reflection and a revision of action.

An epigrammatic statement of what recent research into the good teacher reveals might go something like: ‘good teachers are not experts with answers; but practitioners who ask questions’. Successful classroom practitioners have not found a way of ‘being’ good at their job but a way of becoming better at their job.

Thus, just when veteran teachers thought they had reached a safe professional haven, their reputation secure, respected by colleagues and learners, the technological revolution came along to shake us from complacency. Suddenly, all bets were off. Were the traditional concepts of good language teaching still valid in the brave new world of digital devices, digital natives and digital immigrants? A new generation of electronically-driven experts in education have asserted that effective teaching involves, of necessity, the integration of digital learning into our classrooms; good teaching is blended teaching, successful classrooms are flipped classrooms; indeed, the internet with its infinitive store of information and potential knowledge (if not wisdom) has given student autonomy a new meaning, momentum and a dimension: how necessary are teachers, good or bad, when students can find out and learn so much on their own at, the click of a button? How do we re-define the good language teacher in the world of Google and Wikipedia, mass online courses and artificial intelligence? Is it back to the drawing board for research into SLA and effective teaching in the wake of the technological revolution?

The complex nature of good teaching, gorgon-like, goes forth and multiplies.

In sum, the task of becoming a good teacher is never done and has always been, by definition, a process of constant research: as good language teachers we shall never cease from exploration.

In summing up the lessons of my journey in search of a good teacher, I would like to try and identify ten qualities and behaviours that all good teachers seem to do regardless of country or culture based on the various sources we have used in this article:

- they are friendly

- they are enthusiastic

- they have authority

- they have presence

- they are good at explaining language issues

- they are interactive

- they notice their students and their needs

- they have made classroom a routine skill

- they can engage students at a deeper level

- they question what they do

|

These teacher qualities and behaviours happen to reflect my own needs as a student (of Spanish and dance) and readers may ask themselves how this summary reflects their own needs and experiences.

Teachers in distinct contexts, cultural and pedagogic, and with differing personal qualities, will have their own way of realising these deep structures of good teaching: but though circumstances may differ, most good teachers seem to look a bit like the profile above.

The search and research continues...

Alderson, C. & Wall, D. (1993). ‘Does washback exist?’ Applied Linguistics, 14(2), 115-129.

Almond, M. (2005). Teaching English with Drama. Pavillion Publishing Brighton.

Borg, S. (2006). Teacher Cognition and Language Education. Continuum

Dőrnyei, Z. (2001). Motivational Strategies in the Language Classroom. Cambridge

Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of Talk. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Griffiths, C. (2018 forthcoming)

Hess, N. (2001). Teaching Large-Multi-level Classes. CUP

Johnson, K. (2005). Expertise in Second Language Learning and Teaching. Macmillan

Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Pergamon

Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors We Live By. Chicago

Maslow, A. (1954). Motivation and Personality. Harper

Prodromou, L. (1995). ‘The Backwash Effect: testing and teaching’. ELT Journal, 49(1), 13-25

Prodromou, L. (2002). ‘The Music Metaphor’. English Teaching Professional. 24: 57-60

Piaget, J. (1952). The Origin of Intelligence in the Child. Routledge

Rodenburg, P. (2007). Presence. Penguin

Rosenthal, R. & Jacobson, L. (1982). Pygmalion in the Classroom: teacher expectation and pupils’ intellectual development. Crown House

Shohamy, E. (2001). The Power of Tests. Pearson

Thornbury, S. (1999). ‘Lesson art and design’. ELT Journal, 53(1), 4–11

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Primary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary course at Pilgrims website.

|