Far and Beyond the Classroom Routine: Reimagining Famous Paintings

Dimitris Primalis, Greece

Dimitris Primalis has been teaching EFL for 25 years and is interested in introducing innova-tion and change into the daily teaching practice. His experience is shared in his columns in the ELTeaser (Tesol Macedonia -Thrace, Northern Greece newsletter) and the BELTA bulletin. He works at Doukas primary school in Athens, Greece.

Menu

Introduction

Activating creativity and imagination

Practical tips

Some closing thoughts

References

Have you ever wished you had Hermione Granger’s potions and magical skills to deal with demotivation and classroom boredom? Well, maybe you already have the ingredients and skills to do it. Can learning technology, creative and critical thinking skills and learner engagement act in synergy to motivate learners and develop language skills? If so, how can this be achieved without straining the syllabus or devoting valuable classroom time allocated for other learning aims? A possible answer is a project on art. If you are thinking that I will refer to tedious tasks, such as “Find information about your favourite painting and present it in class”, you are mistaken. Projects like these guarantee only two things: utter boredom in class and powerpoint slides with long, copied and pasted texts that learners will not even have bothered to read before presenting it in class.

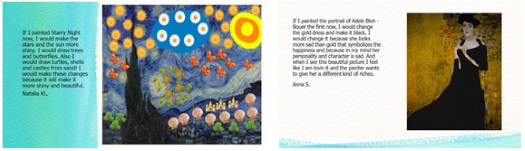

I was tempted to “tweak” the above-mentioned task and make it more challenging for my learners. Having been told about the trend of re-imagining famous paintings, I decided to rephrase the task as follows: “Find information about your favourite painting and re-imagine it. You can draw or use technology to make your version of the painting. Write a short text and describe why you have made changes and how you feel.”

Stage 1

I showed in class Vermeer’s Girl with pearl earring and its humorous “Star Wars” version and explained the notion. We even searched on the internet other “re-imagined” paintings and the students found the task intriguing. To my surprise, none chose to draw it and they all chose to use technology. Some used “Photoshop”, others used apps that sounded alien to me. However, they all produced their version of their favourite painting and wrote a text about it.

The problem that arises at this stage is that teachers need to collect the students’ work and give them feedback. I created a virtual notebook on ®OneNote and invited students to share there, photos of their drawings, information about the paintings and their reflective accounts on the changes they made. If the school does not support Windows, you can use any other collaborative web 2.0 tool like “padlet” or “linoit”. Alternatively, you can even have them in a USB drive. Once you have collected all the material, you can put everything together in a video like this one:

Reimagining famous paintings

The original idea to create a virtual museum using ® Minecraft came unstuck as the 5th graders who promised to do it, failed to meet the deadline. However, all the students cre-ated their re-imagined paintings. Beyond the artistic value, I was happy as an EFL teacher because all the students produced texts in L2 – some short, others longer and more elaborate. The structure used predominantly was the 2nd conditional, but there were also chunks of lan-guage which were closer to freer practice and the more creative use of the language.

Stage 2

But that was not all… As we were discussing the project, issues arose like:

Is it a good idea to re-imagine paintings and create our own version?

Does it make us more creative or does it show disrespect for the artist and the work of art?

These triggered heated discussions in class and on the school's Learning Management System, which were a source of inspiration for the next part of the project: An opinion poll.

In the meantime, an English teacher openly opposed the idea while the art and crafts teacher was in favour, which gave me the opportunity to do a follow-up on the topic. I divided the class into two groups. Group A interviewed the teacher who was against and Group B the one who was a supporter of the idea. Then, the class listened to both recording and wrote down the arguments of each side. If you work at a language school that has only foreign lan-guage teachers, learners can ask other English teachers to express their opinion. This was a great opportunity for me to introduce small argumentative paragraphs with a topic sentence, the argument and example. For instance:

“I believe that reimagining famous paintings is not a good idea. First of all, we do not know exactly what the artist wanted to show and how he or she felt. For example, I cannot feel the same like Munch when he painted the Scream.”

This may not seem much of an accomplishment, but for 10-11 year old pupils, supporting their views with reasons and examples is not an easy task.

Finally, after doing a unit in the coursebook on art, I asked my students if they knew about any special stories behind a painting or work of art. Even though I had originally feared that my students had mechanistically copied and pasted information about their favourite work of art, it turned out that some of them had paid attention. A few days later, A. K. came to class with a video she had created that narrated the story behind the “Starry night”:

The story behind the painting

So far, my students had read, listened, spoken and written in English about a different sub-ject (CLIL) and above all were motivated and felt creative, taking initiatives like the video produced by A.K.Yet, there seemed to be one more element missing. Their own personal cre-ations. We had a discussion in class about how interesting it would be if the artist could talk about work of art, what inspired them and the feelings they experienced while creating it. Then, I asked them to create their own work of art and write a paragraph or shoot a video to talk about it. Here is a sample of their work:

My work of art

Video created by M.M.

If I was asked to give practical tips to colleagues who would like to try it, I would say:

- The focus is not on the aesthetics but on the content and the output produced by learners.

Therefore, all works of art are acceptable.

- Make clear that it will have to be their work of art. Remind them that you can search

images on the internet and find out if someone else has created it before them. Copying

and pasting the image will deprive them of the pleasure of being creative.

- Introduce the notion of editing by telling learners that their work will be exhibited or

hosted on a website. Thus, their work needs to be without typos or errors.

- Appoint assistants especially when it comes to dealing with technical difficulties. Some

kids may be more into technology than you are and it will encourage them to be more

actively involved in the project.

- Display the outcome of their work at school and/ or on the social media. On the latter,

ensure that no personal data is exposed. Sharing their work acts as recognition of their

effort and will help them build confidence.

Personalizing art and giving the learners the opportunity to express their own views stimulated creativity and language production, initially predictable and structured and in later phases, free production that conveyed the learners’ thoughts and feelings. Technology has acted as a stimulus to engage learners. It is worth mentioning that learners opted to use tech-nology, even when they could have used pencils and paper. This project also motivated learn-ers who were previously indifferent. Most of the work was done at home by the pupils and I felt that the time we devoted in class was well spent.

The project entailed all the four “Cs” of CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) (Coyle,2009):

- Teaching content, namely Art.

- Communication as they had to write and talk about their work and a controversial is-sue.

- Cognition, in that creative and critical thinking skills were practised.

- Culture as they found more information about the background of the artists and the era they lived in.

Thanks to all the above, learner interest was stimulated, a meaningful context was given in-stead of cramming their heads with long lists of words, and genuine communication to ex-press feelings, ideas and support views was generated.

Reflecting further on the reasons why the project sparked learner engagement, I feel that adopting an “out of the box” approach, personalizing the task and encouraging students to use technology creatively played an instrumental role.

It also acted as a stark reminder that far and beyond the grim routine of grammar and syntax, learning can be approached in a more holistic way that can motivate and engage learners.

Finally, I would like to thank Maria Karantzi and Annette Morley for their help and support!

Coyle, D. (2009). Promoting cultural diversity through intercultural understanding: A case study of CLIL teacher professional development at in-service and pre-service lev-els. Content and language integrated learning: Cultural diversity

Primalis, D. (2017). Reimagining famous paintings: Stimulating creative and critical thinking in the EFL class through an art project. A different side of EFL. Retrieved from http://differentefl.blogspot.gr/2017/08/reimagining-famous-paintings.html

Please check the CLIL for Primary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the CLIL for Secondary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Practical uses of Technology in the English Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Practical uses of Mobile Technology in the English Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

|