Editorial

This article first appeared in Modern English Teacher, Volume 21/3, July 2012

Getting to Grips with Texts

Simon Mumford, Turkey

Simon Mumford teaches EAP at Izmir University of Economics, Turkey. He has written on using stories, visuals, drilling, reading aloud, and is especially interested in the creative teaching of grammar. E-mail: simon.mumford@ieu.edu.tr

Menu

Introduction

Ten synonyms

The text as answer key

Find the paraphrased sentence

Reading aloud with emphasis

Synonym dictation

Timed Reading

Which paragraph?

Blocking sentences

Text summary

Key words

One word one paragraph

Conclusion

For advanced/EAP students, texts of over 600 words are common. Although the principle reading skills remain the same whatever the length of text, longer texts invite different treatment for a number of reasons. Their length means that not all of the text will be read with the same level of detail, but it may be desirable to focus intensively on certain key sections and more extensively on others. Also, with longer texts, there may be a need to revisit the text after a first reading, for language exploitation or to move from general meaning to focus on details. Furthermore, a course which includes a series of longer texts demands a greater range of activities to ensure interest is maintained. There follows a number of suggestions for intensive and extensive reading activities, using a variety of techniques, including dictation, reading aloud, summarising, scanning, paraphrasing and grammar exercises.

Choose about ten words that are difficult for students from a single paragraph. On the board, write synonyms for these words in the order that they appear in the text. Note that if the words in the text are academic or low frequency words, the synonyms should be words that students are more likely to know. Ask students first to find the paragraph they are from. It should be easier to identify a block of related words in one paragraph than a single word. When they have found the paragraph, ask students to match each synonym with the original. Once they have identified one or two words, the others should fall into place.

The text can be used as an answer key for any kind of grammar activity. Take a stretch of text and create a cloze test by removing some words. When students have done the test, they check their answers by scanning the text for the original version. Similarly, this approach can be used with a variety of exercise types, e.g. mixed up sentences, putting the verb in the correct tense, putting in the punctuation. Such exercises can be used as a pre-reading activity, in which students are making predictions when, for example they put words in order, or as a post reading activity, where such activities could be used to focus attention on particular information or language, as a follow up to a more extensive reading of the text.

Paraphrase a number of important sentences in the text and write them on the board. Make them easier to understand than the originals. Ask students to find the originals in the text and underline them. Then ask students to look at the originals and paraphrases identify pairs of synonyms, and to notice how similar meanings are expressed through different grammatical structures, but also how the meaning of the original can be implied through very different strategies other than straight-forward paraphrasing at word or phrase level. For example, the sentence It is apparent that video games today share no resemblance to the games of the past, can be paraphrased as Clearly, current video games are very unlike the older games, a sentence which has clear parallels with the original. The sentence Video games have completely changed over a period of 20 years is rather different structurally, but conveys the exact same meaning.

Read a paragraph aloud to students, using intonation, stress and volume to emphasize what you consider to be the important points. Ask students to underline the important points while listening. The more you emphasize words or phrases, the more they should highlight the words (eg by pressing harder with the pencil, double underlining, or using a brighter colour). Then ask students to reproduce your reading, using their underlinings as a guide. As well as giving students a model for reading aloud, this activity could lead on to a discussion of the important points of paragraph and perhaps, the writer’s point of view and your attitude to what the writer is saying.

Choose a difficult paragraph. Tell the students you are going to read the text, but you are going to change some of the words into easier synonyms. Students listen as you speak. Then ask them to write any synonyms they remember above the originals in the text. After a minute or two, let them work in groups to complete the exercise. Ask one student to read the new version aloud to check all synonyms have been noted.

Choose a paragraph and ask students to predict the amount of time it will take to read aloud. Then, ask them to read it aloud, note the time taken and compare with their guess. Now ask them to read it again, silently, again timing themselves. Finally, explain any words that might block comprehension before asking students to read silently again, again noting their time. They should find the third reading to be the fastest. This illustrates three aspects of being an effective reader, i.e. not vocalising (or sub vocalising), familiarity with the text and the skill of reading in general, and vocabulary knowledge. When they have finished, ask students to count the words in the paragraph and work out their reading speed per minute. As a guide, according to the Cambridge University Students Union website, college students read non-academic texts at 250-350 words per minute on average, and a good speed is considered to be 500-700 words.

After students have read the text, list the paragraphs on the board. Give each a title, eg general introduction, background to the problem, details of the problem, first solution, second solution, future innovations, conclusion. Ask students to close their books. Now read a sentence at random. Students should be able to identify the paragraph it comes from simply by listening. After several examples, ask the students to work in groups or pairs.

Choose a long and complex sentence from the reading, and ask students to break it up into blocks of 1-6 words. If they do this correctly, it should help them understand the sentence. Students can then be asked to identify which blocks are more important for the meaning of the sentence. Here is an example, with two less important blocks eliminated: (other solutions may be possible)

The other end / ducks / under a six-lane steel suspension bridge, / one of Bilbao's main cross-town arteries, / and comes up the other side, / finishing in / a high limestone-clad tower / that serves no other function / but to wrap / the bridge / and its constantly humming traffic / into the structure / of the museum itself.

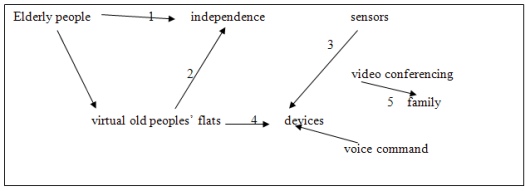

This diagram represents a summary of a reading text on high-tech devices for the elderly. The words represent themes in the reading texts, and the arrows show the relationship between them. Ask students to identify the relationships between the words, for example: 1 Elderly people want independence, 2 The flats allow independence, 3 Sensors activate devices, 4 The flats are equipped with devices, 5 Video conferencing allows contact with their family. Ask students to suggest more words/connections. Note that the words in the diagram are all nouns, and the arrows represent verbs.

Give students a number of key words from the text and ask students which word occurs the most times. Ask them to scan the text, but not count before guessing. Ask them to rank the words by frequency, before checking their answers by counting. The answers should reveal what the text is really ‘about’.

Finally, here’s a fun way to end a reading lesson. Put the students in pairs and tell them to make sentences by saying one word at a time from successive paragraphs, so student A says a word from paragraph 1, student B from paragraph 2, student A from paragraph 3 and so on. The sentences should be grammatically correct, but of course they may be a little illogical.

When approaching longer texts, one approach that seems to work well is a focus from general to specific, and then back to general. Start with a general focus on activities that involve scanning the whole text (e.g. The Text as Answer key, above). Then students work on detail on certain sections or paragraphs (e.g. Synonym Dictation, above). Finally, by switching back to a more general focus (e.g. Text Summary, above) we can put the detailed work back into the context of the whole text.

Longer texts present challenges to both students and teachers. Authentic texts that are long and difficult means that the teacher may need to find quick ways to simplify meaning to help motivate students to work with texts which otherwise may be considered daunting. Also, more substantial texts represent a considerable investment of students’ time and effort in reading and understanding. Therefore, in order to capitalise on this investment, there is a need for a greater variety of activities that extend and consolidate students’ understanding.

Academic Speed Reading, Cambridge University Student Union

www.cusu.cam.ac.uk/academic/exams/speedreading.html

Came, B. and Branswell, B., Gehry's Bilbao Museum Sensation (Nov 97 Updates)

www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/gehrys-bilbao-museum-sensation-nov97-updates/

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|