Editorial

Another article by the author along similar lines can be found at

www.academia.edu

The Transactional Analysis Motivation Model as a Framework of Reference for Teachers and Trainers

Paolo Torresan, Italy

Paolo Torresan works as an Italian as FL teacher and teacher trainer. He is Editor-in-chief for the following journals: Officina.it and Bollettino Itals. He wrote: The Multiple Intelligence Theory and Language Teaching (Perugia 2010); Didáctica de las lenguasculturas (& Manuela Derosas, eds.; Buenos Aires, 2011); Il noticing comparativo: la grammatica a partire dall’output (& Francesco Della Valle; Lincom, München, 2014). E-mail: esh@unive.it

Menu

Berne’s model of motivation

The over-arching hunger: balance

Revisiting Berne’s model: the fourth component adopted by Meredith

Berne’s model and the teacher trainer

Berne’s model and the language teacher

Conclusion

Bibliography

Transactional Analysis [henceforth referred to as TA] holds that human behaviour is driven by three psychological hungers (Berne 1961: 78-80):

- structure;

- recognition or acknowledgement or certainty;

- stimulation

What requirements rely upon these hungers? What is their nature?

- Doing, that is, a propensity towards action, varied stimuli, discovery, physical, emotional and intellectual contact with others, experimentation, instead of monotony and passivity;

- Feeling recognised and having a sense of belonging to something or someone, enjoying the group’s recognition of one’s abilities, expressions, initiatives, instead of a sense of isolation and lacking recognition;

- Feeling certain, operating in contexts with clearly-defined roles, time-scales, objectives, leadership assignation, rules, instead of a sense of abandonment, a lack of order, direction or boundaries.

Each of the three hungers has a dimension that concerns the learner's relation to the world, to things and people and an equally important internal dimension. Let us consider the observations formulated by Mario Rinvolucri (2010) directly:

“The first human hunger […] is STRUCTURE. Let us look initially at EXTERNAL STRUCTURE […]. Without structuring of space, time and activity a human being goes to pieces. A housewife preparing a meal is structuring her family’s eating experience. When you prepare a lesson you are bringing prospective order to your classroom. As your gaze moves over these lines you are experiencing what to you is the external structure that I am imposing on these words as I write them.

The other sort of STRUCTURE is internal, the structure you offer yourself. If you go to a lecture you may decide to listen and retain what you hear, you may decide to take summarizing notes or you may decide to scribble down as much as you can of the incoming text.

If the lecture is sufficiently boring you may start thinking of the lecturer without any clothes on or you may sweep into a daydream unconnected with the lecture.

All of this is internal structuring and we spend most of our waking day, often unconsciously, giving ourselves structure […].

The second human hunger that Eric Berne posits is STIMULATION. Think for a moment about the amount of sensory stimulus you are receiving right now as you read this. In my own case, as I type , I can feel the faint resistance of the keys I am pressing on, the computer is humming and a clock is ticking somewhere in the room. Two lamps are flooding my work area with light.

The importance of sensory stimulus becomes clear when you deny it to a person, as happens routinely when prisoners are hooded and forced to wear heavy earplugs in places like Guantanamo Bay or Belfast. After 48 hours most victims of hooding begin to manifest grave schizophrenic symptoms.

Of course there are many forms of external stimulus: a book that grips you, a view which enchants you, a film that fills you with dreamlike images.

Equally important is INTERNAL STIMULATION. You go for a walk and find that ideas are popping up all over the place and that your dialogue with yourself is rich and fascinating. In this case you are enjoying internal stimulation. I am sometimes amazed at the brilliance of the odd night dream I remember. I really feel that my inner dream-maker has an intelligence that by a long way surpasses what I am consciously able to mentally create […].

The third human hunger […] is RECOGNITION or ACKNOWLEDGEMENT […].

EXTERNAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENT is when the mother smiles as her toddler manages to clamber up a high step, or when she beams happily as the child comes out with a complex sentence […].

INTERNAL RECOGNITION or ACKNOWLEDGEMENT are what Nelson Mandela is talking about when he says you have no right to fail to realize and respect your own talents, your own genius. I certainly know people who are happy with their successes and equally I know others who find it almost impossible to accept the worth of their own work. Think of perfectionists you have come across for whom too much is not quite enough. Inability to acknowledge their own achievements and excellence is a heavy burden for a person to bear”.

Many myths can be understood in light of the three psychological hungers.

The platonic demiurge, the intra-Trinity foundation of Christianity, the universe created according to number, weight and measure as described in the book of Proverbs, express, respectively, stimulation, recognition and structure at a metaphysical level.

In parallel fashion, the definitions of man as homo faber (in the Renaissance), as a social animal (in Aristotle), as a being endowed with the power to give names to things (in Genesis), place stimulation, recognition and structure within the very essence of humanity.

The three hungers are thus the lenses through which we construct our representation of the world and ourselves. In this regard, Mario Rinvolucri employs the terms thinking frames and mental filters (2010).

The work of Illsley Clark and Dawson (1998) has shown that – apparently going against Maslow’s needs hierarchy – the desire to satisfy the hungers is so consuming that individuals may neglect physiological requirements such as eating and sleeping in favour of pursuing their satisfaction (examples might include an artist’s absorption in completing a work, a scientist’s ongoing research or hunger strikes declared by political protesters).

Satisfying the hungers to the correct degree causes the release of energy, which imparts a feeling of well-being, or indeed direct pleasure, to the individual. Well-being is achieved through a harmonious interaction among these variables.

Conversely:

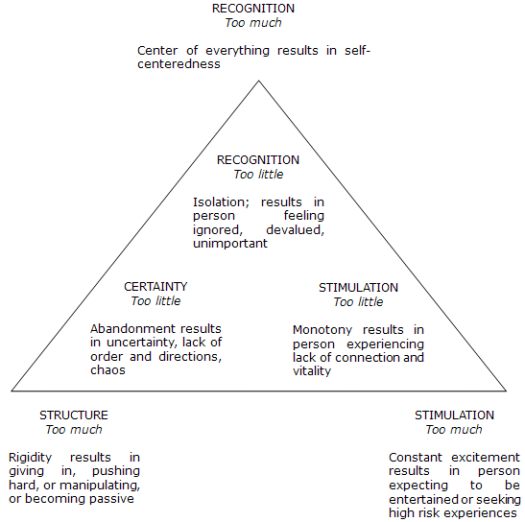

- excessive structuring confines through rigidity, leading to a state of passivity;

- over-stimulation leads to saturation (the learner feels he/she cannot cope with so many stimuli or with the excessive exposure to a single type of stimulus and enters a state of exhaustion);

- excessive recognition may conceal manipulatory strategies.

Similar unease can be experienced in situations where elements are lacking:

- weak structuring engenders a situation characterised by uncertainty and chaos;

- lacking attention gives rise to self-devaluing behaviours;

- weak stimulation produces boredom, loss of vitality (cf. fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Balance of hungers (adapted from Illsley Clark, Dawson 1998: 18)

Situations characterised by unease are particularly delicate when observed in cases of non-recognition, excessive recognition or intermittent recognition. Those who are not recognised, in turn, fail to recognise themselves: they cannot understand who they are or what they want. Excessive recognition, which shares characteristics with manipulation, confers the same effect, as does intermittent recognition, characterised by a two-fold affective code (double bind: “I accept you”/ “I do not accept you”, or “I accept you, provided that”).

Illsley Clark and Dawson’s work comes to equate recognition with unconditional love (1998: 24; my emphasis):

“Giving someone the gift of unconditional love doesn’t mean always agreeing, or accepting any behaviour no matter how hurtful, or accepting substandard performance or tasks, or hide our anger. It does mean being honest, working through differences, negotiating an renegotiating agreement, holding one another accountable, and staying respectful in the process”.

The lowest common denominator of every act of recognition consists in a form of attention: the person feels recognised in so far as he/she is seen. This is a view currently held by many educators: the educative relation takes priority over teaching itself.

Now, a dynamic balance is established among the three needs, and there could be a sort of compensation when a need is unfulfilled. For example, the sense of unease engendered by lacking recognition may be alleviated by doing (hyper-stimulation), since it is in doing that the subject feels recognised, or rather feels recognised for what he/she does. Subsequently, however, should the conditions allowing for doing be removed, this may induce unexpected feelings of uselessness in the subject.

Illsley Clark and Dawson describe a training experiment illustrating dynamic balance (1998: 17; my emphasis):

“Have you attended a meeting where the structure was so unclear that it took a whole morning for the group to decide what to do? William, who attended just such a meeting recently reported on how people responded to the uncertainty.

Some people addressed to the lack of certainty directly:

- Can we set some goals and get going?

- Let’s divide up into smaller groups and decide what to do.

- We could do this just like we did the last time.

When that didn’t work, some people tried for recognition:

- I feel uncomfortable because we haven’t introduced ourselves.

- I need to change room.

- Can we wear name tags?

Some people raised the stimulation level by doing a lot of side talking, pointing out of the window, interrupting, and disagreeing with everything. After a structure was finally created, when goals were identified and a way to meet them was constructed, individuals settled down and the group went about its work and play”.

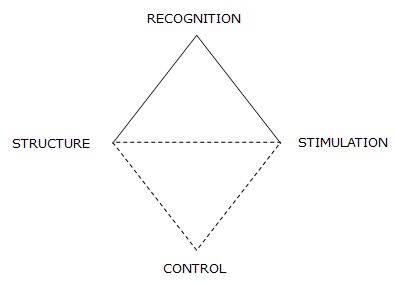

Recently, Meredith (2000) proposed the addition of a fourth factor to Berne’s model: control.

By consequence, the hungers triangle described by TA would be altered to take the form of a diamond (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Integration of the control component into Berne’s model (version n. 1)

Let us now review the study’s observations (Meredith 2000: 285-286):

“One day while visiting my daughter-in-law and two-year-old granddaughter, Tanya, I witnessed a wonderful example of this striving for psychological control. Tanya, in her high chair, asked for a drink of water, which her Mum promptly gave her. Tanya pushed it away. There then followed half a dozen «I want water»/«No» transactions as frustrated Mum attempted to get Tanya to make up her mind. Meanwhile, Tanya looked quite satisfied at proving how powerful she was, with her demeanor only changing when Mum finally gave up. Then Tanya tried another control mechanism as she burst into tears and had a tantrum.

With reference to Berne’s three hungers, it can be argued that Tanya was obtaining stimulus (strokes) and recognition and was doing something with her time. On the other hand, developmental psychologist might argue that Tanya was going through a normal developmental stage. For example, Erickson (cited in Zimbardo 1979) would say she was in the stage of autonomy versus doubt with the goal being to achieve a «sense of autonomy, adequacy and self-control» (240-241)”.

It concludes as follows (2000: 286; my emphasis):

“I equate this with Tanya exercising her psychological control «muscle». Depending on how successful she perceives the transactions to be, Tanya will add to her repertoire of positive control methods: a sense that it is OK to have needs, to ask for hers to be met, and, most importantly, for other people to have needs as well (e.g. there are limits, mother cannot be expected to keep dancing to my tune forever). Alternatively, Tanya may see her tantrum gave her a sense of power, and she will add this to her neurotic control repertoire”.

The American psychologist upholds the view that control is built up through experiences of empowerment (understood as the ability to act effectively and harmoniously with oneself, others and the world), stability (understood as the ability to maintain a flexible conception of one's self image, that of others and the world, as each evolves over time) and connection (understood as the ability to feel sustained by a relation and not feel excluded or threatened).

The inability to exert control leads to counter-posed situations: respectively, helplessness, confusion and a feeling of isolation.

In such cases, the subject may react by exerting neurotic/negative control, which is a caricatured form of positive control: the subject reveals a desperate need to impose his/her views, as this is the only alternative to giving in to the feeling of being at the mercy of others, of being confused and left alone. These behaviours are observed in bullies, for example, who manifest “discounts and exploitation of self, others and the environment”, and employ an array of aggressive and manipulatory signals, both verbal and non-verbal (285).

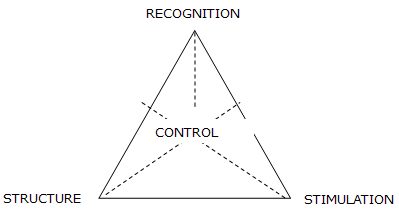

This paper supports the view that the concept of control adopted by Meredith figures as an interiorization of structure, stimulation and recognition. That is, rather than entering the subject ab extra, the variable is engendered ab intra: it is formed from the first three. Parallel to the subject’s gaining of confidence with his/her surroundings, by way of structured experiences allowing him/her to keep anxiety at bay, recognising him/her, and allowing for the enjoyment of successes with regard to stimuli management, a sense of self-regulation develops, that is, of control and thus autonomy.

Armed with a perception of who, what and how – or indeed who he/she is (recognition), what he/she wants (stimulation) and the strategies required to obtain it (structure) – the subject attains self-efficacy and gains a positive image of him/herself and the outside world.

When the terms who, what or how become less clear or well-defined, we observe a depreciation of control.

Overall, Berne’s model is enriched by Meredith’s contribution not so much by the introduction of a fourth factor as by her identification of the point of intersection of the tri-polar motivational structure. Rather than forming the corner of a diamond, the term control defines the balance among Berne’s three hungers. Thus control represents the point of convergence of the facets of a pyramid whose base is formed by the psychological hungers (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Integration of control component into Berne’s model (version n. 2)

The TA model may provide a useful framework for trainers in view of:

- having trainees reflect on the means by which they achieve structure, recognition and stimulation in class. Such reflection may also be carried out using a check-list (Illsley Clark and Dawson 1998: 6):

- “Am I providing a balance of stimulation, recognition, and certainty for my children?

- Is one of them easier for me to offer so that I offer it at the expense of the others?

- Is one of my children clamouring for me to meet one of the hungers because she isn’t getting enough of another? […]

- Am I putting one of my unmet hungers onto the children instead of noticing what they need?

- Do I have stimulation, recognition, and certainty balanced in my own life?

- Am I accepting the satisfaction of one hunger in place of another when I could do something to get that hunger met directly?”

- considering the ways in which they themselves manage their hungers throughout the various learning contexts and how the attention given to each of them can be modified according to whatever variables may come into play (for example, their mood and physical state; whether the trainees are LS or L2 in-service teachers; the length of the teacher training course; the topic covered; whether they work alone or with a colleague, and with whom, in that case; etc.).

They may also consider:

- Has the balance of the three hungers evolved over the course of my career as a trainer? If so, in what way?

- Are there any specific actions undertaken by the best trainers/teachers that I have had that have left a lasting impression? Are they related to Berne’s three hungers?

- Have I witnessed messages given by other trainers or teachers which fail to respect the three hungers?

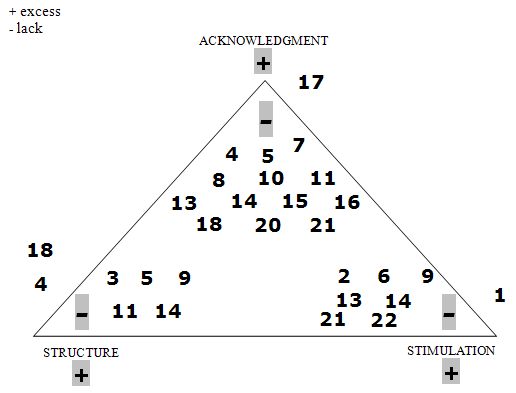

The below introduces a list of behaviours that fail to respect the psychological hungers of trainee teachers (as we will see, some of them have a negative impact on the satisfaction of multiple needs).

Fig. 4. Behaviours failing to respect the psychological hungers of trainee teachers

- Information overload. In his/her attempts to say it all, the trainer says too much, covering many topics in a superficial manner (excess stimulation);

- Lacking originality. The trainer relies on traditional techniques and fails to offer his/her own observations (lack of stimulation);

- Lack of reflection around activities (debriefing). No meta-knowledge is created. The trainer does not find answers to questions like: “What is the point of this activity?”; “How does it link to other activities?” (lack of structure);

- Misguided use of resources. For example, having music on in the background for activities requiring concentration. In such cases, has the trainer checked that the students are happy? (lack of recognition; excess structure);

- Failure to respect deadlines. The trainer neither respects nor ensures respect for deadlines set for activities (lack of recognition; lack of structure);

- Lack of critical perspective. The trainer uses black-and-white thinking, without justifying his/her stances or ignoring the complexity of certain issues (lack of stimulation);

- Top-down communication. The trainer treats the trainees as ‘students’ in a Parent-Child relationship (lack of recognition);

- Undue assumptions. The trainer makes assumptions or generalisations regarding the trainees’ moods. For example, he/she may say “I can see you are tired,” without verifying whether this is truly the case (lack of recognition);

- Imbalanced activity management. Overly long discussions; interruptions to ‘flow’; too many lecture-style presentations etc. (lack of stimulation; lack of structure);

- Trainer fails to remember students’ names and/or prepare enough activities to create and consolidate the group (lack of recognition);

- No thinking time. The students are not given enough time to review information, ask questions, take notes (lack of structure);

- Tolerance of stereotypes. The trainer may tolerate stereotypes or even use activities involving the formation of stereotypical judgements of people (labelling; lack of recognition).

- Overly abstract information. Lack of link between statements and methods with the teachers’ working reality (lack of recognition; lack of stimulation);

- Poor preparation and attention to detail. The session does not have an organic structure; the trainer seems poorly prepared (lack of recognition, of structure, of stimulation);

- Lack of coherence. The trainer’s practice is not coherent with what he/she advises (Woodward 1988). For example, encouraging trainees to be relaxed about errors, while feeling embarrassed or guilty at his/her own errors (lack of recognition);

- Use of activities not guaranteeing the participation of all. This may involve in-class exchanges where not all can participate (lack of recognition);

- Indiscriminate praise. The trainer gives out ‘too much’ recognition; excess praise appears inauthentic and gratuitous (if everything is ‘great,’ how is excellence recognised?) (excess recognition);

- Rigidity. The trainer sticks to the course plan to the letter, paying little or no attention to the trainees’ questions (excess structure; lack of recognition);

- Allowing or encouraging a few students to speak on the group’s behalf. If one of the trainees says he/she is unsatisfied with the course, the trainer requests or allows others to come to his/her defence without investigating the area of dissatisfaction (lack of recognition);

- Student preference. Either verbally or non-verbally, the trainer values some students’ contributions more than others (lack of recognition);

- Over/underestimation of abilities. E.g. providing tasks designed for novice teachers in a course attended by experienced teachers or vice versa (lack of stimulation; lack of recognition).

As teachers, we can ask ourselves which need any specific action we take is targeting. Let’s consider some examples.

Recognition

Recognition requires the building of rapport, an empathetic relation between participants, through group bonding and trust activities.

In addition to this, the teacher promotes recognition by giving each learner the opportunity to speak to others about him/herself, simultaneously refining his/her own listening skills. Similar practices such as using students’ first names, finding links between topics covered and students’ lives and leaving time and space to let anyone to find his/her own pace provide opportunities for recognition to be built upon.

Similarly, creative activities which educate learners on self-expression through symbolic representations (through drama, pictures, objects, etc.) provide opportunities for recognition.

Structure

Structure entails gradualness, applied to language, skills development, task and text complexity.

Repetition is a factor that contributes towards structure too.

Even routines, follow-up activities, and any action aimed at contributing to organising what has been learnt help to impart a sense of certainty.

Stimulation

Stimulation refers, above all, to the idea of variety, that is, multiple opportunities for physical, social, personal and cognitive involvement.

Variety in language teaching may concern: the type and duration of activities; activity types (such as: pedagogical or authentic tasks; exercises to work on at home or continue in class; sedentary tasks or those requiring movement, etc.), textual type and genre; sequencing models, etc.

Control

It has been argued that control is achieved via the satisfaction of the basic hungers. Wherever the three hungers enter into dialogue, control can be developed.

Nonetheless we must pose the question: are there types of teaching strategy capable of forming a sense of control in students per se?

Considering three elements involved in any process of language education – student, language, methodology – we uphold the view that the control ‘muscle’ can be trained through (just as examples):

| student |

language |

methodology |

| opportunities for learners to exercise self-determination (choosing from various options) and take initiative (the ability to think up options), either in the context of individual projects or in collaboration with peers. |

noticing activities, which lead students to discover the language’s regular features and to simultaneously update their own conception of how the language works. |

metacognitive activities, through which students plan, monitor and evaluate learning processes and express judgement on educational resources. |

This discussion has illustrated the three psychological hunger-theory formulated by Eric Berne, with a digression on recent additions suggested by Meredith.

The model has been seen to provide a useful tool for teachers and trainers.

Berne E., 1961, Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy, Random House, New York.

Illsley Clark J., Dawson C., 1998, Growing Again: Parenting Ourselves, Parenting Our Children, Hazelden, Center City, MN.

Meredith K., 2000, “Control: The Fourth Psychological Hunger”, Transactional Analysis Journal, 30, 4.

Rinvolucri M., 2010, “Thinking Frames to Use in Our Teaching Learnt from Eric Berne, Transactional Analysis, and Rudolf Steiner, The Waldorf Movement”, 2009 English Teacher Symposium, Language Centre of the UEAH [forthcoming].

Woodward, T. (1988). Loop-input: A New Strategy for Trainers. System, 16, 1, 23-28.

Zimbardo P. G., 1979, Psychology and Life, Scott Foresman, Glenview, IL.

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Building Positive Group Dynamics course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|