The Process of Implementation of Bilingual Education Programs in Chosen Primary Schools in Europe

Barbara Muszyńska, Poland and M. Elena Gómez Parra, Spain

Barbara Muszyńska is an educational psychologist and an ESL teacher and teacher trainer with hands-on experience of teaching English to younger learners, university students, as well as teachers. She is a committed ESL materials writer for the Macmillan Publisher (at both, primary and lower-secondary level). She has also worked for six year for Pearson Publishers as a teacher trainer and materials writer. Her main interests CLIL and the multilingual and intercultural education in Europe are related to her PhD research at the University of Cordoba in Spain. E-mail: basia.muszynska@gmail.com

M. Elena Gómez Parra, PhD. Lecturer of English at the Dpt. of English and German Philology at the University of Córdoba, Spain. MD in Distance Education. Graduated from the University of Granada (Spain). Her research lines are focused on bilingual and intercultural education. She teaches CLIL and English in Teacher Education (English) and Intercultural Communication and Academic Writing at Master’s Level. She has had some research stays in the USA (Univ. of Berkeley; Bowdoin College) and the UK (University of Manchester). She has coordinated the English and German sections in the Language Centre of the University of Córdoba (2000-2006) and she has been the Ass. Dean for International Affairs at the Faculty of Education (2006-2014).

Menu

Introduction

Background

Effective dual-language curriculum

Methodology

Results and conclusions

References

In today’s globalized world, we have come to value the significance of ideas, creativity, intelligence but also the ability to communicate freely. Nowadays educational systems need to adapt to the changes that take place in our societies. In bilingual education, the content is closely related to the notion of modern times, and it has been said to be linked to the way our brain learns (Coyle, Hood & Marsh, 2010).

The benefits of dual-language focused education are profound. The evaluations of the effectiveness of bilingual schools and recent reviews indicate relative success of such programs (Cazabon et al., 1993; Genesee et al., 2006; Howard et al., 2005; Krashen, 2004; Lindholm-Leary, 2001). Cultural knowledge modifies conceptual representations and organizations in bilingual memory. New connotations and new meanings may develop in such process (Vaid, 2000). Training learners to think in a different language promotes the development of their mental processes and conceptualization. The newly developed conceptual representations may allow bilinguals to see the same phenomenon from different perspectives. Those new conceptual and lexical representations may foster cognitive flexibility, divergent thinking, and creative ways of retaining experience (Kharkhurin, 2007).

Nevertheless, decisions concerning the start of bilingual education cannot be based on a popular saying ‘the younger the better’. In fact, there is very little evidence for a ‘critical period’ hypothesis, apart from the development of a native-like accent (Garcia, 2009). Adults are also capable of becoming bilingual. For this reason, second language programmes in schools should be based on realistic estimates of how much time during a school week is needed for the process of second language learning to take place. One or two hours a week is not sufficient amount of time to educate bilingual learners, no matter how early they start. Cummins reminds us that the time with our students needs to be spent on meaningful instruction, as it is more important for students’ linguistic success than simply teaching through one language or another.

Dual-language education programs in Europe vary. They are interdependent on factors such as students, teachers, the local community, or the political system of a country. They also depend on language goals, such as whether the aim is bilingualism or developing proficiency in a second language, which influences the amount of time spent on instruction in a second language. Niento (2000: 200) provides a definition of such programs: ‘Bilingual education programs can be defined as educational programs where two languages are used as a medium of instruction’. Bilingual education programs that were in the focus of this study consist of the dual-language programs where content in delivered in the additional language only on chosen lessons. An example of a dual-language approach is Europe is CLIL. David Marsh (2002) defined CLIL as ‘Content and language Integrated Learning, a dual-focused educational context in which an additional language is used as a medium in the teaching and learning of non language content.’ The instruction in the second language usually takes up to 50% of teaching time in the curriculum (Cummins, 2013). The main difference between CLIL and other approaches in Europe is that it has been promoted by the European Commission as a way of providing a bilingual education for all.

The second language that is introduced by schools in this study is English, which is in fact the most common language used in the dual-language curricula. For this reason, Dalton Puffer (2011: 183) calls it CEIL – Content-and-English Integrated Learning.

The European Commission’s policy European Agenda for Culture in a Globalising World, taking into consideration cultural diversity in the current world, promotes intercultural understanding, and intercultural dialogue. CLIL makes a significant contribution to that by offering many possibilities for intercultural interaction in the classroom. It is listed by the European Commission as one of the innovative approaches to improve the quality of language teaching. Effective bilingual pedagogy, performed at schools, develops students’ metacognitive skills, such as linking thinking and problem-solving strategies to particular learning situations, or clarifying aims for learning, or monitoring one’s own comprehension through self-questioning (Garcia, 2009). Therefore, the teacher’s role is to gradually maximize student learning, not just to cover material and present the content. Methods that fall under this approach generally integrate cognitive theory with communicative strategies and child-centered constructivist perspectives, where learning should involve social negotiation and integration with others in authentic contexts that are relevant to the learners (Cummins, 2006). The cognitive approach sees language as a process and what we do with language as an integral aspect of our thinking, making meaning. Accordingly, Content and Language Integrated Learning adopts an inquiry-based approach to classroom teaching and learning. It is about learning by construction, rather than learning by instruction. It focuses on language learning, learning strategies, multilingualism, multiculturalism and cooperation. Students build their content and language competences, as well as lifelong learning skills and strategies, such as dealing with the unexpected, observational skills, constructing knowledge, and so on. What is also significant, CLIL links two constructivist perspectives, Piaget’s view on how people perceive and adapt new information (the process of assimilation) and how they refer to previously learned information to make sense of it (the process of accommodation), with Vygotsky’s social constructivist perspective, which suggests that knowledge is constructed in a social context. Sociocultural theory states that people establish control and reorganize their cognitive processes during mediation as knowledge is internalized during social activity (Lightbown, Spada, 2006).

The crucial factor of a successful dual-language education program is its curriculum. The curricula cover the educational aims of the program, the time that the second language is introduced, the content, the subjects taught in L1 or L2, and the percentage of time spent on both. This study shows that the subjects usually taught in L2 are social sciences, geography, history, art, mathematics and physical education, but there is no predetermined syllabus in CLIL that any of the schools in this study follow. Nevertheless, no matter what decisions schools make in regards to the subjects taught in the additional language, the important factors here are progression and continuity (García, 2009). School involved in this study claim to make an effort to maintain these two factors by designing appropriate curricula and by conducting an ongoing evaluation of their programs. Deficiency of those two factors may lead to unsuccessful bilingual development in learners.

Effective content learning requires defined knowledge and skills together with their application through creative thinking, problem solving and cognitive challenge. This application of knowledge and thinking processes is based on Bloom’s Taxonomy of educational objectives. It defines the educational objectives into three categories: cognitive (knowing/head), affective (feeling/heart) and psychomotor (doing/hands). It is suggested that teachers should focus on all three domains in order to create a more holistic type of education. The main aim is to increase student quality talking time and reduce teacher talking time. Learners are given opportunities to develop linguistically during lessons. The focus is placed on understanding content, as it makes it easier to grasp the meaning of the word. Knowing the word and its meaning is not the same. Children learn language as a means of expressing the concepts they have acquired (Bialystok, 2001). Teachers therefore do not rely heavily on grammar, vocabulary or mechanical translation, they rely more on the situational context, brainstorming of meaning, role-playing, etc (Sousa, 2011a). During such learning process learners are encouraged to ask and answer questions, which promotes meaningful interaction. Communication is understood here, as the world knowledge through which we can create messages and make meaningful contact with one another. This meaningful contact, which involves language use and function is called ‘functional bilingualism’ by Fishman (1965). It not only entails the structure of language but also the information of who is saying what, to whom and in what circumstances (Baker, 2011). This view is reflected in the work of Krashen (1981) and Swain (1996). Krashen states that comprehensible input is crucial to language acquisition and to the development of language competence, as we acquire language by being exposed to samples of second language without consciously thinking about its form. Therefore, the input should be just above the current language competence level. Swain, on the other hand, considered that output was more important, as learners developed their language competence by expressing their understanding. In other words, the production of language made them process it more deeply. The linguistic items should not be over familiar but a little over learner’s language level, so that students won’t feel discouraged, but rather motivated by succeeding in their learning. In this way, they are bound to acquire language competence.

Language competence should be viewed as an integral part of language performance. Therefore, measuring communicative language competence cannot be done by performing classroom tests, as it is difficult to measure it in a reliable way. In fact, measuring who is or is not bilingual is such a troublesome task, that it is almost unachievable in many school scenarios. However, in every school environment teachers are obliged to assess and test their students as part of their job. It is not an easy task to assess learners in dual-language classes because we need to take into consideration language proficiency and content proficiency. Traditionally, language proficiency is associated with testing vocabulary and grammar. We can, however test it through more authentic means, such as interviews, pictures, storytelling, teacher observation, to name a few. Content proficiency, on the other hand, refers to whether students have acquired and understood the content / subject. It is important for bilingual students to be involved in the design of the assessments as well as in the assessment itself. In this way teachers and students are involved in the decision-making process that regards their own educational and learning processes, thanks to which their metacognitive awareness of how they learn can be improved. It is important that flexible assessments should be used with bilingual students. They should be given the opportunity to present their knowledge and skills concerning language, academic and social skills (Garcia, 2009). Ideally, the assessment should be ongoing, teachers should make notes about their students, the notes concern various aspects of students’ performance. This type of assessment is described as formative assessment. It is usually contrasted with the summative assessment, which happens at the end of a unit and checks the retention of content. We should use a mixture of formal and informal assessment measures, including peer- and self-assessment (Coyle, 2010). During the process of peer-assessment the content is revised again, this time by the learners themselves, which in itself improves their understanding of the topic material.

The assessment process in any form of bilingual education is rather challenging. We need to consider what to assess, content and / or language, as well as how to do it, meaning what methods we should use. The answer to the ‘language’ or ‘content’ question depends on the priority within those objectives. We would also need to focus on cognitive skills, practical skills, and learning to learn (Bentley, 2010). An ongoing approach to assessment, where teacher observes and monitors the understanding but does not make any judgment on learners, rather gives them feedback and they plan for the future, should be the norm (Coyle, 2010).

All of the above mentioned factors, most certainly, play a key role in modern education, adding to student success. The question that remains is what steps to take in order to implement a successful bilingual curriculum.

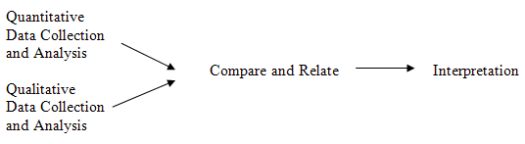

This study was grounded in the Mixed Methods Research (MMR) traditions, where a combination of quantitative (QUAN) and qualitative (QUAL) approaches was applied. The combination of the qualitative and quantitative methods can lead to a better understanding of the research problem (Cresewell & Plano Clark, 2010). Qualitative data provide a detailed understanding of a problem, while quantitative data provide a more general understanding of a problem (Cresewell & Plano Clark, 2010). Integrating methodological approaches enhances the research design, as the strengths of one approach counterbalance the weaknesses of the other (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011). MMR is the type of research design in which QUAN and QUAL approaches are used in the types of questions, research methods, data collection, and analysis procedures. Therefore, deductive and inductive logic of inquiry should be applied and the research questions should be of primary importance.

In this study both strands intentionally interact with one another during the course of the investigation. This convergent parallel design was implemented as there was a need for a more thorough understanding of the topic.

Figure 1. The convergent parallel design

In this study equal priority was given to the two methods. The timing of the phases was concurrent. Both QUAL and QUAN methods were implemented during each phase of the study. The point of interface occurred during the design phase and the research design was fixed. The use of QUAL and QUAN methods was planned at the start of the study and later implemented. The results of the research were combined and interpreted together. However, they were case oriented. The purpose of such a design is to overcome the weaknesses and strengths of quantitative methods, such as large sample sizes or generalization, with those of qualitative ones, such as small samples and details (Patton, 1990).

The general objective of this study was to identify the measures taken when implementing the dual-language programs, and to find ways of describing and comparing them.

The specific objectives are:

- To identify what type of curricula are implemented and how successful they are.

- To describe present education practices in each of the schools.

Schools that wish to incorporate a bilingual education program should pursue the following goals for bilingual learners (Brisk, 2010: 97):

- Language proficiency to academic grade level.

- Sociocultural integration to their ethnic community and the society at large.

- Academic achievement, as defined by the school, for all students.

Other aspects of bilingual education which should be taken into consideration in order to have a successful bilingual curriculum are pedagogies, individual learners, communities, and the balance between all of them (García, 2009).

All bilingual students should participate in a comprehensive and effective curriculum, meaning that:

- All content areas are covered.

- Content, language, and culture are integrated.

- Thinking and study skills are explicitly taught.

- Materials should be varied, high quality, interesting, and provided in the native language as well as English.

- Content and language assessment should be ongoing, authentic, and fair.

When planning to implement a bilingual curriculum, language teaching, content, and literacy should be integrated. Brisk (2010) states that the mission of schools is to educate students so that they have choices when they graduate. Language policies adopted by a school should be followed by all teachers in order to provide consistent language development.

Currently many of the education programs in the world are either designed for social elites or for disadvantaged immigrants who are placed in transitional bilingual education programs. Hence, the aim of this study was to include public schools that have a few years of experience in operating their dual-language program (Trento, Italy) or only recently started the process of its implementation (Badajoz, Spain; Wołów, Poland). The schools that participated in the study were chosen with reference to the specific context in which they were situated. The case selection was determined by the research purpose, and theoretical context, but also by other restrictions such as accessibility, resources, and the time available (Rowley, 2002). The study presents data concerning all grades of the primary schools involved.

All of the above schools declare adopting dual-language curricula and English as the language of L2 instruction. In Trento, Italy, bilingual classes start in year 1 and involve 20 hours out of 30, while eight subjects are entirely taught in L2; only Italian, history, and religion are in L1. In Badajoz, Spain, there are 3 hours of English (ESL) a week and 1 hour of Art in English and 4 hours of Science. The school follows a Spanish curriculum and it might adapt an international program in the future. As for Wołów, Poland, there is no set proportion between L1 and L2 – parts of lessons are taught in L2, usually mathematics, biology or PE. The school declares that it increases the time spent on L2 as pupils’ L2 competence improves.

This study shows significant differences between the curricula in all of the schools. Some schools have no bilingual curriculum outcomes prescribed (Wołów, Poland), others use a curriculum designed and accredited by a government body (Trento, Italy; Badajoz, Spain). Much depends on the type of school setting. Of course, there are some general curricular guidelines in Europe on how to implement CLIL, for example, www.clilcompendium.com or www.clilconsortium.jyu.fi to name two – but they are very broad and need to be adapted to each school’s individual context. This shows the necessity for local councils or governments to produce appropriate guidelines to be followed by schools willing to introduce bilingual education programs. In Poland there are no guidelines as such. Trento is an example of good practice. It is located in a region with an independent education system, where schools follow the PAT curriculum, which is an adaptation of the national curriculum, and reflects this region’s political, historical, and geographical reality. In Spain, there have been numerous projects conducted in respect to CLIL implementation that provide guidelines for schools (Escobar Urmeneta, 2010; the British Council and the Ministry of Education, 2010). Moreover, there are many uncertainties expressed by schools starting to implement bilingual education programs. Some schools (for example, Wołów, Poland) have numerous doubts about the subjects that need to be taught in L2, the number of hours spent on L2 in a school week, and which extra-curricular activities should be pursued, as there are no guidelines available. All of the schools promote their programs as dual-language, where English is used as a medium of instruction. However, during the school visits and interviews with teachers, the language present in the CLIL lessons was predominantly students’ L1 (Badajoz) or English in a form of a lecture (Wołów), with no or little use of situational context, brainstorming meaning, or meaningful interaction between students, which may indicate the lack of teachers’ competence or prior training.

Therefore, apart from the curriculum itself, it is the teachers’ qualifications that need to be taken into consideration when implementing a bilingual education program as well. It seems to be a challenge for the schools to find qualified teachers, especially that there are no particular requirements as for the teachers teaching in bilingual schools. Teachers who are subject teachers and would like to teach it through English are required to have a certificate relating to language proficiency, usually the Cambridge English First Certificate (FCE). However, sometimes, as this study shows, this is not the case as schools lack teachers to conduct lessons in dual-language classes and simply involve subject teachers who have a good command of English (Wołów, Poland; Trento, Italy; Badajoz, Spain). Nevertheless, it is not only teachers’ English language competence that needs attention, but also the classroom language in general (Pena, Porto, 2008). Some of the teachers in this study (Wołów, Poland; Badajoz, Spain) admitted that teaching a subject through a second language is a great challenge, especially giving instructions in L2 and thinking of language aims for the lessons.

Currently, a tendency that can be observed across Europe is for the subject teachers to attend English language courses in order to improve their English language skills. However, as recorded in this study, it is not only the language skills need improvement, but also the methodology of English language teaching and the understanding of dual-language education as a whole. This study indicates the need for subject teachers’ to attend further training. This demand is especially strong among those teachers who were told to teach their subject in L2 without prior training (Wołów, Poland) or with little training (Badajoz, Spain). It is hard to become competent professionals without training (Larrea, Raigón and Gómez, 2012: 12).

This study shows that teachers who have some previous theoretical training, know the theory of dual-language curriculum and teaching well, but do not always apply it in their lessons. It seems that this type of training is beneficial in terms of understanding of theory but not in changing teachers’ teaching habits in terms of lesson planning and conducting the lessons. In view of the above, it can be stated that bilingual schools need a lot of external support in terms of in-house or school-based training, designing materials, planning lessons, conducting assessment, as well as peer and external lesson observations and evaluation. In schools that have just started applying their bilingual education programs there is a greater need for teacher training than in those which have been established for a longer period of time where teachers are more experienced. Therefore, we can say that there is an immense need for institutional support. There should be more support provided for the schools wishing to implement a bilingual curriculum in the form of practical publications/guides, as well as personal support from teacher trainers.

Baker, C. (2011) The Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 5th edition, Bristol, UK, Multilingual Matters.

Bentley, K.. (2010) The KTK Teaching Knowledge Test Course. CLIL Module. Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bialystok, E. (2001) Bilingualism in Development. Language, Literacy and Cognition. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Brisk, E. (2010). Bilingual Education. From Compensatory to Quality Schooling. Routledge, London and New York.

Cazabon, M., Lambert, W. E., Hall, G. (1993). Two-way bilingual education: A progress report on the Amigos Program, Research Report No. 7, The National Center for Research on Cultural Diversity and Second Language Learning, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA.

Coyle, D. (2007) Content and language integrated learning: Motivating Learners and Teachers. In The CLIL Teachers Toolkit: a classroom guide. Nottingham: The University of Nottingham.

Coyle, D., Hood, P., Marsh, D. (2010) CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cresewell, J. W., Plano Clark, V. L. (2010). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 2nd edition. Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W., Klassen, A. C., Plano Clark, V. L., Smith, K. C. for the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. (2011, August). Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health. Retrieved from: http://obssr.od.nih.gov/mixed_methods_research accessed 5th December, 2013.

Cummins, J. (2006) Language, power and pedagogy. Bilingual children in the crossfire. Great Britain, Cambarian printers ltd.

Cummins, J. (2013). Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL): Research and its

classroom implications. In Padres y Maestros, Vol. 349: 6-10.

Dalton-Puffer, C. (2011). Content and language integrated learning: from practice to principles. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 31, 182-204.

Garcia, O. (2009) Bilingual Education in the 21st Century. A Global Perspective. West Sussex, Wiley-Blackwell.

Genesee, F., Geva, E., Dressler, C., Kamil, M. (2006). Synthesis: Cross-linguistic relationships, Chapter 6. In D. August & T. Shanahan (Eds), Developing literacy in second language learners. Report of the National Literacy Panel on Minority-Language Children and Youth, 153-174. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Howard, J. S., Sparkman, C. R., Cohen, H. G., Green, G., Stanislaw, H. (2005). A comparison of intensive behavior analytic and eclectic treatments for young children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 26: 359 – 383.

Krashen, S. (2004). The Power of reading. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Larrea Espinar, A.M., Raigón Rodríguez, A.R. & Gómez Parra, M.E. (2012). ICT for Intercultural Competence Development. Píxel Bit: Revista de Medios y Educación. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla, 40: 115-124. Retrieved from: www.redalyc.org/pdf/368/36823229009.pdf accessed 11th February, 2014

Lightbown, P., Spada, N. (2006) ‘How languages are learned.’ Third edition, Oxford, OUP

Lindholm-Leary, K. J. (2001). Dual Language Education. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Mackenzie, A. (2012) How should CLIL work in practice? Retrieved from: www.onestopenglish.com

Marsh, D. 2002. Content and Language Integrated Learning: The European Dimension - Actions, Trends and Foresight Potential.

http://europa.eu.int/comm/education/languages/index.html

Menegale, M. (2011) ‘Teacher questioning in CLIL lessons: how to enhance teacher-student interaction.’ In: Educacion plurilingue: experiences, research and politics. Moor, Escobar, Evnitskaya, Patiño, (eds).

Nieto, S. (2000). Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education. New York: Longman.

Patton, M. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Rowley, J. (2002). Information marketing in a digital world. Library Hi-Tech, 20 (3): 352-358.

Sousa, D. (2011a) How the ELL Brain Learns. United States of America, California, CORWIN.

Sousa, D., Tomlison C. (2011) Differentiation and the brain. How Neuroscience Supports the Learner-Friendly Classroom. Bloomington, Solution Tree Press.

Vaid, J. (2000) New approaches to conceptual representations in bilingual memory: the case for studying humor interpretation. In Bilingualism: Language & cognition, 3: 28-30.’

Please check the Methodology & Language for Kindergarten Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|