An Investigation of Effects of Role-play on Students’ Speaking Skill in an EFL Context

Tham My Duong, Vietnam

Tham My Duong has been teaching English at Nong Lam University, Vietnam for over nine years. She earned a TESOL Master’s degree at University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vietnam. She has currently been a Ph.D. candidate at Suranaree University of Technology, Thailand. Her research interests include learner autonomy, TESOL methodology, task-based learning and content-based instruction. Email: duongmythamav@yahoo.com

Menu

Introduction

Literature review

Methodology

Results and discussion

Conclusions and recommendations

References

People of all ages in the world learn English with various reasons. Harmer (1998) indicates that English is learned as a compulsory subject at school and for other specific purposes such as business, tourism, or banking. In Vietnam, students first learn English as it is a required subject at school. They then need English for communication, e.g., they need English for seeking a good job, travelling, entertaining (reading books or watching movies) and studying overseas. However, Vietnamese students often find it difficult to communicate in English. One of the major reasons affecting students’ oral communication is that the chance of using the target language is not much. Inevitably, English speaking environment for EFL students in Vietnam is mainly classroom as Dang Thi Huong (as cited in Vo, 2005) found out, “even learners majoring in English at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Ho Chi Minh City used 80% English and 20% Vietnamese inside the classroom while they likely to use only 20% or 30% English and 80% or 70% Vietnamese outside the classroom” (p. 2). Besides, students have few opportunities to participate in English speaking clubs, English song contests, or international events such as the program of exchanging students with foreign universities, study tour, etc.

Nong Lam University (NLU) (formerly the University of Agriculture and Forestry) of Ho Chi Minh City was founded in 1955. It consists of 12 faculties with 69 departments and 5 independent departments. In 2001, the Faculty of Foreign Languages (FFL) was officially founded because NLU has aimed at transforming into a comprehensive university with a broad range of educational programmes. FFL is quite young, but NLU has the Center for Foreign Studies (CFS), which was established in 1990. It is known as one of the popular English language centres in Ho Chi Minh City as well as in Vietnam. Therefore, FFL could inherit qualified teaching staff from CFS because most of the teachers at FFL have been teaching at CFS for a long time. The Faculty comprises departments of Language Practice, Foreign Literature, Translation and Interpretation, TESOL Methodology, Linguistics, ESP, Management, and French. The Bachelor of Art training programme lasts four academic years. There are three speaking courses which are taught in the first three terms. All teachers in charge of speaking courses at FFL have M.A degrees and at least nine-year experience of teaching spoken English.

In order to study at FFL, students have to pass the university entrance exams which consist of three subjects: Mathematics, Literature, and English. Therefore, the expected level of English of first-year English majors is pre-intermediate. However, the majority of students have difficulties with English speaking and listening skills. Nowadays, students can get more and more opportunities to have direct interaction with foreigners, mainly English native speakers; therefore, they often use English for communication. To meet students’ needs, the faculty has paid more attention to the communicative approach in order to make students use the target language naturally and confidently in different social contexts. Communicative activities such as role-plays, problem-solving tasks, or games are used in the classroom so as to encourage students’ participation in speaking activities. Nevertheless, role-play has not been commonly used in an English speaking class at FFL-NLU. In this study, hence, the researcher would like to investigate the effect of role-play on first-year English majors’ English speaking skill at NLU. The aims of this study are to investigate the problems of first-year English majors at NLU-HCMC in learning English speaking skill and to identify effects of role-play in teaching and learning English speaking skill.

The nature of speaking

Burns and Joyce (1997) define that speaking is an interactive process of constructing meaning that involves producing, receiving and processing information. Celce-Murcia and Olshtain (2000) claim that speaking can be considered the most difficult skill to acquire because it requires the command of both listening comprehension and speech production sub-skills in unplanned situations. On the other hand, it can be viewed as the easiest skill since one can use nonverbal communication, repetition, and various other strategies to produce comprehensible utterances.

Role-play

Role-play is “drama-like classroom activities in which students take the roles of different participants in a situation and act out what might typically happen in that situation” (Richards et al., 1993, p. 318). According to Harmer (1998), role-plays stimulate the real world in the same way, but students are given different roles. Students are told who they are and what they think about a certain subject. They have to talk and act with their new characters. While Richards et al. (1993) and Harmer (1998) define role-play as a term, Ladousse (1992) characterizes role-play as two single words as follows.

When students assume a “role”, they play a part (in either their own or somebody else’s) a specific situation. “Play” means that the role is taken on in a safe environment in which students are as inventive and playful as possible.

(p. 5)

Meanwhile, Thornbury (2005) thinks that role-play involves the adoption of another “persona” (p. 98) when students play a role. For example, students pretend to be an employer interviewing a job applicant or a customer complaining about a company’s products.

Regarding the advantages of role-play, Dangerfield (1991) believes that role-play is one method of maximising students’ talking time, ensuring that students get an optimum level of practice during their limited class time. Furthermore, role-play gives students opportunities to improve communicative competence and creativity. Klippel (1991) claims that “role-plays improve the students’ oral performance generally” (p. 122). Besides helping students enhance their oral skills, Sasse (2001) believes that role-play might unlock creative doors. Last but not least, role-play is one of the communicative techniques “which develops fluency in language students, which promotes interaction in the classroom, and which increases motivation” (Ladousse, 1992, p. 7).

In brief, there have been various definitions of role-play, yet they share the same idea that role-play is a communicative technique in which students are supposed to act with new characters.

Factors affecting EFL learners’ speaking

In order to investigate how EFL learners’ speaking ability is affected, it is necessary to consider the factors of age, gender, and affection.

Age is considered one of the most debated issues in language teaching theory because it determines the success or failure of foreign language learning. According to Scarcella & Oxford (1992), adult learners seem not to have the same innate language-specific endowment or propensity as children for acquiring fluency and naturalness in spoken language. Concerning affective factors, younger children are less frightened because they are less aware of language forms and the possibility of making mistakes in those forms, whereas adults’ attempts to speak in the foreign language are often fraught with embarrassment (Brown, 2000, p. 65).

In order to prove that one of the major pragmatic factors affecting the acquisition of communicative competence in virtually every language is the effect of one’s gender on both production and reception of language, Romaine (1994) discovers that girls speak more politely, whereas boys speak roughly and use more slang and swear words. When asking about some boys’ behaviours towards their peers, they say that they have to talk rudely with other boys in order not to be ridiculed. During adolescence under the influence of peer pressure, boys shift towards more non-standard speech, while girls retain their more standard speech because they think that they have to be careful not to go too far or people will judge them negatively. Goddard and Patterson (2000, p. 92) also believe that “While female behavior is often constructed and interpreted in particular ways, men have freedom to define themselves in any way they want.”

With regard to affection, while Thornbury (2005) states that affective factors include feelings towards the topic and/or the participants and self-consciousness, Brown (2000) emphasises:

The affective domain is the emotional side of human behavior, and it may be juxtaposed to the cognitive side. The development of affective states or feeling involves a variety of personality factors, feeling both about ourselves and about others with whom we come into contact.

(p. 143)

According to Brown (2000), the affective factors which are related to second language or foreign language learning are motivation and attitude, anxiety, etc. These items are called “psychological characteristics” in which motivation and attitudes are paid most attention because various studies have found that they are very strongly related to achievement in language learning (Gardner & Lambert, 1972). Littlewood (1991a) also states, “the development of communicative skills can only take place if learners have motivation and opportunity to express their own identity…” (p. 93). In fact, Brown (2000) determines that it is easy to assume that success in any task is due simply to the fact that someone is “motivated”. Regarding anxiety, the construct of anxiety plays an important role in second language acquisition. According to Littlewood (1991b), it is easy for a foreign language classroom to create anxiety. There are two types of anxiety affecting the process: debilitative (or harmful) and facilitative (or helpful). The feeling of nervousness is often a sign of facilitative anxiety, a symptom of just enough tension to get the job done. Brown (2000) concludes that “both too much and too little anxiety may hinder the process of successful second language learning” (p. 152).

Research questions

(1) What are the problems first-year English majors at FFL-NLU face in English speaking learning?

(2) What factors contributing to the support and resistance to the use of role-play in a speaking course?

(3) Does role-play improve the students’ English speaking skill after the use of role-play in the speaking course? If so, how?

Research design

Qualitative and quantitative methods were employed in this study. Each research method has its own characteristics. Qualitative research uses a variety of means such as observations, tape-recording, questionnaires, interviews, case histories, field notes, and so on to collect data. The ultimate goal of qualitative is to discover phenomena and to understand those phenomena from the perspective of participants in the activity (Seliger & Shohamy, 1997). Quantitative research is used to process the data of the questionnaires since it can describe phenomena in numbers and measures instead of words (Johnson & Christensen, 2012).

Characteristics of subjects

There were two groups of subjects in the study: Vietnamese teachers of English and first-year English majors. The first group consisted of ten Vietnamese teachers of English at Nong Lam University. Among the respondents, there were two senior lectures. Four of the respondents were male and six were female. There were five respondents who were in the age range from twenty to thirty, two were in the age range from thirty-one to forty and three were in the age range from forty-one to forty-nine. The majority of the teachers have spent at least nine years in teaching English to English majors at this university. All of the respondents got M.A. degrees. The second group including sixty-six first-year English majors at Nong Lam University was equally divided into the control group and the experimental group, accordingly named group A and group B. Of thirty-three respondents of group B, there were five males (15.2%) and twenty-eight females (84.8%). Most of them were nearly of the same age: twenty-five respondents were eighteen years old (75.8%), eight were nineteen years old (24.2%). In group A, there were seven males (21.2%) and twenty-six females (78.8%). The age range in this group was a little more different than in the experimental group: 2 respondents were twenty years old (6.1%); four were nineteen years old (12.1%); and twenty-seven were eighteen years old (81.8%). They all have been learning English for over seven years.

The experiment

The English speaking course lasted thirty periods (one period is equal to 45-minute class contact) taught in fifteen weeks. The textbook of this course entitled “Let’s Talk 2” was used for both the experimental and control groups. The researcher is in charge of both the group. The speaking course in the control group was material-based, whereas role-plays introduced in the experimental group were based on the activities suggested in the main textbook Because of time limit, only the units with familiar topics were taught in class. With the aim to help students use spoken English structures accurately, the teacher introduced useful functional language for each unit.

Data collection

• Questionnaire for teachers

The closed-ended questionnaire for teachers was written in English because they are Vietnamese teachers of English included two parts. Part I of the questionnaire consisting of first five questions requested teachers to provide personal information (about age range, gender, qualifications, and years of experience in teaching English). Part II consisted of thirteen questions to elicit teachers’ perceptions of the students’ current English speaking problems and the effect of role-play on enhancing their English speaking skill.

The questionnaire was delivered to the first group of subjects who have been working at FFL-NLU. All of them were willing to complete the questionnaires which were returned to me immediately.

• Questionnaire for students

Unlike the questionnaire for teachers, the closed-ended questionnaire for students was written in Vietnamese to ensure that the subjects’ understanding of the questionnaire was not affected by their English proficiency, and the questionnaire was designed in the multiple-choice format so that students could answer the questions easily. The questionnaire also consisted of two parts. In part I, students were asked to provide personal information (about age, gender, and years of learning English) in the first three questions. In Part II, there were twelve questions which investigated students’ opinions about current English speaking problems and the effect of role-play.

The questionnaire was delivered to the student participants at the end of the speaking course. They could bring them home and submit them to the class monitor who collected and returned them to me on the next day.

• Tests

A diagnostic test and an achievement test were carried out in two groups of student subjects: experimental group and control group. The diagnostic test was carried out in both the control and the experimental groups at the beginning of the training course to ensure that students’ English speaking ability in both the groups was the same. The achievement test aimed at measuring students’ English speaking achievement after role-playing was introduced in the experimental group.

As far as speaking assessment is concerned, the criteria to assess students’ speaking ability included four categories: fluency, accuracy (grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation), interactive communication, and task completion.

The diagnostic and achievement tests were conducted in both the experimental group and the control group at the first and sixteenth weeks. Examiners graded each student while students were role-playing in pair.

Data analysis

The data obtained from the questionnaire and tests were quantitatively analyzed. Specifically, descriptive statistics (i.e., frequencies/percentages) were employed to process data collected from the questionnaire. On the other hand, paired samples t-test was used to compare the diagnostic test and the achievement test within the two groups to examine whether or not there were significant differences.

Teachers’ responses to the questionnaire

When answering the question which examined students’ weaknesses in English speaking, nine teachers (90%) identified poor pronunciation which made students unable to speak English as the biggest problem. 60% of them recognized that shyness prevented students from communicating in the target language. Furthermore, teachers said that poor vocabulary (40%) and poor grammar (20%) were also students’ problems in English speaking. That is why students often used mother tongue to express their ideas. In addition to psychological factors such as shyness, anxiety, or fear of making mistakes and being laughed at, 40% of the teachers paid attention to students’ “lack of ideas” in communication when teaching English speaking skill.

In respect of the benefits of role-play in learning English speaking, 80% of the teachers agreed that role-play was beneficial to students because it provided real life situations. This encouraged students to express themselves more easily. 70% of the teachers admitted that their students felt excited with role-play. Similarly, seven out of ten teachers (70%) agreed that students had many chances to practise English speaking thanks to role-play. Half of the teachers thought that role-play might increase students’ interaction as Ladousse (1992) states that role-play is one of the communicative techniques which promote interaction in the classroom.

Teachers were expected to explain the reasons why they did not like to use role-play. The responses were quite predictable. Noise was the most concerned reason which discouraged teachers from using role-play in their speaking classes; therefore, 70% of the teachers chose this. Another reason many teachers (60%) were afraid of role-play was that it was time-consuming. Moreover, 50% of them stated that they found it difficult to make the content of role-plays interesting since role-play is almost not available in the textbook. As a result, they spent a lot of time in searching and adapting situations from many sources of teaching materials. Three teachers (30%) found that role-play was more difficult than the speaking tasks in the textbook since students themselves had to think what to say with a few clues in role-plays.

Teachers were required to give their ideas about the effect of role-play on students’ speaking skill. Most of the teachers recognized the benefits of role-play to their students’ speaking ability. Particularly, they perceived that their students spoke English more naturally (70%) and more confidently (70%). Moreover, 60% of the teachers realised that students spoke English more smoothly after the application of role-play. According to Ladousse (1992), language teachers all want students to be both fluent and accurate in the way they speak. However, while a large number of teachers admitted that role-play could improve students’ fluency in speaking English, a small proportion of teachers (20%) believed that students could use the language exactly. To sum up, all teachers to some extent identified the effects of role-play on developing students’ speaking ability.

Students’ responses to the questionnaire

Concerning the problems of first-year English majors at Nong Lam University in learning English speaking, the results showed that participants’ lack of vocabulary was the main weakness which limited their interaction (93.9%). 78.8% of them were afraid of English pronunciation. In addition to poor grammar (51.5%), psychological factors such as shyness or anxiety really caused some problems for students in speaking English (57.6%) as Shumin (1997) observes, speaking a foreign language in public, especially with native speakers, is often anxiety-provoking.

Dealing with the questions relating to benefits of role-play, most of the participants (84.8%) agreed with the statement that role-play provided real life situations for students. It can be inferred that through real-life situations, the participants can share their experiences with each other, which encourages them to use the language more naturally. 75.8% of the participants felt excited with role-play because role-play was a “fun activity” for most students (Ladousse, 1992). Obviously, interesting communicative tasks may increase motivation. This might change participants’ attitudes towards the use of role-play in teaching English speaking skill. In relation to students’ talking time, Lewis and Hill (1985) suggest that the teacher should use pair work or group work to increase participants’ talking time. Based on Lewis and Hill’s (1985) suggestion, participants were asked about chances in practising English speaking skill with role-play. Thus, up to 63.6% of the participants reported that they had opportunities to use spoken English after using role-play. The finding leads to a potential conclusion that role-play may increase participants’ talking time. Increasing students’ talking time is a big difference between the communicative approach and the traditional method as Lewis and Hill (1985) emphasize, “effective language teaching means giving the students a chance to speak” (p. 45). One more benefit of role-play that was revealed by more than half of the students (51.5%) was that they could combine the language with nonverbal communication in order to improve communicative competence. For example, they sometimes could not understand some utterances of native speakers or foreigners, but thanks to body language, eye contact or gestures, they could guess the meaning of the utterances.

With regard to the factors that made role-play not interesting, 66.7% of the participants claimed that the teacher could not assist them to correct all mistakes in pronunciation, grammar, or vocabulary. Since students often worried about their mistakes, they requested teachers to correct any mistakes. The teacher could correct their mistakes while joining pair or group work activities. However, she could not do so for all students in a limited time. Making noise was one of the participants’ concerns. 54.5% of them said that practising spoken English with role-play might make the class noisy and disordered. Obviously, group work in a large class size would be noisy, and this was natural. Sometimes noise was likely to occur when the participants were confused and did not know what to do. Besides, fifteen out of thirty-three participants (45.5%) found that role-play was more difficult than speaking tasks in the textbook. Because role-play was unfamiliar to students, teachers had to ensure that students understand what was on the role cards before starting. Certainly, teachers should not use a role-play that is too difficult until students are used to this activity. Instead, Ladoussse (1992) suggests that teachers can start with pair work and easy information-gap role-plays. The boring content of role-plays was also one of the factors that would decrease their interest in learning speaking skill with role-play. There were seven students (21.2%) who did not like the content of role-plays.

The results collected from students’ responses to whether role-play helped improve their speaking skill were quite optimistic. Only two out of 33 participants (6.1%) did not know whether role-play helped them improve their English speaking ability or not. The rest of participants (93.9%) stated that their speaking skill was improved thanks to role-play. Particularly, the number of participants recognized that role-play might help them speak English naturally was the biggest (66.7%). A large number of them (63.6%) felt very confident while practising English speaking with role-play; 39.4% agreed that it also helped them speak English more fluently; and 30.3% of the students thought that it assisted them to use the language at the right time and at the right place.

In short, the teacher’s and students’ responses to the questionnaire were somehow different, but they basically believed that role-play could help enhance the students’ speaking ability.

Test scores

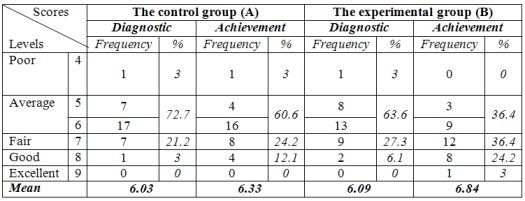

In order to find out the effect of role-play on English speaking skill of participants in the experimental group, the diagnostic and achievement tests for both the groups: group A (the control group) and group B (the experimental group) were designed and presented in the following table.

Table 1. Results of the diagnostic and achievement tests

The results of the diagnostic test indicated that the mean score of group B (X̅=6.09) was nearly the same as that of group A (X̅=6.03). In group B, two participants (6.1%) got good scores, the number of participants who got fair was nine (27.3%), many participants (63.6%) got average scores, and there was one participant whose score was poor (3%). Similarly, most of the participants in group A got average scores (72.7%), and 24.2% of the participants got fair and good scores.

The difference between the two groups was shown more obviously in the achievement test. In group A, about two-thirds of the participants (60.6%) were ranked at average level; few participants (12.1%) were ranked at good level; and there was one student (3%) who got poor score. Meanwhile, all of the participants in group B got at least score 5. There were twenty out of thirty-three participants (60.6%) ranked at fair and good levels. Especially, one student (3%) got excellent score, and no participants had poor scores. The mean score of group B (X̅=6.84) which was higher than group A’s (X̅=6.33) once again indicated the difference between the two groups.

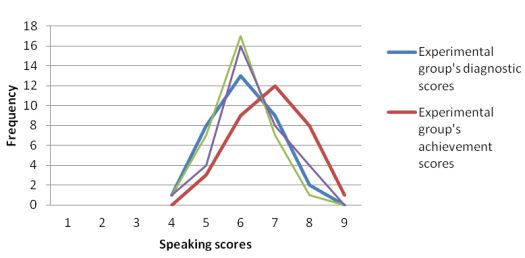

The frequency distribution of the diagnostic and achievement scores was presented in the following histogram. The histogram stated that group B’s achievement scores were better than group A’s. The red line standing for group B’s achievement scores moved to the right of the histogram in which high scores were displayed while the other lines were on the left.

Figure 1. Speaking scores frequency distribution

According to Figure 1 and Table 5, there was no significant difference between diagnostic and achievement tests of group A (P=0.135>.05). It means that the diagnostic scores of group A were not considerably different from the achievement ones. The majority of participants in both the tests were at average level (scores 5 & 6). In contrast, the participants of group B made much more progress in their speaking skill in the achievement test than those in the diagnostic test (P=0.002<.05). In fact, one student whose score was poor (score 4) in the diagnostic test got score 5 in the achievement test, and they mostly got score 7 (36.4%) and score 8 (24.2%). In addition, the improvement was easily realised when a student achieved score 9.

To sum up, there was a very small gap between the two groups at the beginning of the speaking course. However, the sharp difference between them was really explored when there were achievement scores. This result was one of the important evidences to state that role-play could help improve participants’ speaking skill to some extent.

Conclusions

With the advantages of role-play analysed from teachers’ and students’ responses to the survey questionnaires and the analysis of students’ test scores, the study explored the positive effect of role-play on the improvement of students’ speaking ability to some extent. Firstly, role-play helped students reduce psychological burdens. The majority of students admitted that they felt more confident after using role-play because they had many opportunities to practise spoken English in pairs or groups and sometimes spoke English in front of the class. Secondly, students could interact with one another naturally because with real life situations, they might use functional language and strategies to maintain and develop conversations and combine the language with nonverbal communication to express their opinions. Finally, role-play developed students’ fluency since students could express their ideas in unstructured conversational situations.

Recommendations

• To students

Students should try to speak English as much as possible since practice can be undoubtedly very useful (Lewis & Hill, 1985). They should attend English speaking clubs or international events if possible.

Students should not be afraid of making mistakes. Practically, only a few students regard mistakes as a natural part of leaning while the majority of them feel ashamed of making mistakes. If they do not worry much about mistakes, they will feel more comfortable and confident to speak English.

• To teachers

Language teachers need to determine that developing strategies for maximising the amount of students’ talking time is necessary. Teachers should let dominant students and shy students work together so that they have opportunities to share and learn from each other.

Furthermore, in an English speaking class, teachers tend to encourage students not to use mother tongue. Therefore, teachers should not introduce too difficult situations, otherwise students have to use mother tongue to interact.

• To administrators

Besides the above suggestions, it is useful for the administrators of FFL to consider the following. Equipping classrooms with better conditions is needed. Classrooms should be enlarged and equipped with modern facilities such as overhead projectors, good cassettes and tapes, VCRs, and microphones. Besides, comfortable movable desks are necessary for a speaking class.

English speaking environment should be created. If possible foreign teachers who are from English-speaking countries should be invited to teach communication skills. Besides maintaining English speaking clubs, English song or play contests and English quizzes should be held frequently so that students can learn English in a non-threatening environment.

Brown, H. D. (2000). Principles of Language Learning and Teaching. New York: Long man.

Burns, A., & Joyce, H. (1997). Focus on Speaking. Sydney: National Center for English Language Teaching and Research.

Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and Motivation in Second Language Learning. Rowley, Mass: Newbury House.

Goddard, A., & Patterson, L.M. (2000). Language and Gender. Great Britain: International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall.

Harmer, J. (1998). How to Teach English. UK: Longman.

Jones, L. (2002). Let’s Talk 2. UK: CUP.

Klippel, F. (1991). Keep Talking: Communicative Fluency Activities for Language Teaching. Cambridge: CUP.

Krashen, S. D. (1987). Principle and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. UK: Prentice Hall International.

Ladousse, G. P. (1992). Role play. Oxford: OUP.

Lewis, M., & Hill, J. (1985). Practical Techniques for Language Teaching. Language Teaching Publications.

Littlewood, W. (1991a). Communicative Language Teaching. Cambridge: CUP.

Littlewood, W. (1991b). Foreign and Second Language Learning. Cambridge: CUP.

Richards, J. C. & Platt, J., & Platt, H. (1993). Dictionary of Language Teaching & Applied Linguistics. London: Longman.

Romaine, S. (1994). Language in Society. New York: OUP.

Sasse, M. (2001). Role-playing in the Second Language Classroom. Teacher’s Edition, 1, 4-8

Scarcella, R. C., & Oxford, R. L. (1992). The Tapestry of Language Learning. Boston, M.A: Heinle & Heile Publishers.

Seliger, H.W., & Shohamy, E. (1997). Second Language Research Methods. New York: OUP.

Shumin, K. (1997). Factors to Consider: Developing Adult EFL Students’ Speaking Abilities. English Teaching Forum, 35 (3), 8. Retrieved from

http://dosfan.lib.uic.edu/usia/E-USIA/forum/vols/vol35/no3/p8.htm

Thornbury, S. (2005). How to Teach Speaking. New York: Longman.

Vo, T. T. K. (2004). Teacher’s Edition. Hanoi: English Language Institute.

Vo, O. T. P. (2005). How to Improve the Teaching and Learning of Spoken English to Pre-intermediate English Learners at AFU Foreign Language Centre. HCMC: USSH.\

Please check the Methodology & Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|