Visualising Grammar and Literacy in Young Language Learning (Or: How to Build a Castle from Building Bricks)

Mija Selič, Slovenia

Mija Selič is a teacher, teacher trainer and executive assistant to the CEO at the C00lSch00l private language school. She is an innovator in finding new ways of teaching and in developing teaching materials for very young language learners. She has a master’s degree in primary teaching and a degree in English. She also holds a certificate in convergent pedagogy. E-mail: mija.selic@gmail.com, web site:

www.c00lsch00l.eu,

blog: http://c00lsch00l.blogspot.si/

Menu

Introduction

Highlighting the main points of effective early language learning

About building bricks

Words (building bricks) as part of a sentence/story/context (the building)

Step one: Visual reading

Step two: Visual summary of the picture books

Step three: Creating a Word Web

Step four: Visual sentence making

To sum up

References

A detailed approach to effective foreign language learning for young children has already been described in the HLT magazine (Selič, M., Making Early Language Learning Effective, October 2014). I will, however, highlight the main points in order to establish a basis for the further development and upgrading of the approach, which leads to visual language learning.

The child’s mind sees the world globally connected in all aspects. The adult’s world, on the other hand, is analytical (Marjanovič Umek, 2004). One aspect of the adult’s manifestation is the world divided into different school subjects. Unfortunately, this is something a child cannot easily comprehend. It is therefore important for primary school teachers to understand the concept of how the child sees the world. In order to make any learning effective, children need to have a context, preferably topic related, in which the child’s world is connected.

Secondly, in order for the learning process to be effective, it has to be presented as an enjoyable, relaxing, interesting and challenging event. For a child, I believe, any game-like activity can count.

And what does ‘a game-like activity’ actually mean?

If I try to put myself in a child’s shoes, one version of a game would certainly be an activity where there is a challenge accompanied with a context. The challenge can be manifested in different ways, such as scoring points or achieving a certain position/level/task in a limited available time. This is even better if there can be one or (preferably) more winners.

In relation to early language learning, up to the age of 8 or 9, all of the activities should have a context, should be wrapped in stories or turned into games, and should thus achieve specific language aims. In my experience, any textbook, coursebook or workbook kills the possibility of an effective game-like organised programme. Additionally, their use is the main reason for the severe decline in children’s creativity (Kyung Hee Kim, 2011).

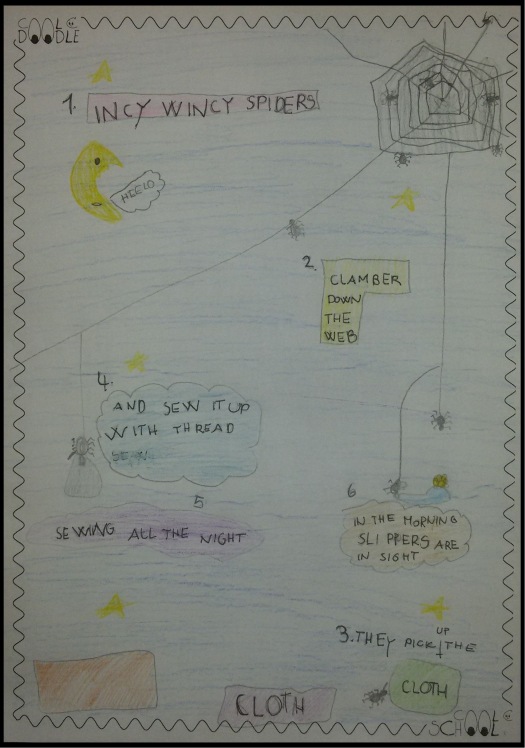

In the described approach, textbooks, workbooks and coursebooks are substituted with unique C00lSch00l teaching aids. The first is the Picture Dictionary. It is a tool made of two fabric houses, with the windows turned into pockets in which flashcards (the CoolTool) are kept alphabetically or thematically. The second tool is the CoolDoodle, black and white partly drawn pictures that children complete as they like, thus also enhancing their imagination and creativity. Once the artwork is completed, the children can add words: collocations, phrases, chunks of words, sentences, etc. An example of an individually completed doodle can be seen in Illustration 1.

Illustration 1: An example of a CoolDoodle for the song Incy Wincy Spiders (age 8)

I am certain that everyone knows the famous LEGO bricks. Not only children, but also adults. I also believe we can all agree that they are a unique tool that opens the door to a child’s creativity.

Let us try to imagine words having exactly the same purpose as building bricks. You have thousands of them and you can put them together in so many different ways to build either a simple collocation or a magnificent work like ‘Game of Thrones’. On the other hand, they can become absolutely meaningless and boring ‘on their own’. This is because words are originally meant as a tool with which you have to DO something or else they soon become objects of no interest and little value, because ‘on their own’ they make no sense to a child.

Looking at words from this perspective and putting them in a classroom environment, we can see many ways that practitioners could present them to children. Most often, especially with young learners, words are presented only as building bricks, which are looked at from different angles and need to be memorised.

In order to illustrate the point, I will use a concrete example. There is a coursebook that covers certain topics. The coursebook metaphorically presents a box in which some building bricks (words) are hidden. There is a limited number of bricks (words) for each topic, but there are no link bricks (ways, instructions) with which these bricks could be put together and built into a meaningful toy (sentence, collocation, phrase). On the other hand, the same box of bricks (the coursebook) has many descriptions (exercises) indicating what to do with single bricks (words), isolated from one another, looking at them from left and right, and occasionally from above (for example: “Colour or circle the picture that corresponds with the word ‘book’”; or “Connect the words to the correct illustration”; or, more challenging, “Group the words together by their colour”, etc.)

The exercises in these books have predetermined answers, and most often there is only one correct solution. Looking at those words time and time again presents very little challenge for the children, and can only hold their interest to the point of seeing whether the meaning of the word is understood. Then, according to most programmes, the children are done with these words and move on to a new set of words.

A far more sophisticated box of words can be offered through a story (picture books for young learners). Children are enthusiastic about this, because the box itself, metaphorically speaking, presents an object built of bricks. The words in the story are used in their meaningful purpose, they connect and ‘build’ the story together (what children see is a story, not the words themselves). What happens next? For children, most often a disappointing continuance of such a promising start: the demolishing of the story into individual words, which are observed from different angles through exercises like those described above.

The approach presented and described in the aforementioned article ‘Making Early Language Learning Effective’ shows how to use words meaningfully, how a sophisticated box of bricks (a story) can be demolished into a smaller set of bricks and then put together into new creations (games, doodles, etc.). This way, children are subconsciously exposed to set of bricks (words, collocations, chunks of words or phrases) and thus learn them in their own ‘natural environment’.

The challenge of how to teach children using words in sentences has occupied many teachers’ minds (and I believe researchers’ minds, too). I do not know if the approach presented above is THE ONE, but I can assure you that it works magnificently in practice.

Let us gradually demolish the castle (story), take away some useful bricks (words/chunks of words) and make a new building (sentence/text). It is important that the presented steps are introduced to the children in the listed order, because each step is the ‘foundation’ for the next one. It also has to be stressed out that before moving on to the next step, the children need to understand and comprehend what they are doing.

Employing activities with the Picture Dictionary and ‘doodling’ (Selič, M., 2014), the first step towards ‘real’ literacy and some ‘real grammar’, after the children have listened to a story, is encouraging children to put their CoolDoodles into ‘visualised sentences’ using the CoolTool cards (words).

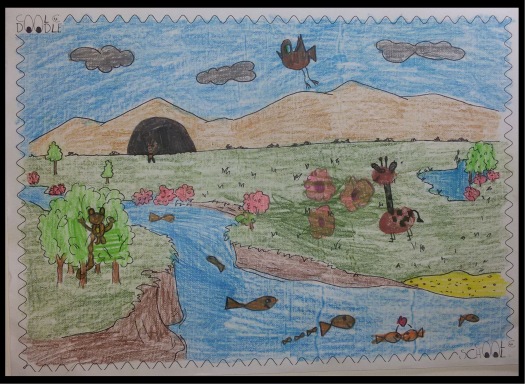

For better illustration, let us follow the steps towards visual reading through an example. The topic covered is ‘Wildlife’ and the story used to introduce the topic is ‘Roar’ by Margaret Mayo. After the storytelling and games that facilitate vocabulary learning (within the context), the children create their own individual doodles. The instructions are simple: draw/stick/fingerprint wild animals, place them in their environment and colour their habitat. There can be many animals of the same kind. Metaphorically speaking, the doodle is the ‘box of bricks’ and the ‘bricks’ are the pictures/illustrations/prints of animals and the features of the natural environment.

One of the finished doodles can be seen in Illustration 2. For oral practice, the children answer questions like ‘Where is the monkey?’ and each child finds their own monkey in their doodle. The children’s answers are short; for example, ‘on the tree’, ‘on the grass’, etc. Another question can be ‘What is on the tree?’, evoking answers such as ‘A green grasshopper’, ‘Two small monkeys’, etc. In other words, the ‘bricks’ (grass, on, the, river, by) are taken from the ‘box’ (the doodle) and used in smaller ‘construction sets’ (on the grass, in the river, etc.).

Illustration 2: The CoolDoodle ‘In the Wild’ (age 7)

I believe the relation between building bricks and words is now relatively clear. From now on, the text will only refer to words, but it is recommended that ‘for better visualisation’ the link between the two is constantly present in the reader’s mind.

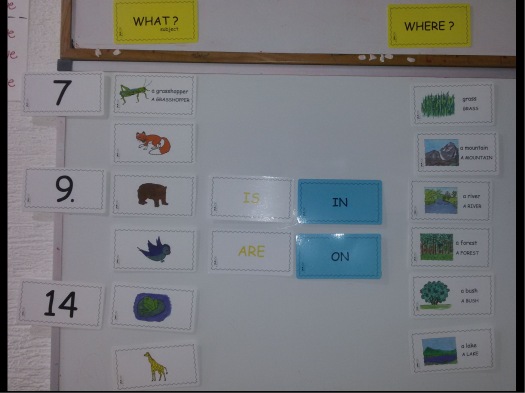

The same doodle is used a year later, with the same children (age 8), as a tool for the next exercise. The children place the CoolTool – Animal Cards under the question ‘WHAT?’ and the CoolTool – Nature Cards under the question ‘WHERE?’. In between the two columns, the verb ‘be’ and some prepositions are placed (see Illustration 3). Some animals have numbers in front of them indicating there are many of them.

The children read the sentences and create as many possibilities as they can. Every grammatically correct sentence is accepted as a correct sentence. Some of the sentences can be very creative, for example ‘Nine bears are in the river.’ (‘they were fishing’, was the child’s explanation.)

Unlike in workbooks, where there is usually only one correct answer (already predetermined, whereby children simply follow and do not discover), the exercise described above enables many correct answers, thus enhancing divergent thinking and nourishing children’s creativity. Additionally, children need to employ all of their (language) knowledge when turning pictures into words: transforming a singular noun into its plural form, using the correct form of the verb ‘be’, and selecting the appropriate preposition. The task can be both oral and written.

Illustration 3: Visual sentences.

Furthermore, the learnt vocabulary (animals and nature) is put into a context and is therefore meaningful for the child. Different types of CoolTool cards can provide different levels of the same exercise. The levels are used according to the aim and the level of the children’s knowledge.

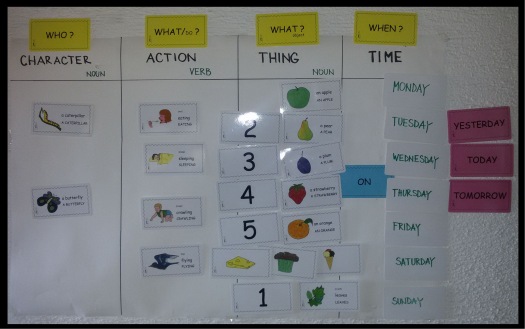

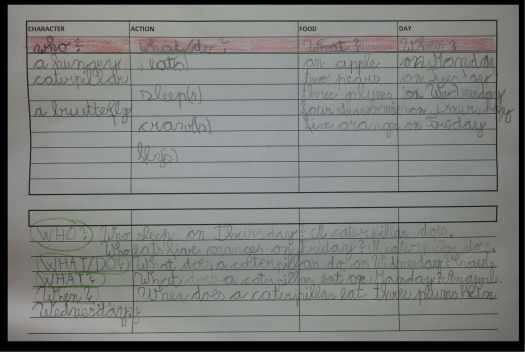

Balancing literacy and grammar, the CoolTool cards are used to visualise the summary of the story (see Illustration 4). In order for the children to become familiar with the time concept, it is recommended that stories are used in which the action is clearly spread over the period of one week, while at the same time using the days of the week to mark the repetition points of the action.

As the children read the sentences from the chart chronologically and from the children’s actual ‘time perspective’, they become aware of the time concept (for example, if the child reads the story on Tuesday, then Tuesday is the present, Monday is the past, and the days after Tuesday are the future). Furthermore, presenting question words in relation to their appropriate parts of speech, together with forming negative and interrogative sentences, is a good way to introduce auxiliary verbs within a context. Irrespective of the complexity of the grammar being introduced, all of its aspects are wrapped in a well-known context/topic/story and based on vocabulary that is taken from the story and thus known to the children. The children are again open to divergent thinking, as there are many correct answers/possibilities created by their imagination. Of course, all of this is gradually comprehended and learnt through different game-like and multisensory activities.

Illustration 4: Visual summary of ‘The Very Hungry Caterpillar’ by Eric Carle (age 9)

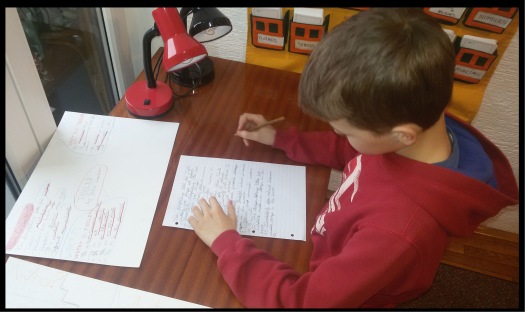

This sort of exercise is first performed orally, but also leads to its written equivalent. The children write a question, which is followed by the answer. Again, in order to put the visualised story (pictures) into sentences, the children need to employ all of their language knowledge, using the correct form of the verb, selecting the correct auxiliary verb, paying attention to the plural, etc. Illustration 5 shows the written equivalent of the visual summary.

At the age of nine, children who have been following the approach from the very beginning of their language learning (age 5) become relatively confident in speaking English. Conversation with them can be easily performed in English. In this way, the topic/story/plot, once having been comprehended with the exercises described above, serves as the basis for a follow-up Word Web activity through which more complex chunks of words can be put together.

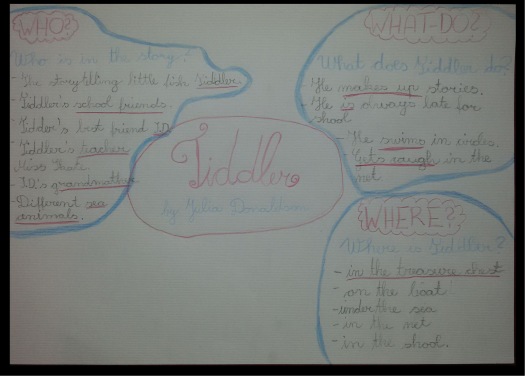

The story/plot is divided into three or four main parts according to the questions: WHO? (subject) – focusing on the characters in the story, WHAT-DO? (verb) – focusing on the action in the story, WHERE (nouns and prepositions) – focusing on places in the story, and WHAT? (noun) – focusing on things that appear in the story (see Illustration 6).

Illustration 5: Putting words into a visual summary.

Illustration 6: The Word Web ‘Tiddler’ based on the story by Julia Donaldson (age 9)

The children look for the answers in the picture book. Even though there is very little written text, the illustrations speak for themselves. Many answers are illustrated, and the Word Web simply puts words to them. Furthermore, the illustrations help the ‘bare words’ to obtain their descriptive adjectives. In the case of the ‘Tiddler’ picture book, for example, the question ‘WHO is in the story?’ could be met by the ‘bare’ answer ‘Tiddler’. But who is Tiddler? To the children, this seem obvious because they know the story. However, when it is pointed out that not everybody has read the book and that the answer should therefore be more descriptive for those who do not know the story, new answers suddenly arise: ‘a fish Tiddler’, ‘a small fish Tiddler’, ‘a storytelling fish Tiddler’, etc.

As can be seen in Illustration 6, the answers are put together in a way that easily provides support for forming more complex sentences. The children first read them, ask questions, contradict them, etc., and then later put them into different combinations. Even though a lot of short answers are already provided, the wide range of possible combinations enables the children to use their creativity. At the end, every child can write their own version of the text, mixing sentences together to follow their own imagination, while at the same time practising writing, spelling, grammar, etc. (see Illustration 7)

Illustration 7: Sentences created from the Word Web (age 9/10)

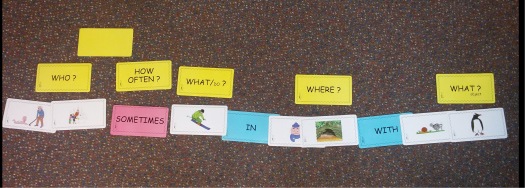

This rather challenging exercise provides the basis for some real visual grammar practice and can cover all of the tenses known to the children. The CoolTool cards cover 700 of the most frequently used words as well as additional ‘grammar cards’ that cover auxiliary verbs, prepositions, question words, personal and possessive pronouns and time adverbs. For the purpose of the exercise, the cards are divided into groups, each of which contains words that can form a sentence when combined.

The child places the cards one after another in the correct order to form a sentence. The task is to find as many sentence combinations as possible, and to put them in the affirmative, interrogative or negative form. In order to find the sentences, the children simply change the positions of the cards or use the correct auxiliary verb according to the tense (see Illustration 8). With this task, we again enhance the children’s creativity, divergent thinking and imagination, while at the same time employing all of their language knowledge. Once the sentence is assembled correctly, the children can copy it in order to practise writing.

Illustration 8: Sentence making (age 9/10)

Illustration 9: Sentence making (age 9/10)

‘My old grandfather sometimes skis in the cold cave with the slow penguin.’

The ‘traditional’ and ‘established’ approach to language learning through text/work/exercise books encourages convergent thinking, kills children’s creativity, does not allow sufficient time for playing games and often results in bored children and frustrated teachers. The method described above offers an alternative: a context-based, holistic, multisensory, ‘gamified’, creative, flexible, challenging, child-centred and motivating approach. Furthermore, one set of teaching tools can be used with all children from the age 5 to 10/11.

Carle, E. (1969). The Very Hungry Caterpillar. London: Puffin Books.

Donaldson, J. (2007). Tiddler, The Storytelling Fish. London: Alison Green Books.

Kyung Hee Kim. (2011). The Creativity Crisis: The Decrease in Creative Thinking Scores on the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking. Creativity Research Journal, 23:4, 285-295

Marjanovič Umek, L. (2004). Razvojna psihologija. Ljubljana: Filozofska Fakulteta.

Mayo, M (2006). Roar! Sydney: Orchard Books.

Selič, M. (2014). Making Early Language Learning Effective. HLT magazine.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Kindergarten Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|