Identifying and Addressing the Relevant Factors Which Impede ELICOS Student Progress

Rosemarie Paspaliaris, Australia

Rosemarie Paspaliaris is a Senior Language Educator at RMIT English Worldwide in Melbourne, Australia. She holds a Bachelor of Arts (Monash University), Diploma of Education (Monash University) and a Post Graduate Bachelor in Educational Studies (TESOL) from the University of Melbourne. Her research interests include developing methods for ‘unlocking’ student language learning potential, enhancing learner autonomy and identifying students at risk of failure.

E-mail: rosemarie.paspaliaris@rmit.edu.au

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Students ‘at risk of failing’

Student identity

Primary research in the classroom

Methodology

Students in the study

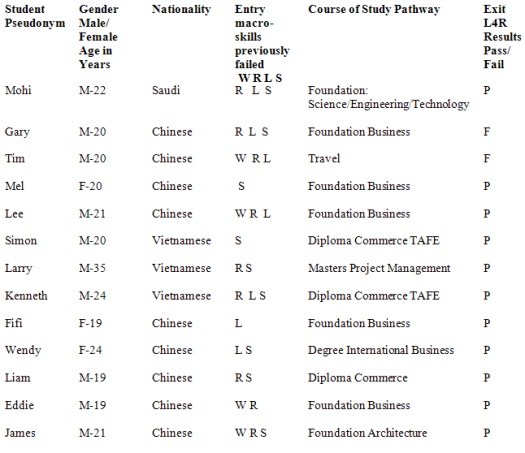

Student details table

Transitioning to new study environment

Discussion of main findings

Results

Student factors hindering progress: Gary, Tim, Mohi and Simon

Student attendance and exam performance

Discussion: Addressing the main factors hindering progress

Practical considerations

Conclusions

References

Teachers and teaching institutions face many challenges when grappling with students who enter a cycle of failing. In this case-study, 13 Intermediate Repeater students (L4R Class) were investigated with the view of identifying and addressing the underlying factors and associated elements which impeded their language learning development. The factors most commonly found were absenteeism, disengagement, anxiety and feelings of vulnerability. A new approach, using observational analysis in recording the profiles of student progress by documenting new language learning progress and addressing the impeding factors which affected students’ learning. This work was part of the continual teaching methodology development for ‘at risk’ students. The potential use and development of personality traits as a tool in the early detections of ‘at risk’ students was also briefly explored. The impeding factors were addressed by counselling, close monitoring, encouragement and addressing their accountability for their actions. This new approach had a success rate of 85%.

The growing importance of English as a global language has been a strong impetus for many international students to pursue studying abroad in order to gain competence in English and an overseas qualification at RMIT English Worldwide (REW). REW has many new markets and ongoing research programs which feed into the continual development and upgrading of teaching methodology, (particularly for students at risk of failing), with the view of maintaining a competitive edge within the education sector.

As an impetus for unlocking learning potential, a certain element of risk needs to occur. Risk as defined by Wilson (2012) is ‘not an inherent quality of individual students, as in the term at-risk student’, ‘risk is a function of the interaction between a student and their university’. The external factors that can affect student language learning are not always easy to identify and the impact can have a detrimental effect on students’ language learning.

Some of the external factors that have been identified include level of prior knowledge, study expectations, social connectedness, cultural variations in styles of thinking and their sense of identity. Lizzio (2006) shows that student level of engagement can be predictors for academic success and retention rates, and refers to the 5 senses of student success based on sense of capability, purpose, resourcefulness and connection with the ‘identity of the student’ at the heart of this.

Thanassoulas (2002) points out that educators need to be aware that language teaching needs to take into account a variety of factors that are likely to promote or even mitigate against success’. He states that ‘language is part of one’s identity and is used to convey this identity to others’. However, the challenge teachers face is how to ‘draw out’ the students’ expression of identity, particularly in repeater students, so that they can have their own self actualisations within the classroom realised, given, that their experience of failure has already exposed feelings of vulnerability. Some students could be feeling stressed in adapting to a new environment and the classroom learning situation which demands cultural variant in styles of thinking.

In order to investigate ways of maximising opportunities for success, a classroom based case-study of 13 Intermediate Level repeater students (L4R Class) was conducted through primary research with teacher as observer and participant. The students were investigated with the view of identifying and addressing the underlying factors and associated elements which impeded their language learning development over a 5 week intensive ELICOS program at RMIT English Worldwide (REW).

The L4R cohort displayed factors which hindered students’ progress, which were identified through first hand observational analysis and monitoring student progress. I had the privilege of collecting ‘evidential’ data of behaviour and recording this in my reflective journal. Having had a close trustworthy rapport between the students meant that through my familiarity with them there was a measure of confidence with the ongoing discourse, which was central to my research. I recorded highlights and important breakthroughs, which may relate to addressing some of the factors which impeded students’ development as well as particular details, which I gleaned from their student files in student services. These changes were also taken into account in determining a student’s learning developmental plan, which could help support diagnostic analysis and implementation methods .The ongoing consultative process with other teachers on the course program were also considered, so I could best provide pastoral care when needed.

This class consisted of 13 Intermediate Level Repeater students, which included 10 males and 3 females. The ages ranged from 18 years until 28 years old, the nationalities of the group were predominantly 9 Chinese, 3 Vietnamese, and 1 Saudi student. There were 10 males and only 3 females. The students’ prior end of course results show the number and type of macro skills they had passed or failed. It was important to reflect on the past exam performance in relation to their future study pathways.

Many students who choose to study in Australia have been successful students in their home countries; however, certain problems emerge when living in a different linguistic and socio cultural environment. This could result in failure to effectively manage new ways of thinking, learning and surviving in their daily living which may lead to being unsuccessful in passing their exams .It was noted that in the first week in the L4R class, the road to “accepting having failed” was an arduous task for some and a major hurdle, shock, source of apathy and bewilderment for others, which meant encouragement, fostering a positive mind set by consulting with each individual and collaboratively devising a study plan and working out strategies for the class collectively to reach assessment goals.

The L4R repeater students displayed a range of emotional, behavioural and language learning issues which affected language learning development. The factors which impacted on their learning progress included lateness, poor attendance ,loss of confidence, emotional issues, over-tiredness, compulsiveness, disengagement, failing assessments and lack of social connectedness with each other. This was compounded with their poor study skills and lack of motivation.

These results of main findings highlighted many factors which were continuously addressed through my first hand encounters in the socio cultural microcosm of the learning classroom. The most pertinent hindering elements identified from the individuals have been characterised below, which may appear overly negative. However, I have just extrapolated these hindering elements for the purpose of the study through brief descriptive entries from my note-book, which included directly observable evidential comments. The personality issues highlighted may indicate that some form of personality testing would be useful to distinguish learning styles and serve as a guide to the classroom teacher.

The 13 students displayed a collective array of hindering elements that impacted on their progress; four students have been selected as demonstrating particularly discernible diagnostic factors which impacted on their learning.

1. Gary - Chinese

When he started the course, his attempts at tasks in class and behaviour showed the Chinese cultural fear of “losing face” as he displayed anxiety when he needed to participate and minimally applied risk-taking strategies. He often got embarrassed easily, worked alone and withdrew from working with others. He often avoided working with others and left the room when asked to work with others. He often lacked energy and was often extremely over-tired. He lived in university lodge accommodation and mentioned he often was engaged in many hours of computer gaming with his friends, staying up and playing for many hours and said he didn’t want to come and study in Australia. He was often referred to Student Services for support.

2. Tim - Chinese

Tim lacked focus on tasks and often didn’t keep up with the pace of class, and most tasks were not completed. He was friendly with others and often distracted others from learning by talking about things related to his computer gaming. He appeared dreamy, unresponsive and preoccupied. He was not on a study pathway. It was his parents’ decision for him to be in Australia as they wanted to open up a business here. He stated that he would probably work in his parents’ business when they arrive in Melbourne in a few months. He rarely focussed on learning tasks and often spent quite some time with his head down on the table. He said he lived alone and would sleep in class and asked students sometimes because of his excessive sleepiness to walk home with him as he lived close by. He was often referred to Student Services for support.

3. Mohi - Saudi

Mohi took risks when challenged, asked questions to the teacher and sought support when necessary .He worked well with others, wanted to improve and completed class tasks. He told me he had some health issues and needed hospital visits to monitor his health which was supported with medical certificates. He was well adjusted to independent living alone as he said his accommodation was comfortable.

4. Simon – Vietnamese

Simon took many risks in learning. It was interesting to note that he worked well with others especially Vietnamese classmates. He did not accept he had failed for one week. After coming to his own self-realisation through one on one pastoral care, and getting him to plan his goals and gain a realistic idea about his skill level, he gained his confidence. He decided to assess his skill level in terms of IELTS proficiency, so mid -course he enrolled in an IELTS test before the final exams.

It is quite well known that there is a strong relationship between student attendance and exam performance, showing that missing classes does significantly affect exam performance as well as mastery of the target language and course content (Fay, 2013). For ELICOS students on an Australian study visa, compliance stipulates minimum class attendance of 80%.

Case study students Gary and Tim did not pass the L4R course, had just barely satisfied the minimum attendance rate ,whereas the other 11 students’ rate of attendance varied from 90 to 95% showing that greater attendance can contribute to better chances for success.

The following main areas that were addressed are as follows:

Building rapport with teacher.

A safe environment needs to be fostered for the students so that the culturally ingrained factors which inhibit this safe environment can be addressed. The modelling of ‘intellectual risk-taking’ used in this study by teachers helped students ‘learn how to learn’ as described by Siering (2012).This process is applied by small incremental stages of learning whereby students can accomplish tasks and feel proud of their achievements and be guided to further progress. Some of the L4R students have shown cultural influences in their ability to relate informally through the student-teacher relationships by avoidance strategies such as not making eye contact, leaving early without informing the teacher and not conforming to protocols of the classroom. The addressing of these culturally ingrained factors is similar to that described by Thanassoulas (2002).

Facilitating interaction which addresses a supportive classroom atmosphere.

Learning styles and students commitment to learn, classroom communication, and group dynamics were addressed as illustrated by Wilson (2012) and Siering (2004). Wilson stresses the importance of student social engagement in learning. The students needed to learn from one another via the exchange of ideas, learning styles and ways of communicating. Initially, group dynamics among the L4R class students was fragmented and characterised by lack of co-operation which impacted on the students’ commitment to learn. By use of topics related to their collective interest, improved cohesiveness was promoted, as evidenced in the students’ interaction with each other, and this led to a group history being developed. Through this safe place to take risks, the pain of possible anxiety of making mistakes for vulnerable students was lessened.

Creating realistic learner beliefs and goal orientation.

Expected rate of progress, realistic expectations, motivation, homework completion, writing and expression skills, accountability and attendance issues were managed in a similar way to that described by Thanassoulas (2002). Thanassoulas points out the importance that students discover for themselves the optimal methods and techniques for learning that they realise that learning is a continuum and they need to maintain their motivational direction. With this L4R class, there were lapses of student motivation by some students. In one instance, during week 3, Eddie did not attend often and was overtired when he did. Previously, he was a conscientious and highly motivated student. One to one counselling with him identified that he was over committed to his outside endeavours, playing basketball and over socialising. After a few one to one counselling sessions, he fully realised and accepted that his studies were being neglected and he might fail. The positive outcome was that he changed his behaviour, which resulted in a marked improvement to his attendance, motivation and assessments. Hadfield and Dorneyei (2013) believe that it is important to engage students through positive desirable visions of themselves, making them as realistic and multisensory as possible. In the L4R class, a successful series of activities that was incorporated into the course was when the students downloaded an online application, "Create your own character" on their phones. They used this to create a visual representation of their future successful selves; through these personas they expressed themselves in group discussion with their peers. Through teacher facilitation when creating their pictures, they described their avatars through paragraph writing and giving an oral presentation to the class, and their visions were drawn out by answering questions from their peers. This activity stimulated growth and helped contribute to the maintenance of the motivation of the class group.

Increasing learner satisfaction.

Some repeater students didn’t submit their writing homework tasks or complete class tasks ‘because they had passed essay writing last course’. When having discussions with students, Lee, Eddie and James, I helped them realise that by further developing their writing skills, through scaffolding tasks and using checklists for individual self-assessments, peer check and teacher feedback it would benefit them in other areas such as grammar, vocabulary and expression etc. It was the process of learning, scaffolding writing tasks that was crucial to their development. Consequently, they made significant changes in their perspectives and improvements in their grammar in writing tasks as they developed autonomy in their writing and completed several extra tasks outside of class.

Building confidence.

Thanassoulas (2002) believes that it is important to increase learner success by displaying work, encouraging them to be proud of themselves and celebrate success as well as using rewards. However, many students were grade driven and focus on performance outcomes rather than the process of learning itself as this is culturally ingrained. Feedback through peer and teacher and celebrating their achievements were pivotal in their progress.

Raising health awareness.

The lifestyle habits of two students had a negative impact on their progress. There were diet-related allergic reactions as evidenced in red rashes on Eddie’s and Liam’s faces. This further led them to lose confidence and become isolated. So pronounced was Eddie’s self-consciousness on the matter of his red rashes, it necessitated him to wear a mask, which meant that this barrier made it quite difficult for him to feel comfortable participating as part of the group. When the allergy had subsided, as part of the collective addressing of factors, the importance of healthy diet was incorporated into some of the lessons.

Creating learner autonomy.

The students in L4R showed underdeveloped study habits such as poor note-taking, poor attendance, ability to stay focussed and were easily distracted. Lessons were given on the importance of taking notes, how to abbreviate, concentrate on key aspects of classroom approaches to learning and by using notes of grammar points and tips for assessment for referral for revision. Furthermore I reiterated the importance of and contributed to helping students extend and build social connectedness by assigning small projects in ILC for group preparation and oral presentations to develop autonomy and forge links through study buddies. I also developed student time management skills by spending time in class on calendar updates on phones, explaining the importance of adhering to deadlines and regular attendance. Moreover, I referred students to special workshops and conversational classes to address phonological problems in speaking for better communication in preparation for assessment. This was reinforced through continual practice and feedback of participation in mini tutorials which were a regular and integral aspect of the lessons and were used as a lead into or follow up of class activities. Some study issues were addressed by offering support and assistance through guidance, recommending materials and if need be referral to the Independent Learning Centre teachers.

It is worthy to note that by addressing the factors, the interplay of these factors were not always known, but what was discernible was that after the first two weeks of the course the class’s progress was gathering momentum and that by week 3 there was a collective ‘phase shift’ as students forged bonds, were working to reach their goals and were beginning to overcome their hurdles or obstacles.

The implications from the result of this study can be offered as suggested strategies for teachers to better effectively manage the ‘risk of failing’ repeater students:

Classroom atmosphere

Establish a classroom culture whereby students establish ‘bonds’ with each other through mutual support in tasks by ‘strategising’ the student working parties and groups. These ‘bonds’ can develop into working and mentoring relationships. Teachers can encourage stronger skill level students with weaker ones, polar opposite personalities, confident with less confident students in order for students to learn flexibility in learning with and from different characters and different learning styles.

Classroom environment

Devise activities which allow for greater learner engagement through designing tasks around spatial awareness and flexible seating arrangements. The tasks could be centred around stations or posts whereby students move freely through open spaces sequentially, or randomly, through live debates, timed/untimed, with various types of music which encourages flexibility and ease of movement, activates the brain, stimulates responsiveness; poster wall debates, standing debates, line conversations and circular musical chair activities.

Behaviour modification

Train students to develop an understanding of the consequences of negative behaviour which can have a detrimental effect on their learning and reinforcing through reward and genuine praise by reinforcing classroom rules which were class negotiated. Allow students opportunities for development of mutual respect and greater accountability for understanding that higher rate of attendance has a greater determining factor for success.

Critical thinking and logical reasoning

Incorporate tasks which require inquiry and critical evaluation in logical puzzles, activities, reading exercises and reading different genre types including graded readers. Activate students’ thinking skills by encouraging thinking from different perspectives, e.g. in short clear thinking exercise, getting them to use the process of deductive and inductive reasoning. Reading short chapters of a graded reader on a daily basis can stimulate further reading of novels and other types of reading. It can stimulate the need for seeking out more challenging mental stimuli in reading a variety of reading materials for independent learning.

Tech-savvy creative learning and tactile artistic opportunities

Capitalise on the incorporation of creative apps as a stimulus of creative fun learner engagement, which is a stepping stone for creating drawings of characters, writing and oral presentations. This can be further incorporated into an artistic medium through coloured pen drawings further enhancing learner preferences through visual, auditory and kinaesthetic ways of learning. By evaluating student ‘performance’ in these tasks, this can lead to teachers’ greater awareness and understanding of learners’ optimum ways of engagement and enhance learner potential as students are on a “roll” which can gain momentum in learner motivation and lead to establishing the building blocks of success.

The observational analysis, identification and addressing of impeding factors and intervention strategies used in this study of 13 L4 repeater students had a success rate of 85%. A small phase shift was first observed (week 2) within the student group with regards to them responding positively and starting to better manage the factors which were impeding their development. This positive change continued and built momentum with the majority of students in weeks 3 and 4.

The factors that affect students are intrinsically linked to their personalities. The relationship between personality, the disposition factors (part of personality) which can affect a student’s ability to learn have been widely researched by Dorneyei (2005) and Verhoeven and Vermeer (2002).

Although further work is required, the implications of this study could involve personality testing of students. This has not been commonly used as a tool in managing a student’s development to date and may prove very useful in the identification of students’ likelihood of failing, given, that personality and behaviour are intrinsically linked. Furthermore, personality testing is widely utilised in many other industries such as finance and human resources.

Dorneyei, Z. (2005) The Psychology of the Language Learner: Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers London.

Fay, R.E. (2013) “Absenteeism and Language Learning: does Missing Class Matter?” Journal of Language, Teaching and Research, Vol 4, No 6, 1184-1190.

Hadfield, J., & Dornyei, Z.(2013), Motivating Learning. Harlow:Longman.

Lizzio, A. (2006), “Designing an Orientation and Transition Strategy for Commencing Students”, Griffith University: First Year Experience Project. Retrieved from http//:www.griffith.edu.au

Siering, G. (2012), “Why risk and failure are important in learning”, CITL Indiana University, Bloomington. Retrieved from http://www.citl.indiana.edu

Thanassoulas, D. (2002), “Motivation and Motivating in the Foreign Language Classroom” The Internet TESL Journal, VII, (11)

Verhoeven, H. and Vermeer, A. (2002),”Communicative Competence and Personality Dimensions”, Applied Psycholinguistics, 23, 361-374

Wilson, K. (2012) Engaging commencing students who are at risk of academic failure: Frameworks and Strategies. FYHE Conference June 2012. Retrieved from http://www.griffith.edu.au

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English Language Improvement for Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English Language Improvement for Adults course at Pilgrims website.

|