Editorial

The article will be part of a book soon to be published by Wei-Wei Shen.

Exploring L2 Learners’ Cultural Awareness: Explaining Chinese (L1) Cultural Keywords in English

Wei-Wei Shen, Taiwan

Dr. Wei-Wei Shen is an assistant professor of Feng Chia University in Taiwan. She received her M.A. in Applied Linguistics at Essex University (UK), and her Ph.D. in Applied Linguistics & TESOL at the University of Leicester (UK). Her research interests include vocabulary teaching and learning, cultural keywords, and academic writing. E-mail: wwshen@fcu.edu.tw

Menu

Introduction

Chinese core values and keywords in Confucianism

The selection of the six Confucian keywords

Materials and methods

Results and discussions

Conclusion

References

Appendix

Explaining one’s own culture through one’s first language (L1) may be challenging because explanations would be complex or incomplete. Furthermore, it may be difficult to introduce L1 culture through a second language (L2) when there are no immediate translations between two languages (e.g. Wierzbicka, 1991, 1997). Wierzbicka (2001, p. 7) clearly indicates that “most words in any one language are language-specific and do not have semantic equivalents in other languages”. However, despite the difficulty in translating cultural keywords (see next section for further information), culture is a basic but important element of the modern language pedagogy (e.g. Byram & Esarte-Sarries, 1991; Hall, 2002; Hinkel, 1999; Willems, 1996). Harklau (1999), for example, has indicated that language students in America are frequently assigned writing topics such as talking about their home cultures, or comparing L1 with L2 cultures. Thus, if L1 culture is a learner’s roots of identity (e.g. Hall, 2002), then L2 learners have to know how to describe L1 cultural concepts in an L2.

However, Taiwanese learners of English can get much input of English (L2) cultures but not Chinese (L1) cultures from the modern course books designed by international publishers. For example, a leading English language teaching publisher, Longman, has published materials suitable for teaching of English cultures with the keyword like “Britain”, “USA” in the book title. Therefore, when English language teachers in Taiwanese universities tend to use these ready-made materials from international publishers, it seems likely that few learning opportunities in this educational context are offered for learners to interpret their own cultural concepts through English. The aim of the present study is then to explore what Taiwanese university students’ cultural awareness may be like if they need to choose English words or phrases to explain a set of Chinese cultural concepts.

The six keywords (or concepts) in the present study include ren (‘humanity’ as a typical English definition found in the dictionary), li (‘propriety’), xiao (‘filial piety’), de (‘virtue’), he (‘harmony’), and junzi (‘gentleman’). These words represent the core values of Confucianism (or Neo-Confucianism), that is, Confucius’ and his followers’ teachings on ethics, morality, relationships, rituals, which have influenced Chinese people for over two and a half millennia (e.g. Berthrong & Berthrong, 2000). The first five of them have English abstract nouns as one of the typical English equivalents found in various publications. But the last one is a noun referring to a person with the essence of the goodness consisted in the first five words. So these six Confucian keywords are put together as a small set in this study.

The following first introduces the importance and the criteria of selecting these six Chinese cultural keywords. Then it reports on a study used to explore whether Taiwanese university students of English (i.e. the subjects drawn from one of the Confucian regions, Taiwan) agree with the pre-selected definitions and translations.

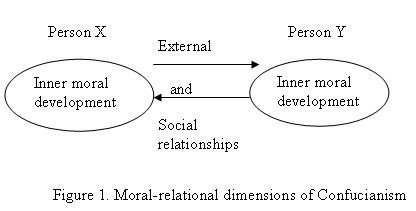

Confucianism has been under heated discussions and published in languages other than Chinese in the world (Berthrong & Berthrong, 2000; Yao, 2000). Its core value is to be ‘humane’, i.e. to pursuit ‘humanism’. Therefore, its ultimate intention, on the one hand, is to cultivate a great man to have all virtues (i.e. the internal moral development or self-cultivation of the individual person), and on the other hand, to have relations with others (i.e. the external social and moral development of relations between people or between the individual person and society). Thus, Confucianism includes moral and relational dimensions as shown in Figure 1 (Shen, 2001).

When many Chinese people refer to important concepts of their cultural heritage, they mention the ones in Confucianism. For example, the study of Shen (2001) showed that when Taiwanese university students were asked to provide the keywords that represent the Chinese culture, they quickly mentioned the concept of xiao. This keyword is obviously the crucial value of “Confucianism in particular and Chinese culture in general” as Berthrong & Berthrong (2000, p. 57) proclaimed. Although this does not mean that Confucianism is considered as the only cultural heritage of the Chinese, Berthrong & Berthrong (ibid.) mentioned that studying Confucianism is the key to the understanding of Chinese culture.

There is a consensus that every language consists of unique cultural keywords which reflect the core values of the culture (Chappell, 1994; Goddard, 1997, 1998, 1999; Goddard & Wierzbicka, 1994, 1997; Myers, 1996a, 1996b; Wierzbicka, 1985, 1991, 1992a, 1992b, 1996, 1997). In one of her research, Wierzbicka (1991) studied six Japanese keywords which have been recognized to have important features of Japanese cultures but they are hard to be explained through English equivalents. Thus there must be Chinese keywords which can reflect the cultural value system as Figure 1 depicts, but they may be hard to be translated in English.

Apart from the set of six cultural keywords included in this present study–ren, li, xiao, de, he, and junzi (see above and Appendix A for their common English equivalents), there are other keywords that may be regarded as core values including yi (‘righteousness’), zhi (‘wisdom’), xin ( ‘faithfulness). Within this conceptual dimension, many of these essential and core virtues in Confucianism have been well explained or discussed (e.g. Berthrong & Berthrong, 2000; De Mente, 1996; Gao & Ting-Toomey, 1998; Hall & Ames, 1987; Hsu, 1971; Huang, 1997; Smith 1983).

However, the studies of Cortazzi & Shen (2001) and Shen (2001, 2007) only focused on the first six cultural keywords as a set because these words were noticed to be frequently discussed by different scholars and clearly regarded as the core of Chinese cultural words. For example, Hall & Ames (1987), in their highly regarded study of Confucian philosophy, comment at length on ren, li, de, he, junzi, and briefly on xiao. Five words out of the six, ren, li, xiao, de and he, were collected as current Chinese cultural words in De Mente (1996). Ren, li, xiao, de, and junzi are explained as key terms for understanding The Analects of Confucius in a preface to the translation by Huang (1997). Moreover, these six words are also found in classic Chinese primers like San Zi Jin ( ‘The Three Character Classic’) and Qian Zi Wen ( ‘The Thousand Character Classic’) published in various places, including Mainland China, Taiwan and Singapore (Giles, 1984; Li, 1997; Shi, 1987; Xu, 1990; Xu, 1994). These primers have been popularly used as supplementary materials for pre-school literacy learning and moral education. Thus these keywords not only represent the core cultural values of Confucian heritage culture but are also basic Chinese words for literacy learning.

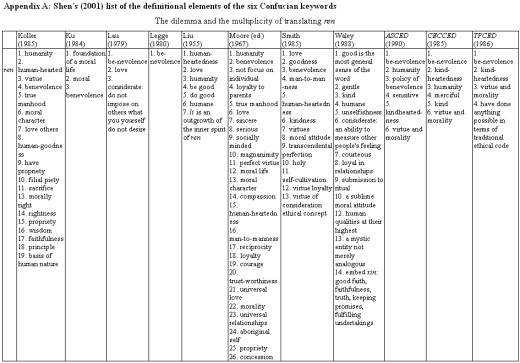

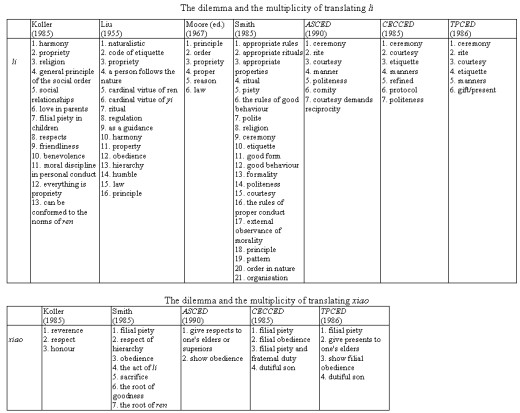

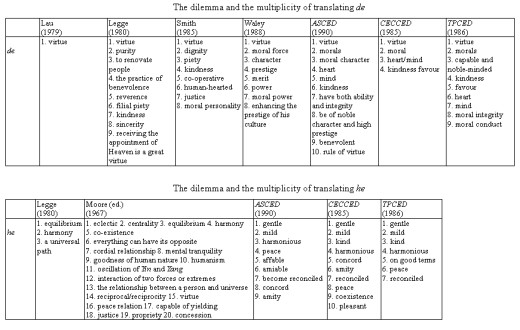

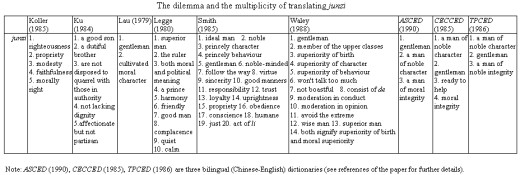

However basic or frequent these six words are, it is difficult and complex to find the equivalent concepts in English (Cortazzi & Shen, 2001; Shen, 2001, 2007), because Chinese and English represent two different cultural and philosophical orientations. In addition, the studies of identified that. In fact, the English translations used by different scholars for these words have shown a wide range of separate terms (Appendix A). For example, Lau (1979) used ‘virtue’ as a main definitional element for de, but Legge (1980) came up with several terms for the same Chinese keyword, such as ‘virtue’, ‘purity’, ‘the practice of benevolence’.

Most importantly, it was noticed by Cortazzi & Shen (2001) and Shen (2001, 2007) that one single English definition has often failed to explain or to distinguish the meanings of the six Chinese keywords. In other words, the same English terms are used as part of the translations for different keywords. For example, ren is ‘kindness’ and so is de. In fact, Shen (2001) has modeled the overlapping concepts of the six words including ‘humanity’, ‘kind’, ‘virtue’, ‘morality’ and ‘gentleman’.

Overall, as there is the complexity and the overlap of explaining these common Chinese keywords in English noticed by the former relevant studies, these words serve as good examples to explore further regarding how Taiwanese learners of English may select the English (L2) terms to explain the six Chinese (L1) keywords. Furthermore, investigating cultural keywords is worthwhile because vocabulary is noticed to be one obvious element to explore one’s awareness of the semantic differences between two different languages (Hatch & Brown, 1995; Saeed, 2003; Wierzbicka, 1997).

The researcher attempted to establish several criteria for developing the elements of defining each of the keywords in this exploratory study. In order to form a questionnaire, the current research referred to Shen’s (2001) list of the translations and definitions of the same six Chinese cultural keywords, i.e. ren, li, xiao, de, he, junzi. This list shown in Appendix A includes translations and definitions picked up from various publications (Koller, 1985; Ku, 1984; Lau, 1979; Legge, 1980; Liu, 1955; Moore, 1967; Smith, 1985; Waley, 1988), and different dictionaries (ASCED, 1990; CECCED, 1986; TPCED, 1985).

However, the current study did not include every single element found in Shen’s (2001) list to avoid forming an exhausted length of the questionnaire. Instead, the current study selected some elements frequently seen in the list because they were found to appear more than once. As indicated before, different scholars or lexicographers have used the same terms to explain the same cultural keyword. Moreover, if the overlapping and similar English translations were found in different cultural keywords, they were also included. For example, although ‘a good son’ for the keyword junzi was only used by Ku (1984), ‘a good son’ may be a common element to explain another keyword xiao. In fact, two dictionaries TPCED (1985) and CECCED (1986) included ‘dutiful son’ as one of the definitions. Thus, this particular item was still included in the keyword junzi due to the overlapping concept. Similarly, Smith (1985) mentioned junzi may include a sense of ‘obedience’ which may not be seen as a common definition of this particular keyword in Appendix A, but such an element was also noticed to be included in the keyword xiao according to three dictionaries ASCED (1990), TPCED (1985) and CECCED (1986), so this particular definitional element ‘obedience’ was kept for the two cultural keywords - xiao and junzi. It is important to note that these existing translations and definitions, termed as definitional elements in Shen’s study (2001), were found to be used in various contexts. Thus all the elements may not have the same word classes or part of speech due to the contextual effect.

After making a decision of selecting the definitional elements for each keyword based on the above criteria, the researcher then formed a checklist with a five-point Likert scale – from the left-hand side (strong disagreement) to the right (strong agreement). Respondents were required to show how much they would agree with each element used to explain each target keyword. If the respondents were not sure (or did not know) that any particular English element can be used to explain any keyword, they were allowed to mark on the columns towards the “disagreement” side of line. On the contrary, the subjects may pick up the option towards the “agreement” side of line if they were certain of the item. This system was intended to make obvious contrast between the “negative” and “positive” side of the response when the subjects reflected their knowledge. Thus when the response of the particular questionnaire item turns to be on the side of the agreement, the English element was accepted or recognized as a part to explain the meaning of the Chinese keyword. Although it might raise a question regarding what subjects’ “disagreement” on the particular item really meant due to the two possibilities as mentioned, using a questionnaire with closed questions allows the researcher to quickly explore participants’ vocabulary knowledge in terms of breadth (Read, 1997, 2000), i.e. which definitional elements with the limited range may be agreed or disagreed by the selected subjects in the current study.

The questionnaire was given to 80 English-majors studying in a private university in the central Taiwan area. The researcher conducted and collected questionnaires in various courses - Interpretation, Translation, Semantics, Writing, Practice of English Language Teaching and Learning, and Theories of English Language Teaching and Learning. These subjects answered each questionnaire item themselves without looking up the dictionaries in class. They had to decide whether they agreed or disagreed on each item which might be used as one of the Chinese keywords’ definitions based on their own present knowledge. As they did not have to write down their names on the questionnaire, they would not feel embarrassed to admit they were not sure what something might mean in English.

Ideally perhaps obtaining qualitative data from interviews might reveal more of findings, but the present study did not employ this research method because of two reasons. First, subjects, if not all, may not be able to provide definitions of the keywords actively, spontaneously, and productively in the interview (Shen, 2001). Another important reason is that the researcher of the current study did not find it feasible to ask voluntary or enough participants to get involved in this study. Thus a feasible solution was to ask students to take about 30 minutes in class to complete the questionnaire only. Conducting interviews in class surely was more time-consuming and would hinder the normal class schedule. Therefore, in order to save time and make this survey possible, the researcher judged that the questionnaire investigation having pre-selected translations and definitions in print may serve the purpose of triggering participants’ word knowledge and supplying their responses in a short time and with the minimum of fuss.

As indicated earlier, the selected definitional elements (see the full list in the following tables) were all found to be used for explaining a set of the six target words, so presumably the subjects were supposed to agree that all of the elements can be part of definitions. But the question that may be interesting to find out is “what would be the elements strongly agreed/disagreed by the majority of the selected subjects?”. In order to answer the research question at the exploratory stage, responses were quantitatively analyzed by means of descriptive statistics with the help of SPSS. The coding system used to analyze the data was from 1-5 representing the least agreeable to the most agreeable term. Therefore, the result obtained from this study was interpreted in a way that if the mean score of the questionnaire item is over 3, then the higher the mean score is, the more the respondents agree that the one is used for interpreting a Confucian keyword. Nevertheless, any questionnaire item with the mean score below 3 was considered as a translation less agreeable or recognizable.

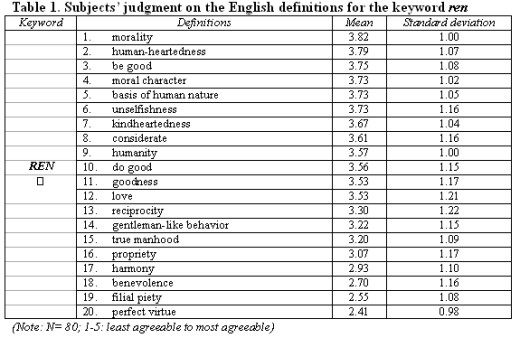

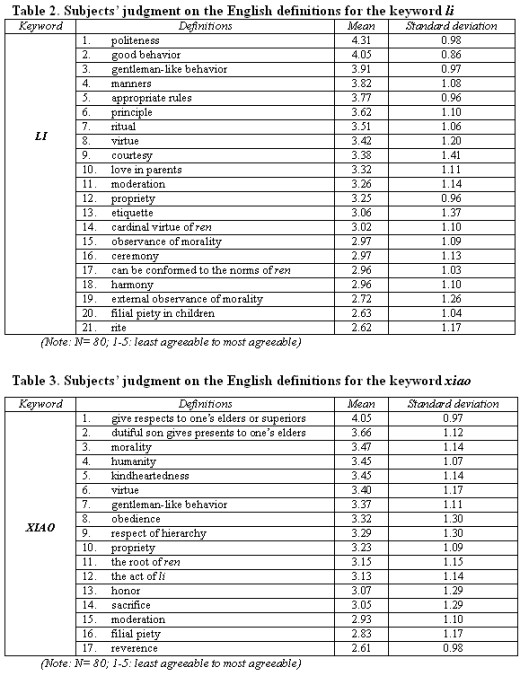

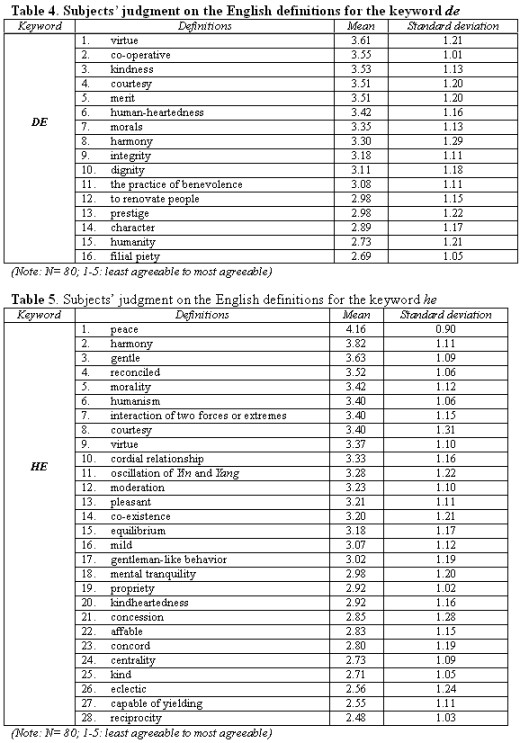

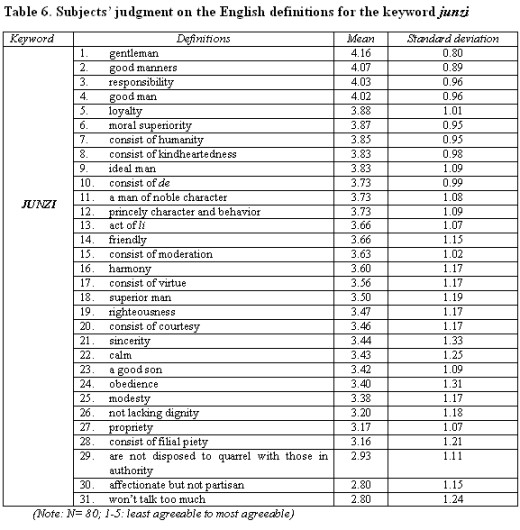

The following six tables display the ranking of the subjects’ responses to the definitional elements of each word according to the degree of their agreement. The overall results show that Taiwanese learners of English at the university level sampled in this research agreed with many definitional elements of each keyword (with mean scores above 3 out of the five scales, i.e. the “agreement” side of line). Table 1 has 16 items out of the overall 20 options, Table 2 has 14 items out of 21, and Table 3 has 14 out of 17. In Table 4, there are 16 items in total in the questionnaire list, but 11 items out of this range have the mean scores over 3. The key word he in Table 5 includes 18 items out of 28, and the keyword junzi consists of almost all items except item 29, 30, and 31.

However, because the definitions in the questionnaire have been used by different scholars or lexicographers as indicated in the section of research methods, it seems to be more interesting to notice the items that could not be agreed as key elements to explain the concept of the keyword. In other words, it is worthwhile mentioning that several conventional terms used among the literature and dictionaries were not agreed by the subjects involved in this study.

For the word ren (Table 1), the subjects were not familiar with the definitional element such as ‘benevolence’ (item 18) or ‘perfect virtue’ (item 20). In Table 2, ‘ceremony’ (item 15) and ‘rite’ (item 21) are not included for the word li. As for the word xiao (Table 3), the common translation ‘filial piety’ (item 16) is surprisingly excluded. And ‘character’ (item 14), ‘humanity’ (item 15) and ‘filial piety’ (item 16 in Table 4), are not part of de’s meanings.

In Table 5, more typical translations for the word he such as ‘concession’ (item 22), ‘affable’ (item 23), ‘concord’ (item 24), ‘eclectic’ (item 26), ‘capable of yielding’ (item 27) were not selected by these subjects.

Finally, according to the responses in Table 6, the word junzi does not refer to people ‘who are not disposed to quarrel with those in authority’ (item 29), ‘who won’t talk too much’ (item 30), or ‘who are affectionate but not partisan’ (item 31). Although many of these items are closer to 3 (see, also ‘ceremony’ in Table 2, ‘filial piety’ in Table 3), which may mean the neutrality of the overall responses, the results tend to appear towards the “disagreement” side of line (see above for the coding system). In fact, these two terms are often seen as a dictionary definition, but the results show that the subjects did not tend to agree with these terms.

On the other hand, although many items that show stronger agreement of the responses, (i.e. mean score above 3), their standard deviations show wider spread, (i.e. above 1.30, for example). This may mean that the respondents’ opinions might be quite different from one to another. The majority of the items comparatively show greater diversity of opinions as the results of the study reveal. In Table 2, ‘courtesy’ (item 9) and ‘etiquette’ (item 13) are the items with widespread standard deviations. It is also interesting to note that in Table 3 ‘obedience’ (item 8) and ‘respect of hierarchy’ (item 9) arouse the most varied opinions among the subjects. Moreover, in Table 6 ‘sincerity’ (item 21) and ‘obedience’ (item 24) have the mean scores nearly 3.5 to show that the overall responses have the tendency to include these two elements when explaining the keyword junzi. But again some subjects did not agree to use them to explain junzi according to their highest standard deviations, i.e. 1.33 and 1.31 respectively.

Results presented so far offer some space for further discussion. Because all translations were taken out of the translations and definitions used by various scholars and lexicographers as mentioned in the beginning of the paper, presumably all selected translations were able to explain the Chinese keywords. Based on this premise, the overall results may offer two major aspects of interpretation.

On the one hand, the findings may show that the respondents of the study did not pick up some common English equivalents of the Chinese cultural lexis possibly because these English translations consist of the keywords which are not part of their mental lexicon. In other words, it seems likely that some English translations or explanations are not included in the vocabulary list of high frequency words when learners of English may encounter. For example, ‘benevolence’ (item 18 in Table 1) for the keyword ren, or ‘affable’ (item 23 in Table 5) for he are not on the top of the 3000 word-list in the well-known Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (2003). Therefore, although the mean scores of the two English words are closer to 3, the tendency of the responses is still towards the “disagreement” side of line. In a word, translations in English, therefore, may be beyond their current vocabulary level so they could not agree with these terms when they filled in the questionnaire. But it would be interesting to confirm in the future development of the research if this justification is only a matter of disagreement or lack of vocabulary competence. This can be done in the future with one more option in the questionnaire stating that “I don’t know about the item because of the unknown words in it”.

On the other hand, although some English translations may seem to be agreed as the explanations for the Chinese target words (i.e. with the mean scores higher than 3), some respondents may disagree about the connotative values of the translations, such as ‘obedience’ (item 8) and ‘respect of hierarchy’ (item 9) for the keyword xiao in Table 3, and ‘sincerity’ (item 21) and ‘obedience’ (item 24) for junzi (cf. Table 6). However, agreement to or rejection of word meanings will need further research design to explore subjects’ “idiolects” or idiosyncrasies (Saeed, 2003, p. 6).

To summarize, the overall results have shown that the selected subjects would agree that many English definitional elements listed in the questionnaire can be used to explain a set of Chinese cultural lexis in Confucianism, but they did not select very conventional translations used by scholars, Sinologists, and lexicographers. In a word, this exploratory study has detected the fact that they did not agree with every of the pre-selected translations. But this has to be interpreted with some caution due to the two possibilities, i.e. either the majority of the subjects did not simply agree with these translations as good ones or they did not know some of the English translations.

This paper has indicated that explaining Confucian keywords in English is highly complex and has a cross-cultural concern. It presented an exploratory attempt to identify Taiwanese university students’ opinions of the selected English translations which have been used to describe Confucian keywords. The results have shown that some ‘common’ and ‘existing’ translations do not seem to be agreed to form part of the keywords’ meanings. It is possible that when filling in the questionnaire, the subjects might encounter unknown words in some translations so they could not indicate that they agree with the definitions and translations. Even if they knew every single word of the questionnaire items, they possibly did not agree with their traditional connotations of some translations or they did not think some translations and definitions are appropriate.

Although the materials and methods used in the study might be arguably in their preliminary development, additional research designs may be required to confirm the current findings. First, regarding the complexity of the subjects’ agreement or disagreement of the translations, it may be necessary to further provide information on subjects’ vocabulary competence (i.e. advance-level and low-level of students) and personal background information (i.e. age, the place of living, etc.) Second, in the present study the researcher had handpicked definitional elements of the six keywords through few of the representative works published both in the East and West in order to establish a list of translations used in various contexts, but the whole research process was time-consuming even when only six keywords were studied. In the meantime, it may be debatable about the extent to which the selected definitions in the questionnaire may be essential and demarcating elements. Thus it would save time and increase validity of research design if a corpus linguistic approach is employed to select definitional elements in a corpus of Confucianism. For example, the future development of the research can get access to the internet to download the full text of Confucius’ Lun Yu written in both Chinese and English (see, e.g. http://www.confucius.org/main01.htm). Ideally, the frequency count of the translations and of the overlaps of the definitional elements may be easily shown in future research. Third, different methods of analyzing the data, such as inferential statistics, can be conducted to give insights into the reliability and probability of the responses.

However, if this paper may raise more of questions regarding its place in using translation as an exercise in class, and understanding cultures through their keywords, then the contribution of the exploratory study seems to be multifaceted in the practice of EFL. In particular, there are three concrete implications directly for EFL learners in Taiwan. First, the study may serve as a start for them to sense that it is important to know Confucianism in English due to its rich discussions not only in the East but also in the West, and not only in Chinese language, but also in English. Second, there is complexity when the Confucian keywords or concepts need to be explained in English because there are different definitional elements. Students may recognize their translations in various contexts, and to negotiate the appropriateness of translating and explaining them in English. Third, as mentioned in this paper, course books designed by international publishers normally do not include the lesson of learning how to use English as an L2 to explain key cultural words of Chinese. Studying the Confucian keywords may serve as supplementary materials not only to raise their students’ L1 cultural awareness in EFL classroom (e.g. Lin, 2003), but also enlarge learners’ vocabulary size.

Despite the fact that the research study only focused on the investigation of some Chinese keywords of Confucianism, the above pedagogic suggestions may be equally applicable to other zones of teaching English as an L2 where cultural keywords of other cultural facets can be analyzed, taught and learned through English. In a word, teachers outside of Taiwan can be a researcher to study and analyze their own or students’ cultural keywords, so such information can be used in their particular teaching contexts.

Active Study Chinese-English Dictionary (ASCED). (1990). Taipei: Lanbridge Press.

Berthrong, J. H., & Berthrong, E. N. (2000). Confucianism: A short introduction. Oxford: Oneworld.

Byram, M., & Esarte-Sarries, V. (1991). Investigating cultural studies in foreign language teaching. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Chappell, H. (1994). Mandarin semantic primitives. In C. Goddard & A. Wierzbicka (Ed.), Semantical and Lexical Universal: Theory and Empirical Findings (pp. 109-147). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary (CECCED). (1986). Hong Kong: Oxford University Press and The Commercial Press.

Cortazzi, M., & Shen, W. W. (2001). Cross-linguistic awareness of key cultural lexis: a study of Chinese and English speakers. Language Awareness, 10 (2 & 3), 125-142.

De Mente, B. L. (1996). NTC’s Dictionary of China’s cultural code words. Illinois: NTC Publishing Group.

Gao, G., & Ting-Toomey, S. (1998). Communicating effectively with the Chinese. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Giles, H. A. (1984). San Zi Jing: Elementary Chinese. Taipei: Confucius Publishing.

Goddard, C. (1997). Cultural values and ‘cultural scripts’ of Malay (Bahasa Melayu). Journal of Pragmatics, 27, 183-201.

Goddard, C. (1998). Semantic analysis: A practical introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goddard, C. (1999). Cultural semantics and intercultural communication. Paper presented to the 4th Cross-Cultural Capability Conference at Leeds Metropolitan University, Leeds, UK.

Goddard, C., & Wierzbicka, A. (Ed.). (1994). Semantical and lexical universal: Theory and empirical findings. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Goddard, C., & Wierzbicka, A. (1997). Discourse and culture. In T. A. van Dijk (Ed.), Discourse as social interaction (pp. 231-257). London: Sage.

Hall, D. L., & Ames, R. T. (1987). Thinking through Confucius. New York: State University of New York Press.

Hall, J. K. (2002). Teaching and researching language and culture. Essex: Pearson Education Limited.

Hatch, E., & Brown, C. (1995). Vocabulary, semantics, and language education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harklau, L. (1999). Representing culture in the ESL writing classroom. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Culture in second language teaching and learning (pp. 109-130). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hinkel, E. (Ed.). (1999) Culture in second language teaching and learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hsu, F. (1971). Filial piety in Japan and China. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 2, 67-74.

Huang, C. (1997). The Analects of Confucius (Lun Yu). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Koller, J. M. (1985). Oriental philosophies. New York: Macmillan.

Ku, H. M. (1984). English translation of the Analects. Taipei: The Shin Sheng Daily News.

Lau, D. C. (1979). Confucius: The Analects (Lun Yu). London: Penguin.

Legge, J. (1980). English translation of the Four Books. Taipei: Culture Book.

Li, P. E. (Ed.). (1997). 1000 Characters. Singapore: SNP Publishing.

Lin, H. T. (2003). [Learning English through the Analects of Confucius]. Taipei: Cite.

Liu, W. C. (1955). A short history of Confucian philosophy. London: Penguin.

Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (LDOCE) (7th Ed). (2003). Essex: Longman.

Moore, C. (Ed.). (1967). The Chinese mind: Essentials of Chinese philosophy and culture. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Myers, D. (1996a). Strategic waiting in China: An ethnosemantic approach. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 7(3 & 4), 91-105.

Myers, D. (1996b). Studying words that teach culture. IRAL, 34(3), 199-214.

Read, J. (1997). Vocabulary and testing. In N. Schmitt & M. McCarthy (Eds.), Vocabulary: Description, acquisition and pedagogy (pp. 303-320). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Read, J. (2000). Assessing vocabulary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Saeed, J. I. (2003). Semantics. Oxford: Blackwell.

Shen, W. W. (2001). The vocabulary learning strategies of Chinese and British university students, with an analysis of approaches to selected cultural keywords. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Leicester, U.K.

Shen, W. W. (2007). Understand Chinese culture through its keywords. In B. Beaven (Ed.), IATEFL 2006: Harrogate conference selections (pp. 228-230). Kent: IATEFL.

Shi, C. (1987). Best books for Chinese children: A Chinese primer (1000 Characters). Taipei: Confucius Press.

Smith, D. H. (1985). Confucius and Confucianism. London: Paladin.

Smith, R. J. (1983). China’s cultural heritage: The Ch’ing Dynasty, 1644-1912. London: Francis Pinter Publishers.

The Pinyin Chinese-English Dictionary (TPCED). (1985). Beijing: The Commercial Press.

Waley, A. (1988). The Analects of Confucius. London: Unwin Hyman.

Wierzbicka, A. (1985). A semantic metalanguage for a crosscultural comparison of speech acts and speech genres. Language in Society, 14, 491-514.

Wierzbicka, A. (1991). Japanese keywords and core cultural values. Language in Society, 20, 333-385.

Wierzbicka, A. (1992a). Semantics, culture, and cognition: Universal human concepts in culture-specific configurations. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wierzbicka, A. (1992b). The search for universal semantic primitives. In R. Dirven & M. Pütz (Eds.), Thirty years of linguistic evolution (pp. 215-242). Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Wierzbicka, A. (1996). Contrastive sociolinguistics and the theory of “cultural scripts”: Chinese vs. English. In M. Hellinger & A. Ulrich (Eds.), Contrastive sociolinguistics (pp. 313-344). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Wierzbicka, A. (1997). Understanding cultures through their key words: English, Russian, Polish, German, and Japanese. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wierzbicka, A. (2001). What did Jesus mean?: Explaining the sermon on the mount and the parables in simple and universal human concepts. New York: Oxford University Press.

Willems, G. M. (Ed.). (1996). Issues in cross-cultural communication: The European dimension in language teaching. Netherlands: Hogeschool Gelderland Press Nijmegen.

Xu, C. (Ed.). (1990). The Three Character Classic in picture. Singapore: EPB Publishing.

Xu, H. (Eds.). (1994). San Zi Jing. Beijing: Huaxia.

Yao, X. (2000) An introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

The From Teaching to Training course can be viewed here

|